Hello again!

Hawker Siddeley P.1126 Hurricane II

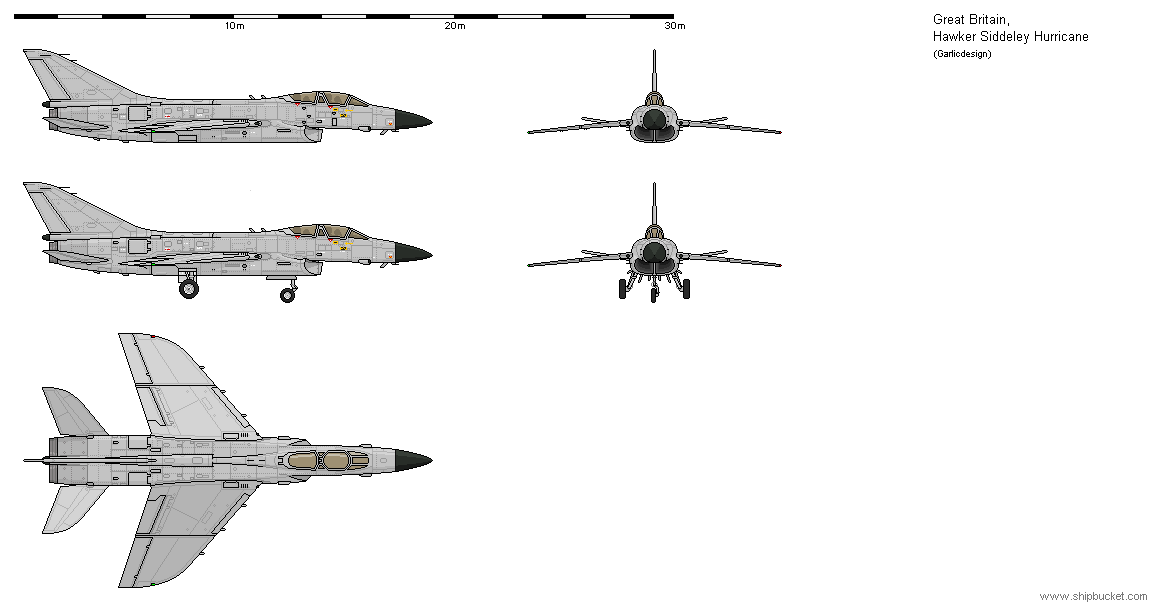

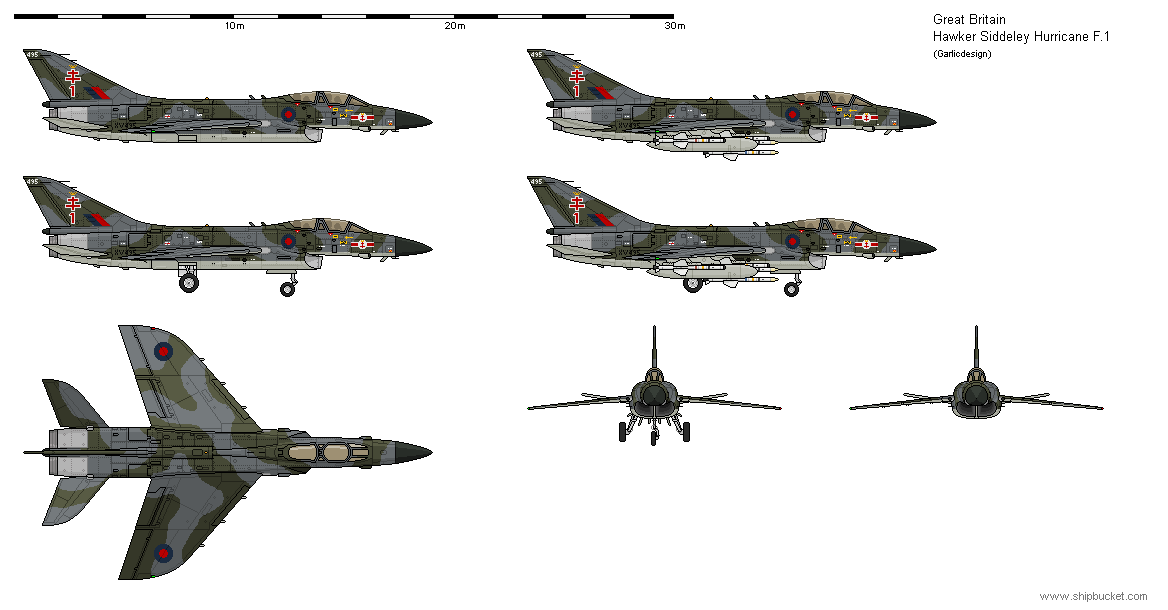

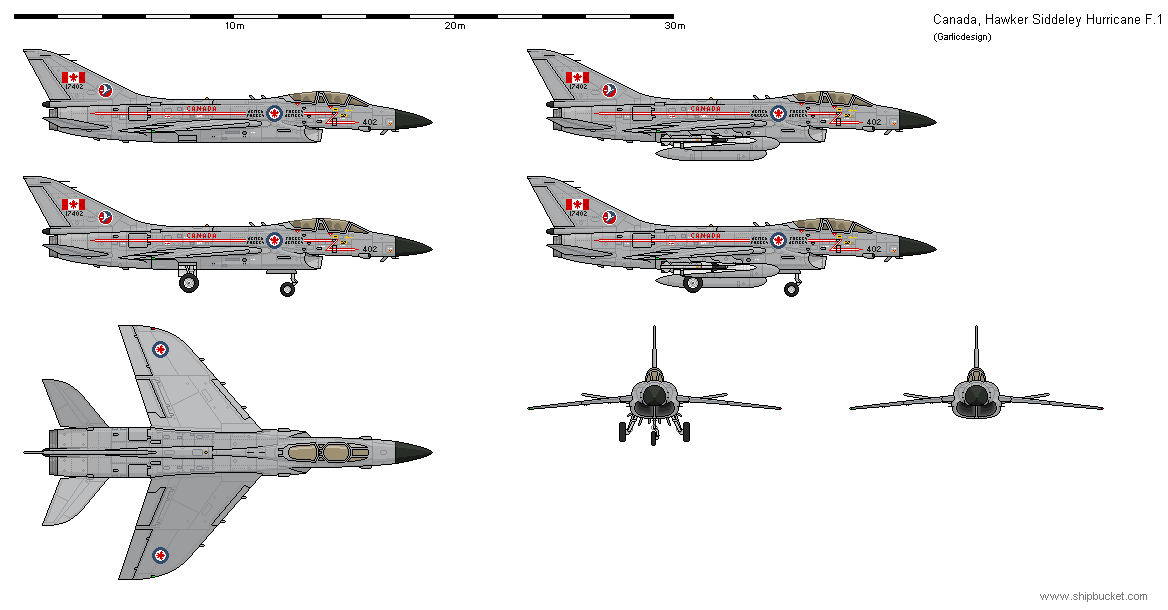

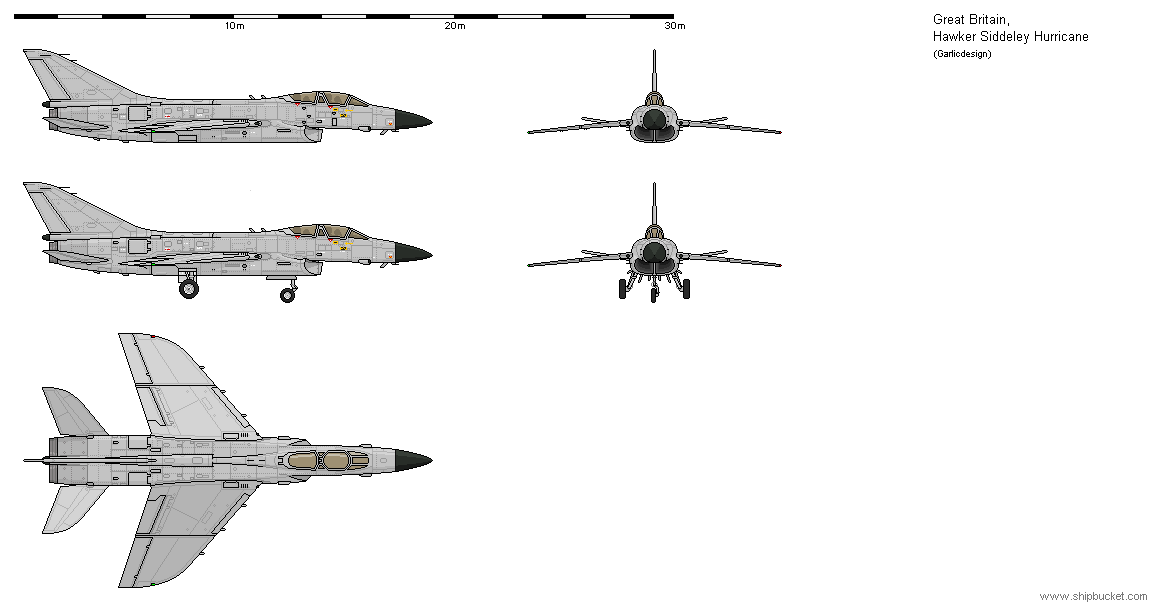

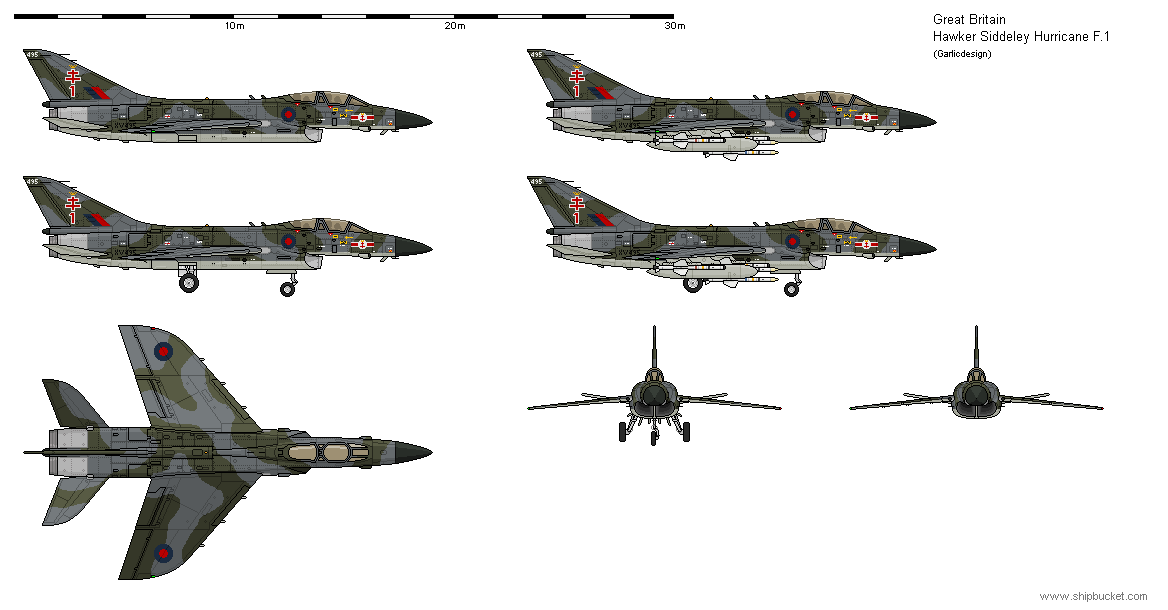

During the late 1950s, Hawker Siddeley had submitted the single engine P.1103 and P.1121 and the twin-engine P.1125 and P.1129 designs, which all resembled each other to some degree, for various RAF requirements and always been turned down in favour of less conventional, more futuristic looking and in some cases outrightly unrealistic contenders… all of which ultimately failed. At about the same time, Avro Canada, at that time 100% owned by Hawker Siddeley, was threatened by collapse after the cancellation of the huge Arrow long-range interceptor. While Hawker Siddeley moved on to designing VTOL airplanes in the 1960s, Avro Canada launched a last ditch effort to develop the P.1121/1129 into something useful. Canada’s 1959 decision to contribute nuclear-tipped Bomarc missiles to NORAD and loaning obsolescent F-101 interceptors was highly unpopular; the US themselves ditched Bomarc as unsatisfactory just at the time the first Canadian battery became operational, and all the development money was blown. The resulting scandal led to the fall of Canada’s government in 1963. By that time, Avro Canada was able to present a prototype of a downsized P.1129 with two reheated Gyron Junior engines. The twin-seat machine was dubbed P.1126 by the mother company although half the design work had been done in Canada. The machine was shorter and lighter than the original P.1121, but had the same wings, resulting in low wing load and surprisingly good agility for a 1960s design. A valuable feature carried over from Sydney Camm’s original P.1121 was the robust and durable structure. The P.1126 also retained the large internal fuel capacity of the P.1121, both in the hull and the wings, and had no less than five wet hard points for additional auxiliary fuel tanks, in order to satisfy the RCAF’s requirement for very long range and large radius of action. If four fuel tanks were carried, four Sparrow and two Sidewinder missiles could be installed, and the advanced fire-control system provided for various other armaments – including the upcoming AIM-47 AAM – and was rigged for integration into NORAD’s SAGE control system. Unusually for a 1960s fighter, the P.1126 was designed to mount two 30mm Aden cannon in the wing roots, which was however an optional feature. The only weak points were the engines, which were rather unreliable and somewhat underpowered for the size and weight of the airframe, but this weakness did not stop the plane’s first flight in February 1963 from becoming a great success. Even with the Gyron Juniors, the P.1126 was faster than the F-101B, and there was no other contemporary interceptor with such great flight characteristics; it was described as both nimble and good-natured, able to roll the intercept and air superiority roles into the same airframe. The RCAF was immediately interested in the P.1126, and as flight testing progressed, the RAF also realized the gaping requirement it had for just such a plane to replace its current generation of subsonic all-weather Javelin and Sea Vixen interceptors. Having nearly destroyed their aviation industry by a string of project cancellations, HM government realized that P.1126 was about the last chance for an all-British high performance jet fighter to be built in Great Britain and thrown onto the world market. As much of the development cost had already been spent on preceding projects, it was to be had at a reasonably competitive price. Both factors appealed to the unions and the current labour government. There even was a solution for the engine problem in the shape of the brand-new Spey turbofan, which was due to enter service in the Buccaneer S.2 in 1964. That engine could be easily modified with an afterburner for half again the thrust of the Gyron Junior, and the burner variant indeed had its first test run in mid-1964. Late in 1963, a pre-series of 20 machines with reheated Spey engines was ordered for the RCAF, the RAF and the RN (4+10+6). The first Spey-powered P.1126 flew in October 1964. The plane accelerated to Mach 2 on its maiden flight and was much superior in every respect to the prototype; with the Spey engine, the P.1126 was equal to the F-4 in every respect. In December 1964, a total of 240 units was ordered (160 for the RAF and 80 for the RCAF), and the P.1126 was officially dubbed Hurricane II, to honour Camm’s war-winning masterpiece.

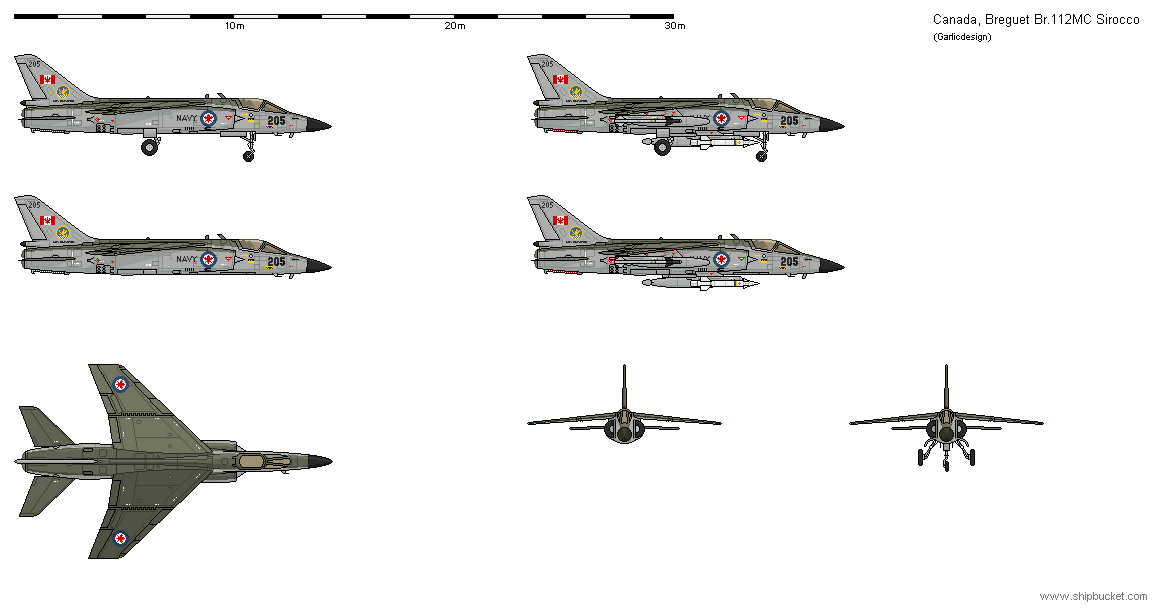

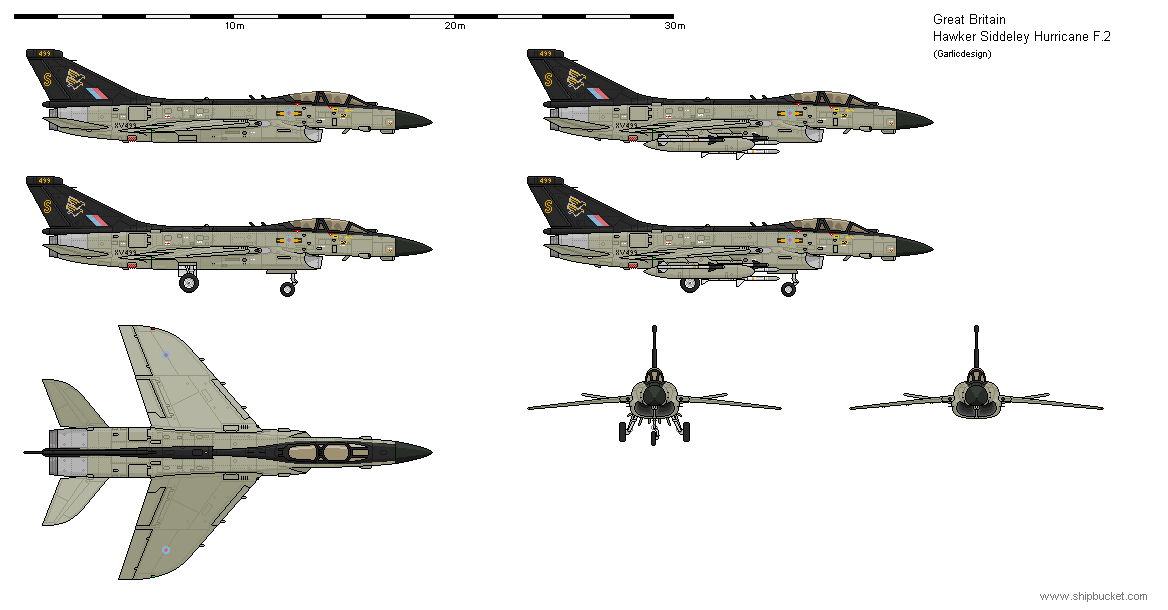

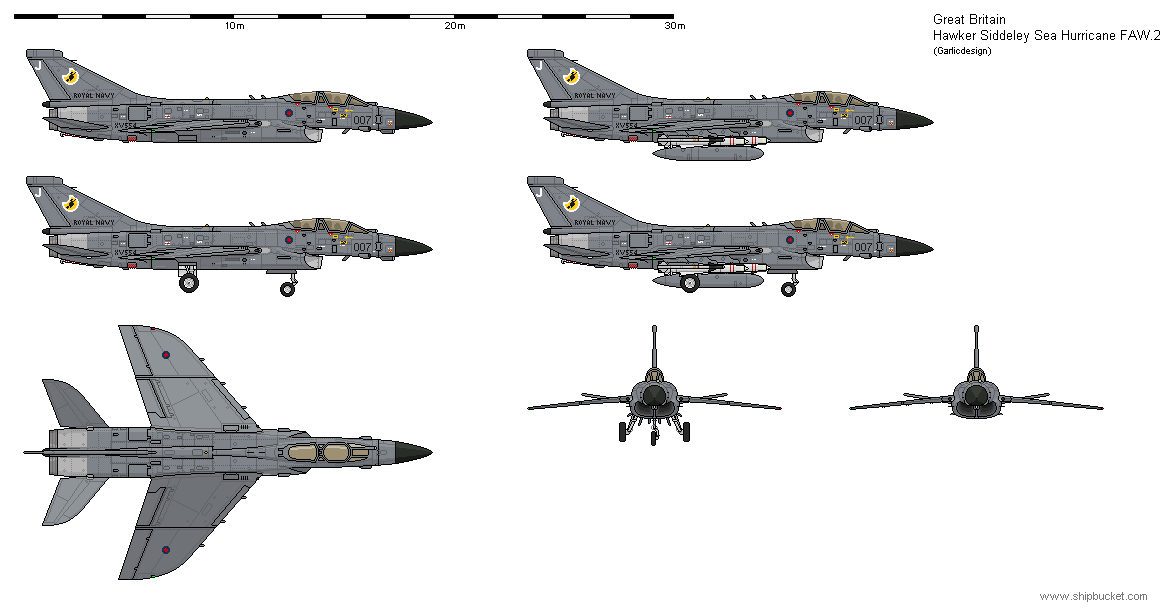

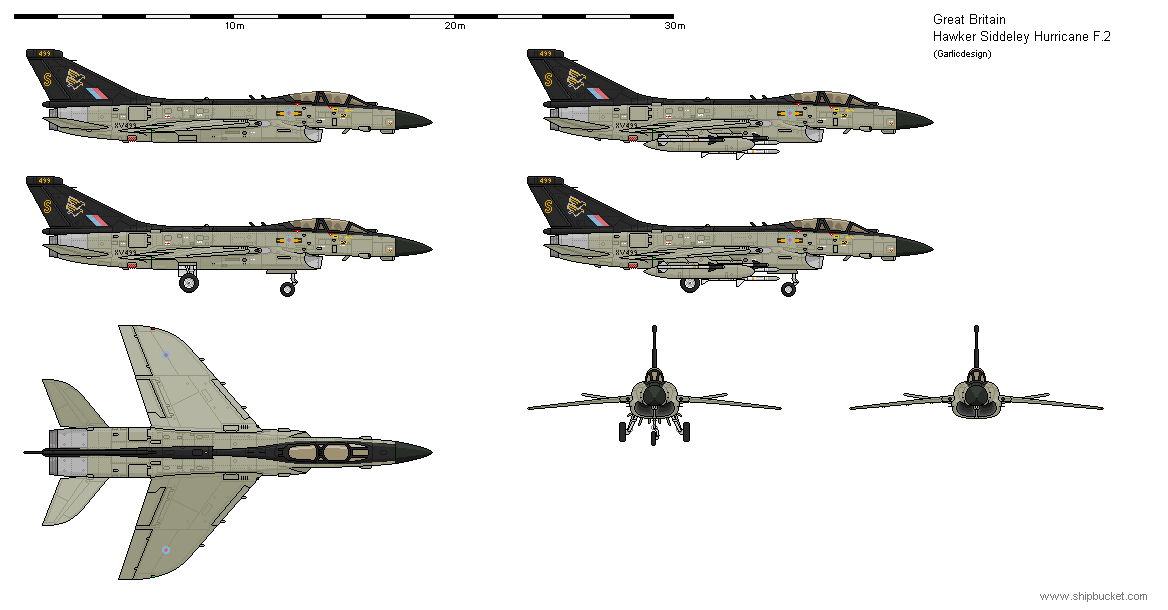

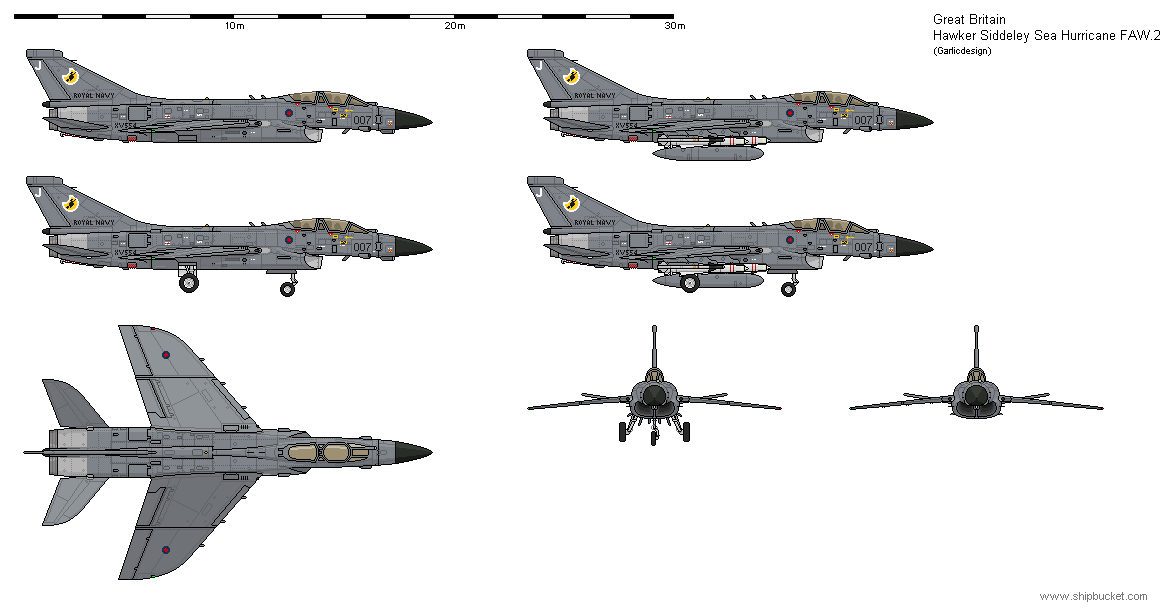

While series production was set up (the plane was to be built independently both in Canada and Great Britain), testing of the naval version proceeded. It needed ailerons and blown flaps to achieve the necessary slow landing speeds, and the foldable wing and nose section also added weight. It took Hawker Siddeley till late 1965 to fully navalize the Hurricane (the last Sea Hurricane pre-series machine first flew in November that year. Compared to the land version, the Sea Hurricane was slower (Mach 1.8 at ideal height instead of Mach 2.0 for the land version) and had somewhat less range; it also lacked any installations for the secondary air-to-ground capability later built into the land Hurricanes. Of the RN’s current generation of carriers, only HMS Gibraltar had no problems handling a plane of this size, while Ark Royal and Eagle would need either considerable refit or – ideally – replacement; this issue was solved with the left-swing of Thiaria’s government in 1966, which threatened both Cape routes and was cited as the main reason for the go-ahead for three CVA-01 carriers in mid-1966. By that time, the RAF and the RCAF were commissioning their first series Hurricanes. The RAF machines replaced the Javelin all-weather fighters and were armed with up to eight Red Top missiles; a version of the Red top with SARH guidance and twice the range of the IR version had become available in 1965, and the Hurricane typically carried four of each version (two each of the radar variant at the sides and below the fuselage, and the four IR guided missiles under the wings). No guns were initially carried. By 1968, the RAF had 120 Hurricanes in service.

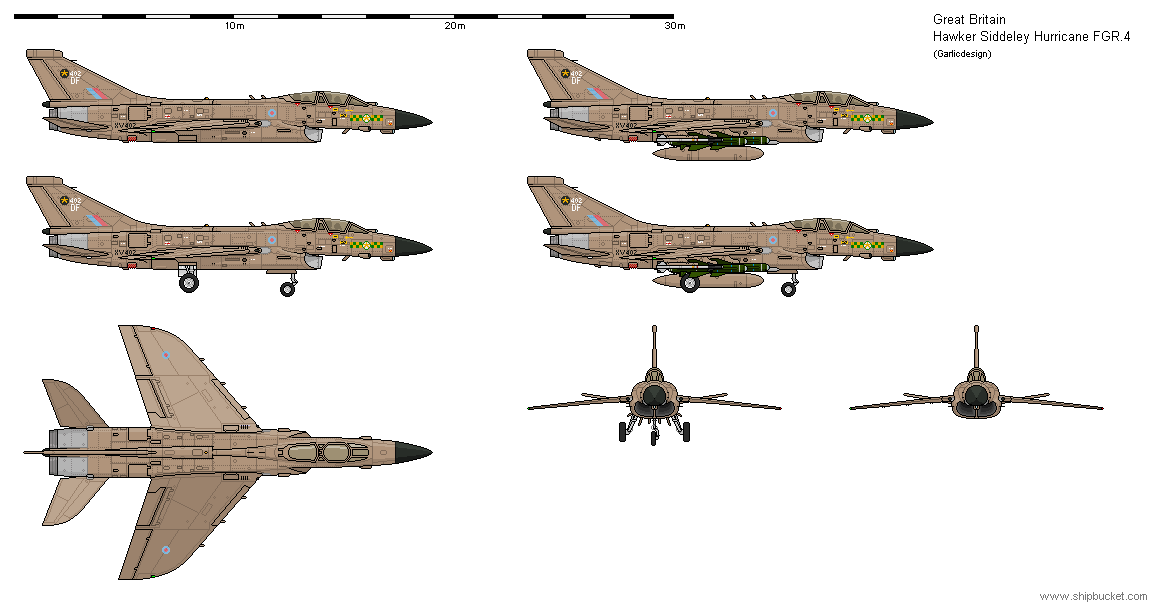

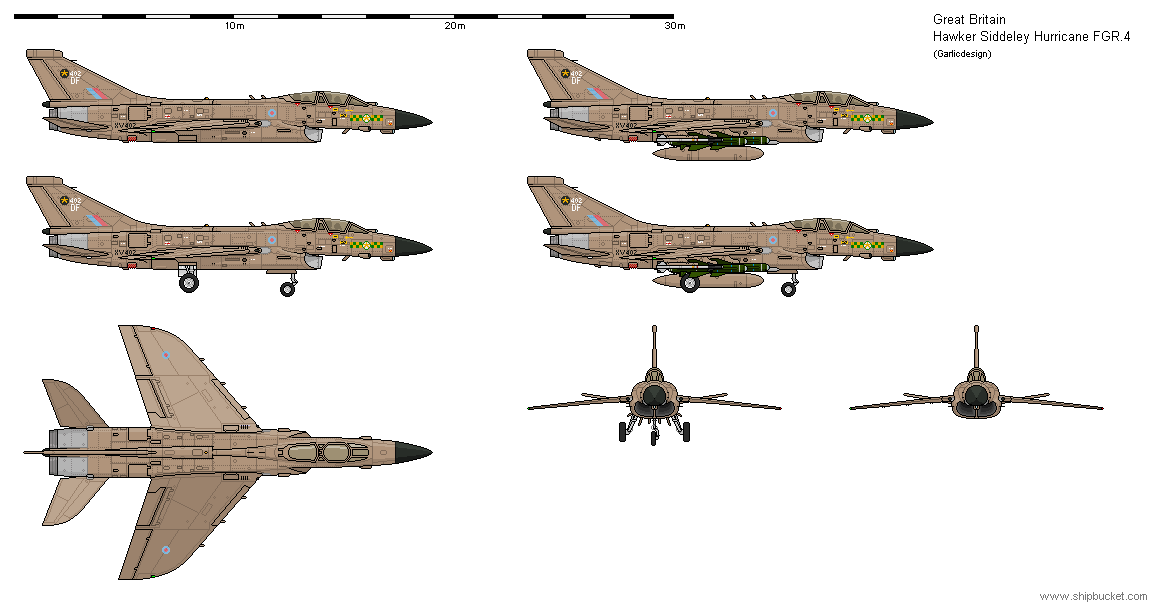

The last 40 RAF machines were completed with two 30mm cannon each, bombsights, low level navigation aids and strengthened hard points for air-to-ground use, but retained their full air-to-air capacity; they could carry seven tons of ordnance. This FGR.1 version was subject of a repeat order over 40 machines in 1968, which were delivered by late 1970, bringing the RAF total to 200.

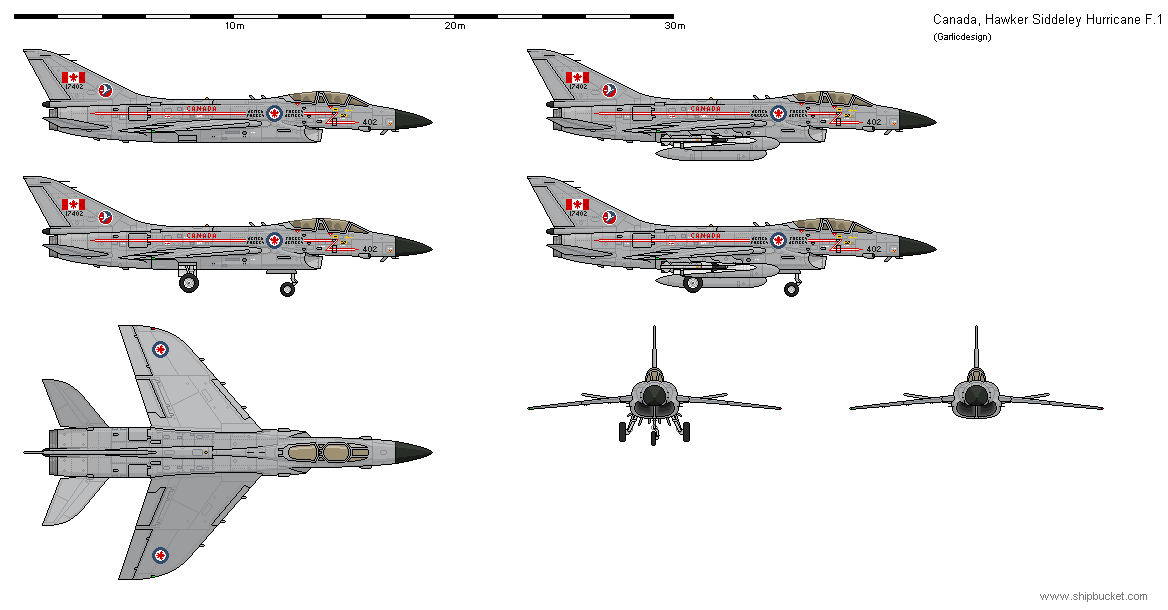

The RCAF armed its Hurricanes with a mix of Sidewinder, Sparrow and AIM-47 Falcon missiles, the latter with conventional warheads; gun armament was initially omitted. The loaned F-101Bs were returned to the USAF in 1966/7 (which re-sold them to the Iranians). Deliveries of 80 units were complete in 1968.

The Sea Hurricane FAW.1 entered series production in mid-1967, carrying the same armament as the Air Force machines; they had the 30mm cannon installed from the start. A total of 100 machines to equip four carrier air wings with 15 interceptors each, plus an OCU and some reserves, was delivered till late 1969. They achieved FOC on HMS Gibraltar in late 1968 and also flew from HMS Ark Royal and HMS Eagle, which barely were able to operate ten each after some half-assed modifications. The three old carriers were intensively used to train the new Sea Hurricane squadrons, and when CVA-01 (HMS Queen Elizabeth), CVA-02 (HMS Duke of Edinburgh) and CVA-03 (HMS Prince of Wales) were commissioned in 1972, 1974 and 1977, respectively, the Hurricanes only needed to move in.

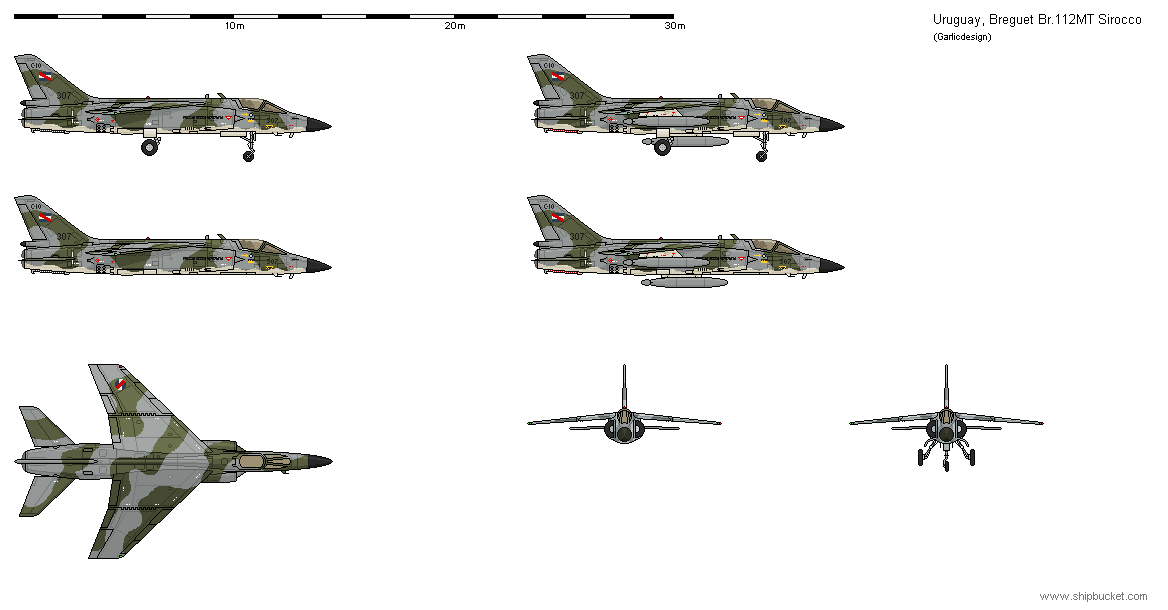

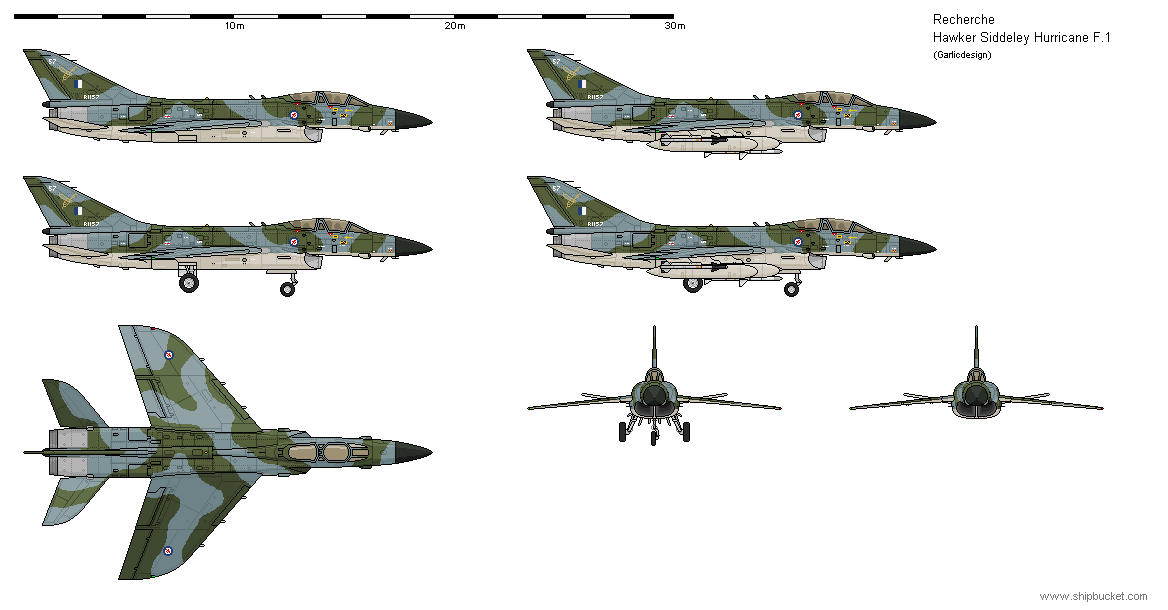

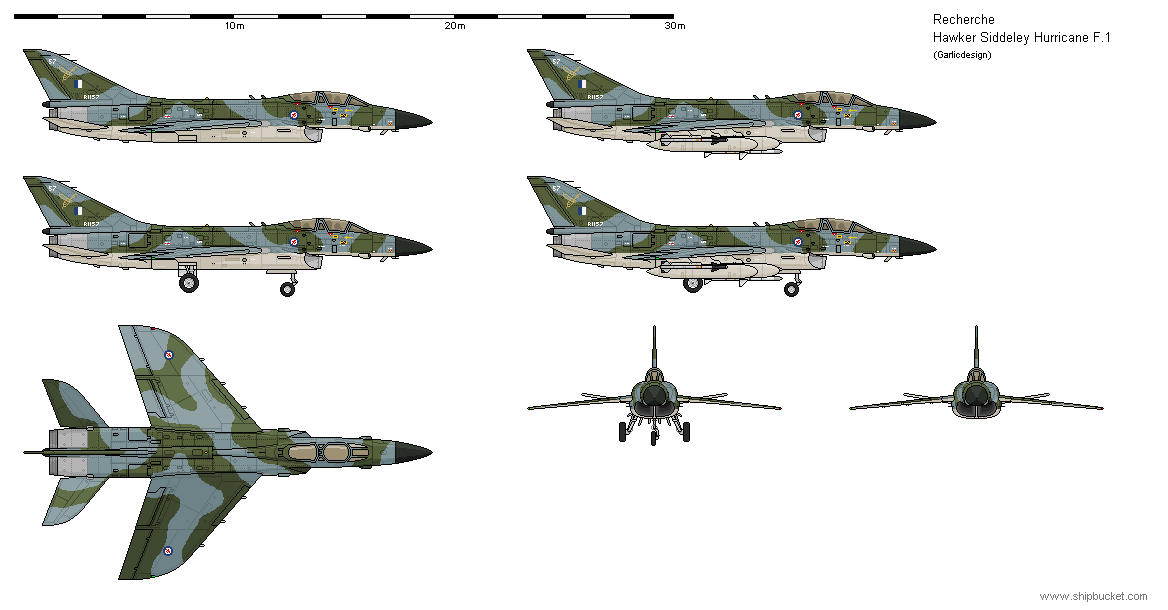

With its combination of range and all-weather firepower, the Hurricane was mainly attractive for countries with large land or sea areas to patrol and a big budget to spend. Continental European air forces did not have to defend huge areas, most others did not have the budget. Two countries however had both, and both chose the Hurricane over the F-4: Recherche and Australia. The Rechercheans had a satisfactory third-generation multirole fighter in shape of the Hale Typhoon, which emphasized simplicity and versatility and sold reasonably well internationally (apart from Recherche itself, it was introduced by Patagonia, Kenya, Qatar, Lebanon, Malaysia, Singapore and New Zealand), but was no dedicated air-superiority fighter. To take that mantle, the Rechercheans agreed to license-produce 100 Hurricanes in 1965 to equip two interceptor wings. Recherchean production started in 1967 and was complete in 1969. Like the RAF and the Canadians, the Recherchenas mounted no guns on their Hurricanes, and they were armed with Sparrow and Sidewinder missiles. Due to the small size of the extant Recherchean aircraft carriers, no naval version was acquired; by the time the Rechercheans replaced their carriers with ships large enough to operate the Hurricane, the production run was long over.

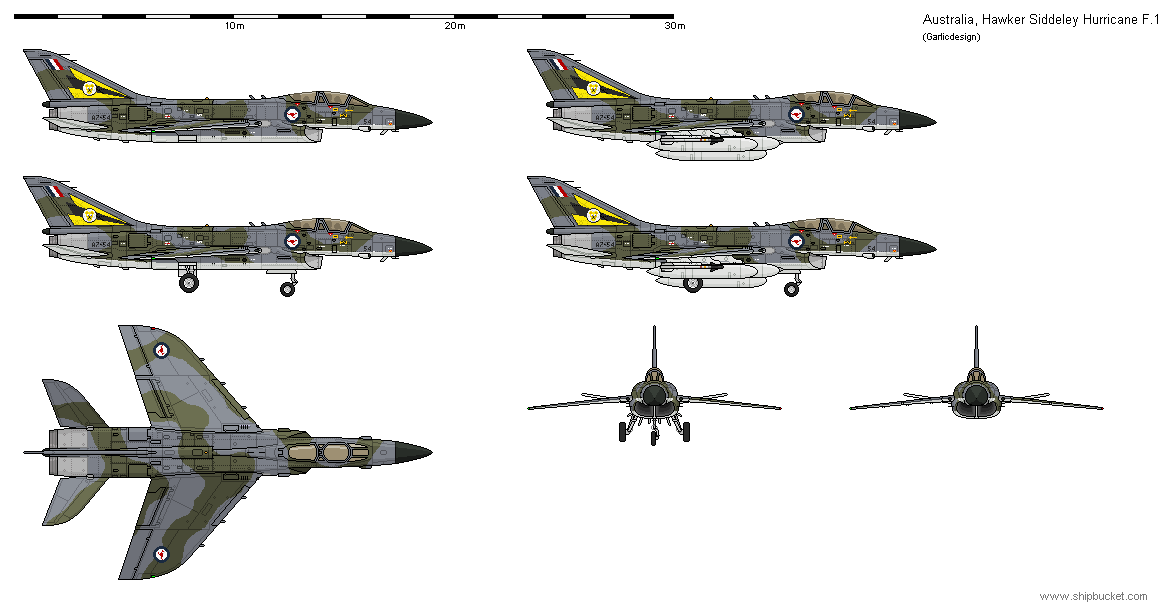

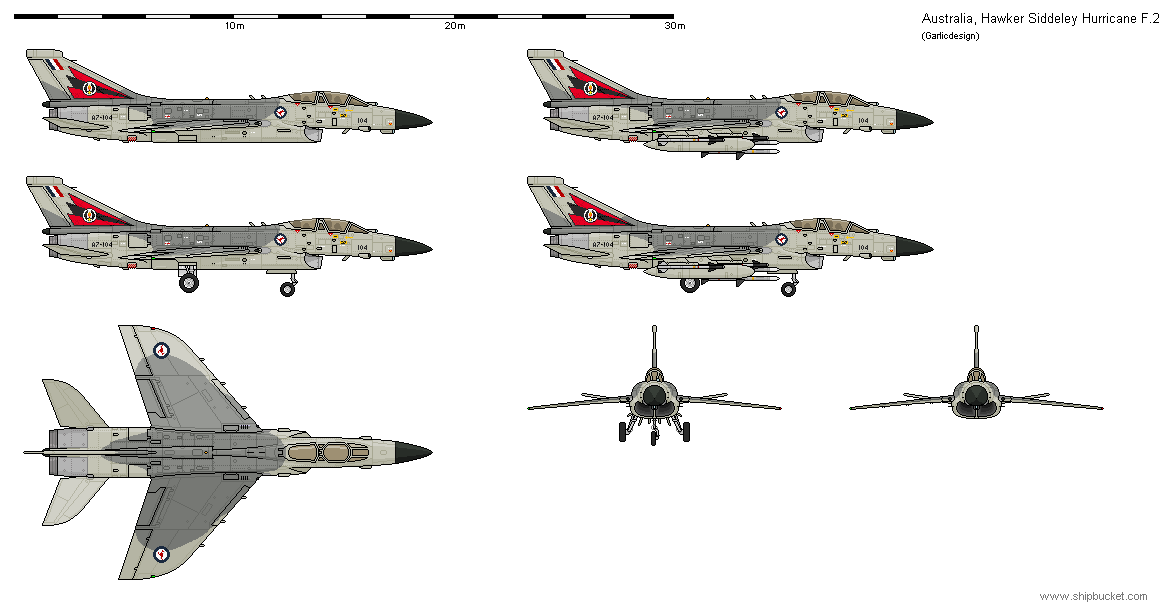

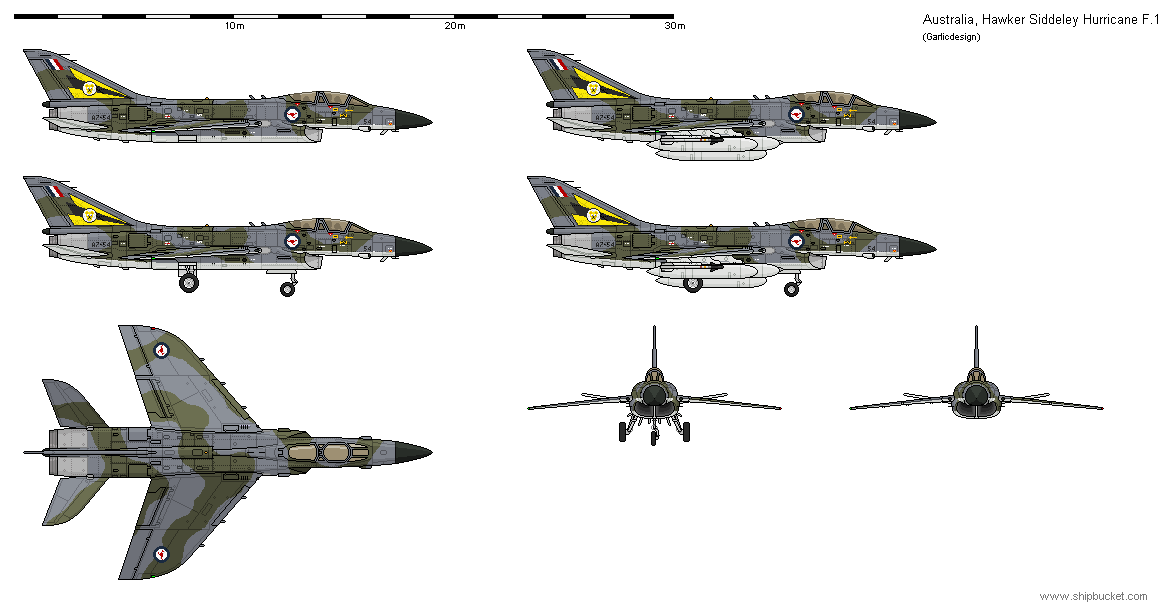

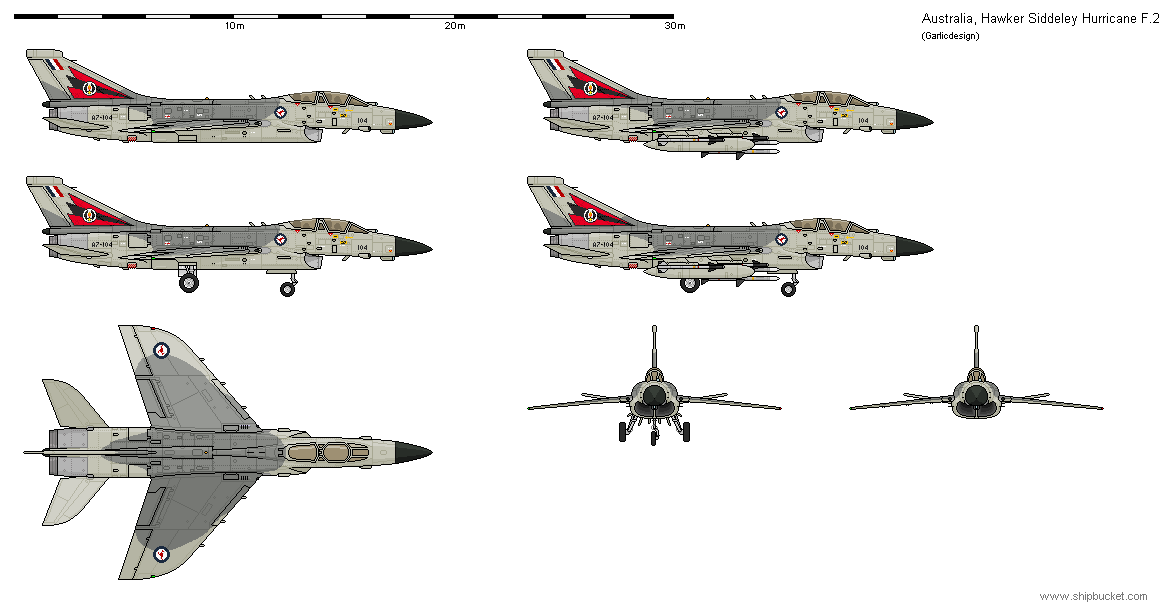

Australia decided to buy 60 Recherchean-built Hurricanes for two interceptor squadrons in 1967, relegating the Mirage III to the tactical fighter role. They were delivered as kits by Hale and assembled by GAF between 1969 and 1970s. They differed from the Recherchean version by having the 30mm cannon installed from the start; otherwise they had the same armament.

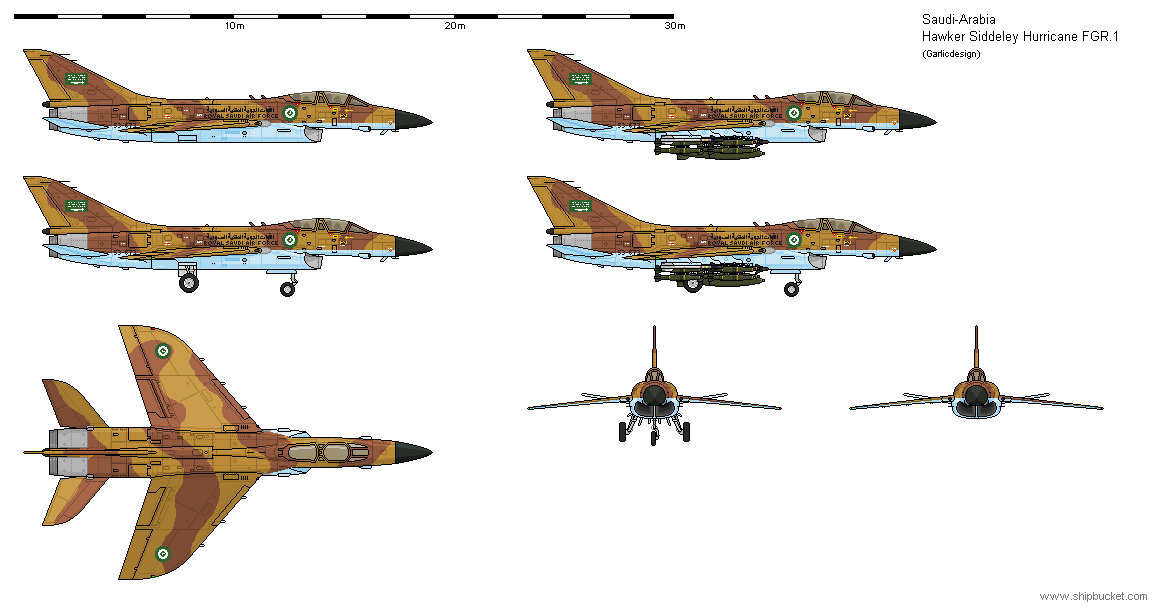

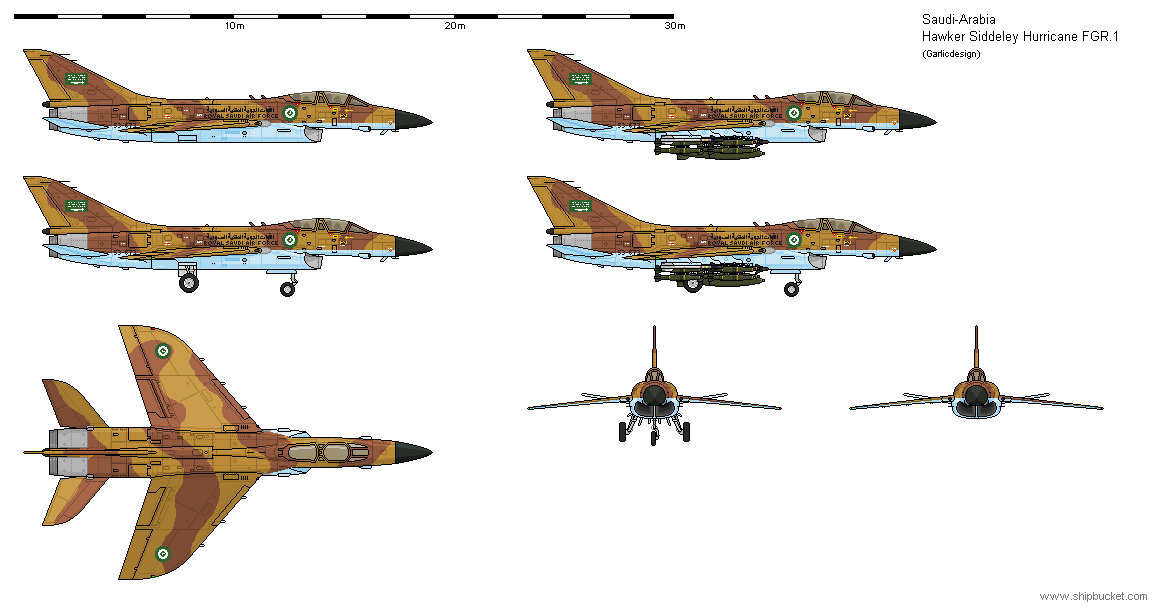

Hawker Siddeley meanwhile continued to market the Hurricane, but usually came out second best against the F-4 or – in Germany’s case – the Mirage F.8. India was interested, but the 1971 war against Pakistan prevented an acquisition. A South African deal was nearly struck in 1969, but then embargoed by HM government. Fortunately, the Royal Saudi Air Force stepped in and bought 50 machines on FGR.1 standard in 1970, which were delivered in 1971. Unlike all other Hurricane users, the Saudis employed the type as a low-level attack bomber, relying on the Lightning for air defence. In that role, the Hurricane proved equally useful; maximum loadout was a 908kg bomb and up to twelve 454kg bombs or twenty-four 227kg bombs, totaling 6.356 kilograms of payload.

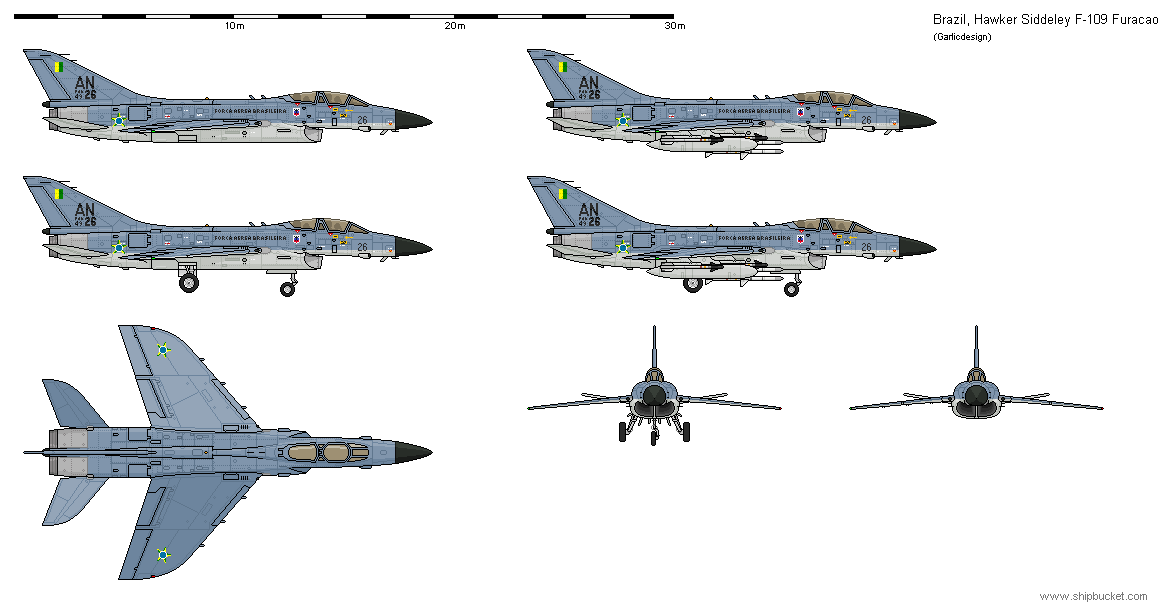

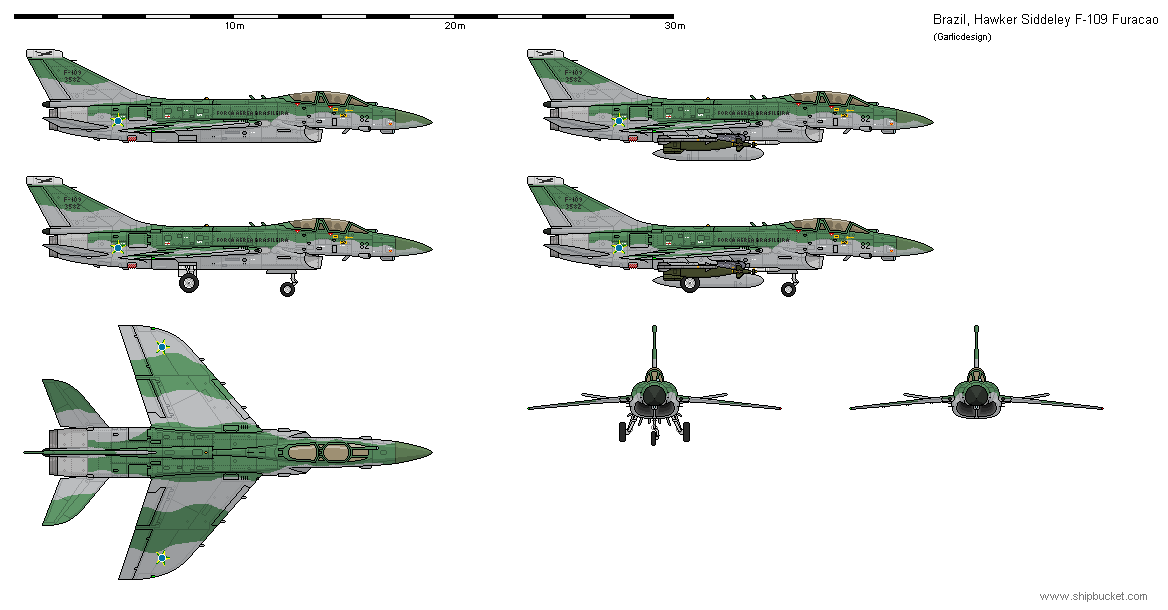

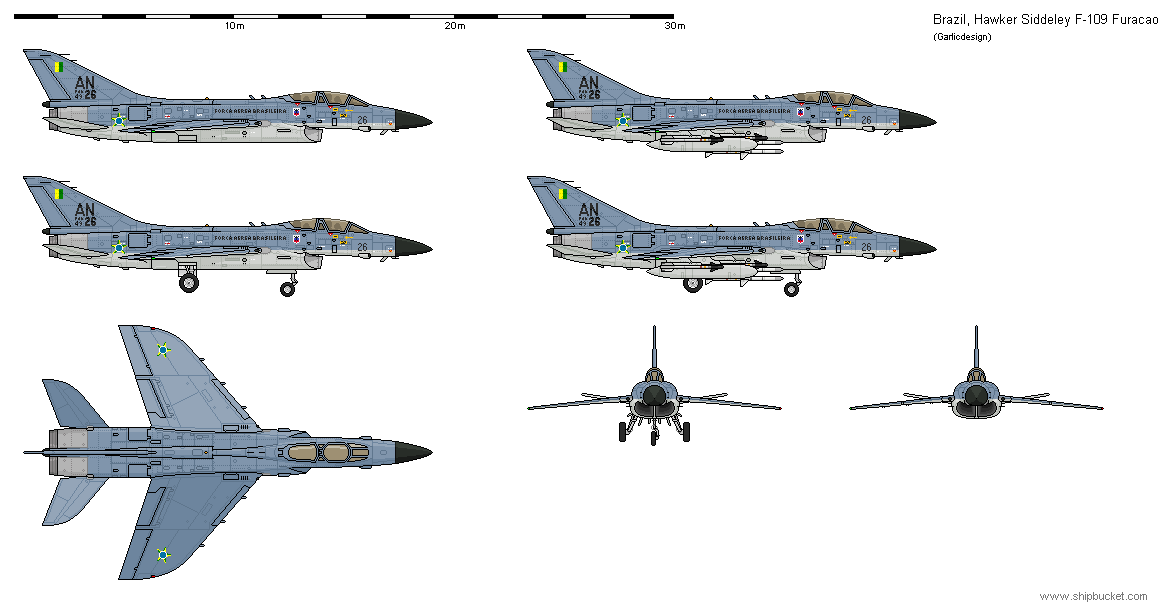

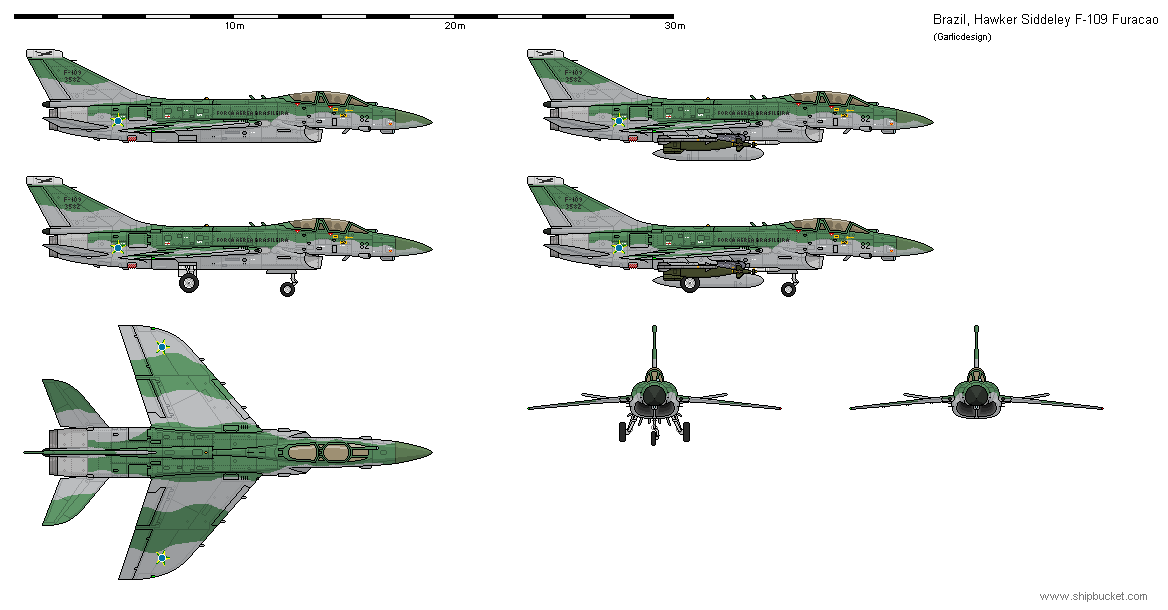

The final export customer was the Brazilian Air Force, which ordered 80 machines in 1970 for delivery in 1972/73. These were subsidized by the British government in order to strengthen Brazil’s position vis-à-vis Thiaria, and the Brazilian machines were actually the most advanced combat aircraft in South America till Thiaria introduced the Siolpaire. They were on FGR.1 standard with cannon and employed both as fighters and strike aircraft. Hawker Siddeley delivered 40 complete airframes, which were rewired for US armament by EMBRAER, and 40 kits to be assembled in Brazil. They were dubbed Furacao in Brazilian service. The last of these machines was commissioned late in 1973.

When production was complete, 430 units had been built in the UK, 160 in Recherche and 80 in Canada, for a total of 670. It was the last British-led joint commonwealth jet fighter programme; her successor (the Tempest) was already developed under project leadership of the Recherchean Hale company. In British service, the Hurricane played a key role in the first Lemuria crisis in 1977, pretty much by itself won the Patagonian war in 1982, nearly came to blows with the Soviets during the Red October incident in 1985 and was the most numerous non-American airplane employed in the Second Gulf war 1991. By that time, the RAF F.1s had been modernized to F.2 standard with a modern ECM suite, chaff/flare launchers, aerial refueling capability, FLIR, IRST, digital avionics and an upgraded radar system. Two 30mm cannon were added to the wing roots, and the Red Top missiles were replaced by Skyflash and Sidewinder. By the time of the Gulf war, the RAF Hurricanes had reached the limit of their designed service life, and they were phased out between 1992 and 1994, to be replaced by the BAe/Hale Tempest. Due to the volatile political situation after the military coup in the Soviet Union, which culminated in the 1995/6 civil war, over 100 Hurricanes were kept available till 1998 for potential use in a major crisis. Their scrapping did not commence before 1999; by 2005, only a dozen museum pieces were left.

The simultaneous upgrade from FGR.1 to FGR.4 was less comprehensive, because the FGR.1 had some of the improvements already installed. They were used for SEAD and precision strike missions during the Gulf war. They were due for replacement with Tempests in 1995, but remained in service till 1998 alongside their own successors. Only then did the greater political situation allow for their retirement and scrapping.

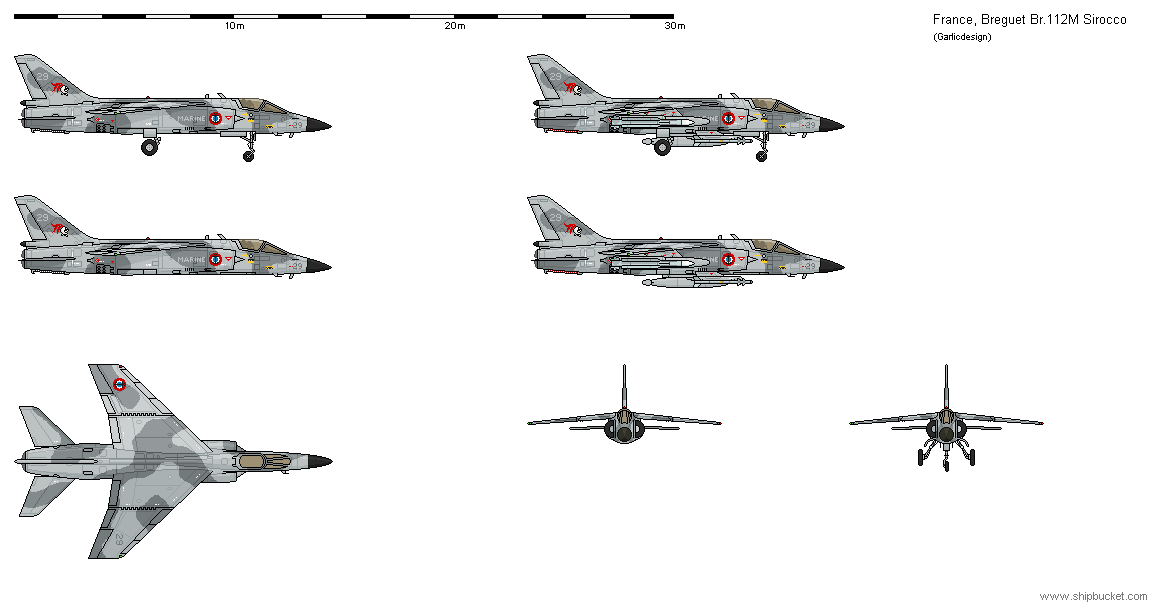

The RN’s Sea Hurricane FAW.1 had seen the hardest use, and losses and attrition had reduced the number of airworthy machines to 60 in 1990. They had been refit to FAW.2 in the late 1970s, which included all improvements built into the F.2, plus adoption of the new very long range Skydart missile; they were also adapted to fire the Sea Eagle ASM for a secondary anti-ship role. Although they were on paper the most potent Hurricane version and had acquitted themselves finely in both Lemurian incidents (added kill quote 89 - 15) and in the Patagonian war (kill quote 51 - 7), they were the first to go. HMS Queen Elizabeth had her entire Hurricane/Buccaneer air group refitted with Sea Tempests in 1989, but was still in its initial training cycle when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990. This gave the Sea Hurricane a final shot at glory; Prince of Wales and Duke of Edinburgh deployed to the Gulf, each with an Air Group of 15 Hurricanes, 15 Sea Jaguars and 15 Buccaneers (plus seven AEW/ASW/tanker aircraft and eight helicopters). Due to the ponderous size of the US supercarriers, which could not properly maneuver in the restricted waters off the Shatt-el-Arab, it was the ‘little’ allies who provided the bulk of allied carrier aviation in the Gulf. The naval flank of Desert Storm consisted of one US carrier (the ‘small’ USS Midway), accompanied by Britain’s HMS Prince of Wales and Duke of Edinburgh, France’s Verdun, Recherche’s Recherche and Thiaria’s Oirion. After the Gulf war, the Sea Hurricane was quickly phased out and replaced with the Sea Tempest till 1995.

Canada’s Hurricanes had a less eventful life than Britain’s. They remained in service for over thirty years, courtesy of their structural robustness. They were modernized in a similar way than the British F.2, but never received the 30mm cannon. When 55 still airworthy Hurricanes were retired without replacement in 1998 after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, they were among the last purely missile-armed interceptors. They still mounted the obsolete AIM-47 missiles, a decade after the USA had retired them along with the last F-106s.

The Recherchean Hurricanes were active during both Lemuria crises in 1977 and 1987, and the Second Gulf War 1991. Refit to F.2 was executed in the early 1980s, in a similar way as Canada’s Hurricanes (meaning without the cannons). They also received the Skydart missile of the Sea Hurricane; though a basic capability was there, they were never employed in the strike role. They were the last Recherchean aircraft type to be replaced with Tempests; like their British pendants, the Gulf war lengthened their service period. They were kept at extended availability till 1997, then scrapped and replaced with Tempests.

The Australian Hurricanes were modernized in 1980/2 along the lines of the RAF F.2s. Like their Canadian pendants, they remained in service when the rest of Australia’s inventory was replaced with F18Ls in the mid-1980s and were often seen over Indonesian waters whenever things in East Timor boiled high. They were not equipped with the kind of long range missile their Canadian, Recherchean and RN pendants had received, relying on Sparrows and Sidewinders throughout their careers. They were strike capable, but not used in that capacity. They were replaced with Super Hornets around the turn of the century.

The Saudi Hurricanes were very active in the Gulf war, however hampered by the poor training level of their pilots. They had received their FGR.4 upgrade in 1986/7 and still usually flew laden to capacity; the machine shown below carried 24 retarded 227kg bombs for low level strike, plus four Sidewinders, Lantirn and additional ECM. The Saudis hardly ever mounted auxiliary tanks. Their Hurricanes were replaced by F-15S Strike Eagles in the mid- to late 1990s. The last Saudi Hurricane was retired in 2001.

Brazilian Hurricanes went to war against Thiaria in 1985 and 1997. Although they had not been modernized, they fared well in 1985, unless they met Thiarian Mirage F.8s; against the other Thiarian long-range fighters (F-101D and Su-15), they proved superior, and achieved an overall kill ratio of 7:2 (unfortunately, these 7 kills were virtually Brazil’s entire tally, against a total Thiarian score of 44, 19 of which – including both Hurricanes – claimed by Mirage F.8s). In 1997, despite having been modernized to F.2 standard in the late 1980s, the Hurricane had to fight Siolpaires and Mirage 4000s, with predictably disastrous results. No less than 20 were lost to little gain (3 kills). After the 1997 conflict, the Furacao was progressively relegated to ground-strike missions. When the EMB.340 Arqueiro multirole fighter eventually became available after the turn of the century, the days of the Hurricane drew to a close, but due to persistent teething troubles of the Arqueiro, the last Furacao was not retired prior to 2008, after 34 years of service.

Greetings

GD