Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Moderator: Community Manager

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Hi all!

After over three years of strategically placing references, here's the finished product (Part one of three, anyway):

The Empire of Mexico, extended version

A. Part I – The early days to the end of the Tegetthoff era

1. Dictator for Life

After the disastrous war of 1846, Mexico lost huge territories, most importantly California, to the USA. This time, Mexican C-in-C General Santa Ana, who previously again and again had been able to repair his reputation even after the most humiliating reverses, seemed finished. He was exiled, but his successors created such chaos in short time that he was called back to restore order and had himself triumphantly elected president for the eleventh time on April 20th, 1853. Having grown ever more vainglorious as well as paranoid over the years, Santa Ana went about to establish a totalitarian dictatorship, only alleviated by a measure of corruption which was appalling even by Mexican standards. A conspiracy to oust him sprang into life almost immediately; to make sure he would not wiggle free as he had done so many times before, Santa Ana was to be assassinated this time. This decision was hotly debated and rejected by some of the conspirators, particularly Benito Juarez and Juan Ceballos, both lawyers by training, who wanted to play things straight. The military fraction, led by Ignacio Comonfort, wanted to play things safe and overruled them. Unfortunately, Ceballos suffered a case of conscience and confronted Santa Ana, demanding him to retire and go into exile, or else Ceballos would no longer be able to control the things to come. Santa Ana, far from being grateful, had Ceballos arrested and tortured, and within hours knew everything of the conspiracy. Swiftly and decisively, he cracked down on the conspirators and had several hundred of them, including Juarez, arrested and brutally executed during four bloody weeks late in 1854. The resistance was taken aback; they knew Santa Ana was ruthless and cruel, but had not believed he could be that efficient. Comonfort escaped and went underground, but he and his remaining supporters were relentlessly hunted. After two years of insurgence, the General was captured and publicly hanged; about 5.000 of his followers were massacred. Not content with this success and driven by clinical paranoia, Santa Ana continued to crack down on the country’s liberal bourgeoisie, aided by the army and the Catholic Church. He kept searching for conspiracies and had several of his own high-ranking police officers imprisoned for not finding any. Consequently, their successors made them up and pursued innocents to placate the irascible dictator. So wantonly violent was his regime that most of his conservative followers within the nobility, the land-owning class, the church and the military had abandoned him by 1860. Not content with turning every potential domestic ally against him, Santa Ana also upset his foreign debtors by defaulting upon them in 1861; he owed over 80 million dollars to the French Second Empire alone. This was one step too far for His Most Serene Highness, and Napoleon III had a plan drawn up to take over affairs in Mexico himself.

2. All hail the Emperor

Prior to 1861, direct intervention by any European power in Mexico would automatically have meant war with the USA, but when the American Civil War broke out in 1861, the Americans were occupied with more important matters. A few months into the American Civil War, in February 1862, French troops disembarked at Veracruz, bringing with them a descendant of the dynasty that had, as their propaganda claimed, brought civilization and Christianity to the Americas: Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg-Lorraine, younger brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. Moderate Mexican Conservatives fed up with Santa Ana's pompous, brutal dictatorship had approached the Archduke as early as 1859 to take over the country in a benevolent (for them, anyway) conservative revolution, but at that time Austria was at war with France and Ferdinand Maximilian was unable to muster the necessary financial and military support. The Archduke served in this war as C-in-C of the Austrian Navy; he was already considered an accomplished naval expert despite his young age and was credited with much of the organizational effort that created the Austrian fleet with which Tegetthoff won his victory at Lissa against Italy in 1866. Although the French had been his enemies in 1859, Ferdinand Maximilian quickly reconciled with Napoleon III as soon as his ascent to the Throne of Mexico became a real possibility. As Austria had no assets to spare for a Mexican expedition, Ferdinand Maximilian and Napoleon III struck an alliance that would give the Archduke access to several thousand crack French troops well experienced in North African counterinsurgency warfare, which was considered not too different from Mexican conditions. In return, Napoleon told Maximilian that he owed Mexico’s foreign debt to Napoleon personally; paying it back was the only reason for his reign, and failure to do so swiftly and enthusiastically would result in Maximilian’s removal, as quickly as he was installed. When Maximilian reached Veracruz, formerly Santa Ana’s main stronghold, he expected a cold welcome, but the conservatives – which Santa Ana had alienated – and the liberals – which he had massacred – were so desperate they were willing to support any kind of change, as long as it was a change. Maximilian’s French army, ably led by the legendary General Achille Bazaine, pulverized Santa Ana's numerically superior, but poorly led forces in a series of engagements between Veracruz and Mexico City, hardly suffering any casualties except to disease. Santa Ana, now aged 66 and obviously at the end of his fight, was paralyzed with shock. He issued one holding order after another, but failed to support his garrisons with the substantial reserves still available, concentrating his best units around Mexico City. His officer corps quickly came to realize that their dictator for life was a spent force. Three weeks after Maximilian had disembarked, the first dozen high-ranking officers switched sides, and within three months, most of the Mexican Army was either dispersed or had joined the invaders. When Santa Ana realized his army had simply vaporized, he tried to escape, but was caught on the run by soldiers under the command of rebel General Meja, beaten to death and hanged upside down from the roof of a stable. The demise of the universally hated dictator provided the Archduke, who spoke only a caricature of Spanish and still was considered by common Mexicans as the foreign invader he really was, with an air of legitimacy. The Mexican liberals had been thoroughly decapitated by Santa Ana's purges, and although they opposed monarchy as a matter of principle, their resistance was disorganized and ineffective. The Archduke was declared Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico in September 1862. To their lasting horror, his conservative supporters soon had to realize that they had gotten a very different Head of State than they had bargained for.

3. Cutting the strings

Whoever among Mexico's conservative elite considered Maximilian a docile figurehead under whose rule the upper class could continue to effortlessly plunder the country, should better have asked his brother Franz Joseph, who had sacked him as viceroy of Lombardo-Venetia in 1859 for his embarrassingly liberal views and policies. With a much larger experimenting ground for his liberal ideas available to him than North-eastern Italy had been, Maximilian proceeded to reform the country on the fast track. Many of his reforms were taken straight from the programme of the 1854 conspirators: Abolition of slavery and peony, land reforms, religious freedom, freedom of speech, abolition of corporal punishment, independent judiciary and the sovereignty of congress over the state’s budget. Social reforms included restricting working hours, the abolition of child labor, restoration of communal property and cancellation of all debts for peasants over 10 pesos. The near absolute rule of major land owners over the tenants of their estates was broken, and the whole legal system revamped after contemporary French fashion; for the first time, there were reliable and reasonably impartial courts in Mexico. Schooling was made to be made available to much larger parts of the general population, and suffrage was extended to all taxpayers, even those who actually worked for their income. Whatever liberal resistance against the emperor was still afoot steadily lost public support, and when the conservatives became restless they were made aware in diplomatic terms that Bazaine's French bayonets cut both ways. Maximilian would have Mexico become a modern nation, whether it wanted to be one or not; as such a nation was more likely to pay its debts than a third-world dunghole, Napoleon III agreed to defer payment of Mexican debts for five years in order to give Maximilian time to firmly take hold of his empire. Mexico’s nobility and clergy felt thoroughly betrayed. Maximilian did just what Juarez would have done, had he defeated Santa Ana – so what use was that weird prince, anyway? A new conspiracy to get rid of the Emperor sprang up in 1864, but indigenous army units refused to move against the man who had recently doubled their wages and abolished whipping; after General Miramon had declared for Maximilian and spilled what he knew of the conspiracy, loyal troops under the native American General Meija killed the coup attempt in its cradle early in 1865. Many prominent reactionaries were arrested, to the delight of Mexico's liberal bourgeoisie which now started to believe this Emperor might be a godsend after all. By year’s end, more and more formerly staunch Juaristas were flocking to the banners of Emperador Maximiliano, glorious liberator of Mexico from the claws of Santa Ana.

4. Crisis

Just when all was going well, Maximilian's brother Emperor Franz Josef was defeated by the Prussians with humiliating ease in the German war of 1866. As the victorious Prussians turned their attention west at the arch-enemy beyond the Rhine, the USA, after having finished the civil war, started to exert diplomatic pressure on the French to get the hell out of the Americas. The Johnson administration did not believe for a second in the tale of a sovereign Mexican Empire; to them, the whole endeavor was aimed at turning Mexico into a French colony. By mid-1867, under pressure from two sides, Napoleon III decided he would need his 40.000 crack troops, which still bolstered Maximilian's reign in Mexico, more urgently at home. The French retreat was completed late in 1867. As the French drew their troops out, the first groups of Confederate veterans, many of which would have returned to a life of misery in their devastated home states, started to cross the Rio Grande. These men had little chance of earning a decent living in the postwar South; they did however know how to fight. They had been told there was a civil war brewing, with all associated opportunities for plunder, loot and debauchery, and wanted to be on the winning side for once. The US government was happy to be rid of them; if they destabilized the Mexican Empire instead of destabilizing the South, it was a win-win situation. In Mexico, the Confederate veterans arrived in a climate of insurgence against the Empire. What remained of the conservative elite, recently decimated by Maximilian, and the radical liberals, previously decimated by Santa Ana, took up arms at the same time. With the Empire thus caught in a pincer grip, there could be little doubt for the ex-Confederates who the winning side would be. But at the same time, the middle ground between both extreme camps – which in Mexico was traditionally a rather small strip – had grown much wider since Maximilian’s arrival, and the rebel camps hated each other at least as much as they hated the Empire. Maximilian's indigenous army had been trained well by French advisors in counterinsurgency tactics, about which the French had gathered some experience in their North African campaigns. Some French officers had opted to stay behind, baited by generous promotions, and Maximilian had imported a number of artillery and logistics experts from Austria. But for all the progress that had been made with the officer corps, the rank and file still were of questionable efficiency, so the Emperor refused to unleash his fledgling army piecemeal and prematurely. The strict discipline enforced upon the Imperial army and the draconic measures threatened in case of marauding scared off the worst of the ex-Confederates straight to the conservative rebels, who lacked unified leadership, usually took anyone they could get, and promised rewards they could not deliver. Maximilian’s generals were happy to let them. Miramon and Meija wanted to fight the upcoming civil war with Mexicans; employing a large number of Gringo mercenaries would only undermine the Emperor’s fledgling popularity. While various rebel groups and bands of freelance ex-Confederates ravaged the country, Maximilian concentrated his forces in their strongholds. It seemed the same mistake Santa Ana had made, but Maximilian's forces were of better quality and cohesion, and his generals used the time gained to relentlessly drill them. By early 1868, the Empire struck, prioritizing the more visible conservative and reactionary rebels. They had to fight the leftists and the Imperials at the same time and could be virtually crippled during the spring of 1868. The Imperial victory rendered the leftists stronger as well, to whom the Confederate veterans quickly defected. This perceived position of strength would however be their undoing. Used to traditional warfare between organized armies, the ex-Confederates habitually overreacted to asymmetric threats, and caused more collateral damage and friendly fire casualties than actual harm to the enemy. Their frequently excessive brutality sapped public support from the cause of the rebels. Moreover, the ex-Confederates held the Imperial army in such contempt that they pushed their respective leaderships for a major offensive; surely Maximilian's ill-trained rabble would be a walkover for the men who had marched with General Lee. During the summer of 1868, various leftist groups consolidated their forces and moved to capture several large cities in northern Mexico, clandestinely supplied with weapons from beyond the Rio Grande, courtesy of General Sheridan. Maximilian could hardly believe his luck: The rebels, who would have been unassailable as long as they stayed dispersed, were together and in the open. Although General Miramon had never distinguished himself as much of a tactician before, he decisively defeated the rebels during the fall of 1868, and imperial propaganda was able to play the frequent inability (or unwillingness) of Confederate veterans to discriminate friends from enemies for all it was worth. By late 1868, US weapons supplies to the rebels had been uncovered, and a majority of Mexicans viewed the 1867 rebellion against the Empire as a foreign invasion staged by bloodthirsty, greedy Gringo adventurers. This was the end for the rebellion. Many rebel leaders including Porfirio Diaz were captured and executed in the spring of 1869. Small scale insurgence continued into 1870, but by that time, Emperor Maximilian’s rule was for all practical purposes stabilized and there to stay. In 1871, he gained financial freedom of action by renouncing his debts to France. Napoleon III had made it a personal issue to threaten Maximilian, but with Napoleon deposed and France a republic, Maximilian argued the creditor – the Second French Empire – had vanished in a legal sense, so the deal was off. The French were so busy with the war and the Commune that they hardly noticed; when the Third Republic was consolidated in 1872, there was no way to force the Mexicans to pay up short of war. This however was a no-go, with France’s army crippled and the USA, however they despised the Mexican monarchy, again able and willing to impose the Monroe doctrine to prevent a repetition of France’s 1863 adventure. The matter soured French-Mexican relations for a decade, but Germany and Austria happily stepped in as creditors (the latter for dynastic solidarity, the former to piss off the French), and Mexico’s credit ranking did not suffer. For Maximilian, it was a diplomatic triumph which massively boosted his popularity; there could be no doubt now that he was no one’s puppet. All that was missing to round the picture was a heir, which was no easy undertaking, because Maximilian was widely considered to be impotent due to the effects of veneral disease. When he surprised everyone by declaring the Empress pregnant in 1872, rumors abounded about the child's true fatherhood. These were however short-lived when the imperial pregnancy went awry and the Empress died giving birth to a girl so ugly that any doubts about Maximilian's fatherhood could be discounted. The Infanta received the name Isabel Carlota Sofia Maria Teresa de Habsburgo-Lorena. The Emperor celebrated his grief very publicly, which appealed to the Mexican flair for tragic romance, ironically further enhancing his popularity. Bereft of family (he would never remarry, although continue to have affairs with numerous mistresses), the Emperor decided to distract himself by doing what he had already proven very capable of: He created himself a navy.

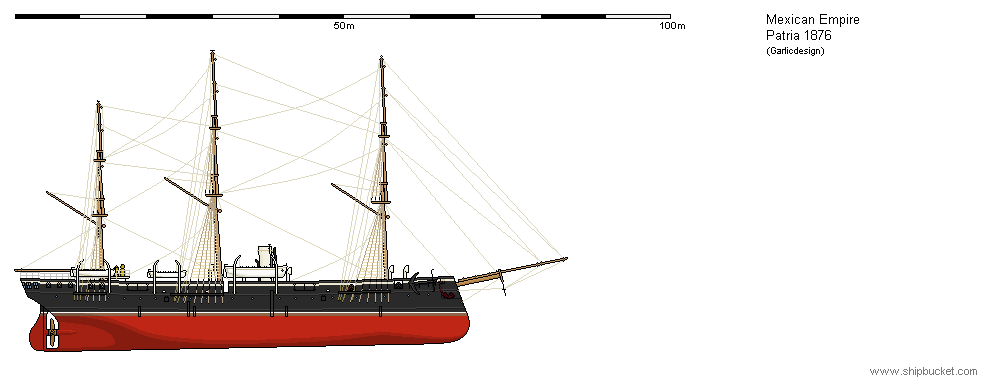

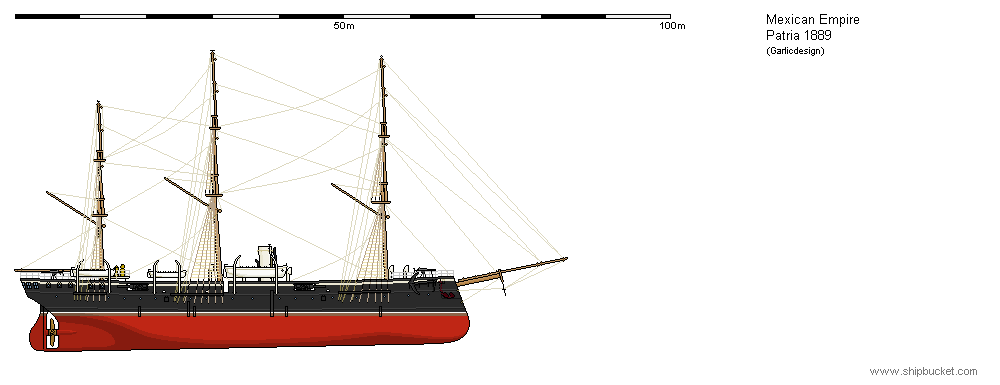

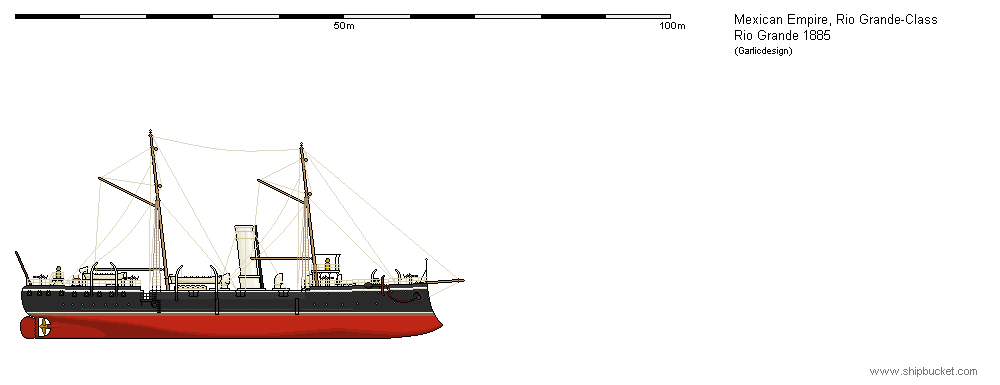

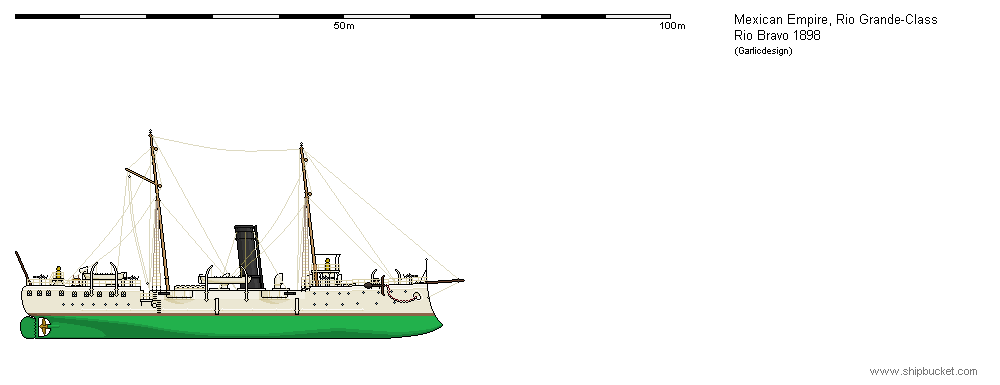

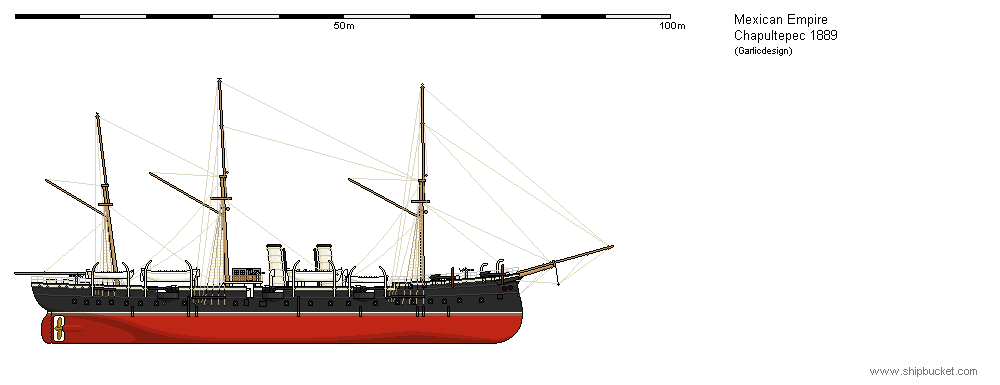

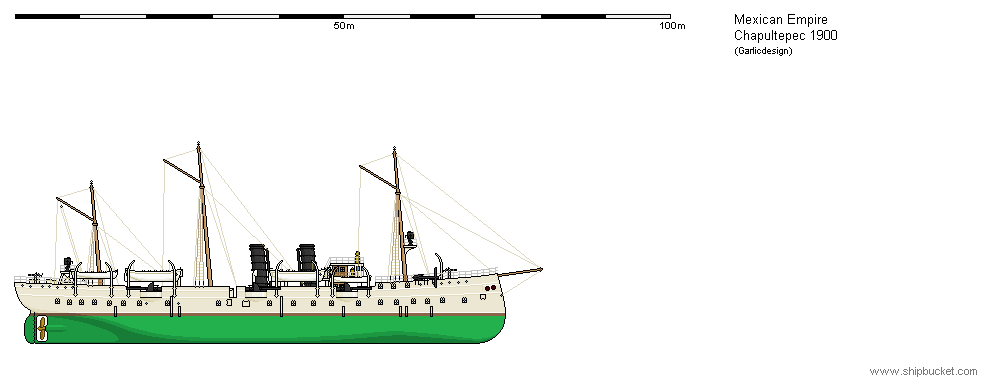

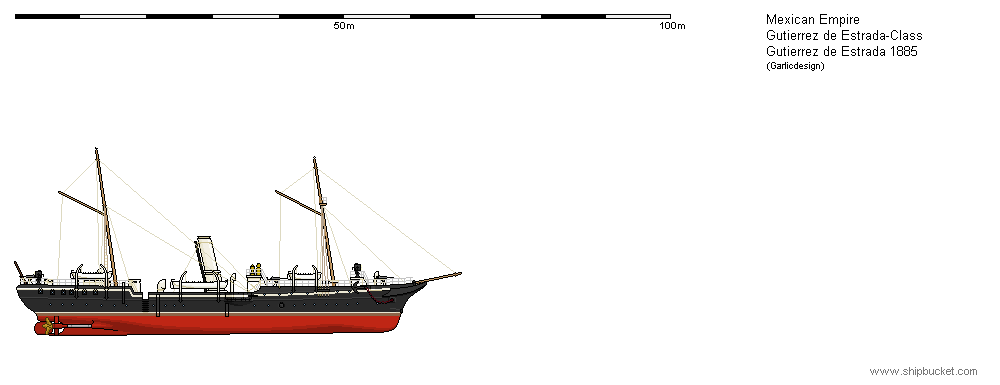

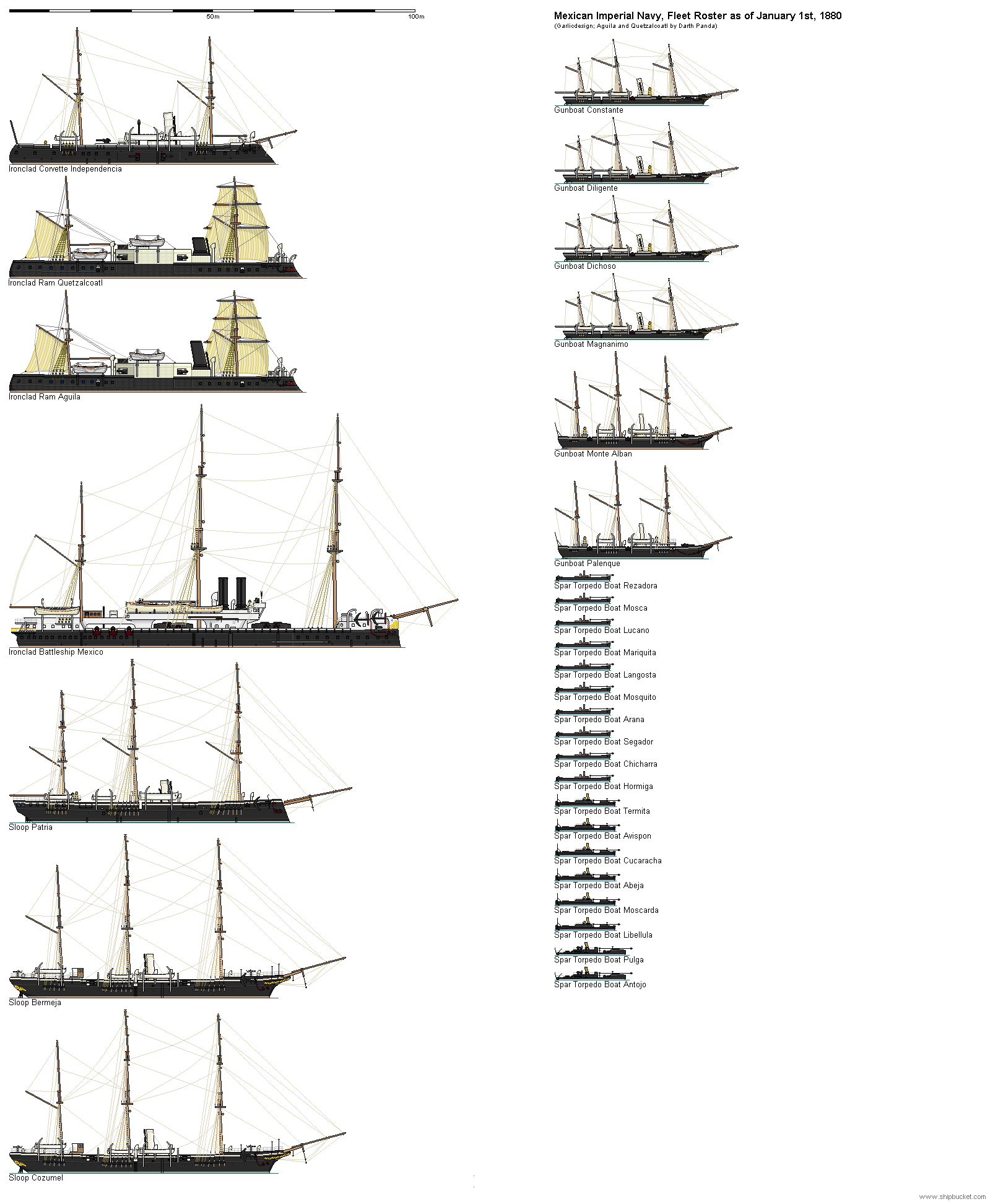

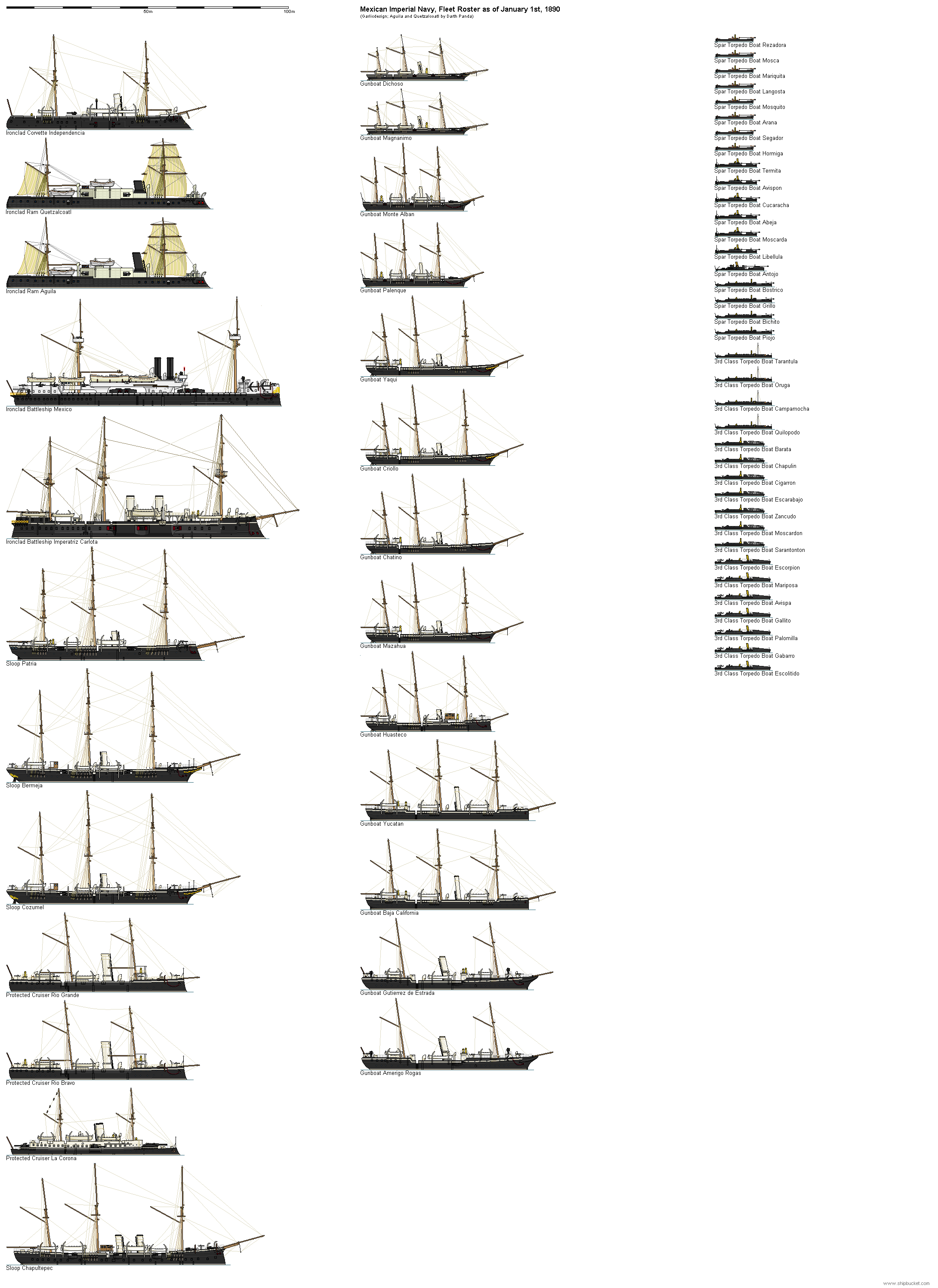

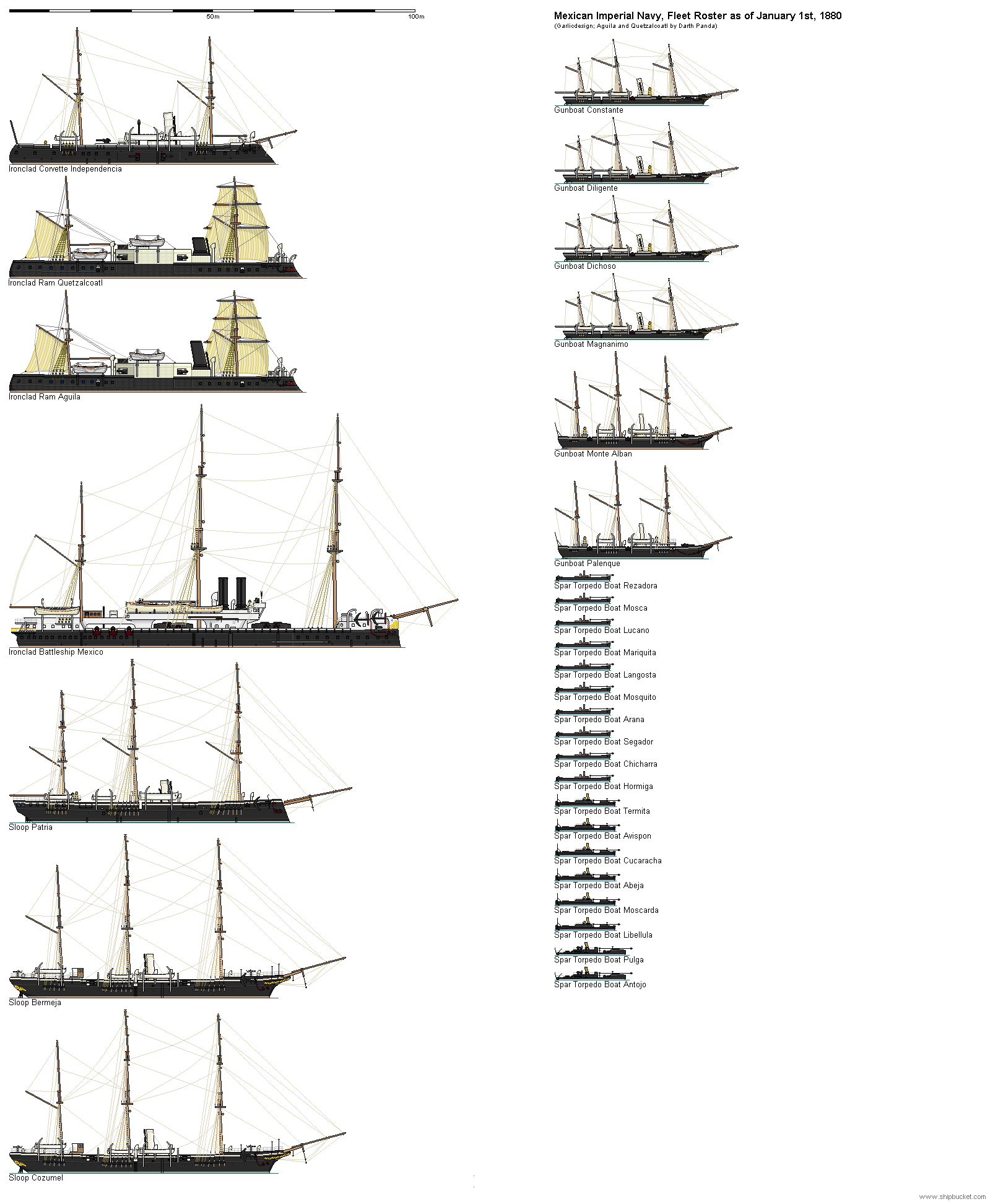

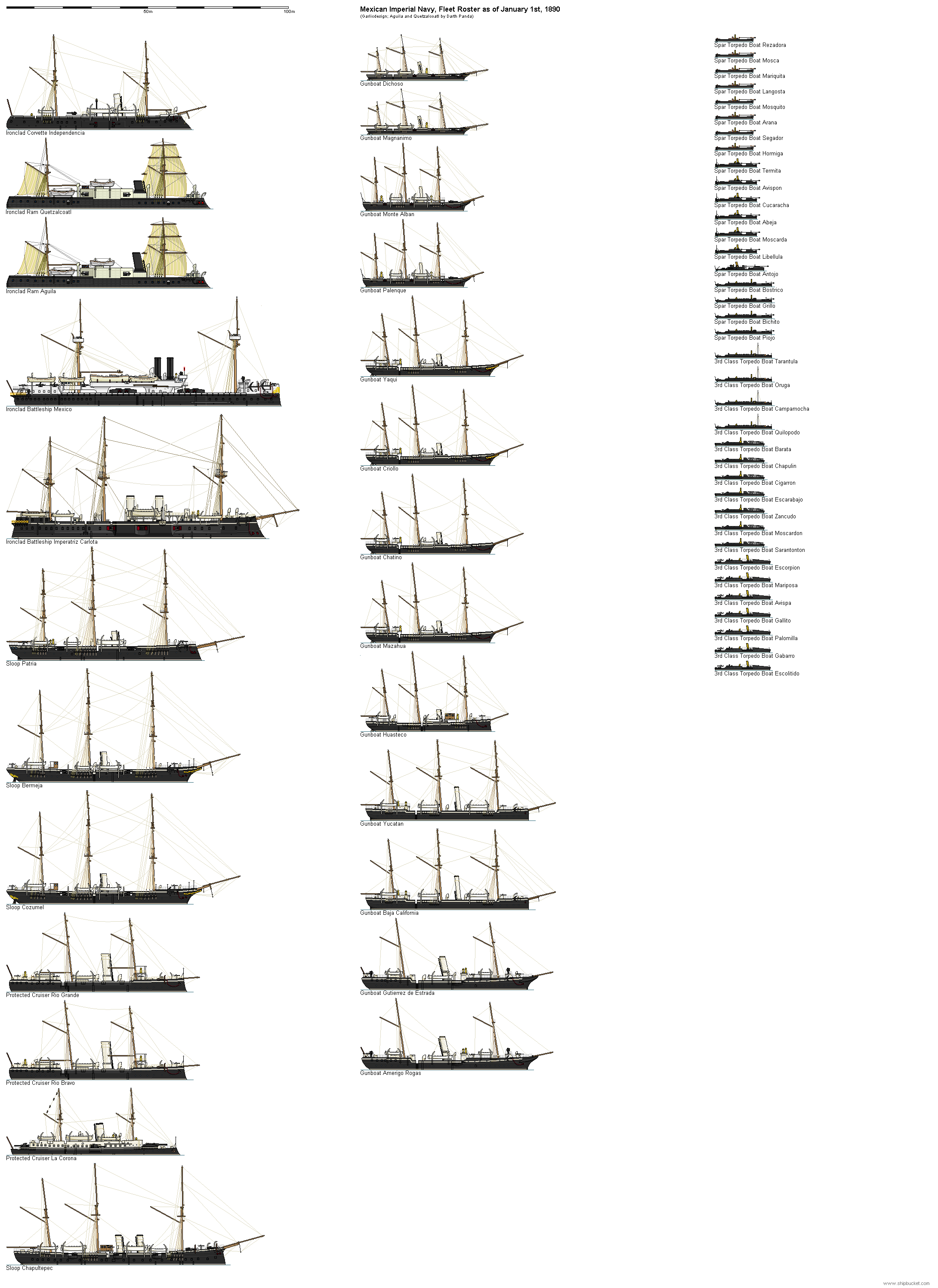

5. The Emperor's Admiral

Mexico had possessed no naval forces worth mentioning when Maximilian arrived; whatever steam warships had been available, Santa Ana had sold to the Spanish to finance the 1854 civil war, leaving only a handful of decrepit sailing ships. Maximilian had already purchased four British-built wooden steam schooners in 1866 and an Austrian-built wooden steam sloop in 1868; in 1872, he added a small ironclad and two more steam sloops from Austrian manufacture, and three more British built masted steam gunboats. This was however only the beginning. Maximilian’s ambition was to turn Mexico into a self-sustained naval power with a professional officer corps of the highest quality and the ability to build every kind of warship domestically. To that end, Maximilian managed to secure the assistance of one of the premier mariners of the century. After his victory at Lissa, Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff never had it easy with the Austrian bureaucracy. He had almost resigned in that year after the imperial administration had accused him of fraud because of the size of his victory dinner (little wonder there; his victory had not prevented the Austrians from losing the war). His resignation was refused, but the KuK administration's ongoing effort to undermine his work - he was viewed as the proverbial crab trying to climb out of the bucket which needed to be drawn down to the general level of complacency, inefficiency and corruption - strained his health and his nerves. Fortunately for him, the latter gave way before the former, and he resigned his position for a second time in September 1870 after a row with the government over its decision to limit the battlefleet to eight ironclads, while Tegetthoff wanted twenty. As he was in poor health at that time, one might fear that any continuation of the stress he was suffering might have killed him sooner rather than later. Tegetthoff decided to accept a long-standing invitation of his former C-in-C, Maximilian of Mexico, who had recognized Tegetthoff's talents very early during his tenure as head of the Austrian navy and rapidly promoted him. The admiral traveled to Mexico, where he arrived in December 1870 to a lavish welcome. During the following year, he recovered his health, mostly living on an imperial resort in the warm and dry climate of Baja California; in fall, he traveled the country, whose economy was beginning to flourish again, with the civil war for all practical purposes over. Tegetthoff, who already was fluent in Italian, easily picked up Spanish, and with his spirits and energy restored, he did not think twice when Maximilian offered him a job. On April 1st, 1872, Wilhelm von Tegetthoff was appointed Mexico's first-ever Minister of the Navy, receiving a promotion to full admiral (the next ranking Mexican naval officer at that time was a Captain) at age 45. The first thing Tegetthoff did was upgrading the extant bases at Veracruz and Acapulco, adding three more at Tampico in 1873, at Topolobampo in 1878 and at Chetumal in 1882. He founded a Naval Academy at Veracruz in 1873 and Naval Yards at Tampico in 1875 and at Veracruz in 1880. The yards were initially for maintenance only, but soon became more proficient and capable of turning out warships. Additionally, the Emperor applied various measures to attract foreign investment to initiate domestic iron ore mining and establish a Mexican steel industry; the latter venture never really took off, though. Foreign instructors – initially Austrian, later British and German - were employed to turn Mexico's fledgling officer and deck officer corps into a professional fighting force. This sort of groundwork had priority over the acquisition of new ships in the first years; between 1872 and 1878, only a handful of spar torpedo boats were purchased. That year however, Tegetthoff considered all foundations laid for a contemporary fleet, and started to buy. Gunboats were built in Mexico from the start; only a few prototypes were imported. Large or high-performance ships still needed to be built abroad, but there always was a focus on acquiring their plans and developing the capability to build domestic copies. In 1879, no less than four ironclads were purchased. One was newly built at Trieste to requirements formulated by Tegetthoff himself, the other three were bought from the British government which had acquired three former Turkish and Brazilian ships during the Russian War Scare of 1878, only to realize they had no real requirement for them. In the following decade, additional cruisers and torpedo gunboats were added to the fleet, and in 1885, the first Mexican-designed cruiser (at the same time the last iron warship built for the Imperial Navy) was laid down at Tampico. During this buildup, the performance of Mexican crews improved from farcial to adequate, and the first generation of home-grown professional officers was steadily improving their proficiency. This development was not without foreign political repercussions. The Americans had ignored Tegetthoff’s work for a long time; a 12-year period of neglect during the Grant and Hayes administrations reduced the Old Navy to near uselessness. The USA was busy with internal issues during that time, and it took them till 1885 to realize they had been outpaced by their despised southern neighbors. The USN still outnumbered the Mexican fleet, but virtually all American ships were obsolete, and the extant ironclads were all of the coastal or riverine type. In contrast, the Mexican ironclads Mexico and Imperatriz Carlota were the most powerful oceangoing warships in the Americas, with no equivalent in the USN; only the big Thiarian central citadel ironclads Conlan and Caithreim were remotely their equal. This realization was the alarm signal that prompted the Arthur administration to fundamentally renew the USN.

6. Spanish troubles

The year 1885 saw the first test for the fledgling Mexican fleet. When the Spanish king Alfonso XII suddenly died that year, progressive elements launched a poorly planned and ultimately botched coup d'etat against the regency of his widow Queen Maria Christina, who had yet to give birth to Alfonso's son, the future Alfonso XIII. Given her advanced state of pregnancy, the Queen - daughter of Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria and thus a cousin of Maximilian's - preferred to leave the country till things were sorted out, and boarded a ship for a spontaneous visit to her relative in Mexico. She made the mistake of using a Spanish-flagged ship, which was captured by rebel forces within sight of the Mexican base on Bermeja Island, and brought to Cuba. When Maximilian got wind of this outrage, he demanded his cousin’s release, and when the rebels did not react, he sent his fleet under Tegetthoff's personal command to Cuba. Tegetthoff, flying his flag on the Imperatriz Carlota (he got seasick on the more powerful, but rather too lively Mexico), engaged an inferior Spanish force consisting of a broadside ironclad, a floating battery and some gunboats in battle of Casimba. During this one-sided affair, the Mexican ironclad Aguila (Capt. Perez Valence) sank the Spanish ironclad Mendez Nunez, which became the last ever capital ship to be sunk on purpose by ramming. The small floating battery Duque de Tetuan was shot up and sunk by the Mexican flagship, and the Spanish gunboats fled as fast as they could steam. Tegetthoff then proceeded to blockade Santiago de Cuba, but soon after the battle of Casimba, the coup in Spain collapsed and the Queen Regent was released to return to Spain in triumph. This humiliation at the hands of a third-rate naval power - and a former colony to boot - triggered a vigorous Spanish reaction; a far-reaching programme to rebuild the run-down Spanish fleet was launched the year after, which resulted in the acquisition of six battleships and eight large cruisers, plus substantial light forces, over the next ten years. The Spaniards also began to fortify Guantanmo Bay for use as a naval base in a future conflict. Tegetthoff was styled Duque de Tampico upon his return; when he asked for a - by the standards of the time - outrageous sum of money for another large fleet building programme, it was granted without a second thought. Under the 1886 programme, Mexico’s first steel ironclad and two large protected cruisers were ordered in Austria, and three small cruisers from domestic yards; one of them was the first large warship built at the second naval yard at Tampico in 1890. The first four Austrian-built seagoing torpedo boats were acquired in 1888, and a big battleship – at 10.000 tons the largest in the Americas – was laid down at Trieste that same year. By that time, Tegetthoff, as much the creator of Mexico’s Navy as the Emperor himself, had already retired, aged 60; events however would force him to return two years later.

7. Clash with the Titan

The French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had overseen construction of the Suez channel in the 1870s, had to witness it fall into the hands of Great Britain, the old enemy of his native France, practically immediately upon completion. Undeterred, he proceeded to head an even more ambitious project in 1881 and started construction of a channel through the Isthmus of Panama. Technical difficulties and cost overruns resulted in the bankruptcy of his company in mid-1889, and he asked the French government to step in. When the Harrison administration in Washington got wind, they cited a violation of the Monroe doctrine and threatened with war if the French acquired such a crucial strategic position in Central America. Although the French navy at that time had 25 ironclads in commission and could have walked straight through the USN at half-power, France’s government, still careful after its defeat against Prussia in 1871, backed off. Emperor Maximilian figured the Monroe doctrine did not to apply to Mexico, being an American country after all, and in 1890 proposed to Lesseps and the Colombian government to step in, in exchange for control rights over the completed channel. President Harrison was outraged by this impertinence of some inbred Balkan Autocrat (original tone) and threatened Maximilian with the direst consequences if he proceeded on his course; Monroe doctrine or not, the USA would not tolerate anybody except themselves to acquire a channel across the Isthmus. In response to Harrison's intentionally insulting statement, Maximilian asked Tegetthoff to come out of retirement and lead his fleet on a foray across the Caribbean towards Key West to show his resolve and determination. President Harrison - warned in vain by his advisors that the USN's inventory was outdated and still had no oceangoing battleships at all – ordered his fleet, consisting of little more than four protected cruisers, an unprotected cruiser and three gunboats – to sea from Key West to face off the Mexicans. Simultaneously, he issued a part mobilization of the US Army and moved several crack units to Texas. Maximilian's military advisors now developed cold feet. Although the USA at that time was at the historical nadir of its military power, its sheer size – the USA had five times the population and ten times the economy of Mexico – justly convinced them that they could not win a full-scale war. Better to show force than to use it, Maximilian's advisors argued, and some solution favorable to Mexico might be obtained at the negotiating table. At that stage of deliberations, both fleets met about 50 miles southwest of Key West (Cayo Hueso) in the early morning of May 29th, 1890, in what was to become the eponymous battle. Tegetthoff, completely outnumbering the Americans with a fleet of four ironclads, two protected and two unprotected cruisers, plus four gunboats, decided that refusing to salute the US flag would be a fine way to show resolve and determination. This calculated insolence provoked a warning shot by USS Charleston, which quickly developed into a shootout, leaving three US protected cruisers damaged, the brand new USS Charleston quite severely, and the old USS Trenton afire and in a sinking condition, against minimal damage to the Mexican ships. The Americans then retreated to their base, leaving the Mexican fleet in control of the sea. When the news broke, the American public was flabberghasted and, after the initial shock had worn off, roared for revenge for what the press called an act of piracy on Tegetthoff's part. International voices were more benign; even the British, who had no sympathies for the Habsburg Empire and its Mexican seedling, were of the opinion that the US commander, Admiral Gherardi, who died of his wounds soon after return, had handled the incident poorly by not waiting for the US main force of four large monitors available at Key West. Although President Harrison knew that an US invasion in Mexico would cause more trouble than it was worth, he played his cards well and - by pretending he could not resist the internal pressure of the war party - scared the Mexicans into a negotiated settlement that gave the US everything they wanted. In the treaty of Tijuana, Maximilian had to forsake all ambitions in Panama, sack Tegetthoff and pay reparations for US losses in the ‘Battle’ of Cayo Hueso; despite such expense, the Mexicans could afford to order further modern warships under the 1890 emergency program. Tegetthoff and his second-in-command Rear Admiral Cordona were celebrated in Mexico City. After all, the first shot had been fired by the Americans, and they were considered the defenders of Mexico's honor. Cordona was made Minister of the Navy, and Tegetthoff, as a reactivated pensioner, could afford to graciously retire from his post, robbing the Americans of the satisfaction of having forced Maximilian to get rid of him. After the wave of hero worship, which he thoroughly enjoyed, had ebbed down, Tegetthoff embarked upon a journey to Austria in October 1890, where he got another round of it. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany dropped everything to meet him and is reported to have embarrassed himself by acting like a teenager in the presence of a pop star. But the most famous Admiral of the 19th century outside Great Britain would not get the time to enjoy his retirement. Acclimatized to Mexican weather, he promptly caught pneumonia in the following central European winter and died in April 1891, aged 64.

After over three years of strategically placing references, here's the finished product (Part one of three, anyway):

The Empire of Mexico, extended version

A. Part I – The early days to the end of the Tegetthoff era

1. Dictator for Life

After the disastrous war of 1846, Mexico lost huge territories, most importantly California, to the USA. This time, Mexican C-in-C General Santa Ana, who previously again and again had been able to repair his reputation even after the most humiliating reverses, seemed finished. He was exiled, but his successors created such chaos in short time that he was called back to restore order and had himself triumphantly elected president for the eleventh time on April 20th, 1853. Having grown ever more vainglorious as well as paranoid over the years, Santa Ana went about to establish a totalitarian dictatorship, only alleviated by a measure of corruption which was appalling even by Mexican standards. A conspiracy to oust him sprang into life almost immediately; to make sure he would not wiggle free as he had done so many times before, Santa Ana was to be assassinated this time. This decision was hotly debated and rejected by some of the conspirators, particularly Benito Juarez and Juan Ceballos, both lawyers by training, who wanted to play things straight. The military fraction, led by Ignacio Comonfort, wanted to play things safe and overruled them. Unfortunately, Ceballos suffered a case of conscience and confronted Santa Ana, demanding him to retire and go into exile, or else Ceballos would no longer be able to control the things to come. Santa Ana, far from being grateful, had Ceballos arrested and tortured, and within hours knew everything of the conspiracy. Swiftly and decisively, he cracked down on the conspirators and had several hundred of them, including Juarez, arrested and brutally executed during four bloody weeks late in 1854. The resistance was taken aback; they knew Santa Ana was ruthless and cruel, but had not believed he could be that efficient. Comonfort escaped and went underground, but he and his remaining supporters were relentlessly hunted. After two years of insurgence, the General was captured and publicly hanged; about 5.000 of his followers were massacred. Not content with this success and driven by clinical paranoia, Santa Ana continued to crack down on the country’s liberal bourgeoisie, aided by the army and the Catholic Church. He kept searching for conspiracies and had several of his own high-ranking police officers imprisoned for not finding any. Consequently, their successors made them up and pursued innocents to placate the irascible dictator. So wantonly violent was his regime that most of his conservative followers within the nobility, the land-owning class, the church and the military had abandoned him by 1860. Not content with turning every potential domestic ally against him, Santa Ana also upset his foreign debtors by defaulting upon them in 1861; he owed over 80 million dollars to the French Second Empire alone. This was one step too far for His Most Serene Highness, and Napoleon III had a plan drawn up to take over affairs in Mexico himself.

2. All hail the Emperor

Prior to 1861, direct intervention by any European power in Mexico would automatically have meant war with the USA, but when the American Civil War broke out in 1861, the Americans were occupied with more important matters. A few months into the American Civil War, in February 1862, French troops disembarked at Veracruz, bringing with them a descendant of the dynasty that had, as their propaganda claimed, brought civilization and Christianity to the Americas: Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg-Lorraine, younger brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. Moderate Mexican Conservatives fed up with Santa Ana's pompous, brutal dictatorship had approached the Archduke as early as 1859 to take over the country in a benevolent (for them, anyway) conservative revolution, but at that time Austria was at war with France and Ferdinand Maximilian was unable to muster the necessary financial and military support. The Archduke served in this war as C-in-C of the Austrian Navy; he was already considered an accomplished naval expert despite his young age and was credited with much of the organizational effort that created the Austrian fleet with which Tegetthoff won his victory at Lissa against Italy in 1866. Although the French had been his enemies in 1859, Ferdinand Maximilian quickly reconciled with Napoleon III as soon as his ascent to the Throne of Mexico became a real possibility. As Austria had no assets to spare for a Mexican expedition, Ferdinand Maximilian and Napoleon III struck an alliance that would give the Archduke access to several thousand crack French troops well experienced in North African counterinsurgency warfare, which was considered not too different from Mexican conditions. In return, Napoleon told Maximilian that he owed Mexico’s foreign debt to Napoleon personally; paying it back was the only reason for his reign, and failure to do so swiftly and enthusiastically would result in Maximilian’s removal, as quickly as he was installed. When Maximilian reached Veracruz, formerly Santa Ana’s main stronghold, he expected a cold welcome, but the conservatives – which Santa Ana had alienated – and the liberals – which he had massacred – were so desperate they were willing to support any kind of change, as long as it was a change. Maximilian’s French army, ably led by the legendary General Achille Bazaine, pulverized Santa Ana's numerically superior, but poorly led forces in a series of engagements between Veracruz and Mexico City, hardly suffering any casualties except to disease. Santa Ana, now aged 66 and obviously at the end of his fight, was paralyzed with shock. He issued one holding order after another, but failed to support his garrisons with the substantial reserves still available, concentrating his best units around Mexico City. His officer corps quickly came to realize that their dictator for life was a spent force. Three weeks after Maximilian had disembarked, the first dozen high-ranking officers switched sides, and within three months, most of the Mexican Army was either dispersed or had joined the invaders. When Santa Ana realized his army had simply vaporized, he tried to escape, but was caught on the run by soldiers under the command of rebel General Meja, beaten to death and hanged upside down from the roof of a stable. The demise of the universally hated dictator provided the Archduke, who spoke only a caricature of Spanish and still was considered by common Mexicans as the foreign invader he really was, with an air of legitimacy. The Mexican liberals had been thoroughly decapitated by Santa Ana's purges, and although they opposed monarchy as a matter of principle, their resistance was disorganized and ineffective. The Archduke was declared Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico in September 1862. To their lasting horror, his conservative supporters soon had to realize that they had gotten a very different Head of State than they had bargained for.

3. Cutting the strings

Whoever among Mexico's conservative elite considered Maximilian a docile figurehead under whose rule the upper class could continue to effortlessly plunder the country, should better have asked his brother Franz Joseph, who had sacked him as viceroy of Lombardo-Venetia in 1859 for his embarrassingly liberal views and policies. With a much larger experimenting ground for his liberal ideas available to him than North-eastern Italy had been, Maximilian proceeded to reform the country on the fast track. Many of his reforms were taken straight from the programme of the 1854 conspirators: Abolition of slavery and peony, land reforms, religious freedom, freedom of speech, abolition of corporal punishment, independent judiciary and the sovereignty of congress over the state’s budget. Social reforms included restricting working hours, the abolition of child labor, restoration of communal property and cancellation of all debts for peasants over 10 pesos. The near absolute rule of major land owners over the tenants of their estates was broken, and the whole legal system revamped after contemporary French fashion; for the first time, there were reliable and reasonably impartial courts in Mexico. Schooling was made to be made available to much larger parts of the general population, and suffrage was extended to all taxpayers, even those who actually worked for their income. Whatever liberal resistance against the emperor was still afoot steadily lost public support, and when the conservatives became restless they were made aware in diplomatic terms that Bazaine's French bayonets cut both ways. Maximilian would have Mexico become a modern nation, whether it wanted to be one or not; as such a nation was more likely to pay its debts than a third-world dunghole, Napoleon III agreed to defer payment of Mexican debts for five years in order to give Maximilian time to firmly take hold of his empire. Mexico’s nobility and clergy felt thoroughly betrayed. Maximilian did just what Juarez would have done, had he defeated Santa Ana – so what use was that weird prince, anyway? A new conspiracy to get rid of the Emperor sprang up in 1864, but indigenous army units refused to move against the man who had recently doubled their wages and abolished whipping; after General Miramon had declared for Maximilian and spilled what he knew of the conspiracy, loyal troops under the native American General Meija killed the coup attempt in its cradle early in 1865. Many prominent reactionaries were arrested, to the delight of Mexico's liberal bourgeoisie which now started to believe this Emperor might be a godsend after all. By year’s end, more and more formerly staunch Juaristas were flocking to the banners of Emperador Maximiliano, glorious liberator of Mexico from the claws of Santa Ana.

4. Crisis

Just when all was going well, Maximilian's brother Emperor Franz Josef was defeated by the Prussians with humiliating ease in the German war of 1866. As the victorious Prussians turned their attention west at the arch-enemy beyond the Rhine, the USA, after having finished the civil war, started to exert diplomatic pressure on the French to get the hell out of the Americas. The Johnson administration did not believe for a second in the tale of a sovereign Mexican Empire; to them, the whole endeavor was aimed at turning Mexico into a French colony. By mid-1867, under pressure from two sides, Napoleon III decided he would need his 40.000 crack troops, which still bolstered Maximilian's reign in Mexico, more urgently at home. The French retreat was completed late in 1867. As the French drew their troops out, the first groups of Confederate veterans, many of which would have returned to a life of misery in their devastated home states, started to cross the Rio Grande. These men had little chance of earning a decent living in the postwar South; they did however know how to fight. They had been told there was a civil war brewing, with all associated opportunities for plunder, loot and debauchery, and wanted to be on the winning side for once. The US government was happy to be rid of them; if they destabilized the Mexican Empire instead of destabilizing the South, it was a win-win situation. In Mexico, the Confederate veterans arrived in a climate of insurgence against the Empire. What remained of the conservative elite, recently decimated by Maximilian, and the radical liberals, previously decimated by Santa Ana, took up arms at the same time. With the Empire thus caught in a pincer grip, there could be little doubt for the ex-Confederates who the winning side would be. But at the same time, the middle ground between both extreme camps – which in Mexico was traditionally a rather small strip – had grown much wider since Maximilian’s arrival, and the rebel camps hated each other at least as much as they hated the Empire. Maximilian's indigenous army had been trained well by French advisors in counterinsurgency tactics, about which the French had gathered some experience in their North African campaigns. Some French officers had opted to stay behind, baited by generous promotions, and Maximilian had imported a number of artillery and logistics experts from Austria. But for all the progress that had been made with the officer corps, the rank and file still were of questionable efficiency, so the Emperor refused to unleash his fledgling army piecemeal and prematurely. The strict discipline enforced upon the Imperial army and the draconic measures threatened in case of marauding scared off the worst of the ex-Confederates straight to the conservative rebels, who lacked unified leadership, usually took anyone they could get, and promised rewards they could not deliver. Maximilian’s generals were happy to let them. Miramon and Meija wanted to fight the upcoming civil war with Mexicans; employing a large number of Gringo mercenaries would only undermine the Emperor’s fledgling popularity. While various rebel groups and bands of freelance ex-Confederates ravaged the country, Maximilian concentrated his forces in their strongholds. It seemed the same mistake Santa Ana had made, but Maximilian's forces were of better quality and cohesion, and his generals used the time gained to relentlessly drill them. By early 1868, the Empire struck, prioritizing the more visible conservative and reactionary rebels. They had to fight the leftists and the Imperials at the same time and could be virtually crippled during the spring of 1868. The Imperial victory rendered the leftists stronger as well, to whom the Confederate veterans quickly defected. This perceived position of strength would however be their undoing. Used to traditional warfare between organized armies, the ex-Confederates habitually overreacted to asymmetric threats, and caused more collateral damage and friendly fire casualties than actual harm to the enemy. Their frequently excessive brutality sapped public support from the cause of the rebels. Moreover, the ex-Confederates held the Imperial army in such contempt that they pushed their respective leaderships for a major offensive; surely Maximilian's ill-trained rabble would be a walkover for the men who had marched with General Lee. During the summer of 1868, various leftist groups consolidated their forces and moved to capture several large cities in northern Mexico, clandestinely supplied with weapons from beyond the Rio Grande, courtesy of General Sheridan. Maximilian could hardly believe his luck: The rebels, who would have been unassailable as long as they stayed dispersed, were together and in the open. Although General Miramon had never distinguished himself as much of a tactician before, he decisively defeated the rebels during the fall of 1868, and imperial propaganda was able to play the frequent inability (or unwillingness) of Confederate veterans to discriminate friends from enemies for all it was worth. By late 1868, US weapons supplies to the rebels had been uncovered, and a majority of Mexicans viewed the 1867 rebellion against the Empire as a foreign invasion staged by bloodthirsty, greedy Gringo adventurers. This was the end for the rebellion. Many rebel leaders including Porfirio Diaz were captured and executed in the spring of 1869. Small scale insurgence continued into 1870, but by that time, Emperor Maximilian’s rule was for all practical purposes stabilized and there to stay. In 1871, he gained financial freedom of action by renouncing his debts to France. Napoleon III had made it a personal issue to threaten Maximilian, but with Napoleon deposed and France a republic, Maximilian argued the creditor – the Second French Empire – had vanished in a legal sense, so the deal was off. The French were so busy with the war and the Commune that they hardly noticed; when the Third Republic was consolidated in 1872, there was no way to force the Mexicans to pay up short of war. This however was a no-go, with France’s army crippled and the USA, however they despised the Mexican monarchy, again able and willing to impose the Monroe doctrine to prevent a repetition of France’s 1863 adventure. The matter soured French-Mexican relations for a decade, but Germany and Austria happily stepped in as creditors (the latter for dynastic solidarity, the former to piss off the French), and Mexico’s credit ranking did not suffer. For Maximilian, it was a diplomatic triumph which massively boosted his popularity; there could be no doubt now that he was no one’s puppet. All that was missing to round the picture was a heir, which was no easy undertaking, because Maximilian was widely considered to be impotent due to the effects of veneral disease. When he surprised everyone by declaring the Empress pregnant in 1872, rumors abounded about the child's true fatherhood. These were however short-lived when the imperial pregnancy went awry and the Empress died giving birth to a girl so ugly that any doubts about Maximilian's fatherhood could be discounted. The Infanta received the name Isabel Carlota Sofia Maria Teresa de Habsburgo-Lorena. The Emperor celebrated his grief very publicly, which appealed to the Mexican flair for tragic romance, ironically further enhancing his popularity. Bereft of family (he would never remarry, although continue to have affairs with numerous mistresses), the Emperor decided to distract himself by doing what he had already proven very capable of: He created himself a navy.

5. The Emperor's Admiral

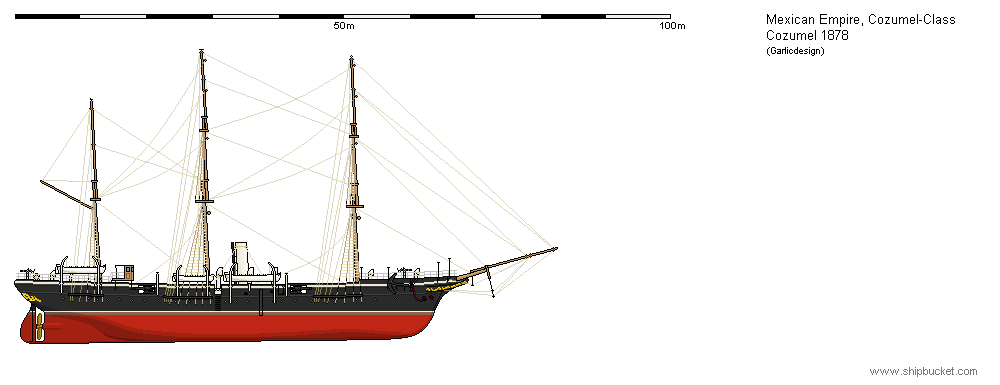

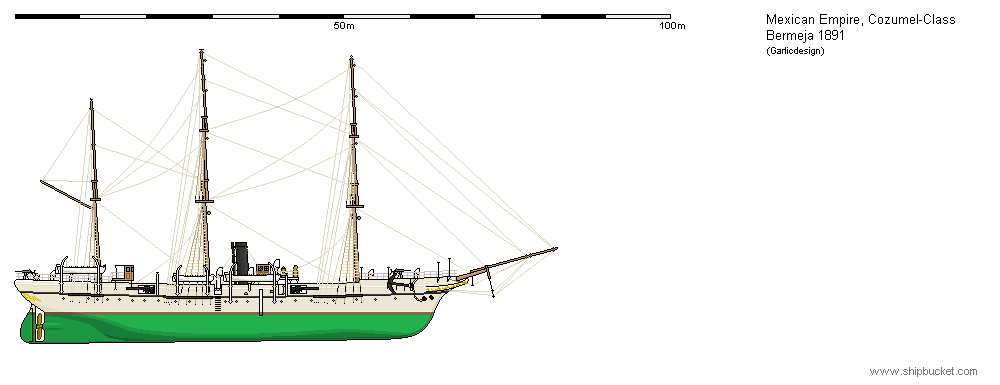

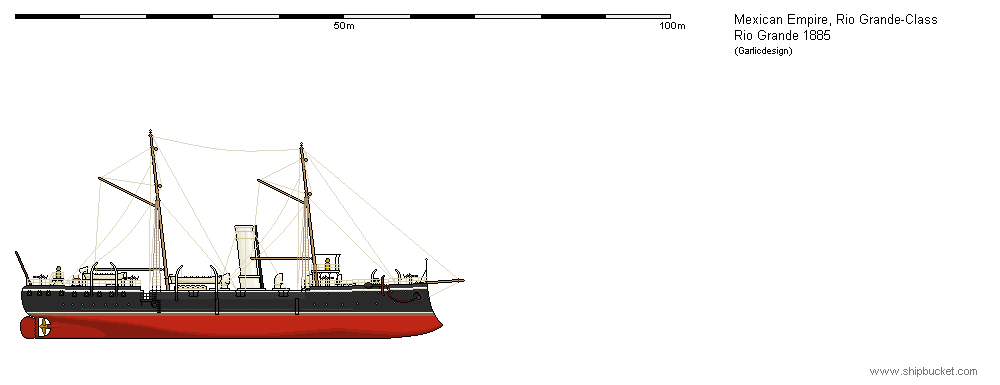

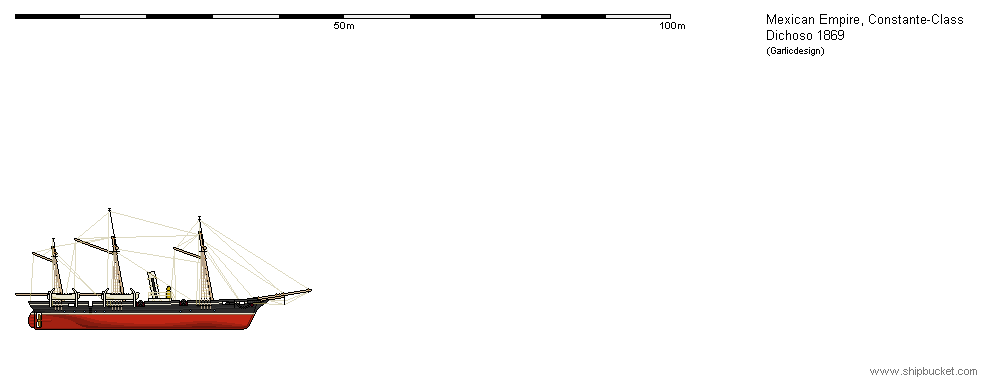

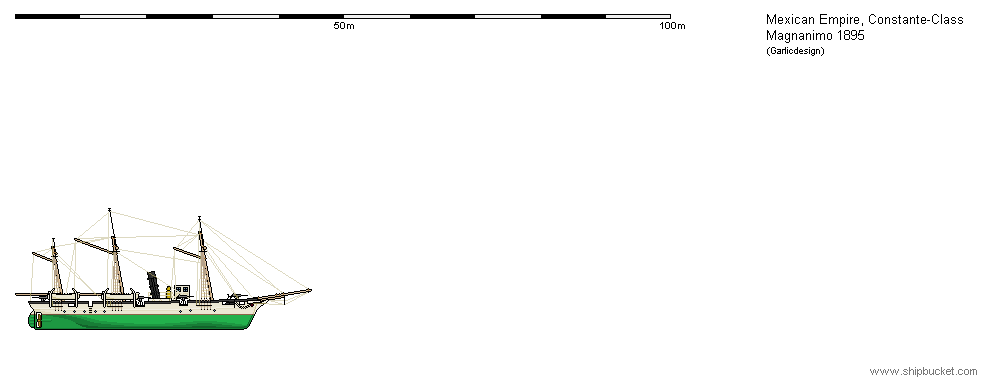

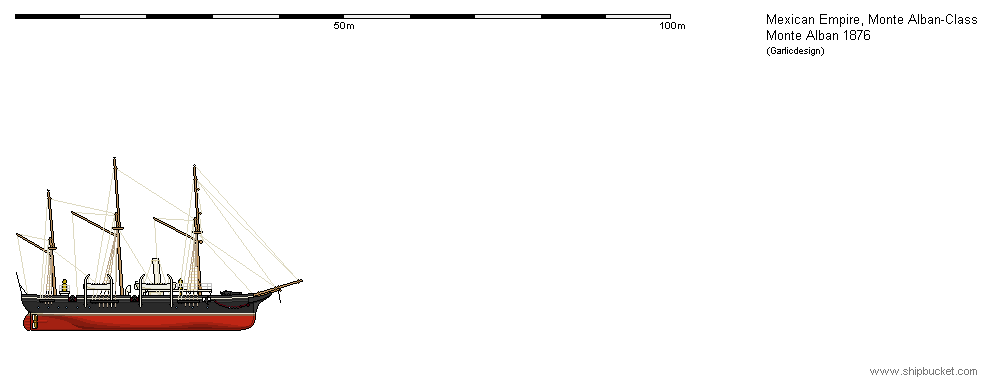

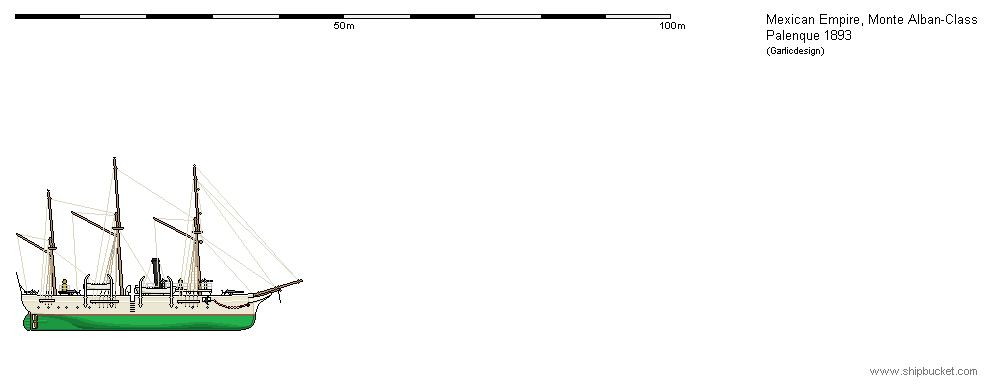

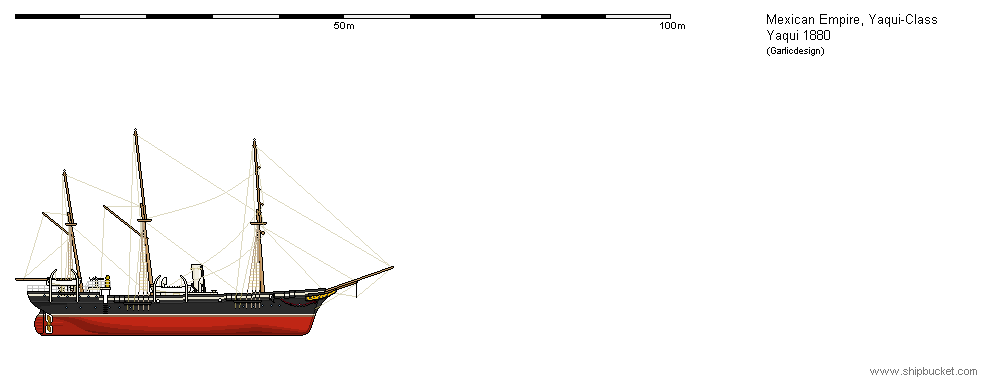

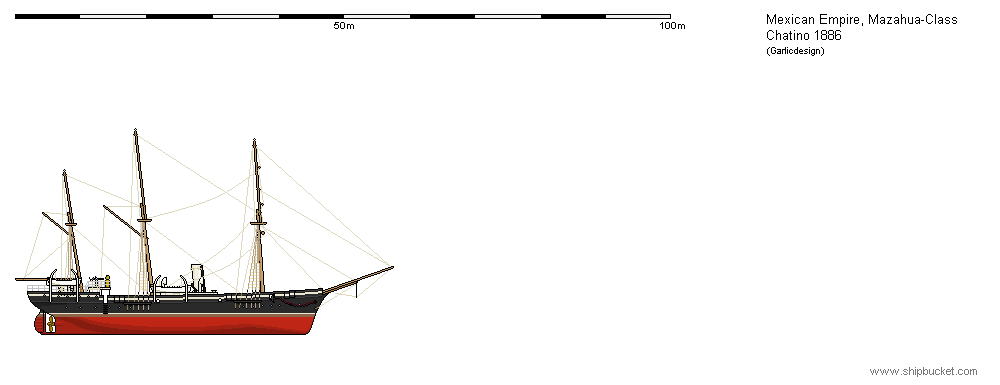

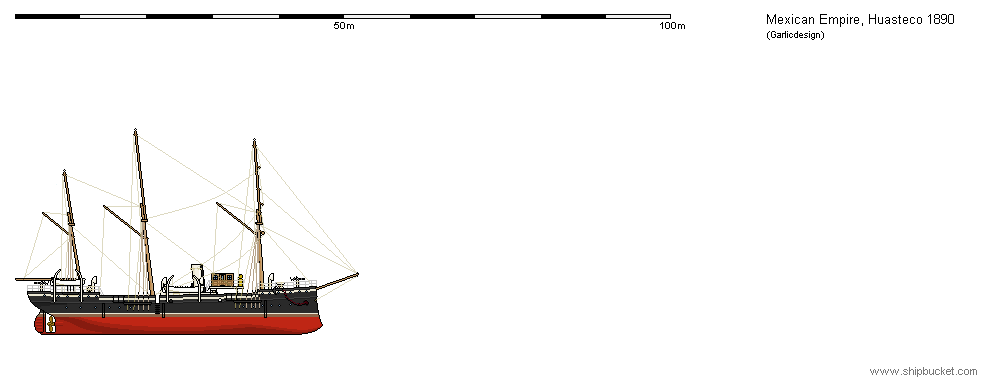

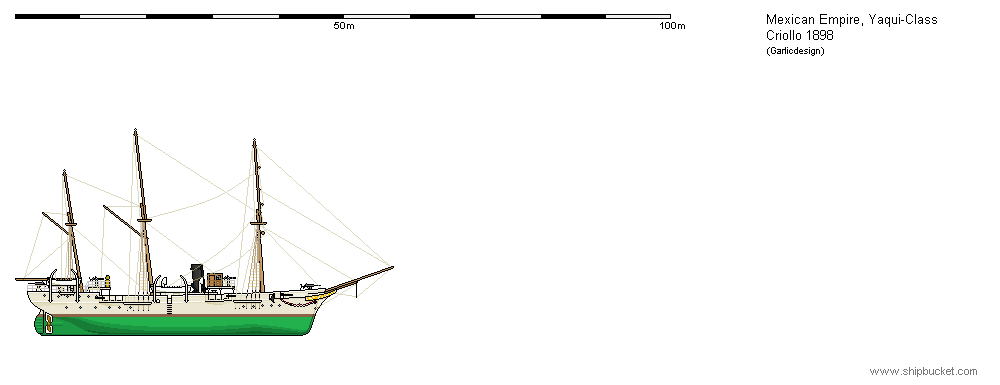

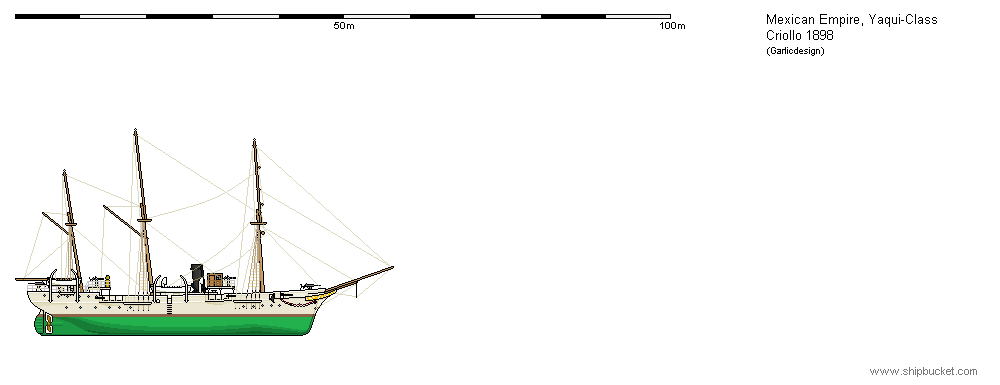

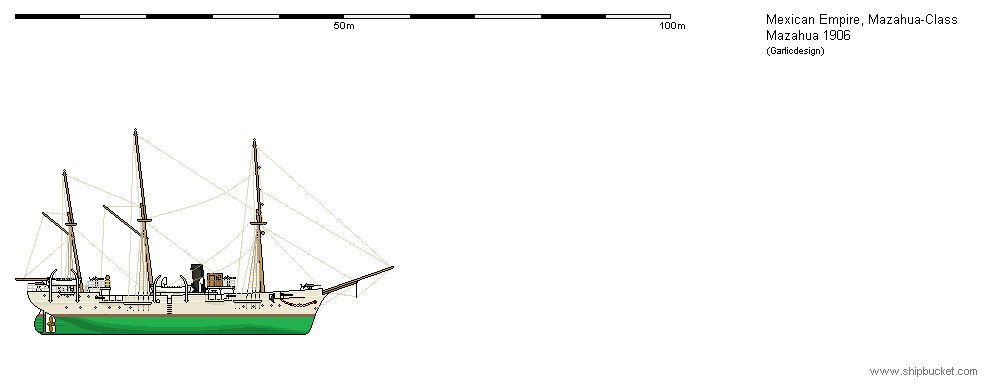

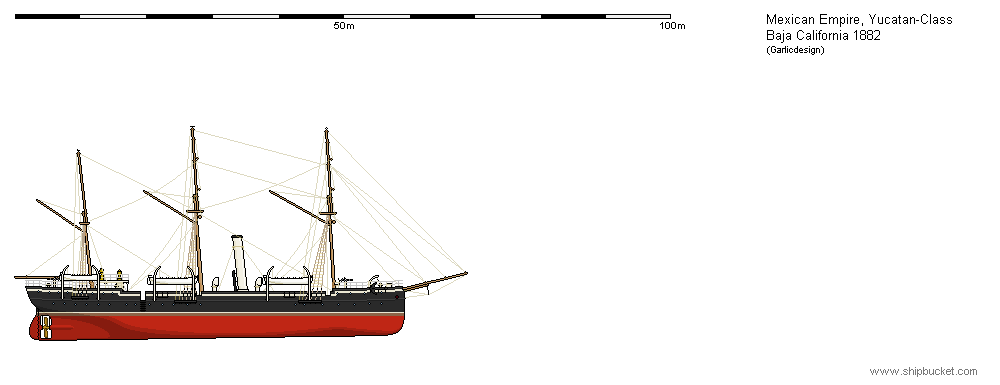

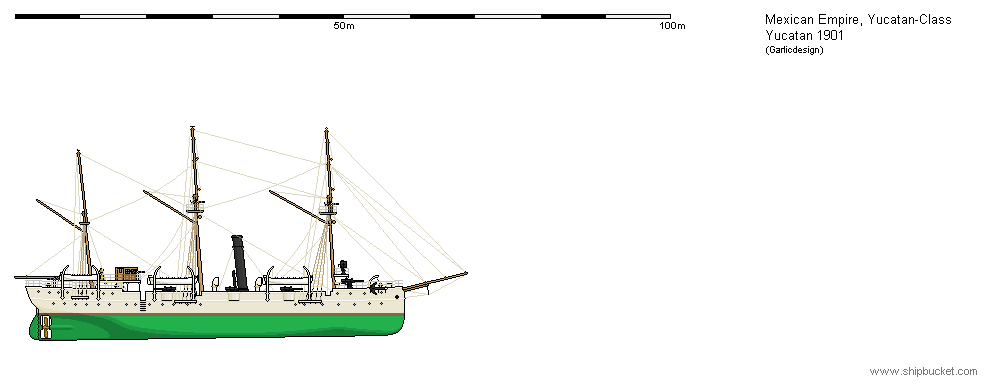

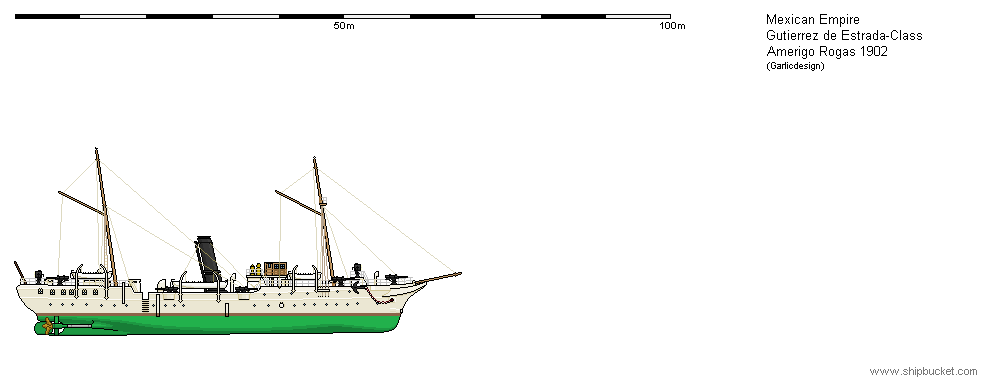

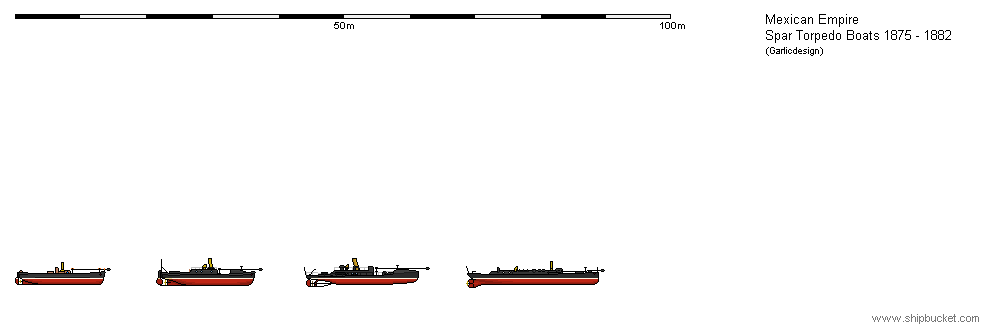

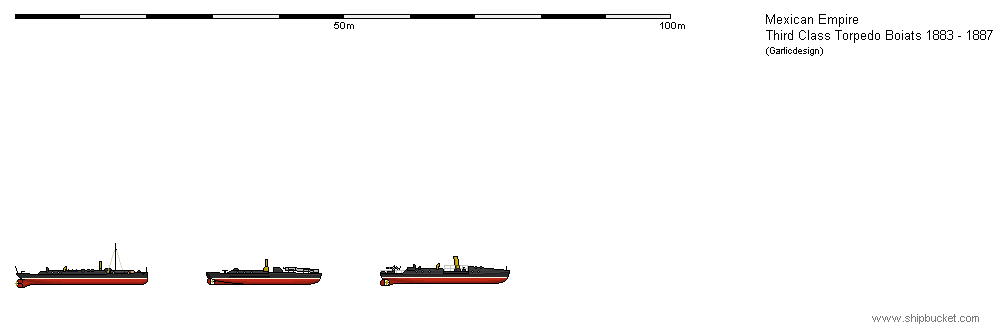

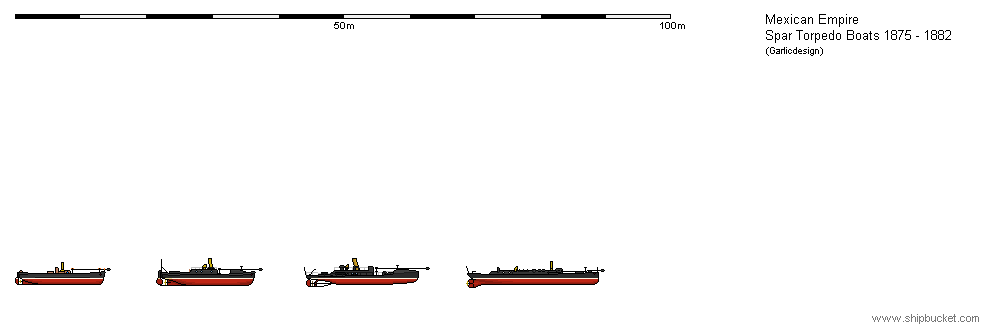

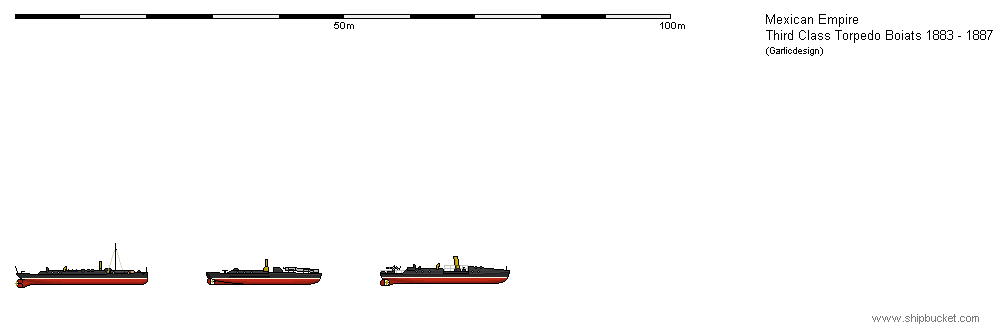

Mexico had possessed no naval forces worth mentioning when Maximilian arrived; whatever steam warships had been available, Santa Ana had sold to the Spanish to finance the 1854 civil war, leaving only a handful of decrepit sailing ships. Maximilian had already purchased four British-built wooden steam schooners in 1866 and an Austrian-built wooden steam sloop in 1868; in 1872, he added a small ironclad and two more steam sloops from Austrian manufacture, and three more British built masted steam gunboats. This was however only the beginning. Maximilian’s ambition was to turn Mexico into a self-sustained naval power with a professional officer corps of the highest quality and the ability to build every kind of warship domestically. To that end, Maximilian managed to secure the assistance of one of the premier mariners of the century. After his victory at Lissa, Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff never had it easy with the Austrian bureaucracy. He had almost resigned in that year after the imperial administration had accused him of fraud because of the size of his victory dinner (little wonder there; his victory had not prevented the Austrians from losing the war). His resignation was refused, but the KuK administration's ongoing effort to undermine his work - he was viewed as the proverbial crab trying to climb out of the bucket which needed to be drawn down to the general level of complacency, inefficiency and corruption - strained his health and his nerves. Fortunately for him, the latter gave way before the former, and he resigned his position for a second time in September 1870 after a row with the government over its decision to limit the battlefleet to eight ironclads, while Tegetthoff wanted twenty. As he was in poor health at that time, one might fear that any continuation of the stress he was suffering might have killed him sooner rather than later. Tegetthoff decided to accept a long-standing invitation of his former C-in-C, Maximilian of Mexico, who had recognized Tegetthoff's talents very early during his tenure as head of the Austrian navy and rapidly promoted him. The admiral traveled to Mexico, where he arrived in December 1870 to a lavish welcome. During the following year, he recovered his health, mostly living on an imperial resort in the warm and dry climate of Baja California; in fall, he traveled the country, whose economy was beginning to flourish again, with the civil war for all practical purposes over. Tegetthoff, who already was fluent in Italian, easily picked up Spanish, and with his spirits and energy restored, he did not think twice when Maximilian offered him a job. On April 1st, 1872, Wilhelm von Tegetthoff was appointed Mexico's first-ever Minister of the Navy, receiving a promotion to full admiral (the next ranking Mexican naval officer at that time was a Captain) at age 45. The first thing Tegetthoff did was upgrading the extant bases at Veracruz and Acapulco, adding three more at Tampico in 1873, at Topolobampo in 1878 and at Chetumal in 1882. He founded a Naval Academy at Veracruz in 1873 and Naval Yards at Tampico in 1875 and at Veracruz in 1880. The yards were initially for maintenance only, but soon became more proficient and capable of turning out warships. Additionally, the Emperor applied various measures to attract foreign investment to initiate domestic iron ore mining and establish a Mexican steel industry; the latter venture never really took off, though. Foreign instructors – initially Austrian, later British and German - were employed to turn Mexico's fledgling officer and deck officer corps into a professional fighting force. This sort of groundwork had priority over the acquisition of new ships in the first years; between 1872 and 1878, only a handful of spar torpedo boats were purchased. That year however, Tegetthoff considered all foundations laid for a contemporary fleet, and started to buy. Gunboats were built in Mexico from the start; only a few prototypes were imported. Large or high-performance ships still needed to be built abroad, but there always was a focus on acquiring their plans and developing the capability to build domestic copies. In 1879, no less than four ironclads were purchased. One was newly built at Trieste to requirements formulated by Tegetthoff himself, the other three were bought from the British government which had acquired three former Turkish and Brazilian ships during the Russian War Scare of 1878, only to realize they had no real requirement for them. In the following decade, additional cruisers and torpedo gunboats were added to the fleet, and in 1885, the first Mexican-designed cruiser (at the same time the last iron warship built for the Imperial Navy) was laid down at Tampico. During this buildup, the performance of Mexican crews improved from farcial to adequate, and the first generation of home-grown professional officers was steadily improving their proficiency. This development was not without foreign political repercussions. The Americans had ignored Tegetthoff’s work for a long time; a 12-year period of neglect during the Grant and Hayes administrations reduced the Old Navy to near uselessness. The USA was busy with internal issues during that time, and it took them till 1885 to realize they had been outpaced by their despised southern neighbors. The USN still outnumbered the Mexican fleet, but virtually all American ships were obsolete, and the extant ironclads were all of the coastal or riverine type. In contrast, the Mexican ironclads Mexico and Imperatriz Carlota were the most powerful oceangoing warships in the Americas, with no equivalent in the USN; only the big Thiarian central citadel ironclads Conlan and Caithreim were remotely their equal. This realization was the alarm signal that prompted the Arthur administration to fundamentally renew the USN.

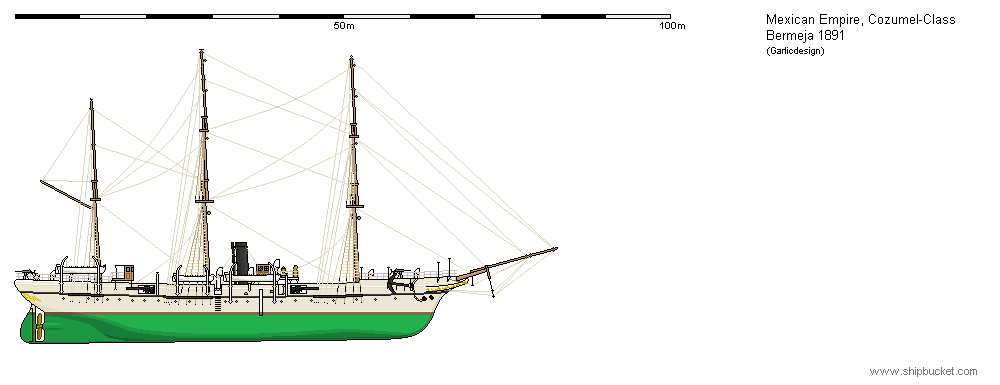

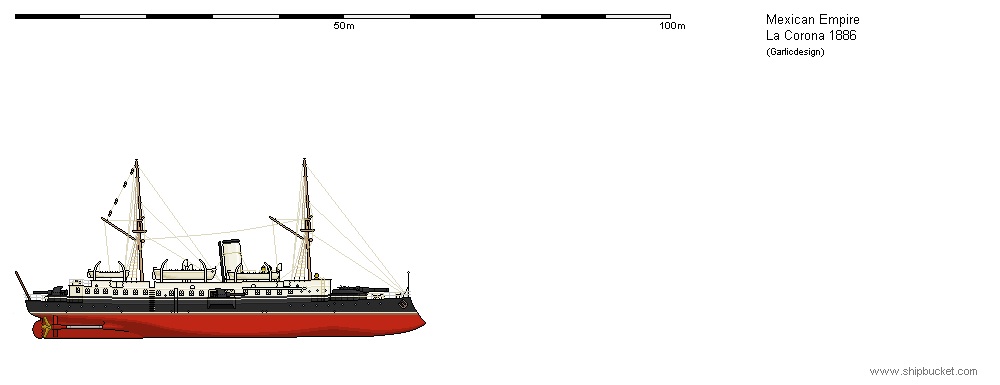

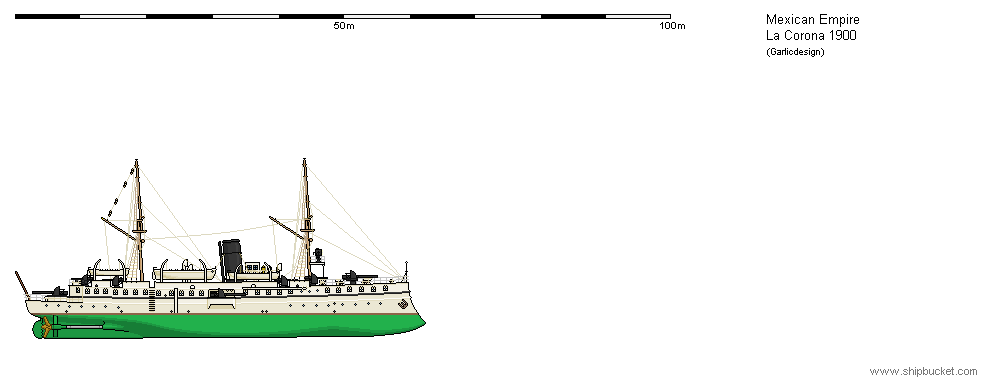

6. Spanish troubles

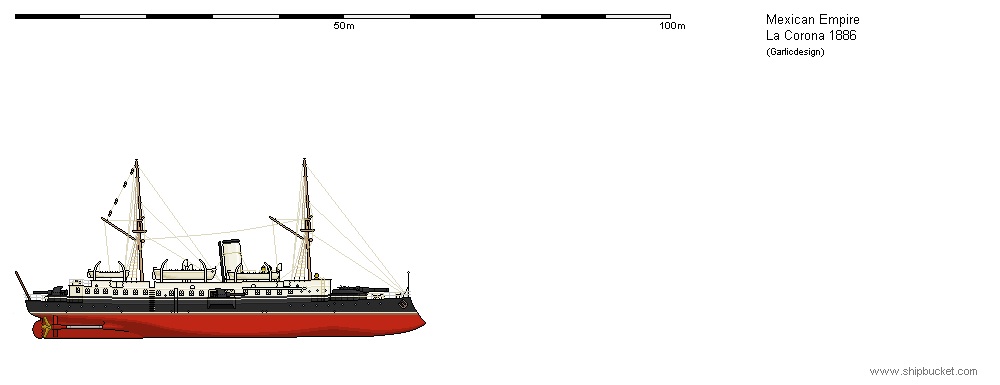

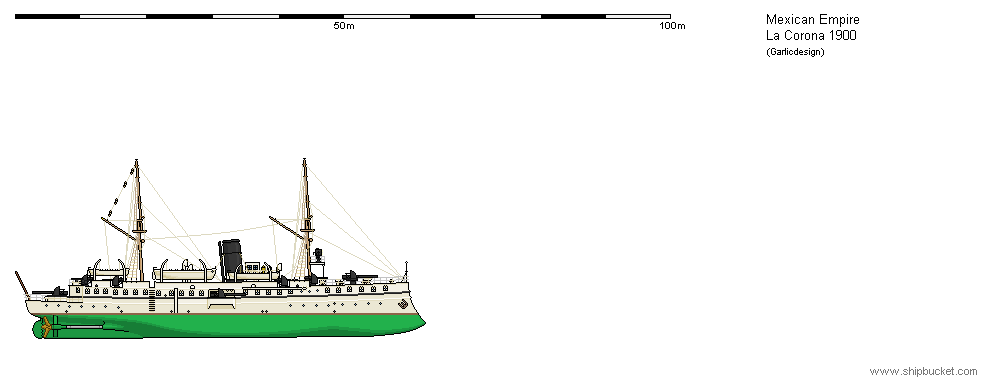

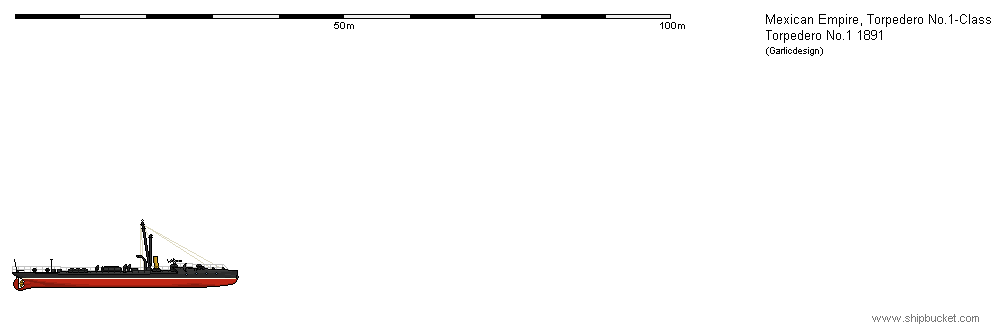

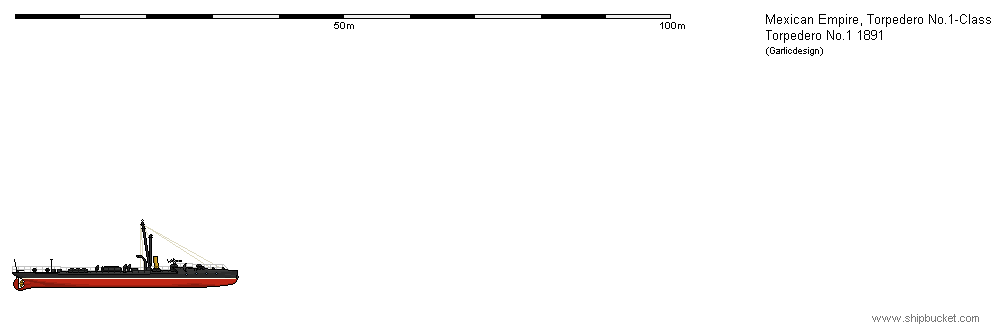

The year 1885 saw the first test for the fledgling Mexican fleet. When the Spanish king Alfonso XII suddenly died that year, progressive elements launched a poorly planned and ultimately botched coup d'etat against the regency of his widow Queen Maria Christina, who had yet to give birth to Alfonso's son, the future Alfonso XIII. Given her advanced state of pregnancy, the Queen - daughter of Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria and thus a cousin of Maximilian's - preferred to leave the country till things were sorted out, and boarded a ship for a spontaneous visit to her relative in Mexico. She made the mistake of using a Spanish-flagged ship, which was captured by rebel forces within sight of the Mexican base on Bermeja Island, and brought to Cuba. When Maximilian got wind of this outrage, he demanded his cousin’s release, and when the rebels did not react, he sent his fleet under Tegetthoff's personal command to Cuba. Tegetthoff, flying his flag on the Imperatriz Carlota (he got seasick on the more powerful, but rather too lively Mexico), engaged an inferior Spanish force consisting of a broadside ironclad, a floating battery and some gunboats in battle of Casimba. During this one-sided affair, the Mexican ironclad Aguila (Capt. Perez Valence) sank the Spanish ironclad Mendez Nunez, which became the last ever capital ship to be sunk on purpose by ramming. The small floating battery Duque de Tetuan was shot up and sunk by the Mexican flagship, and the Spanish gunboats fled as fast as they could steam. Tegetthoff then proceeded to blockade Santiago de Cuba, but soon after the battle of Casimba, the coup in Spain collapsed and the Queen Regent was released to return to Spain in triumph. This humiliation at the hands of a third-rate naval power - and a former colony to boot - triggered a vigorous Spanish reaction; a far-reaching programme to rebuild the run-down Spanish fleet was launched the year after, which resulted in the acquisition of six battleships and eight large cruisers, plus substantial light forces, over the next ten years. The Spaniards also began to fortify Guantanmo Bay for use as a naval base in a future conflict. Tegetthoff was styled Duque de Tampico upon his return; when he asked for a - by the standards of the time - outrageous sum of money for another large fleet building programme, it was granted without a second thought. Under the 1886 programme, Mexico’s first steel ironclad and two large protected cruisers were ordered in Austria, and three small cruisers from domestic yards; one of them was the first large warship built at the second naval yard at Tampico in 1890. The first four Austrian-built seagoing torpedo boats were acquired in 1888, and a big battleship – at 10.000 tons the largest in the Americas – was laid down at Trieste that same year. By that time, Tegetthoff, as much the creator of Mexico’s Navy as the Emperor himself, had already retired, aged 60; events however would force him to return two years later.

7. Clash with the Titan

The French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had overseen construction of the Suez channel in the 1870s, had to witness it fall into the hands of Great Britain, the old enemy of his native France, practically immediately upon completion. Undeterred, he proceeded to head an even more ambitious project in 1881 and started construction of a channel through the Isthmus of Panama. Technical difficulties and cost overruns resulted in the bankruptcy of his company in mid-1889, and he asked the French government to step in. When the Harrison administration in Washington got wind, they cited a violation of the Monroe doctrine and threatened with war if the French acquired such a crucial strategic position in Central America. Although the French navy at that time had 25 ironclads in commission and could have walked straight through the USN at half-power, France’s government, still careful after its defeat against Prussia in 1871, backed off. Emperor Maximilian figured the Monroe doctrine did not to apply to Mexico, being an American country after all, and in 1890 proposed to Lesseps and the Colombian government to step in, in exchange for control rights over the completed channel. President Harrison was outraged by this impertinence of some inbred Balkan Autocrat (original tone) and threatened Maximilian with the direst consequences if he proceeded on his course; Monroe doctrine or not, the USA would not tolerate anybody except themselves to acquire a channel across the Isthmus. In response to Harrison's intentionally insulting statement, Maximilian asked Tegetthoff to come out of retirement and lead his fleet on a foray across the Caribbean towards Key West to show his resolve and determination. President Harrison - warned in vain by his advisors that the USN's inventory was outdated and still had no oceangoing battleships at all – ordered his fleet, consisting of little more than four protected cruisers, an unprotected cruiser and three gunboats – to sea from Key West to face off the Mexicans. Simultaneously, he issued a part mobilization of the US Army and moved several crack units to Texas. Maximilian's military advisors now developed cold feet. Although the USA at that time was at the historical nadir of its military power, its sheer size – the USA had five times the population and ten times the economy of Mexico – justly convinced them that they could not win a full-scale war. Better to show force than to use it, Maximilian's advisors argued, and some solution favorable to Mexico might be obtained at the negotiating table. At that stage of deliberations, both fleets met about 50 miles southwest of Key West (Cayo Hueso) in the early morning of May 29th, 1890, in what was to become the eponymous battle. Tegetthoff, completely outnumbering the Americans with a fleet of four ironclads, two protected and two unprotected cruisers, plus four gunboats, decided that refusing to salute the US flag would be a fine way to show resolve and determination. This calculated insolence provoked a warning shot by USS Charleston, which quickly developed into a shootout, leaving three US protected cruisers damaged, the brand new USS Charleston quite severely, and the old USS Trenton afire and in a sinking condition, against minimal damage to the Mexican ships. The Americans then retreated to their base, leaving the Mexican fleet in control of the sea. When the news broke, the American public was flabberghasted and, after the initial shock had worn off, roared for revenge for what the press called an act of piracy on Tegetthoff's part. International voices were more benign; even the British, who had no sympathies for the Habsburg Empire and its Mexican seedling, were of the opinion that the US commander, Admiral Gherardi, who died of his wounds soon after return, had handled the incident poorly by not waiting for the US main force of four large monitors available at Key West. Although President Harrison knew that an US invasion in Mexico would cause more trouble than it was worth, he played his cards well and - by pretending he could not resist the internal pressure of the war party - scared the Mexicans into a negotiated settlement that gave the US everything they wanted. In the treaty of Tijuana, Maximilian had to forsake all ambitions in Panama, sack Tegetthoff and pay reparations for US losses in the ‘Battle’ of Cayo Hueso; despite such expense, the Mexicans could afford to order further modern warships under the 1890 emergency program. Tegetthoff and his second-in-command Rear Admiral Cordona were celebrated in Mexico City. After all, the first shot had been fired by the Americans, and they were considered the defenders of Mexico's honor. Cordona was made Minister of the Navy, and Tegetthoff, as a reactivated pensioner, could afford to graciously retire from his post, robbing the Americans of the satisfaction of having forced Maximilian to get rid of him. After the wave of hero worship, which he thoroughly enjoyed, had ebbed down, Tegetthoff embarked upon a journey to Austria in October 1890, where he got another round of it. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany dropped everything to meet him and is reported to have embarrassed himself by acting like a teenager in the presence of a pop star. But the most famous Admiral of the 19th century outside Great Britain would not get the time to enjoy his retirement. Acclimatized to Mexican weather, he promptly caught pneumonia in the following central European winter and died in April 1891, aged 64.

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

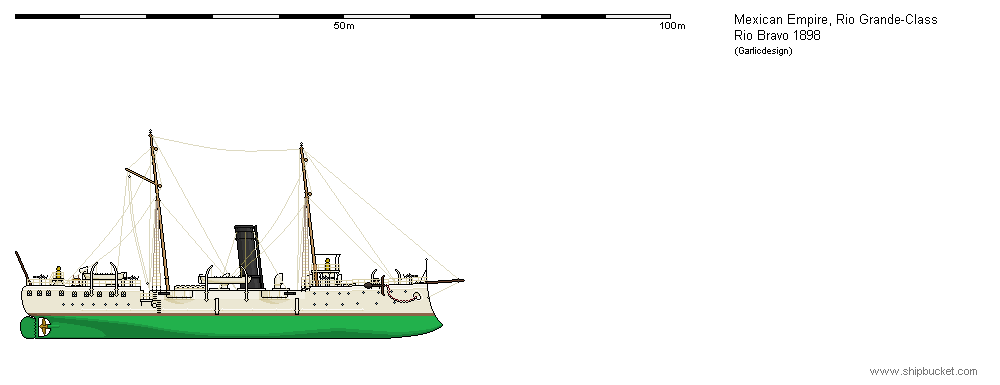

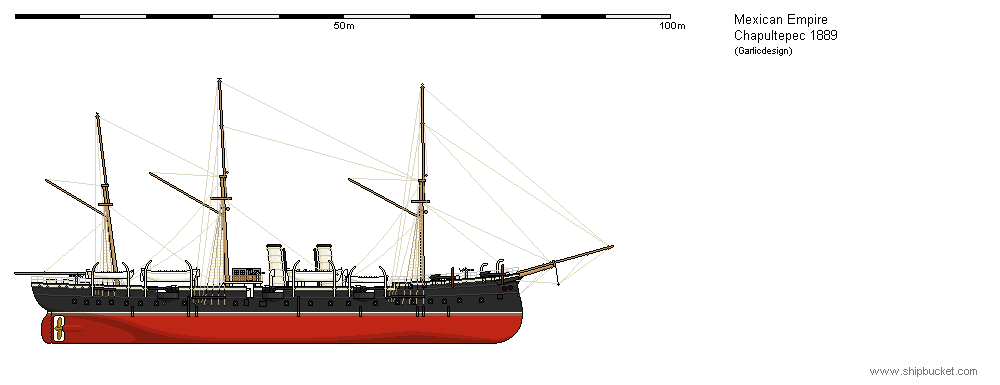

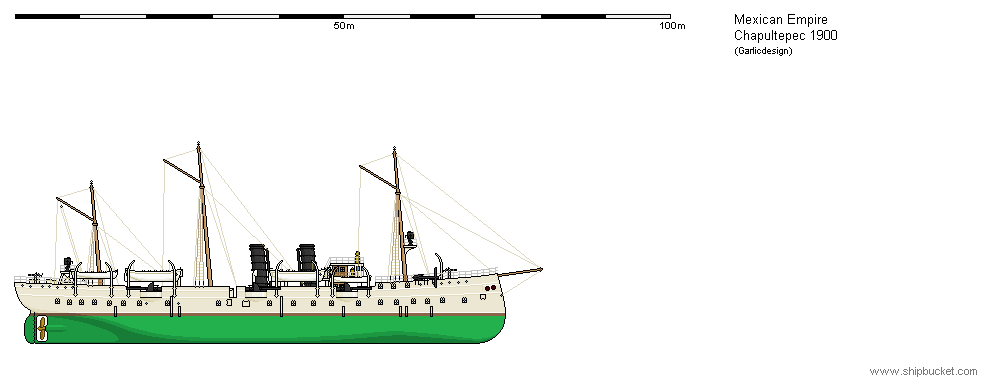

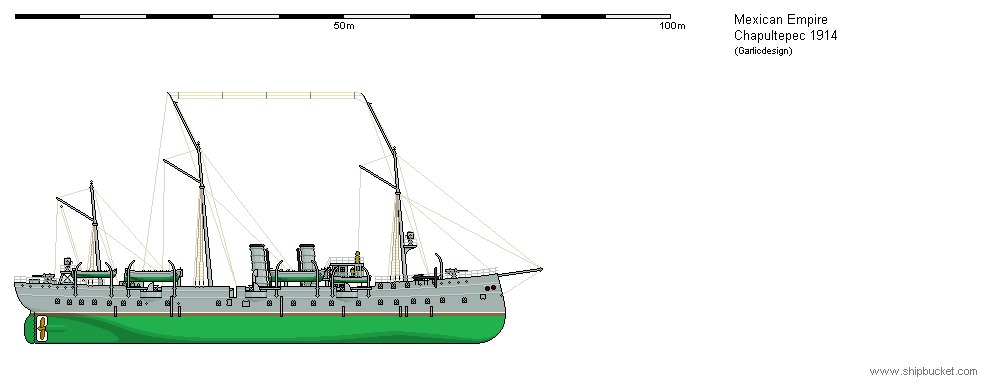

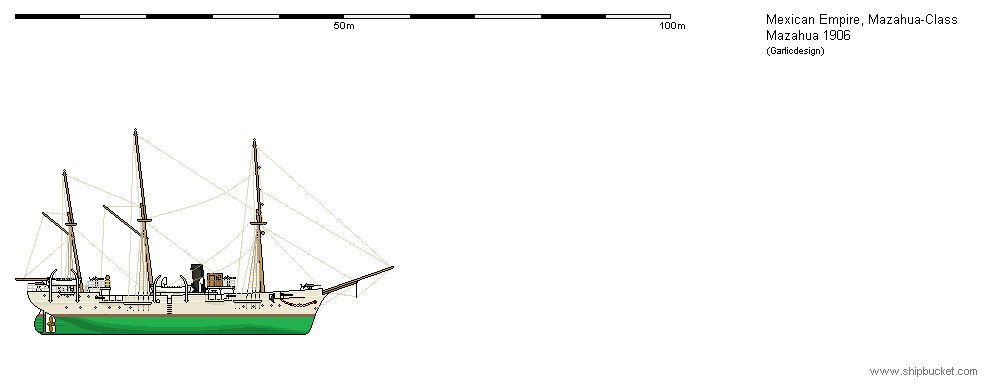

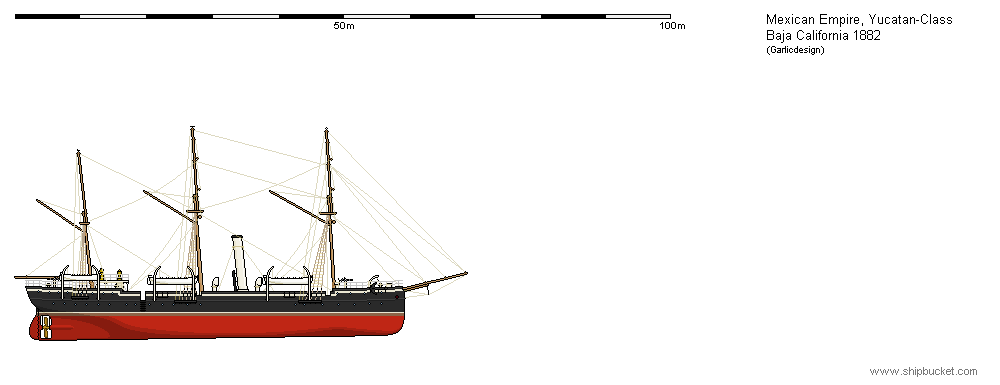

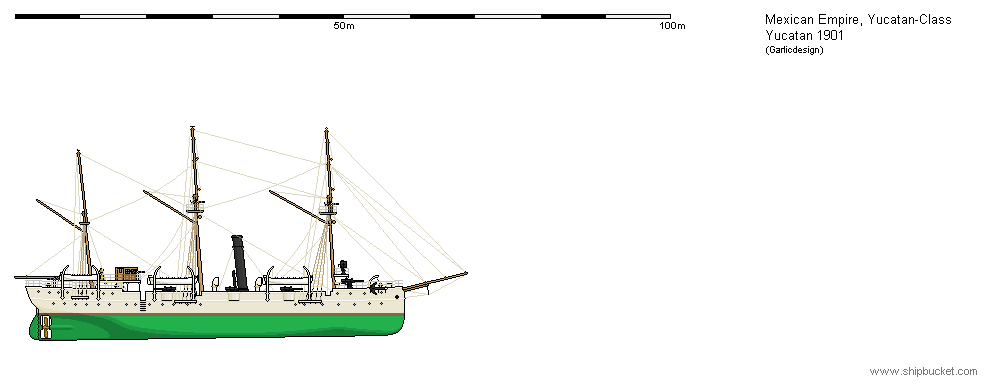

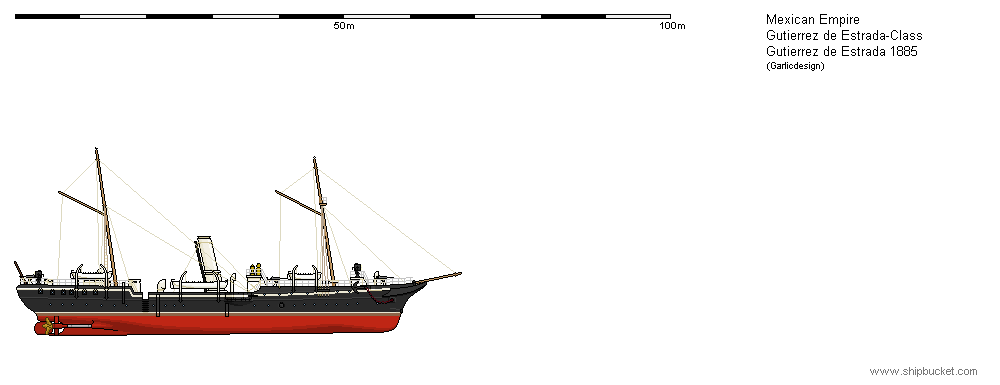

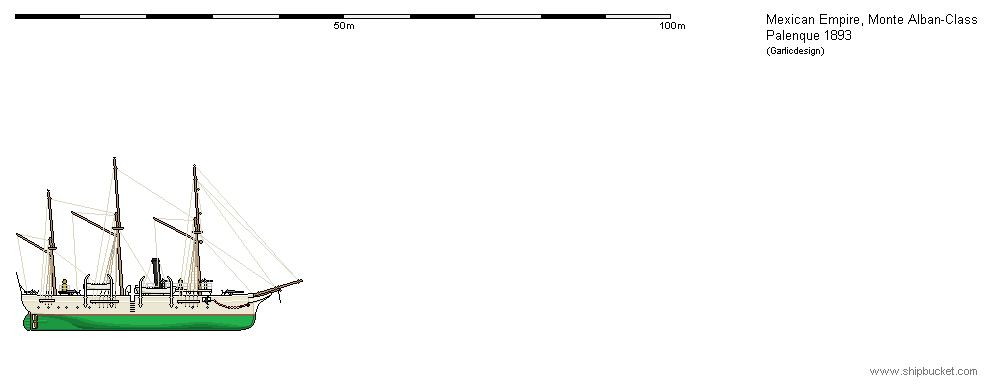

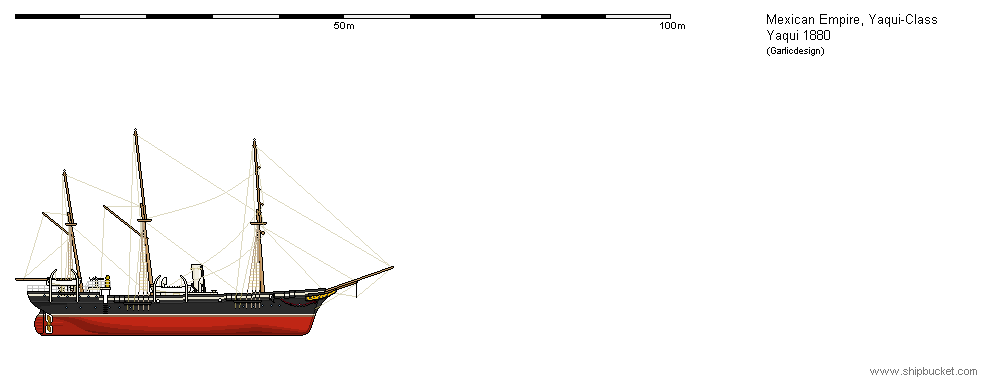

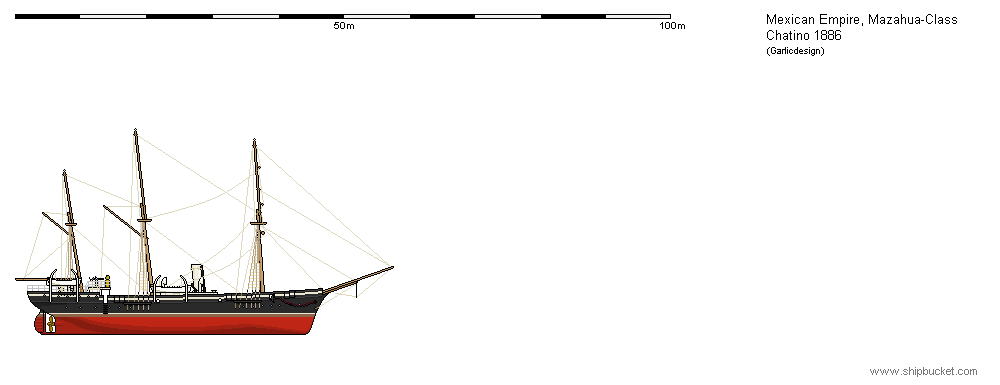

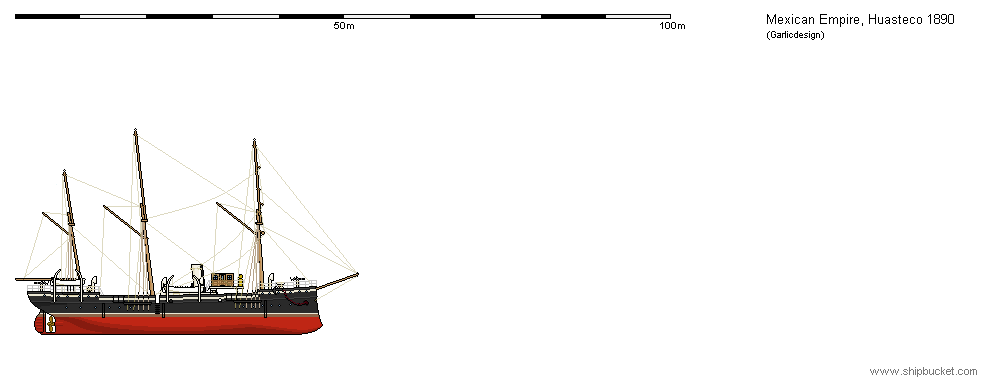

Mexican Warships 1861 – 1891

A. Battleships

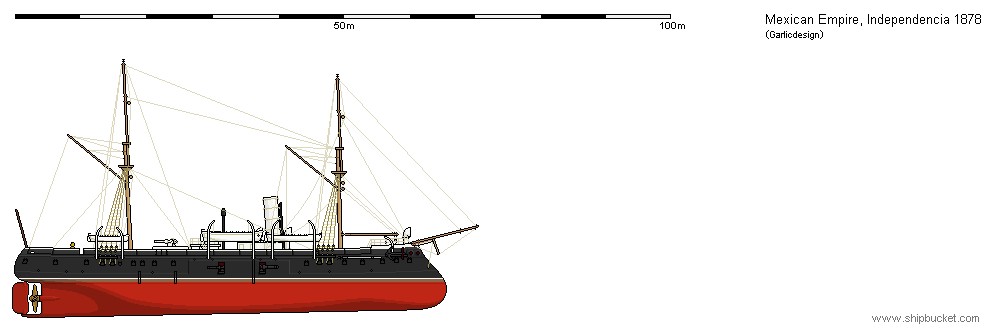

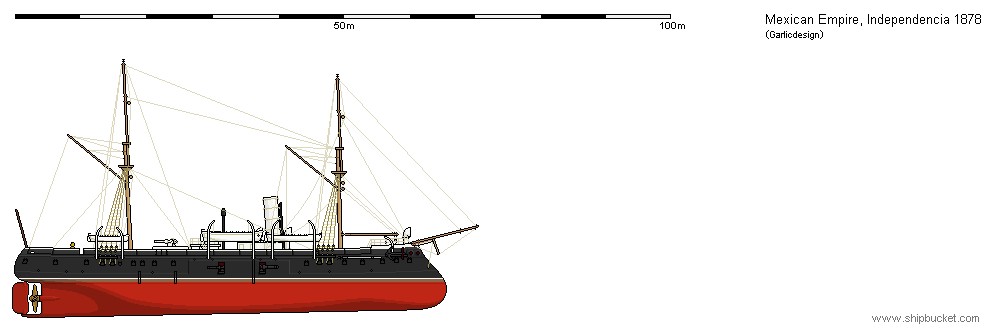

1. Independencia

Half-sister to the Ottoman Icaliye, this small, corvette-sized ironclad was under construction at STT for the Persian Empire, to act as that nation’s flagship under the name Artemiz, named for a female naval commander serving high King Xerxes in the Persian wars (yes, the antagonist in 300 – Part 2 was based upon a real person). Predictably, financing went awry, and early in 1871, the incomplete hull was offered to the highest bidder, initially with little success. Late in 1872 – completion had been suspended pending purchase – Emperor Maximilian personally signed a contract of purchase for what would become the first flagship of the Imperial Mexican navy. She arrived in Mexico in May 1873 after using her schooner rig to cross the Atlantic without employing her machinery.

Displacement:

2.230 ts mean, 2.650 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 66,00m, Beam 13,0m, Draught 5,05m mean, 5,50m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Horizontal Compound, 2 rectangular boilers, 4.050 ihp

Performance:

Speed 12 kts maximum, range 1.500 nm at 8 knots

Armour:

All wrought iron. Belt 152mm on 178mm wood over complete length, battery 114mm; barbette 127mm

Armament:

2x1 229mm/14 Armstrong RML, 3x1 178mm/16 Armstrong RML

Crew

150

Independencia was mostly used for training throughout her career. She was relieved as fleet flagship in 1879 by the big turret ship Mexico, but was present during the battle of Casimba during the First Spanish war in 1885; she engaged a Spanish gunboat and damaged it, forcing it to retreat.

After the battle, Independencia was modernized. She shed her sailing rig, received searchlights and new guns: all her muzzle loaders were replaced by modern 150/35 Krupp BL pieces. She also received two 87/22 Skoda BL from storage, two 47/44 Skoda QF and two 47/33 Hotchkiss revolvers, the latter mounted in her fighting tops.

When she re-entered service in 1888, she was re-classified from armored corvette to armored gunboat and stationed at Tolopobampo in the pacific. She returned to the Caribbean in 1893 to serve as a training vessel. In 1897, she was hulked, and in 1910, the hulk was broken up.

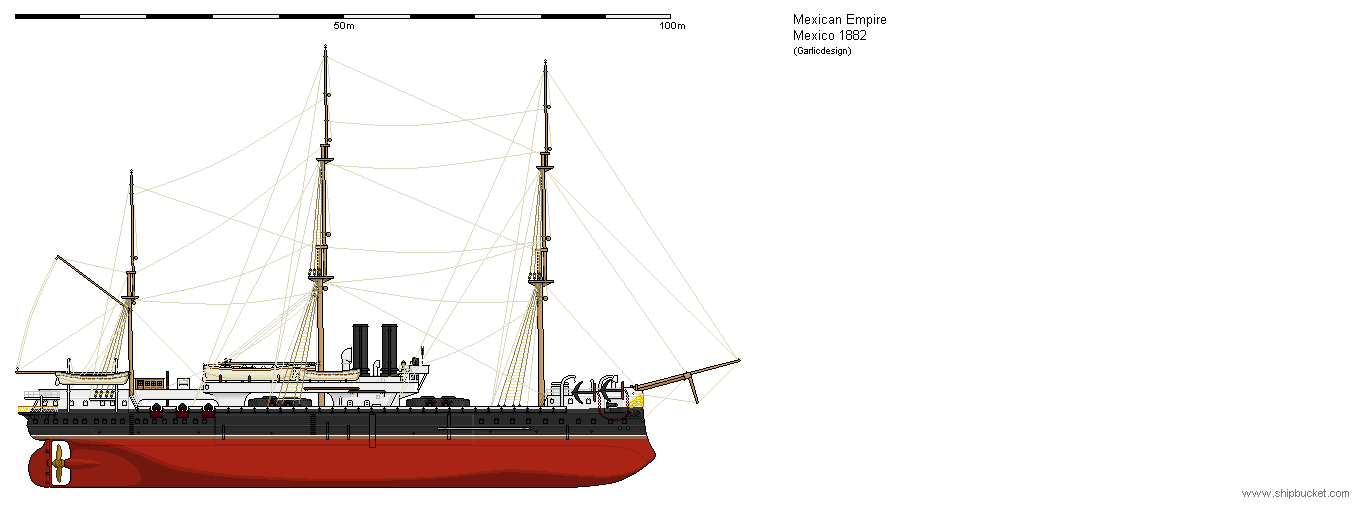

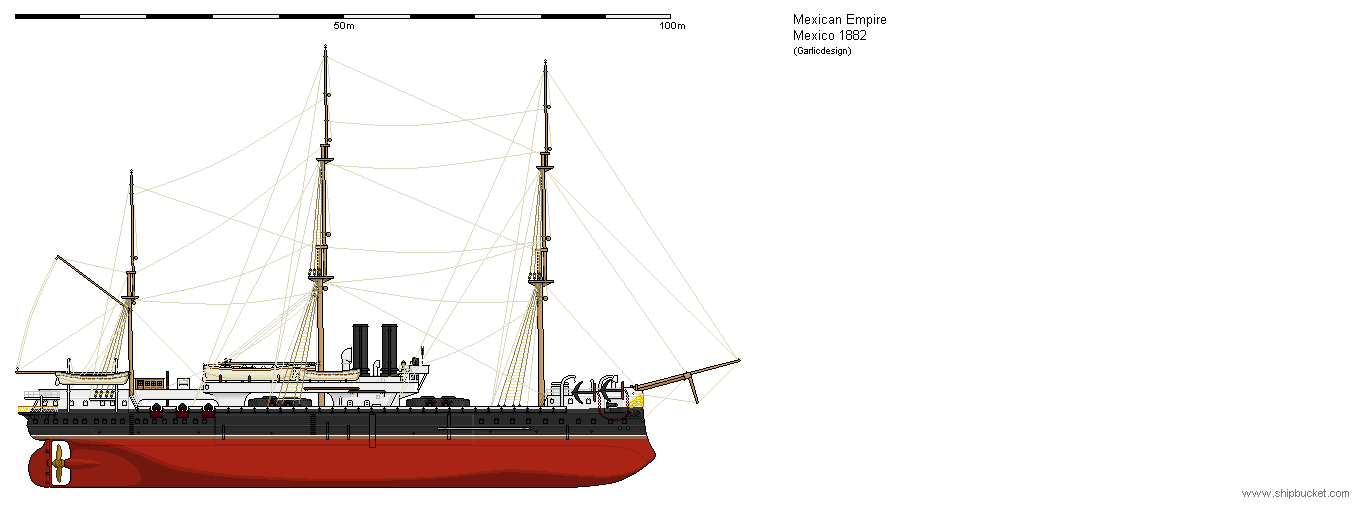

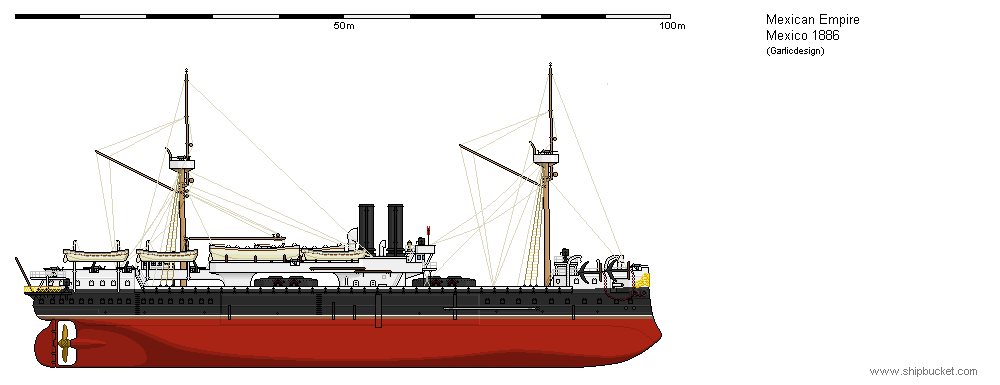

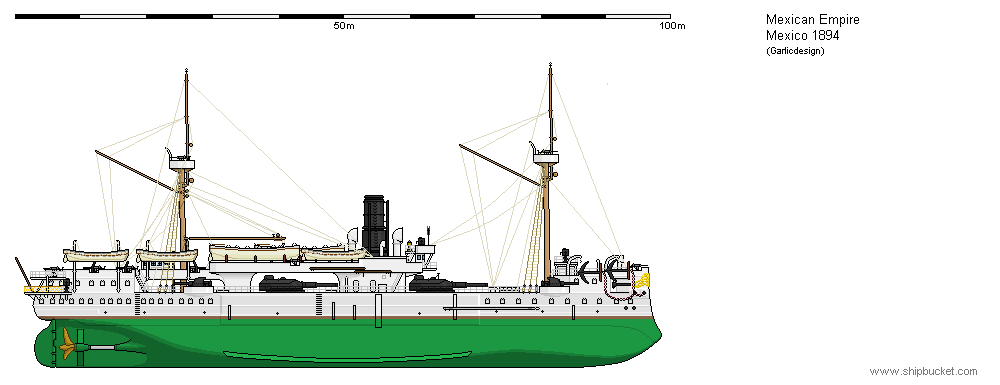

2. Mexico

Originally ordered by Brazil under the name Independencia in 1872, this ship was one of four hulls purchased by the British government in 1878 while still under construction when war with Russia was urgently expected. Construction had been suspended for some time because the Brazilians lagged in payments, and completion took till 1881. Upon purchase, she was renamed Neptune for RN service, but the Admiralty was not happy with her. Despite her ponderous size, Neptune was overweight and barely stable, and she was hardly maneuverable under sail. When the Mexican government expressed interest in buying her in 1880 (she was running machinery trials by then), the British were glad to be rid of her. By far the largest vessel ever acquired by Mexico, she was named for the country and destined to serve as the Imperial flagship. She roused quite an uproar when she arrived in 1881, being the largest and most powerful warship in all the Americas, eclipsing the Thiarian Conlan and Caithreim and outclassing anything in the USN’s inventory.

Displacement:

9.130 ts mean, 9.960 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 97,40m (110,30m with bowsprit), Beam 19,20m, Draught 7,45m mean, 8,10m full load

Machinery:

1-shaft Horizontal Single Expansion, 4 rectangular boilers, 8.000 ihp

Performance:

Speed 14 kts maximum, range 1.500 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

All wrought iron. Belt 305mm on 457mm wood; Ship ends 229mm on 317mm wood, citadel 254mm; turrets 330mm maximum; deck 76mm maximum, CT 203mm

Armament:

2x2 305mm/12 Whitworth RML, 2x1 229mm/14 Whitworth RML, 6x1 100mm/21 Whitworth BL, 2x1 350mm torpedo launchers (forward, above water)

Crew

540

Despite her doubtless strengths – her armament was state of the art, and her armor protection was excellent – her poor level of stability made her virtually useless for day-to-day service. Whenever she was underway, she would roll so badly that everyone expected her to capsize anytime soon; even seasoned sailors serving on her were incapacitated en masse by sea sickness. Although initially feared, she soon became a laughing stock, especially for the US press, to whom she exemplified the farcial state of the Imperial Mexican navy.

After less than three years of service, she was taken in hand in an attempt to cut top weight, She lost one of her masts and the whole sailing rig. Her obsolete 100mm guns were replaced with six 57mm and eight 47mm QF guns. A slight improvement was achieved; the level of stability now was only annoying rather than positively dangerous. She missed the First Spanish war due to the refit.

Mexico belonged to the fleet engaging the USN in the Key-West-incident, but nearly sank in a subsequent storm. She was decommissioned upon return and again thoroughly rebuilt. She was entirely gutted, losing her whole machinery and both 305mm turrets. New twin-shaft VTE-machinery with cylindrical boilers generating 9.600 ihp for 15 knots were installed, and a completely new main armament of four 240/40 Krupp BL guns in thinly armored gun houses was fitted. The iron citadel armor was replaced by 150mm nickel steel, and the 229mm bow chasers were landed. Six 150/35 Krupp BL guns were mounted as new secondary armament; the tertiary battery was retained. When she re-emerged in 1894, she was little changed externally, but her stability deficit had really been tackled, and she was rated a much more satisfactory sea boat than ever before.

Mexico again joined the active fleet and formed the second division, together with Rio Brazos. She was present at the battles of Mayaguana and Santiago in the Second Spanish war and engaged the Spanish line of battle; her gunnery proved effective, and she was credited with sinking the Spanish coast defense ironclad Guipuzcoa during the battle of Santiago. But the 61 broadsides fired during both engagements overstrained her old hull, which was not designed to withstand the recoil forces of modern long-barreled guns. Upon inspection immediately after the war, she was ruled structurally deficient and subsequently hulked. She remained available as an accommodation hulk and stationary guard ship at Veracruz. By 1912 she had become so leaky she sank at her moorings. She was salvaged and broken up in 1913 through 1915.

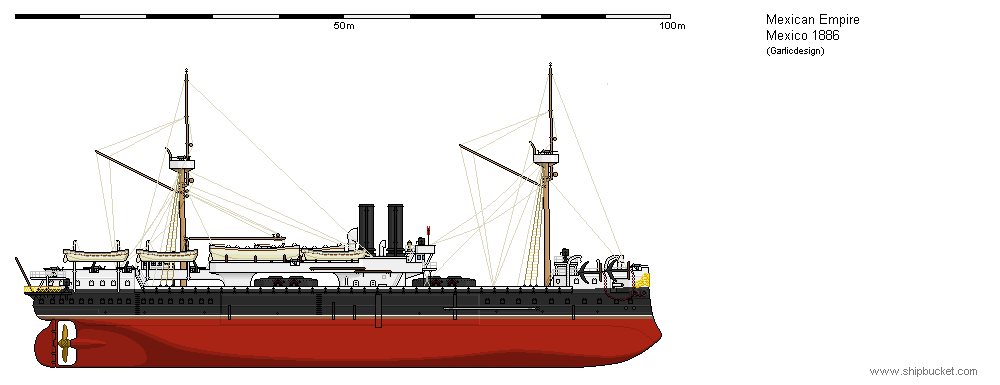

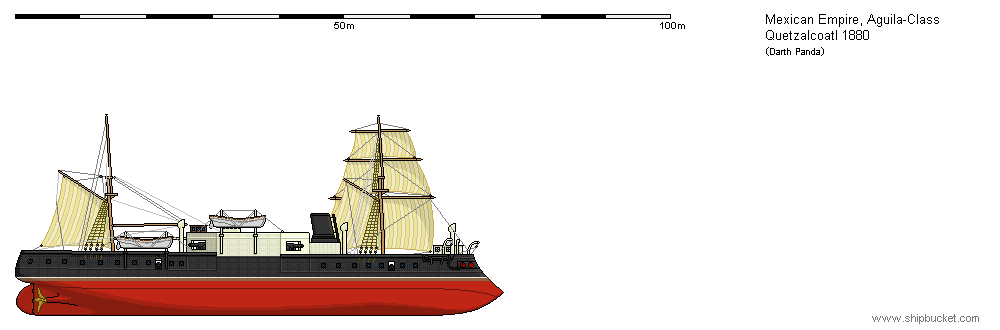

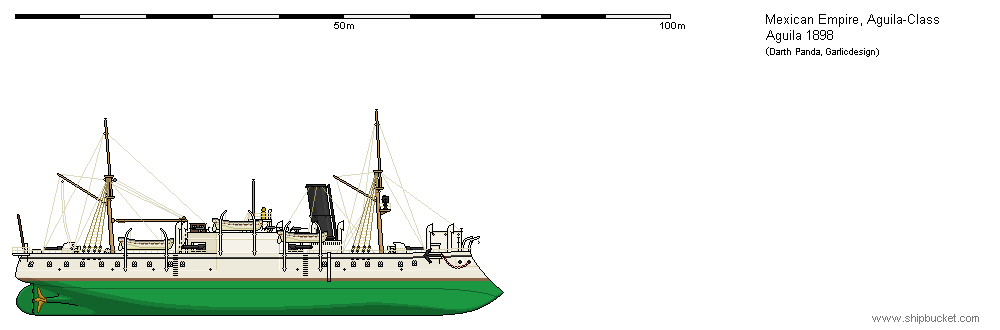

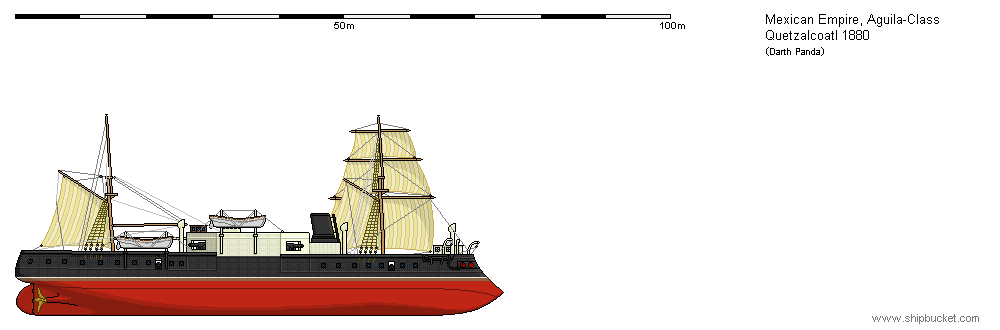

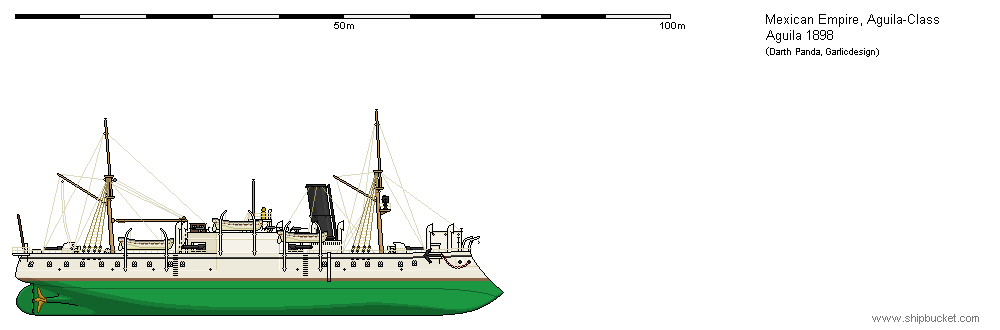

3. Aguila-Class

Originally ordered by the Ottoman Empire and built at the Samuda yard in Poplar/London, these ships were hastily purchased by the British government in 1878, when war with the Russians seemed imminent. After the war scare had subsided, they were considered surplus to requirements and put up for sale, and Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, then Mexico’s Minister of the Navy, was eager to acquire them. These ships were specifically designed as armored rams and thus were practically ideal for Tegetthoff’s favorite tactics. The contract was struck in 1880, and Belleisle (ex Peyk-i Sherif) was renamed Aguila (Eagle) for Mexican service, while Orion (ex Burj-i Zafer) was renamed Quetzalcoatl (pre-Christian Mexican deity).

Displacement:

4.870 ts mean, 5.400 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 74,50m, Beam 15,90m, Draught 5,35m mean, 6,40m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Horizontal Compound, 4 rectangular boilers, 4.050 ihp

Performance:

Speed 13 kts maximum, range 1.800 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

All wrought iron. Belt 305mm on 406mm wood; Ship ends 152mm on 254mm wood, battery 267mm around gun ports, 203mm sides; deck 76mm maximum, CT 229mm

Armament:

4x1 305mm/14 Armstrong RML, 4x1 100mm/21 Whitworth BL, 2x1 350mm torpedo launchers (forward, above water)

Crew

250

Quetzalcoatl was not yet completed when the deal was struck. Aguila crossed the Atlantic in July 1880; during her short service with the RN, her funnel was raised to reduce smoke interference. Quetzalcoatl followed in August 1882; as she was never commissioned with the RN, she retained the short funnel.

Despite excellent weather during the transit, both proved very lively and wet. By early 1883, both were fully worked up and formed the second division of the Imperial battle fleet, stationed at Veracruz. Both took part at the battle of Casimba during the Empire’s brief war against Spain in 1885; Aguila sank the Spanish ironclad Mendez Nunez, thus earning her place in naval history by being the last capital ship to sink another by purposeful ramming. After the Key-West-Incident of 1890, where Quetzalcoatl was present, but contributed little (her sister was under engine overhaul), both ships were taken in hand for rearming. Their 305mm muzzle loaders were replaced by 240/30 BL, the 100mm guns were landed and replaced by two 150mm/35 BL and six 47mm QF guns. The sailing rig was removed and they were reboilered with cylindrical boilers. Quetzalcoatl’s funnel was brought to the same height as Aguila’s.

The reconstruction did little to improve the poor seakeeping, and Quetzalcoatl was reduced to guard duty at Acapulco in 1895. Aguila was put in reserve in 1897 after the big turret ship Mexico emerged from her latest reconstruction, but reactivated for the Spanish war of 1898. She however missed the battles of Mayaguana and Santiago, guarding the Mexican base on Bermeja island instead. She was hulked in 1899 and scrapped in 1902. Quetzalcoatl however, disarmed in 1901, lingered as an accommodation hulk for the Mexican pacific fleet at Tolopobampo till she became leaky in 1913. She was scrapped in 1914.

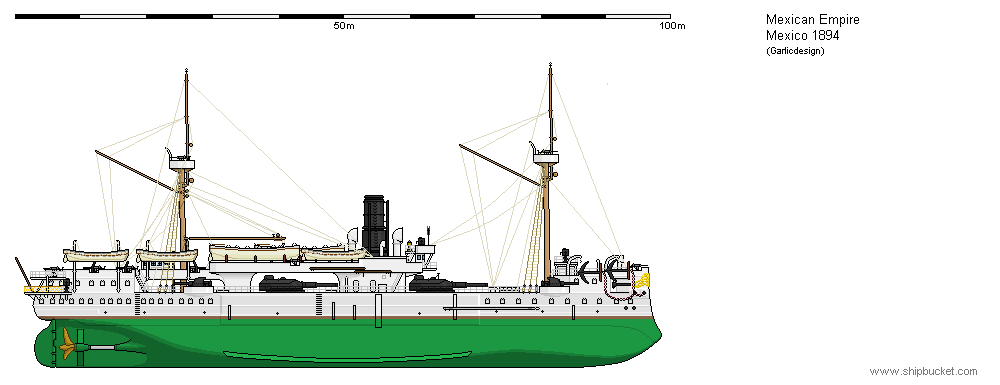

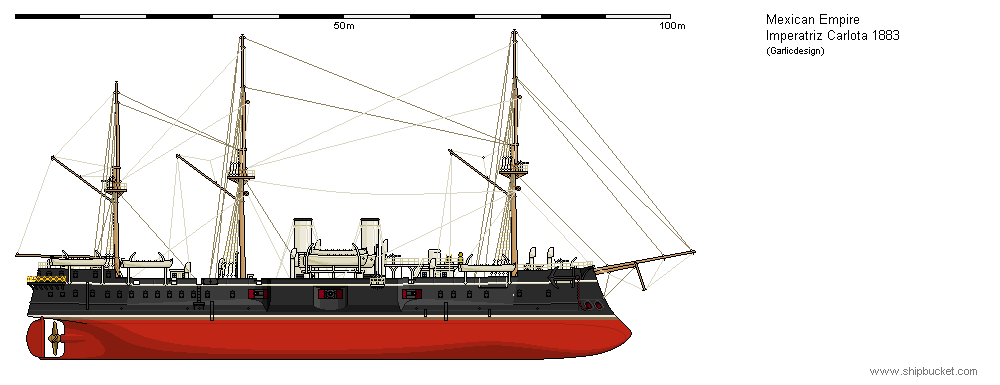

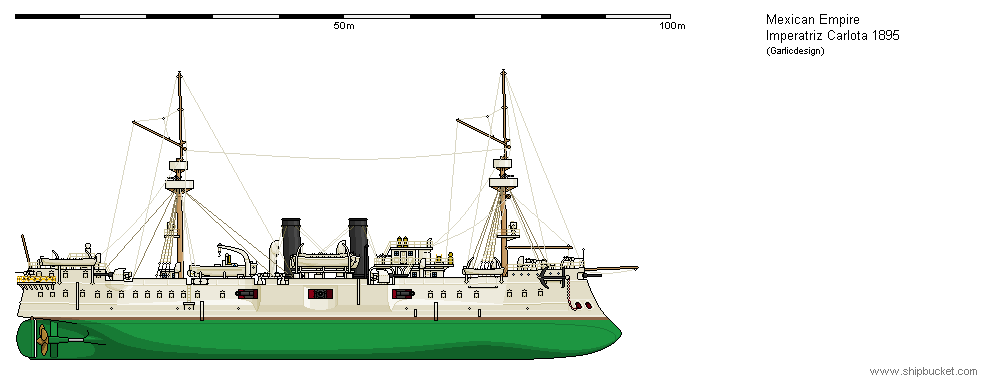

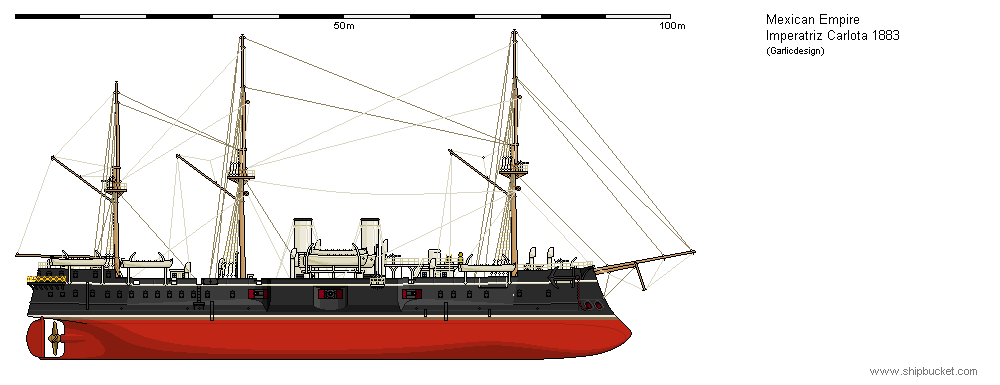

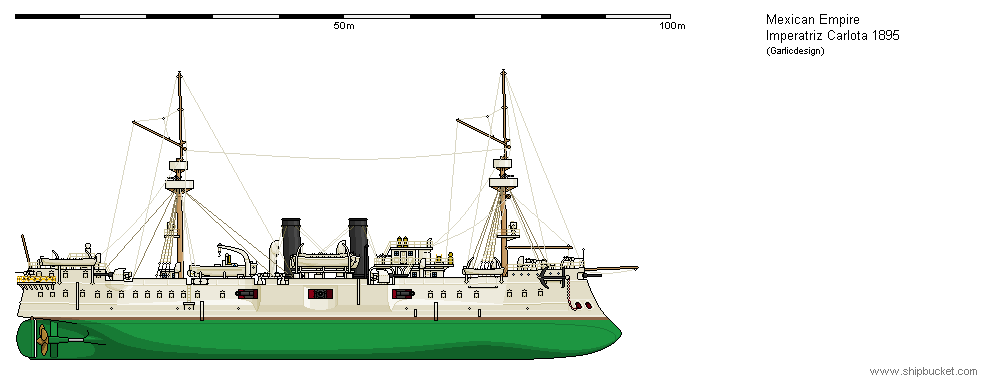

4. Imperatriz Carlota

The first seagoing ironclad built for the Mexican Imperial Navy, as opposed to ships originally built for other powers and later purchased by Mexico. She was carefully designed to specifications set by Tegetthoff himself and was widely considered one of the best central citadel ironclads ever built. Unlike many other – particularly French – central battery ships, the three heavy guns on each side of her casemate had mutually overlapping arcs of fire, while still providing two guns capable of firing dead ahead. She also had an unusually large protected area and was well strengthened for ramming. Her single-shaft machinery however was a drawback, resulting in insufficient maneuverability, especially for ramming tactics; her barque-style sailing rig was of little practical use. Imperatriz Carlota – named for the late wife of Emperor Maximilian – was laid down at Trieste in April 1876 and completed in October 1881. The long gestation period handsomely paid off in the high quality of her finish, and upon her arrival in Mexico after a midwinter Atlantic crossing early in 1882, she became the Imperial Navy’s flagship, relieving the bigger and more powerful, but rather unstable turret ship Mexico.

Displacement:

7.430 ts mean, 8.200 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 92,50m, Beam 21,80m, Draught 6,20m mean, 7,55m full load

Machinery:

1-shaft Horizontal Compound, 9 cylindrical boilers, 6.750 ihp

Performance:

Speed 14 kts maximum, range 3.000 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

All wrought iron. Belt 368mm on 254mm wood; Ship ends 330mm on 254mm wood, battery 370mm; deck 64mm maximum, CT 178mm

Armament:

6x1 280mm/20 Krupp BL, 6x1 87mm/22 Skoda BL, 2x1 350mm torpedo tubes (1 forward, 1 aft, above water)

Crew

525

She led the Mexican fleet during the First Spanish war in 1885 and the Key-West-incident of 1890, where her gunnery wreaked heavy damage to the yard-new cruiser USS Charleston. She formed the first division with Independencia in 1885 and with Rio Brazos in 1890.

In 1892, she was taken in hand for a very ambitious modernization. To improve speed and maneuverability, her entire machinery was gutted and a new twin-shaft VTE-plant with eight Belleville tube boilers was installed. Engine power was increased to 8.150 ihp and speed rose to 15,5 knots. She lost her sailing rig in favor of two military masts, and her bridge was substantially enlarged. Armament was also revamped; the 280mm guns were replaced with 240mm/35 Krupp BL with better ROF and range, and her light armament now consisted of five 150/35 Krupp BL, nine 47/44 Skoda QF and six 47/33 Hotchkiss revolvers. The torpedo tubes were retained, and complement increased to 575. She re-entered service in 1896.

Despite her obvious age, Imperatriz Carlota re-joined the active fleet, but was not re-integrated into the battle fleet. Instead, she was used for cadet training and made several far-reaching goodwill tours. She was in the Mediterranean when the Second Spanish war commenced and captured three Spanish Merchants, but when she returned to Pola for coaling, she was detained there for the remainder of the war. She also was in the Far East during the Boxer rebellion and added a hundred crewmembers and two landing guns to the international ‘rescue’ force. When she eventually returned home, she was placed in reserve in 1902, never to be re-commissioned. She was hulked in 1908 at Acapulco and remained there as a stationary guard ship. She survived the US-Mexican war of 1916, and due to her age and state was not demanded as a prize by the USA. She was disarmed and sold for scrap in 1920, but remained in use as a floating oil depot, in a similar way as HMS Warrior in the UK. Unlike Warrior however, she was not preserved, because her hull had become hopelessly rotten in 1940. She was scrapped in 1941, aged 60.

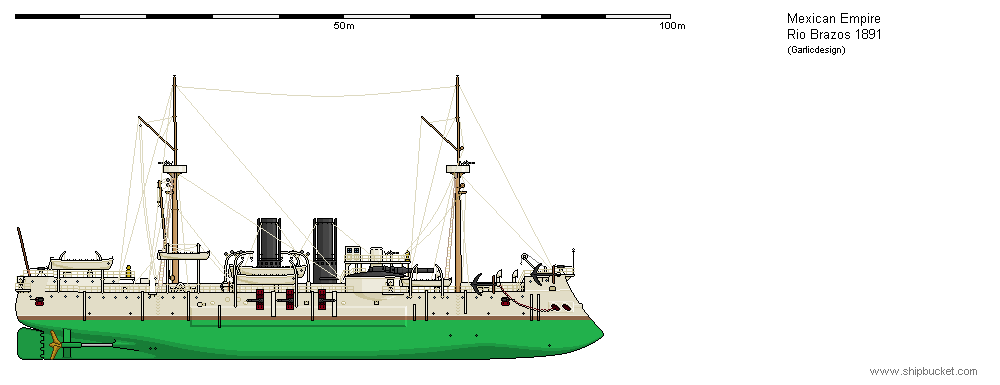

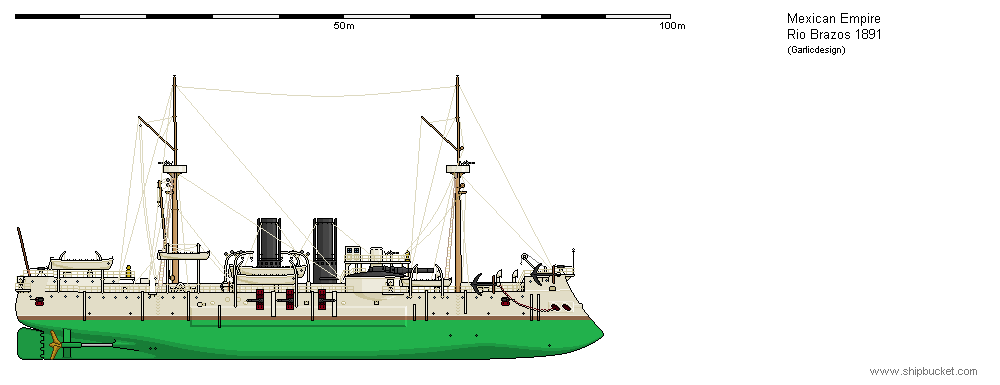

5. Rio Brazos

In 1884, the Austrian government ordered two battleships to the same specifications, one from their naval yard at Pola (becoming the Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf) and another at STT, becoming the Kronprinzessin Erzherzogin Stephanie. Under special permission of Emperor Maximilian, Tegetthoff was consulted during the design process. The result were ships optimized for ramming, with their 305mm main guns arranged in a way to provide more ahead firepower than was available on the broadside. Tegetthoff considered STT’s solution, which had the same protection, one less main gun, but stronger secondaries, also being smaller and faster, as superior and convinced the Emperor to order an identical clone in 1886. The ship was laid down in 1887 and transferred to Mexico in 1890, after having been built in 33 months, slightly more than half the time of the Austrian original. She was named for an indecisive naval engagement during the Texan war of Independence, which was re-defined to a victory by Mexican propaganda.

Displacement:

5.080 ts mean, 5.700 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 89,80m, Beam 17,10m, Draught 6,10m mean, 6,60m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Compound, 10 cylindrical boilers, 8.000 ihp

Performance:

Speed 17 kts maximum, range 2.400 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Compound. Belt 230mm; Ship ends unprotected, barbettes 280mm; deck 25mm, CT 50mm

Armament: