PLAN DOG: SYNOPSIS: THE KYUSHU PROBLEM, IT IS BETTER TO GIVE THAN TO RECEIVE.

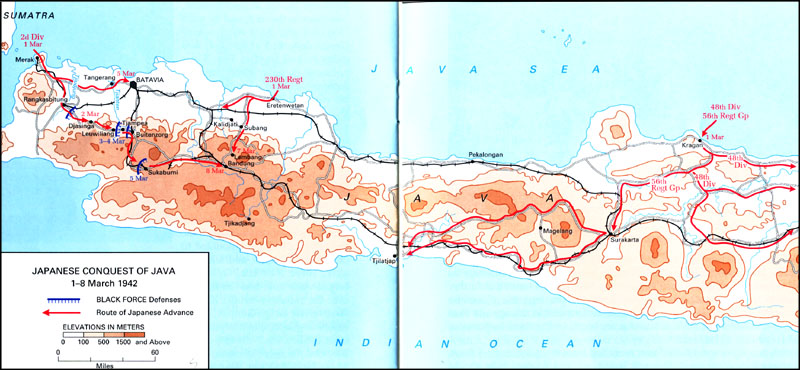

One of the things about Pearl Harbor that makes it so easy, is that the enemy (the USN) concentrates all the targets into a nice cramped harbor with one channel into and out of it. The Imperial Japanese Navy is another matter. There are two main base clusters in the target sets. One base cluster set is situated on Kyushu. That target set is distributed among three naval bases, one anchorage and two IJN and two IJA airbases in the distribution in 1931. (See map above.). It is not so easy to Port Arthur the Orange Team (the Imperial Japanese navy) in that kind of setup, especially with the projected area defenses in place as indicated.

The biggest problem is air coverage. Those airpower circles show what the Japanese 1931 aviation can actually cover. That includes their excellent Nakajima B1M and B2M with reported ranges of ~ 1200 kilometers. The rough rule of thumb, divide by three to get the combat radius, only works for post 1935 aircraft. For a patroller, pre 1935, the rule is air hours at cruise, then divide the result by 4. The average combat patrol radius for Japanese and American aircraft is about 160 kilometers or 100 statute miles. So guess where Admiral Harry Edward Yarnell (TF 10.1 Actual) has to approach with his fleet to do the dirty deed to Kyushu?

If one guesses about 50 kilometers southeast of Fukue Island, then give oneself a cigar. This is the only seam and gap in the 1931 air defense coverage that protects Kyushu. It also happens to be smack in the middle of the commercial sealanes that cargo ships use to carry oil and foodstuffs from south-east Asia and Dutch Indonesia to southern Japanese ports. Two major Japanese airbases in the Rykuku Islands at Futemna and Kodema (Okinawa), make for further extreme difficulties. Nevertheless. American task forces have gamed this type of operation out as the “Orange Team” against both the Blue Team land-based air, surface fleets and opposing alerted “enemy” aircraft carrier forces in previous wargames. The conclusion the Orange Team gains? Aircraft carriers can approach to within 100 kilometers of an enemy coast and deliver a surprise air raid. The attacker runs the risk of losing many aircraft (about half of the attackers) and up to half of the attacking aircraft carriers can be sunk, but the defender usually suffers twice the losses. If the attacker achieves complete surprise, he can inflict substantial damage and escape almost unscathed. He has to strike and run though. If he hangs around to enjoy the fireworks, he becomes submarine bait. The basis for these conclusions is a series of 1920s exercises begun in 1923 (RTL) to work out the peculiarities of the aircraft carrier as a fleet scout. It turns out (in this AU it is the Lincoln Canal and Pearl Harbor. In the RTL it is the Panama Canal and Pearl Harbor.), that the pesky scouting force commanders in these exercises are more interested in attacking the Lincoln (Nicaragua) Canal and/or the Blue Team ships moored in their harbors. In fact, no less than five times is Pearl Harbor or the Panama Canal bombed. After Admiral Yarnell “sinks” three battleships at their moorings in Fleet Problem 12, Charles Adams, Hoover's navy secretary, who observes the Blue Team fiasco, throws his hands up in disgust and exclaims to Admiral Schofield (Chino Actual), “Why do we even bother with defense at all?”

THE NATURE OF THE (AIR) BEAST.

Japan has two competing (emphasis on the word competing) air forces. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) has a circus act based on Imperial German Army WW I practice, which is odd, since the Japanese army air service is taught how to fly by the FRENCH. The IJAAS organization is more or less two squadrons of 9 planes each, a 3 plane reserve section and a 3 plane headquarters element; 24 planes in total. Two squadrons form an air battalion, (50-54 planes) two battalions form a regiment (100-120 planes); two or more regiments form a division (200-250 planes, depending on types) and two or more divisions form an air corps. (~500 aircraft) The IJAAS has two of them, air corps that is. One (~600 aircraft) is in China fighting

the Mukden Incident, and the other corps (training force of ~450 machines) is in Japan, where it ostensibly provides part of the home islands defense. This is good news for the USN. IJAAS pilots in Japan are mostly trained for close air support with the IJA fighting in China. They have second rate machines for a training establishment and a military mindset totally unsuited for naval warfare or for strategic air defense. They are trench strafers. The Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service (IJNAS) considers them useless and so treats the IJAAS.

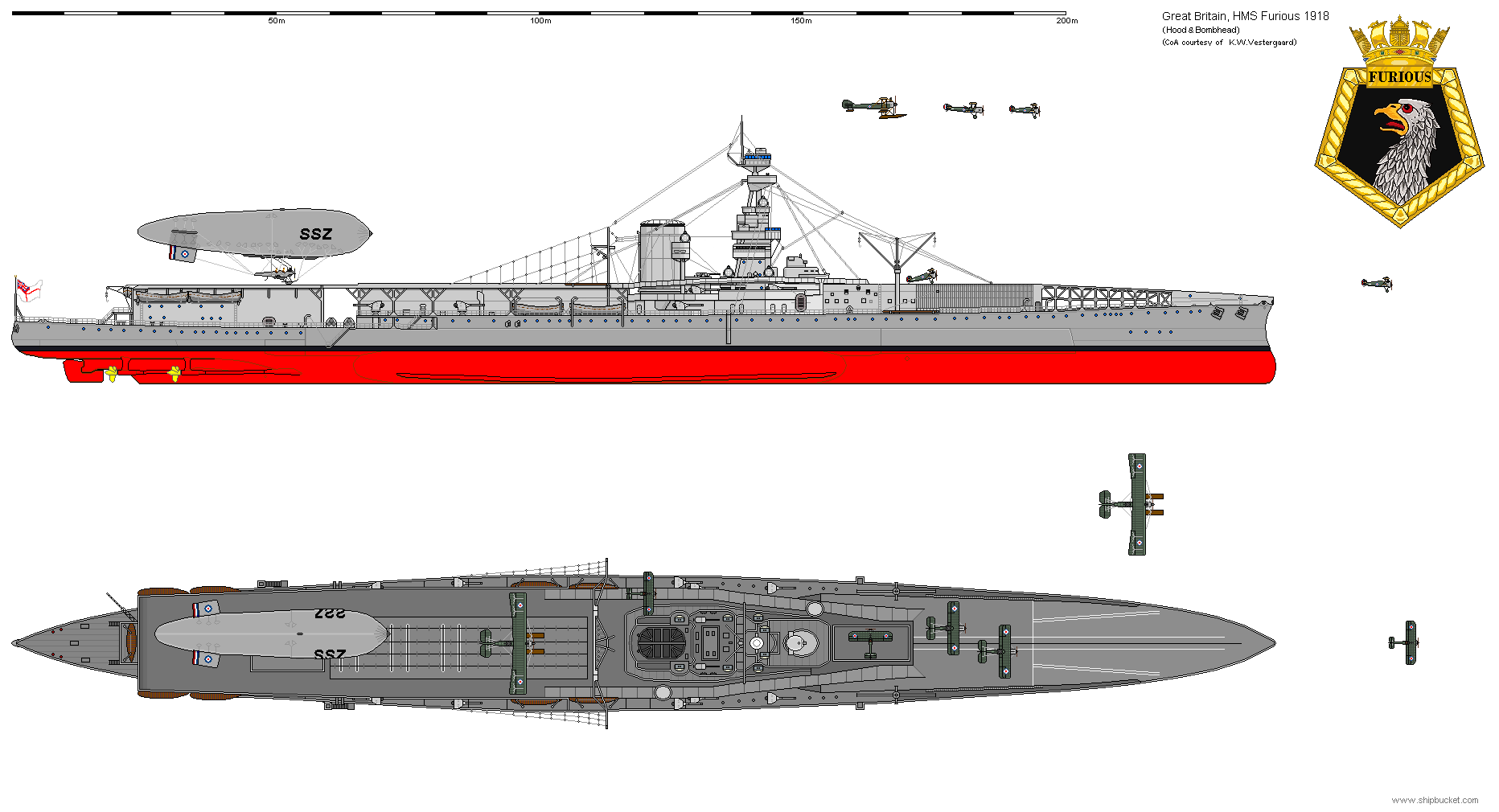

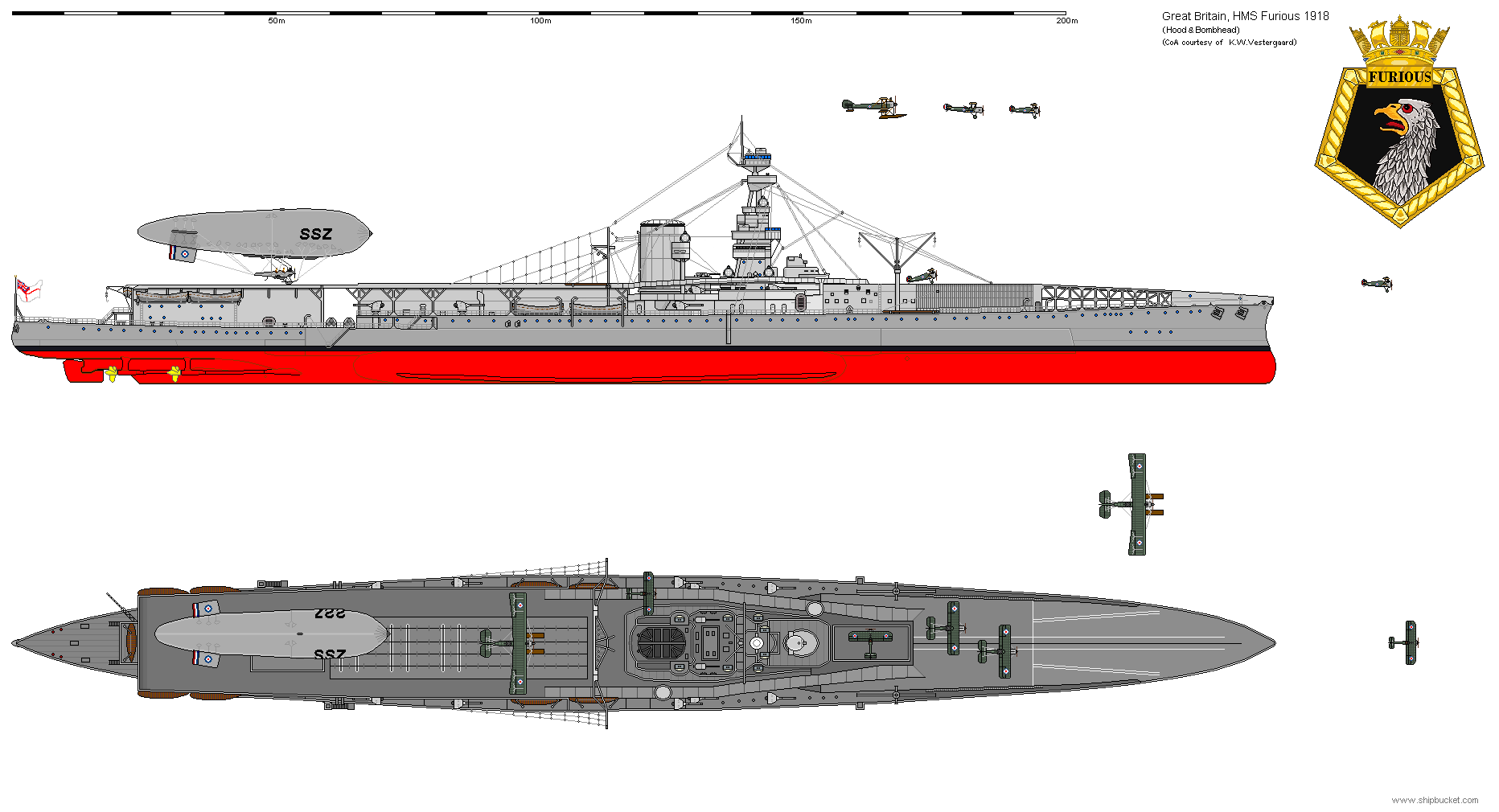

The IJNAS is another beast of a different order. British equipped, Royal Navy indoctrinated and trained, they are a tough bunch of honchos, the cream of the Japanese Navy which already gets Japan’s best,

and they know it. Organizationally, outside the carrier air groups, the IJNAS (11th Fleet is the land based headquarters command for non-ship borne INNAS aviation), the IJNAS builds on an airbase ground unit called a squadron (hikotai) composed of four subunits called Shotai (3-4 aircraft section that forms a 12-16 aircraft squadron + 4 reserves for the leadership). These Hokutai might be grouped into 2-4 squadrons together to form a Group (~24-60 aircraft). That is the baseline unit for the 11th Fleet. By 1931 there are five embarked groups on Japan’s carriers (~260 aircraft total, a roughly split in half force of torpedo bombers and scout fighters). The 11th Fleet operates 40 groups of land based aircraft, or roughly 1600 aircraft, of which 200 are seaplanes of all types, about 400 trainers and a mixed force of 1000 aircraft split in half between pure fighters and scout fighter/light bombers. The bombers, are mostly an odd job assortment of the usual twin engine biplanes one sees for the era and one Special Group of heavy bombers which are functionally akin in purpose to the British Vickers Vimy or the American Keystone LB-7 (B-3 and B-6) equipped bombardment groups, used exclusively as pure terror weapons. (The Mitsubishi Ki-20 is based on the German Junkers G-38. It is a deathtrap.) Unfortunately this Special Heavy Bomber Group (特別な衝突のグループ) of 6 planes is based at Atsuga airbase, a fact which Admiral Henry Varnum Butler (TF 10.2 Actual), will discover the hard way as he raids Yokusuka.

WHAT ABOUT THE BLUE TEAM?

The AU USNAS, is an all-Navy show. Even so, though the idea is to obtain unity of purpose as well as unity of command; it is almost as screwed up as the Japanese command setup is. There is Carrier Aviation otherwise known as the United States Navy Air Battle Force (USNABF), Ship-borne Scout Aviation known officially as the United States Navy Forces Afloat Scout Force (USNFASF), Maritime Patrol (USNMP), Homeland/Base Air Defense Aviation (USNBADA), Tactical Aviation (USNTA), Strategic Aviation (USNSA), and the Army Support Service (ASS), the United States Navy Air Transport Service (USNATS), and the Marines off in their corner, running their own United States Marine Corps Aviation (USMCA). Just plowing through the acronyms is acrimonious. Whatever acronym the naval aviator finds himself under, he will be part of a two plane section, that forms a four plane element that forms an eight plane flight that forms a squadron of sixteen planes. Reserves and replacements for squadron operational losses come from central force pools (Group level or higher) Groups on carriers are two to four squadrons+flights (~24-64 aircraft per carrier). Groups ashore are based on plane type (administrative and logistics simplification). Bomber Groups are ~32 aircraft. Fighter groups are ~ 64 aircraft. Seaplanes carried as spotters and recon scouts are administratively carried as assigned to the ship, like another piece of artillery or fire control gear; though a cruiser division that operates together will form an aviation section or flight. Flying boats, shore-based, are treated exactly like bombers organizationally and operationally , even if they are forward deployed and tender supported. This is one thing the USN gets correct. Those Boeing flying boats will come in handy during the Battle of the Volcano Islands.

So what does Congress authorize for the USNAS? The carrier aviation is usually the cream of the crop, both with planes and pilots. Officially the (RTL numbers ~260 aircraft for the actual 5 USN carriers extrapolated to the 9 AU carriers) is supposed to have ~ 360 aircraft on the 6 combat carriers and the 3 training carriers. The numbers fluctuate. The USN has this nasty habit of sending the carriers to sea to support the Marines in the South American banana wars and the seas down there can get rough. Usually about 40 aviators (RTL) a year DIE just in trying to land on the flattops. The aircraft, of course are destroyed too. This is one explanation for the small batch lots that Douglas, Martin, Curtiss, and Boeing manufacture during the 1920s and 1930s and why so many different types proliferate. If one thinks the land-based guys have it any better, then one has not heard of the annihilation of the USN’s lighter than air fleet through operational evolutions in tornadoes and flying weather that should have grounded fixed wing aviation.

Speaking of the RTL joys of American land based air? The Keystone LB-7 (B-6) is notorious as a pilot killer during the 1934 RTL Army air mail scandal. There is no truth to the assertion that the pilots who fly it, call it either the “Tombstone” or the “Headstone”.

Anyway… Congress, in its wisdom, authorizes 4 seaplane groups (~ 128 planes), 2 flying boat groups (~32 planes), 10 fighter groups (~480 planes), 3 bomber groups (~ 96 planes), 4 transport groups (~96 planes), 2 Marine Aviation groups (~100 planes) and ~100 scout observation planes to the fleet. There are 6 training groups, for Congress knows that in time of war, the need for pilots will skyrocket. (~192 planes, HAH!), for about 1224 planes ashore, which when added to the carrier aviation, that is about 1,584 aircraft AU (and RTL), authorized. Based on RTL readiness rates and availability, casualties in men and machines and the difference between what Congress will authorize and what it funds, the numbers are a lot closer to 700 aircraft, with the carriers getting the most money, men and machines. This means a front loaded war for Blue against Orange in 1931. It has to be fought that way, If Blue is outnumbered 4-3 in ships, 10-1 in deployable troops and

4-1 in the air. PLAN DOG is a recognition

that far from being in a position of inferiority as is supposed; for Orange in 1931, the chances for a Pacific knockout against Blue are the best chances that Orange will ever have. After 1932, the odds climb exponentially. Roosevelt will add 100 ships and triple the air forces by 1938. From 1938-1941

he will double it again.

HOW ABOUT SOME SUBMARINES TO GO WITH THE AIR RAIDS WE FEED YOU?

Congress loves Marines. And Congress loves Sub-marines. It never occurs to the Congress-critters that kilogram for kilogram and man for man, a submarine is twice as expensive as a battleship. But then again, if it is used properly^1, the submarine will kill ten times as many men and

twenty times as much shipping as any other class of warship. That includes aircraft carriers… especially aircraft carriers. RTL proof you ask? 12,850,815 gross tons is the accepted losses to U-boats for WW I.

How much tonnage was lost at Jutland? 105,000 tonnes by the British? Maybe 200,000 tonnes in surface actions during the war? We could look at US submarine numbers for WW II and ask the numbers. The Japanese lose 1,178 merchant ships for a total of 5,053,491 tons. The warship losses to US boats are 214 Japanese ships and submarines totaling 577,626 tons. A staggering five million, six hundred thirty one thousand, one hundred seventeen tons, (5,631,117 tons), 1,392 ships total.^2

How does American carrier aviation do? Depends. The numbers seem to skew badly in their favor. The flyboys sink 161 warships (711,265 tons), 359 merchantmen (1,390,241 tons) for a grand total of 520 ships and 2,101,477 tons. Most of those sinkings, however, are in-harbor sitting duck at their moorings ship kills in the final months of the war when the IJN and merchant fleet is forced to homeport for lack of fuel. (courtesy of the US submarine fleet hunting for tankers during the murderous year of 1944.^3)

The thing to which one should pay attention in this AU is that the Americans start out as competent submariners. They do not have the dud captains, dud torpedoes problems of 1941 in 1931. What they have is too few subs. They could use about forty more fleet boats (Type 171s) instead of the thirty or so Type 181s they will get in the 1931 AU emergency program. Using the rule of 1/3 for submarines rotated into combat, leaving combat and in combat, a 67 boat fleet that loses 6 boats in the opening operation of the war will be only able to keep 20 boats on station assigned kill boxes around and near Japan.

Operation Kettledrum uses about 12-20 U-boats (Type VII and Type IX) to sink almost 2.5 million tons of shipping off the US east coast in 1942. In 1931, the Japanese have just 3.2 million tons of own flagged merchant shipping. The postulated US Type 171s and the Type 181s use snorts and Type II Sargo batteries^4. The Japanese in 1931 are no better at ASW than they will be in 1944. Dead meat that is.

^1 The Germans kill 14,500,000 tons of allied shipping in WW II. Apparently they use U-boats well in the beginning for a while.

^2 The Americans take 2 years to figure out how. Most of their kills come in 1944. The Americans are slow learners.

^3 Does anyone mourn for the ~40,000 men the Silent Service drowns? One must remember that this kind of war is

unspeakably awful.

^4 Friedman, Norman (1995) U.S. Submarines through 1945 Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-263-3, p. 336. The Italians beat the Dutch to it by ten years ( Capt. Pericle Ferretti 1926 for the Sirena class.). In the AU the USN gets wind of it and adapts the Sirena system to replace their own R-boat snorkels which have not been working.