Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Moderator: Community Manager

-

emperor_andreas

- Posts: 3908

- Joined: November 17th, 2010, 8:03 am

- Location: Corinth, MS USA

- Contact:

Re: Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Very impressive work!

Re: Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Do "stolen double-ended Matsushima" is up-to-come?..............

"You can rape history, if you give her a child"

Alexandre Dumas

JE SUIS CHARLIE

Alexandre Dumas

JE SUIS CHARLIE

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

Hello again!

Mexican Empire:

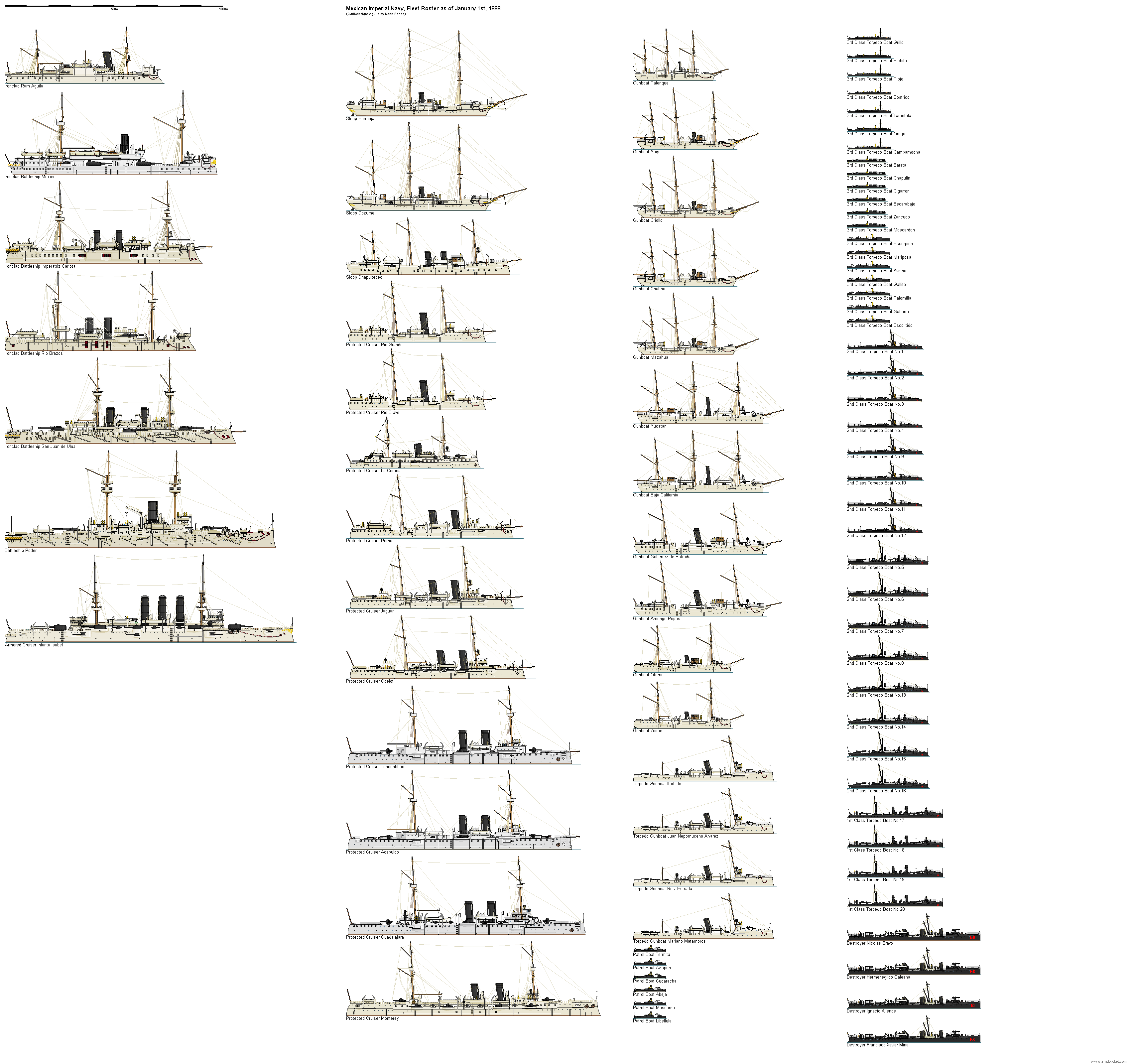

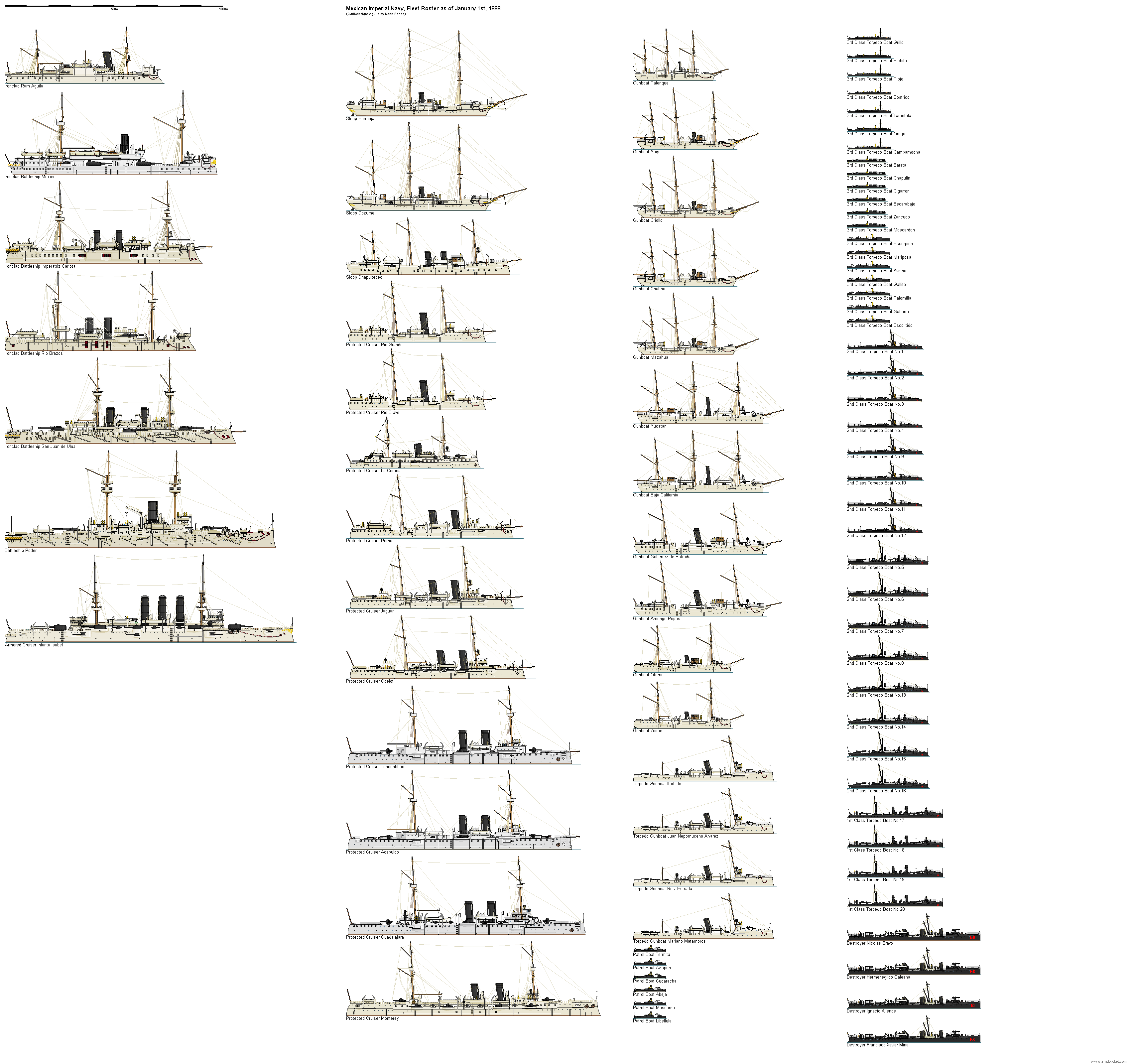

B. Part II – 1891 to the Emperor’s death (1907)

8. Halcyon days

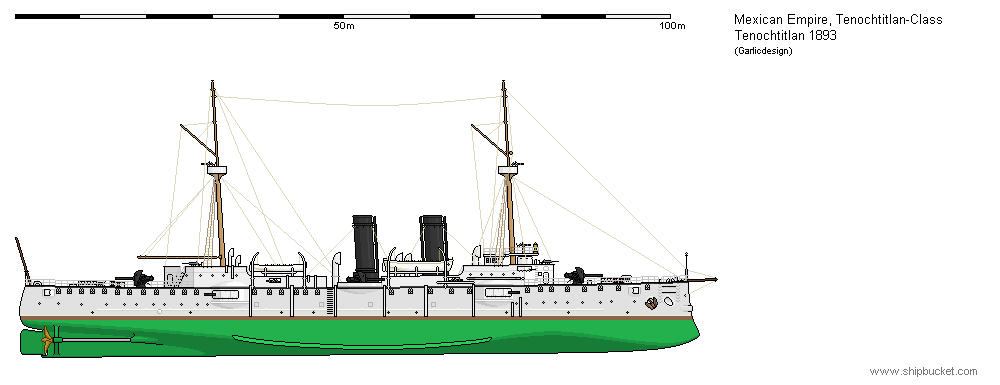

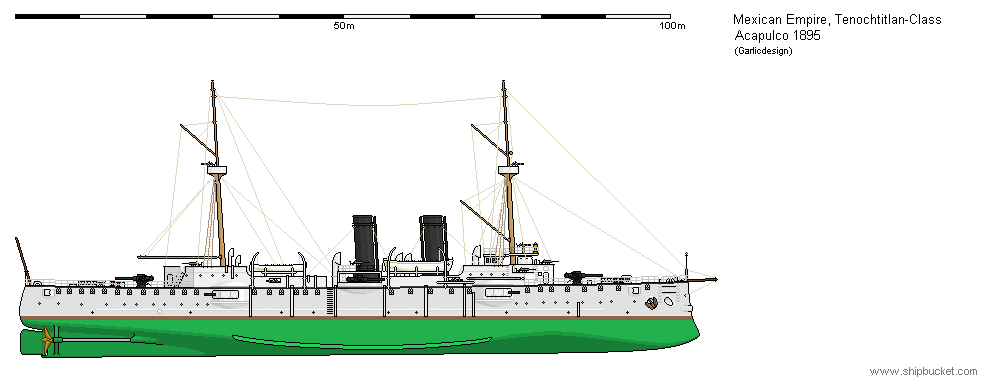

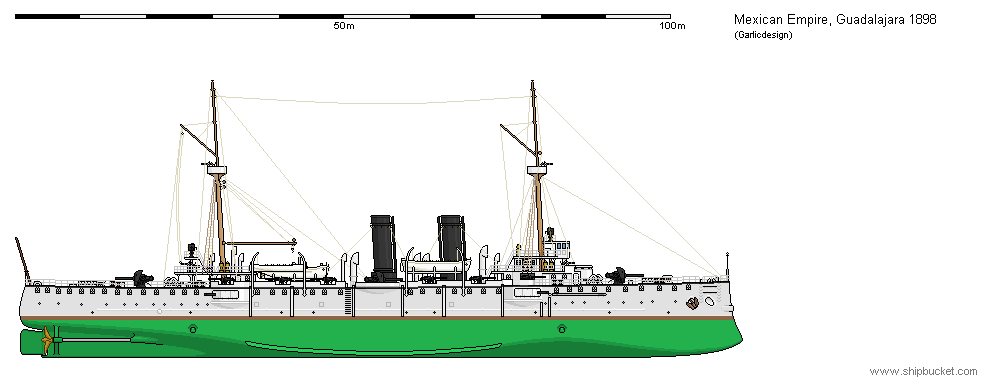

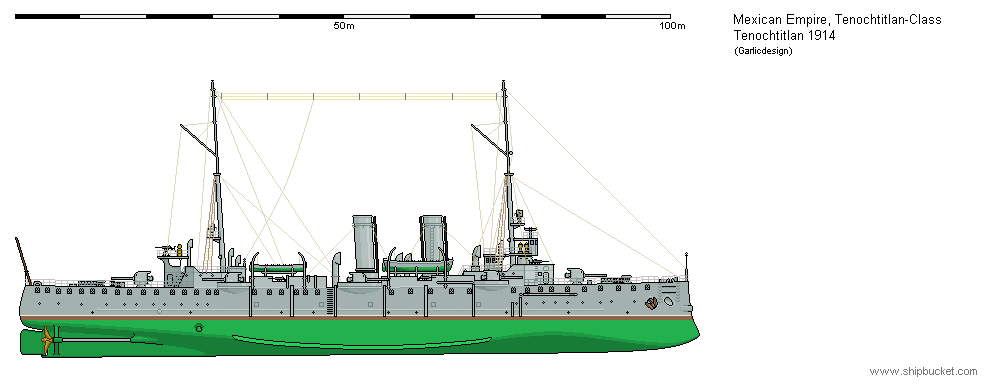

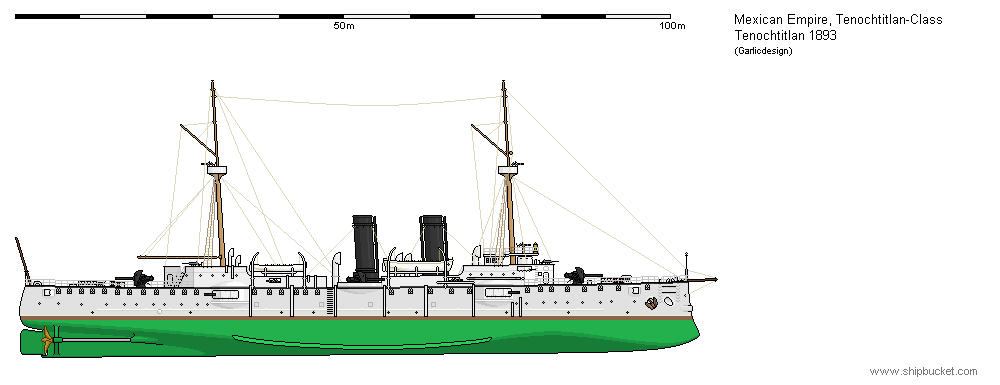

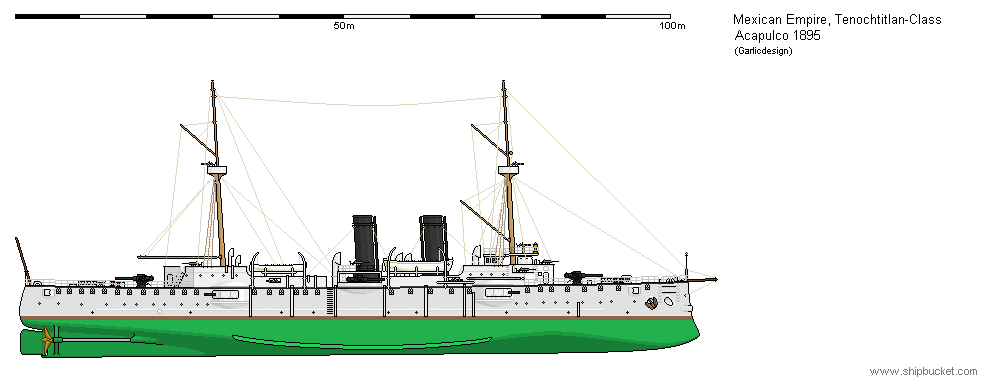

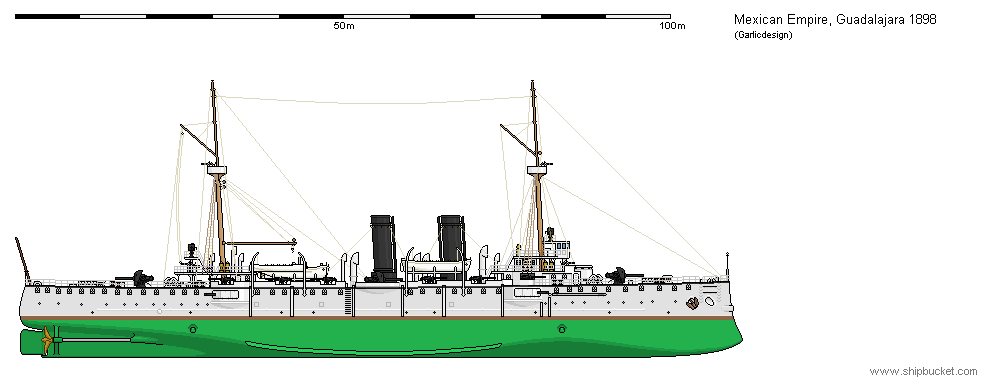

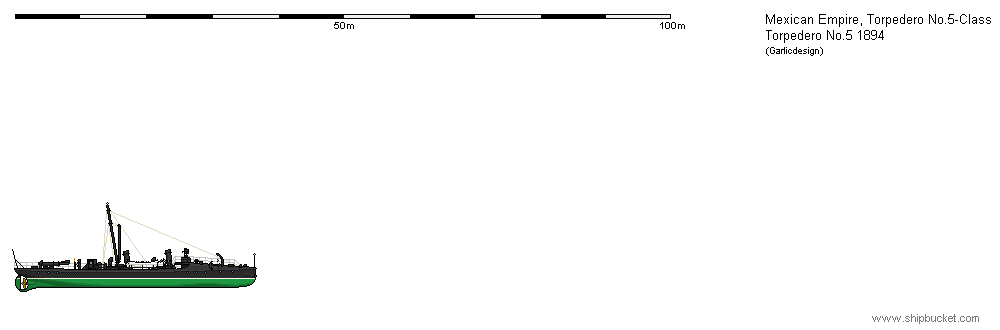

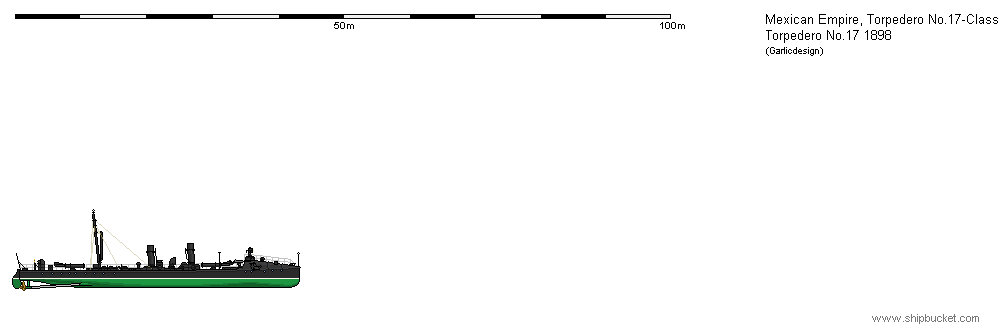

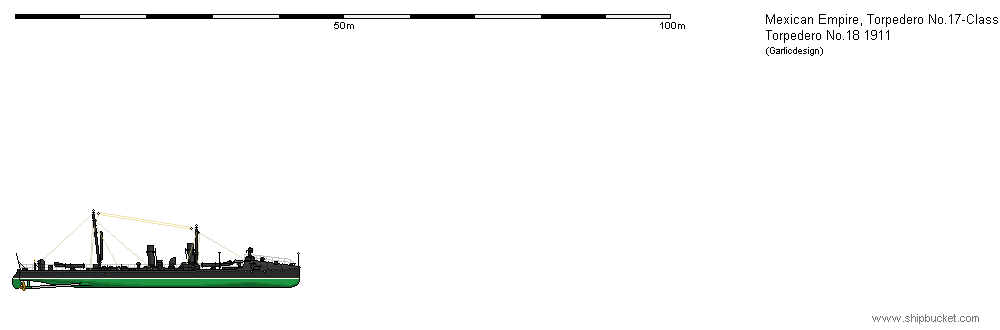

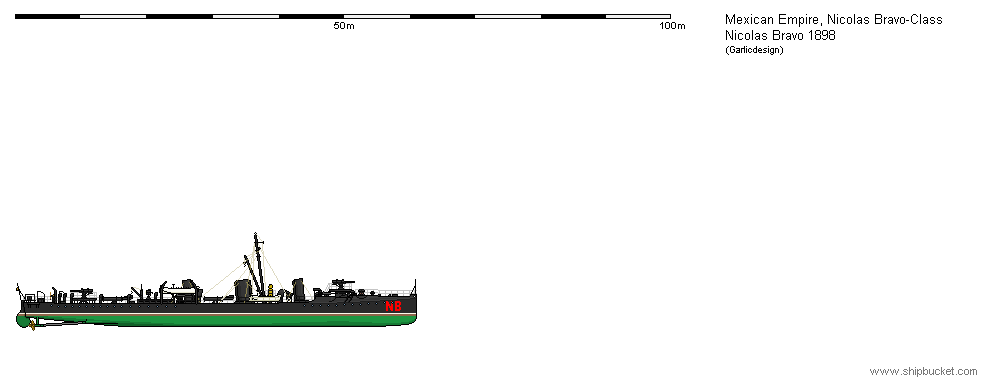

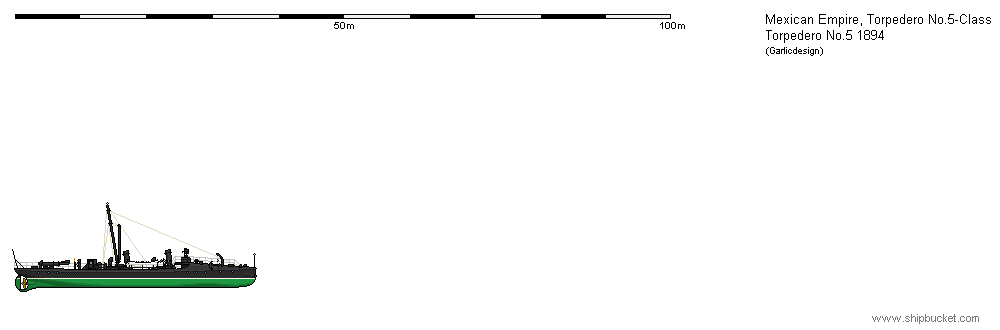

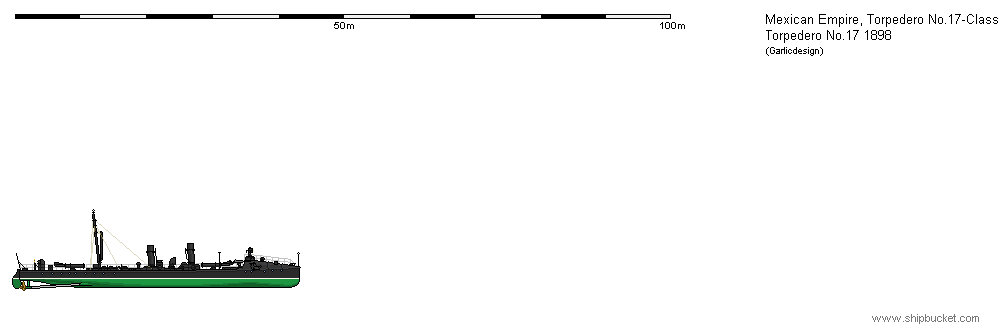

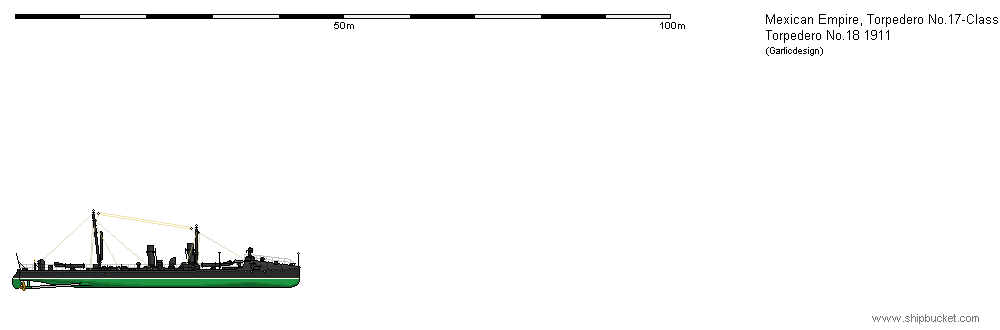

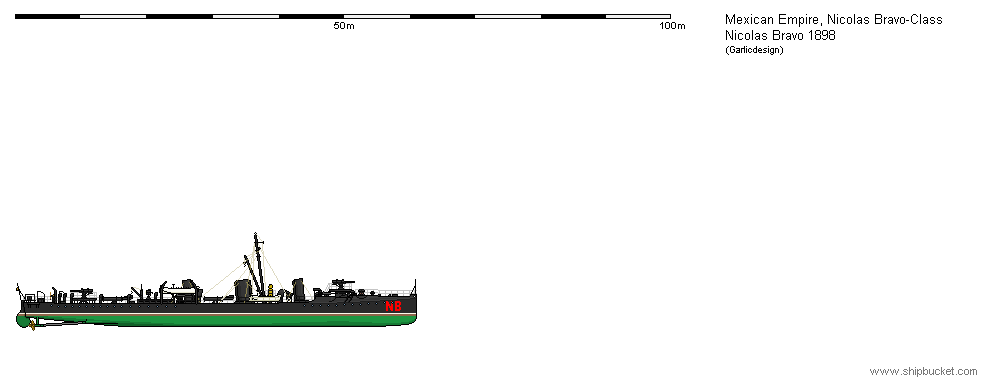

Although the clash with the USA had ended in President Harrison successfully bluffing Maximilian into abandoning his aspirations on the channel project, the Mexican Empire reached the peak of its internal popularity. Maximilian's image was not damaged by the defeat; the Mexican public had never wanted a war and was grateful when the Emperor chose peace over honor. Mexico's economy continued to prosper, fueled not only by private US and more or less private European investments, but also by increasing domestic activities, and the final decade of the 19th century was widely regarded as the country's golden era. Great improvements in health care drastically curtailed infant mortality and increased lifespan; between 1880 and 1915, the nation nearly doubled its population from 10.000.000 to 18.700.000. More Mexicans than ever received a share of the nation's wealth, and native Americans participated in a way that would have been unthinkable across the Rio Grande; during the 1890s, there even was substantial immigration to Mexico from Spain, Italy and the Habsburg Empire. Between 1880 and 1900, Mexico's GDP nearly quintupled from 6.200.000 to 29.400.000 dollars; that year, the per capita figure equaled Spain’s. Steadily increasing revenues enabled the emperor to keep nurturing his fleet; during Tegetthoff’s tenure as Minister of the Navy, the naval budget had quintupled, and in the 1890s, it doubled again. Even the teenage Infanta Isabel warmed to naval matters, in the shape of a handsome Lieutenant named Juan Alejandro Beltran, ten years her senior, who soon became her closest confidant and used imperial patronage to have himself promoted to Captain at age 27, Rear Admiral at age 31, Vice Admiral at age 35 and Full Admiral and Minister of the Navy at age 39. Only two generations before, Beltran’s grandfather had fought for the liberal rebels against the Empire (he was killed in action in 1866); now the family was staunchly monarchist, which was exemplary for most of Mexico’s bourgeoisie. Beltran was not only charming and charismatic, but also tirelessly energetic and became the dominating figure in Mexican naval affairs for nearly twenty years, although he never held a command at sea; the gallant but lazy Cordona quickly came to rely on him completely. In a completely different way, so did the Infanta. In 1896, she was married to a strapping German Prince named Karl August of Hohenzollern, the youngest son of Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, whose claim on the Spanish Throne had led to the Franco-Prussian war of 1871. Handsome and looking dashing in a uniform (which pretty much sums up his redeeming features), he became known in Mexico as Principe Carlos Augusto. On his departure, Kaiser Wilhelm II is reported to have said ‘He’s barking mad most of the time, and a scheming asshole in his lucid intervals. I hope they never give them any actual power,” which sums up everything else about him. Infanta Isabel detested her pompous and abusive husband from day one. Beltran on the other hand felt rather more enthusiasm for 'his' navy than for the Empress and played his relationship with the princess for all it was worth. He secured funds to improve training, doctrine, payment and living conditions for naval personnel, which quickly made him the most popular officer in Mexico’s armed forces. While he headed the materiel office in the Naval Ministry between 1893 and 1897, he turned to Great Britain as main supplier of Mexican ships, because Austria’s shipbuilding industry was not yet able to deliver what he wanted. Of the large 1892 fleet modernization program, two big pre-dreadnoughts, two armored cruisers and Mexico's first six real destroyers were British-built. A third battleship was acquired from funds of the program in 1895 from a British yard after the Chinese who had ordered it were no longer able to pay after their defeat against Japan in 1894. Austria was however not entirely sidelined; a coast-defense battleship was ordered in 1893, and the year after, the Tampico naval yard laid down a copy, which would become Mexico’s first domestically built capital ship. Of the four first class protected cruisers laid down between 1892 and 1898, three were Mexican-built, and only one was built by STT. The program also provided four gunboats and twelve torpedo boats. For the first time in Mexican naval history, warships were built in homogenous classes, and Mexican engineers and designers were sent to Great Britain to improve the capabilities of Mexico’s naval yards. While the navy prospered under Beltran, the 1890s also saw the rise of a much more malign figure, General Victoriano Huerta, who assumed the post of Chief of Staff of the Mexican Army in 1895 at age 45, and became its Commander-in-Chief in 1907. Like Beltran, he served under ineffectual superiors (first the honorable, but slightly senile Felipe Berriozabal until 1900, then the cultivated, but complacent Bernardo Reyes until 1910) and had de facto free reign long before he became Minister of war himself in 1910. Unlike Beltran, who was capable and ambitious, but not corrupt, Huerta – who was no bad soldier too, being an able organizer with a good grasp of technological developments, and a talent for asymmetric warfare – developed corruption from an art to a science. His efforts to increase the army budget always served his own interests, as he shamelessly enriched himself. Under his leadership, the Mexican Army was increased in numbers (by 1900, there was a standing force of 100.000), equipment and training, but it gradually lost its nature as an army of the people, becoming an instrument of suppression. It was almost ironic that the first conflict it fought under Huerta's tenure as Chief of Staff was a war of liberation.

9. More Spanish troubles

Popular resentment towards the increasingly inept, corrupt and brutal Spanish rule in Cuba had mounted during the 1890s till open conflict was inevitable. This resentment was shared by many in the USA, and the voices arguing for intervention became ever louder; on the other hand, the Spanish government’s notion of national honor categorically prohibited relinquishing control of their Caribbean colonies. The situation on the Philippines was quite similar, with open revolt against Spanish rule in progress, and the additional complication of Japan and Koko competing with the USA to aid the rebels. In Mexico, sympathies were divided. The Spanish were still profoundly disliked, and public opinion was all in favor of assisting secession of their remaining colonies in the Gulf and the Caribbean. On the other hand, the Imperial government understood that a war between the USA and Spain was a foregone conclusion; the inevitable US victory would not result in liberty for Spain’s colonies, but in a more efficient and powerful new ruler for them, which Maximilian’s advisors considered the worst case scenario. Retaining the status quo was considered preferable, and the Imperial government tried to moderate the boiling conflict between the US and Spain. Unfortunately, nobody listened, and the Americans sent their newest and most powerful battleship, USS Iowa, to Cuba in order to show their sympathies to the rebels. After Iowa had blown up in Santiago harbor on February 15th, 1898, due to decaying gun propellant, the Americans escalated tensions till Spain declared war on April 23rd, 1898. As early as May 1st, Spain’s naval presence on the Philippines was wiped out by the USN; the US fleet (battleship Oregon, armored cruiser Brooklyn and four smaller cruisers) hopelessly outgunned the local collection of Spanish unprotected cruisers and gunboats under Admiral Montojo. Spain focused all efforts on Cuba and sent every available warship across the Atlantic under Admiral Cervera. He could not prevent destruction of Spain’s scant naval presence at Cuba in a one-sided engagement off Guantanamo Bay on June 6th, but engaged the USN in a major battle on July 3rd off Santiago. The Spanish fleet, which had been at the nadir of its fortunes when Tegetthoff defeated it in 1885, had seen significant reconstruction and strengthening; corruption and inefficiency had been rooted out, fighting efficiency was much improved, and new equipment had been acquired. The battle of Santiago therefore was an unexpectedly even contest. The Americans fielded six battleships, an armored cruiser and five protected cruisers; the Spaniards brought five battleships, six large cruisers (four armored) and three smaller cruisers. Only the Spaniards had modern destroyers and torpedo gunboats; the US on the other hand had a dozen small torpedo boats. It was the largest engagement in the Americas since the War of Independence. Spanish total losses were higher than US ones, but only the Spaniards had 240mm rapid-reload guns on three of their ships, while the main guns of all US battleships were slow-firing. Peppered with multiple hits, all US battleships needed repairs, while those Spanish ships that had not been sunk were virtually undamaged. Having fought the USN to a stalemate at sea – for the time being; the Americans started to repair their ships within days of the battle – the Spaniards kept losing on land. They had not been able to prevent the insertion of an US volunteer force aiding the Cuban rebels, and the Rough Riders triggered uprisings wherever they went. Soon, the USA would be masters of Cuba, even without a decisive naval victory. In this situation, the Mexicans intervened and started to actively support Cuban rebels themselves, declaring war on Spain on July 18th. Only four days later, their fleet met the weakened Spaniards off Mayaguana. The Mexicans fielded four battleships, an armored cruiser, six smaller cruisers, two torpedo gunboats, six destroyers and twelve torpedo boats. Although the Mexicans lost an old ironclad to a magazine explosion, they sank a new Spanish battleship and a protected cruiser. The Spaniards – having been unable to resupply after their clash with the USN – were critically low on ammunition and had to break off the engagement. While they retreated to Santiago, the Mexicans coaled and re-supplied at sea – something nobody had believed they were capable of. A few days later, Prince Carlos Augusto himself landed at Guantanamo with a force of 4.000 well-armed volunteers. The Spanish base – heavily fortified at great expense during the last ten years and only recently opened – was taken without much resistance, the garrison fighting rebels deep in the island’s interior. President McKinley made the Mexicans aware in rather undiplomatic terms that the USA would not tolerate any Mexican land grab on Cuba, to which Mexico's foreign minister Miramon replied that Mexico had no intention to do that; all they were interested in was the end of Spanish colonial rule and freedom for everyone. Unfortunately, this was exactly what McKinley himself had been saying all along, so he could hardly admit he had never meant it seriously. Both sides thus kept fighting the Spaniards, secretly preparing to fight each other. On August 4th, US backed rebels unilaterally declared Cuban independence; Carlos’ Augusto’s proxies followed suit five days later. Town and port of Santiago went to open revolt. Without a base, the Spanish fleet needed to break out, with unrepaired damage to most of their ships and hardly any ammunition in the magazines. Just outside Santiago, the Mexicans were waiting, and the second battle of Santiago on August 15th went down a lot more lopsided than the first. Few Spanish ships made it to Puerto Rico; the Mexicans lost a protected cruiser and a torpedo gunboat. On land, things went less smoothly. So brutal was Carlos Augusto’s treatment of prisoners that the Spanish would fight him to the last cartridge; when the Rough Riders and their allies showed up, they’d just surrender. Ironically, many Cubans relished Carlos Augusto’s blundering more than Roosevelt’s sweeping success. In their lust for revenge, letting the Spaniards surrender and sending them home seemed less appropriate than torturing them to death. On August 20th, the last major Spanish garrison in Habana, out of provisions and stricken by yellow fever, surrendered to American-backed rebels. By that time, the US Pacific fleet was back from the Philippines, and some damage to the Atlantic fleet had been patched. When both fleets faced off near Cuba’s westernmost cape on August 27th, it was the Mexicans who were outnumbered and low on ammunition. The choice now was war against the USA or diplomacy. Maximilian and Miramon knew they stood no chance in a prolonged war and entered negotiations. Cuba became independent from Spain, the USA and Mexico promised each other to respect Cuba’s neutrality, and Spain had to cede Puerto Rico and the Philippines to the USA. The fortress of Guantanamo was closed and its heavy guns disabled (the Mexicans however secretly purloined their breechblocks for possible later use). Carlos Augusto was greeted a hero in Mexico, fueling his already huge self-image beyond the threshold of megalomania. The Americans meanwhile occupied Puerto Rico; the remnants of the Spanish fleet had already left. They also annexed Hawaii, which alarmed the Japanese, who had been working towards establishing a protectorate of their own over the archiple with its large population of Japanese immigrants. Japan and Koko reprocitated by arming and encouraging Filipino nationalists to take up arms and fight for full independence. A heavy-handed and rather clumsy American crackdown resulted in a full blown war, which raged from 1899 through 1902, claiming almost 200.000 Filipino lives. When Japanese arms deliveries to the rebels were uncovered, the USN blockaded the Philippines, resulting in several face-offs with Japanese warships. All-out war could be avoided by British diplomatic intervention, but the episode sparked considerable anti-American bitterness in Japan and Koko, which would result in severe repercussions two decades later.

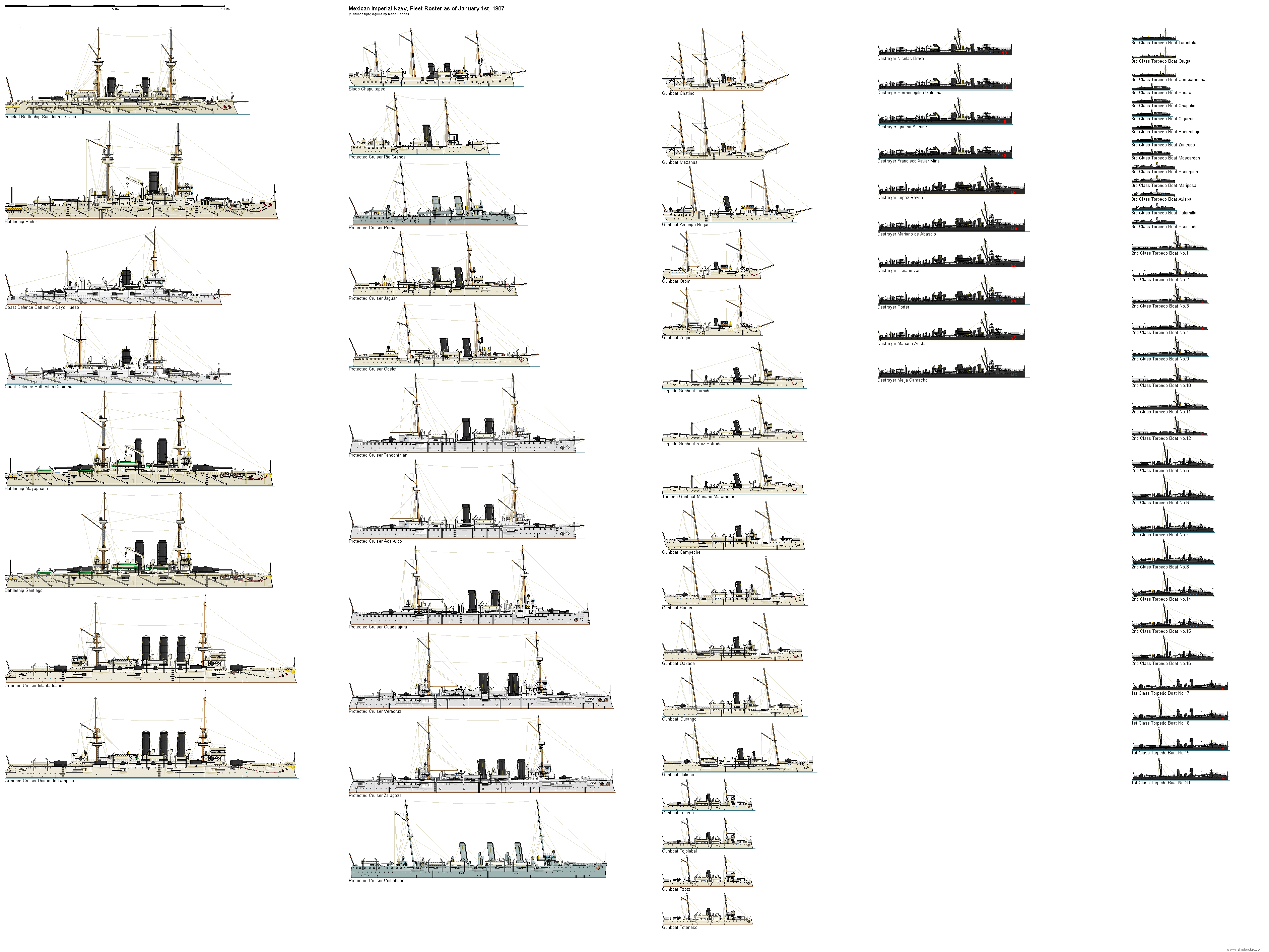

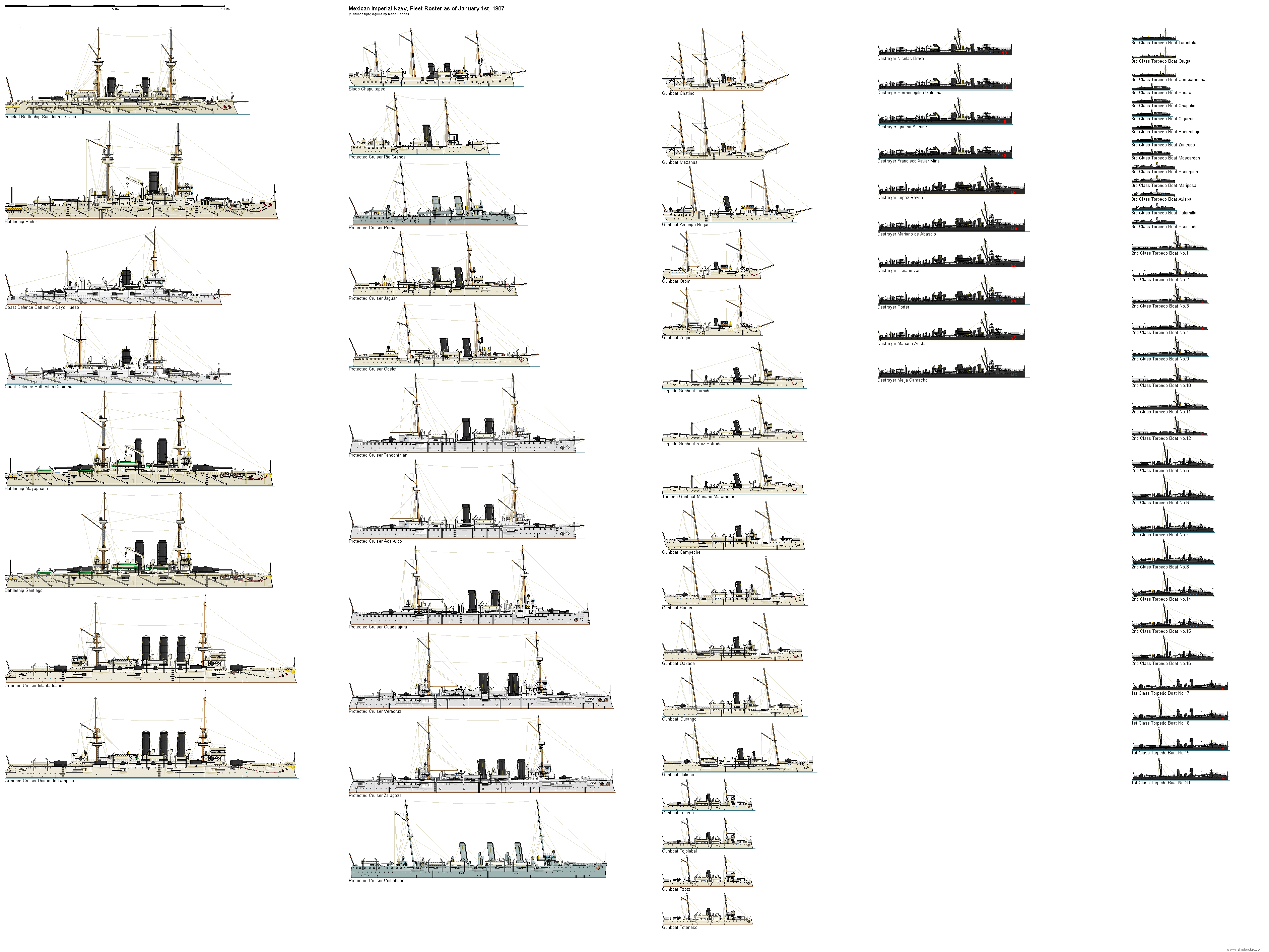

10. Emperor sees 20th century, doesn’t like it, dies

When Carlos Augusto returned to Mexico, he celebrated the first Mexican victory on land against an external enemy since the 1820s. General Huerta however knew that Carlos Augusto had not paid the price for his force’s deficiency in equipment and training only due to the weakness of the opposition. In the following years, Huerta managed to scrape off a larger part of the defense budget for itself and buy modern heavy equipment (and a large estate for himself, of course). Discipline of the army was rigorously enforced, but training and doctrine remained old-fashioned, logistics were neglected, and payment of ratings, noncoms and junior officers was only a third of what could be earned in the navy. Although the navy had dominated the Spaniards, its funding decreased in the years after the war. As General Huerta put it, the navy had performed flawlessly after all, and did not need further improvement. Instead, Huerta oversaw construction of two huge arms manufacturing complexes at Mexico City and Guadalajara; the former made guns of up to 150mm caliber under Skoda license, the latter made the ammunition for them. Another company founded by Huerta made the famous Mondragon rifle, the world’s first semi-automatic weapon to be adopted as service weapon by the Imperial Marines (it was also license-made in Germany during the First World War). Although these factories needed state subsidies throughout their existence, any profits generated of course largely went to Huerta’s personal pockets; navy orders in particular were grossly overcharged. With economy entering a phase of stagnation - attempts to 'Mexicanize' the economy and reduce the influence of foreign, especially American, investors had scared foreign capital off - the beginning of the 20th century marked a period of erosion of imperial authority in Mexico. German investments never were large enough to make up for the loss of US dollars, and German businessmen acted as undiplomatic as their US pendants, and then some. Worse, their arrogance was laid at Prince Carlos Augusto’s door, who was one of them, after all. Being himself, Carlos Augusto did little to improve his public image. His notion of marital fidelity was no more sincere than that of the Empress, if rather less discreet and considerably more profligate. He displayed contempt of Congress and everything that passed for democratic institutions in the Empire, and his attitude towards indigenous Americans, Afro-Americans and Jews would have earned him a place at the Wannsee conference. With Carlos Augusto's backing, General Huerta, who saw communist insurgence everywhere, tirelessly worked to transform Mexico into a police state. To regain some popularity, the Emperor signed a constitutional reform giving Congress more power in 1901; in many respects, Mexico's constitution of 1902 was more democratic than Germany's or Austria's. Rather than smoothing over the discontent, this new freedom only made the opposition bolder, resulting in increasing reluctance to vote money to the armed forces. Between 1897 and 1907, only a single battleship, three cruisers and four destroyers were approved, plus six gunboats, to keep the shipyards occupied. The Emperor - urged by the Infanta, for obvious reasons - had Beltran appointed Minister of the Navy in 1902 upon Cordona's retirement. In the first five years of his tenure, he had to work with reduced budgets, but still managed to bolster naval infrastructure. A torpedo manufacturing plant was opened at Veracruz in 1908, and the Tampico navy yard received a plant for manufacturing Schulz-Thornycroft boilers under license in 1911. Beltran also struck a deal with Siemens to construct a factory for turbines and electric engines in Monterey, which opened in 1913, and with MAN to build a plant for diesel engines at Queretaro, which opened 1914. A submarine construction plant was added to the Tampico naval yard and became operational in 1913. These measures enabled Mexico to build submarines and surface ships of cruiser size without imports; the only items not manufactured domestically were heavy armour plate and naval guns of more than 150mm caliber. Beltran also ensured regular payment of his crews and kept the available ships in prime condition. Large exercises were conducted and constant contact with foreign navies was maintained in order to further develop tactics and doctrine. A German naval mission from 1905 through 1909 under Captain Wilhelm Souchon, the future C-in-C of the Ottoman Navy, helped the Mexicans acquire night-fighting proficiency, perfect their maintenance routines and oversee their design requirements. Mexican warships regularly visited Britain, Brazil, Germany and Austria, and many Mexican officers were sent to train abroad. Actual combat deployments during this period were rare; the Mexicans tried to intervene several times when central American nations ran into trouble, but they invariably ran into the USN. Only rarely did they achieve their objectives. The most positive example was the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902, when several European powers blockaded Venezuela’s coast to enforce the payment of debts. Although Maximilian and especially Carlos Augusto favored the European (particularly the German) position, Mexican public opinion supported the Venezuelans in this affair, and the Imperial government was determined to settle things diplomatically before things spiraled out of control and the US ‘saved’ Venezuela the same way they had saved Puerto Rico and the Philippines. A force of two armored and three protected cruisers under Rear Admiral Greifenstein was a powerful backup in achieving a negotiated settlement. Mexican involvement enabled the Germans to give up their stubborn (and slightly stupid) all-or-nothing stance without significant loss of face, masking their withdrawal as honoring a personal plea from the brother of their closest ally. During the 1903 Panama crisis, when the Americans enforced the independence of Panama from Colombia, the Mexicans again dispatched Greifenstein with a sizeable squadron, this time including two battleships, which however faced a superior US fleet and wisely took no action that could be construed as provocative, because Roosevelt had repeatedly pointed out that he only waited for an excuse. The only positive result was a strengthening of relations with Colombia; like Venezuela, the nation could be considered an informal Mexican ally afterwards. From that point, the Americans increased their presence around the Caribbean. In order to kill further crises like the Venezuelan one in their cradles, they would intervene militarily as soon as any Central American nation experienced financial troubles or threatened to become unstable politically. Or if they struck major treaties with Mexico, which the White House reliably interpreted as a surefire sign of impending financial troubles and political instability. The result was inevitably a new government prioritizing US interests over anyone else’s. This happened in the Dominican Republic in 1904, in Nicaragua in 1905 and on Cuba in 1906. Mexican attempts to intervene were met with overwhelming force and thundering threats of total war and hellfire. In all three cases, the Mexicans had to back off, losing face every time (which was an actively pursued secondary objective of the Americans, every time). Roosevelt actually seemed to enjoy driving old Maximilian to conniptions that way; his own popularity certainly profited from his playing hardball with the Habsburgs. On the other side, the series of foreign political humiliations took their toll on Maximilian’s health, and between 1904 and 1907, the Emperor suffered three strokes. The second one permanently incapacitated him, and the third one, suffered on February 5th, 1907, killed him, aged 75. Roosevelt condoled the Mexican people with the remark that now the 20th century could begin for them.

11. Other People’s scores

In mid-1906, a Portuguese-owned limber company operating in the Amazonas rainforest close to the Venezuelan-Brazilian border accidentally discovered a major gold deposit and started to clandestinely ship mining gear down the Orinoco. When the Venezuelans found out, they nationalized the mine, and the company went bankrupt early in 1907. The Brazilian government consulted a map and found the border in that area had never been properly surveyed. That omission was made good during March 1907, to no-one’s surprise placing the mine squarely on the Brazilian side of the border. The Venezuelan government was told to vacate the area and leave behind the confiscated mining equipment, or else. Venezuela reacted by moving in troops; the resulting clash between Venezuelan regulars and Brazilian border guards in June 1907 ended with a not entirely surprising reverse to the Brazilians and a formal declaration of war. While the Brazilian army prepared to move in with overwhelming power, their navy deployed two battleships and three cruisers to blockade the Venezuelan coast. Simultaneously, the Portuguese government informed the USA that they would deploy forces of their own to Venezuela in order to reclaim Portuguese property. Since the events of 1903, President Roosevelt considered the Venezuelan government a major nuisance, and in his quest to improve relationships with Great Britain – which had somewhat suffered from his fleet building spree – he picked the side of Great Britain’s ally Brazil. Moreover, Portugal – also a British ally – was no power of any significance, so the Monroe Doctrine would not suffer too much from whatever modest forces the Portuguese could contribute. Roosevelt told the Portuguese they could attend if they placed themselves under Brazilian command, which he secretly hoped their national pride would prevent. Surprisingly, the Portuguese acquiesced and deployed a battleship, a cruiser and a destroyer to the Caribbean, placing them under overall command of the Brazilian Admiral Julio Cesar de Noronha. The Venezuelan government, not possessing any navy worth mentioning, secretly asked the Mexican government, who had saved them before, for help. With Maximilian dead and his sole daughter Infanta Isabel uninterested in Politics, Prince Carlos Augusto convinced the government to leap to the opportunity, as the Americans were obviously intending to let the Venezuelans be walloped. Admiral Moya sailed with two battleships, two armored cruisers, four protected cruisers and eight destroyers; on August 16th, 1907, he reached the Brazilian-Portuguese blockade position off La Guaira and told Noronha to sod off. Simultaneously, the Imperial government publicly declared its support for the Venezuelan cause and called for an international conference to settle the issue. President Roosevelt, who had not taken the issue too seriously, went to red alert. This was not what he had planned. The USN, which was currently preparing for the cruise of the Great White Fleet, was told to dispatch a squadron of the newest Conneticut-class battleships under Admiral Sperry, plus appropriate cruisers and destroyers, from Norfolk to La Guaira. While announcing the move, Roosevelt offered the service of the best surveyors in his pay in order to impartially determine the correct location of the border (meaning, exactly where the Brazilians had placed it). Anyone disagreeing – especially the Mexicans, for whom the whole affair was none of their business anyway – would have to face Admiral Sperry’s guns. As soon as this statement was out, Noronha gave the Mexicans six hours to retreat, or face the consequences. He was sure they would cave in. Both fleets were of approximate equal strength, and American reinforcements were under way. The old Emperor would have called it quits at this point, but he was dead, and Prince Carlos Augusto fancied himself made of sterner stuff. He told Admiral Beltran to order Moya to break the blockade, and send him another two battleships as reinforcement. Engaged separately, the Brazilian squadron could surely be defeated before the Americans were there; in the meantime, the Venezuelans could be provided with weapons and ‘volunteers’ to force the issue against the Brazilian army. When Beltran asked the Infanta for confirmation, she absent-mindedly gave it, while still incapacitated with grief over the Emperor’s death. True to Beltran’s orders, Admiral Moya let the ultimatum lapse, challenging the Brazilians to do something about it. Noronha, who was under orders not to risk unnecessary losses due to the critical situation on New Portugal, which could spark a war with Thiaria at any time, got cold feet and ordered his fleet to open the distance, but the commander of the Portuguese contingent, gung ho to uphold his nation’s honor, refused to back down and opened fire upon the Mexican vanguard. After half a bloody hour, the Mexicans had sunk all three Portuguese ships, without the Brazilians lifting a finger. Noronha retreated to the north-east and the blockade was lifted. Carlos Augusto was exultant, and at Veracruz, five transports were laden with guns and ammunition for Venezuela. The next day, the Mexican cruiser Zaragoza entered La Guaira to a frenetic welcome. Another two days later, the Americans met the Brazilians, and both fleets headed for the showdown off La Guaira. Neither the Mexican reinforcements nor any of the transports were anywhere near, and it was painfully obvious that Carlos Augusto had overplayed his hand. As the Imperial government frantically sought for a way out of the conundrum, the ambassadors of friendly nations were contacted. When both fleets already circled each other, the Kaiser, of all people, cabled an offer to send surveyors of his own, to work together with the Americans and attain a truly impartial result which would be acceptable to both sides. The Imperial government jumped at that solution and unilaterally accepted it; neither Carlos Augusto, who wanted to slug things out, nor the Venezuelans were consulted. President Roosevelt was of one mind with Carlos Augusto this time and wanted to force the issue, but the Brazilian government – fearing Thiaria might take advantage of any Brazilian entanglement – caved in and accepted the German offer as well. This development rendered the Americans in the absurd situation of being the only ones not interested in a peaceful settlement. Roosevelt badly wanted to sink the Mexican fleet, but he needed them to fire the first shot; unfortunately, they no longer had any reason to do so. At that point, childish as it was, it was only a question whose fleet retreated first. Having been on station longer, the Mexican bunkers were more depleted, so it was them losing the staring-down contest. In the event, US and German surveyors redrew the border to cut the gold deposit precisely in half (historic and geographical borders were obviously no relevant consideration), and everyone went home unharmed. Except the Portuguese, whose defeat helped spark the revolution of 1908, which would sweep away monarchy.

Mexican Empire:

B. Part II – 1891 to the Emperor’s death (1907)

8. Halcyon days

Although the clash with the USA had ended in President Harrison successfully bluffing Maximilian into abandoning his aspirations on the channel project, the Mexican Empire reached the peak of its internal popularity. Maximilian's image was not damaged by the defeat; the Mexican public had never wanted a war and was grateful when the Emperor chose peace over honor. Mexico's economy continued to prosper, fueled not only by private US and more or less private European investments, but also by increasing domestic activities, and the final decade of the 19th century was widely regarded as the country's golden era. Great improvements in health care drastically curtailed infant mortality and increased lifespan; between 1880 and 1915, the nation nearly doubled its population from 10.000.000 to 18.700.000. More Mexicans than ever received a share of the nation's wealth, and native Americans participated in a way that would have been unthinkable across the Rio Grande; during the 1890s, there even was substantial immigration to Mexico from Spain, Italy and the Habsburg Empire. Between 1880 and 1900, Mexico's GDP nearly quintupled from 6.200.000 to 29.400.000 dollars; that year, the per capita figure equaled Spain’s. Steadily increasing revenues enabled the emperor to keep nurturing his fleet; during Tegetthoff’s tenure as Minister of the Navy, the naval budget had quintupled, and in the 1890s, it doubled again. Even the teenage Infanta Isabel warmed to naval matters, in the shape of a handsome Lieutenant named Juan Alejandro Beltran, ten years her senior, who soon became her closest confidant and used imperial patronage to have himself promoted to Captain at age 27, Rear Admiral at age 31, Vice Admiral at age 35 and Full Admiral and Minister of the Navy at age 39. Only two generations before, Beltran’s grandfather had fought for the liberal rebels against the Empire (he was killed in action in 1866); now the family was staunchly monarchist, which was exemplary for most of Mexico’s bourgeoisie. Beltran was not only charming and charismatic, but also tirelessly energetic and became the dominating figure in Mexican naval affairs for nearly twenty years, although he never held a command at sea; the gallant but lazy Cordona quickly came to rely on him completely. In a completely different way, so did the Infanta. In 1896, she was married to a strapping German Prince named Karl August of Hohenzollern, the youngest son of Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, whose claim on the Spanish Throne had led to the Franco-Prussian war of 1871. Handsome and looking dashing in a uniform (which pretty much sums up his redeeming features), he became known in Mexico as Principe Carlos Augusto. On his departure, Kaiser Wilhelm II is reported to have said ‘He’s barking mad most of the time, and a scheming asshole in his lucid intervals. I hope they never give them any actual power,” which sums up everything else about him. Infanta Isabel detested her pompous and abusive husband from day one. Beltran on the other hand felt rather more enthusiasm for 'his' navy than for the Empress and played his relationship with the princess for all it was worth. He secured funds to improve training, doctrine, payment and living conditions for naval personnel, which quickly made him the most popular officer in Mexico’s armed forces. While he headed the materiel office in the Naval Ministry between 1893 and 1897, he turned to Great Britain as main supplier of Mexican ships, because Austria’s shipbuilding industry was not yet able to deliver what he wanted. Of the large 1892 fleet modernization program, two big pre-dreadnoughts, two armored cruisers and Mexico's first six real destroyers were British-built. A third battleship was acquired from funds of the program in 1895 from a British yard after the Chinese who had ordered it were no longer able to pay after their defeat against Japan in 1894. Austria was however not entirely sidelined; a coast-defense battleship was ordered in 1893, and the year after, the Tampico naval yard laid down a copy, which would become Mexico’s first domestically built capital ship. Of the four first class protected cruisers laid down between 1892 and 1898, three were Mexican-built, and only one was built by STT. The program also provided four gunboats and twelve torpedo boats. For the first time in Mexican naval history, warships were built in homogenous classes, and Mexican engineers and designers were sent to Great Britain to improve the capabilities of Mexico’s naval yards. While the navy prospered under Beltran, the 1890s also saw the rise of a much more malign figure, General Victoriano Huerta, who assumed the post of Chief of Staff of the Mexican Army in 1895 at age 45, and became its Commander-in-Chief in 1907. Like Beltran, he served under ineffectual superiors (first the honorable, but slightly senile Felipe Berriozabal until 1900, then the cultivated, but complacent Bernardo Reyes until 1910) and had de facto free reign long before he became Minister of war himself in 1910. Unlike Beltran, who was capable and ambitious, but not corrupt, Huerta – who was no bad soldier too, being an able organizer with a good grasp of technological developments, and a talent for asymmetric warfare – developed corruption from an art to a science. His efforts to increase the army budget always served his own interests, as he shamelessly enriched himself. Under his leadership, the Mexican Army was increased in numbers (by 1900, there was a standing force of 100.000), equipment and training, but it gradually lost its nature as an army of the people, becoming an instrument of suppression. It was almost ironic that the first conflict it fought under Huerta's tenure as Chief of Staff was a war of liberation.

9. More Spanish troubles

Popular resentment towards the increasingly inept, corrupt and brutal Spanish rule in Cuba had mounted during the 1890s till open conflict was inevitable. This resentment was shared by many in the USA, and the voices arguing for intervention became ever louder; on the other hand, the Spanish government’s notion of national honor categorically prohibited relinquishing control of their Caribbean colonies. The situation on the Philippines was quite similar, with open revolt against Spanish rule in progress, and the additional complication of Japan and Koko competing with the USA to aid the rebels. In Mexico, sympathies were divided. The Spanish were still profoundly disliked, and public opinion was all in favor of assisting secession of their remaining colonies in the Gulf and the Caribbean. On the other hand, the Imperial government understood that a war between the USA and Spain was a foregone conclusion; the inevitable US victory would not result in liberty for Spain’s colonies, but in a more efficient and powerful new ruler for them, which Maximilian’s advisors considered the worst case scenario. Retaining the status quo was considered preferable, and the Imperial government tried to moderate the boiling conflict between the US and Spain. Unfortunately, nobody listened, and the Americans sent their newest and most powerful battleship, USS Iowa, to Cuba in order to show their sympathies to the rebels. After Iowa had blown up in Santiago harbor on February 15th, 1898, due to decaying gun propellant, the Americans escalated tensions till Spain declared war on April 23rd, 1898. As early as May 1st, Spain’s naval presence on the Philippines was wiped out by the USN; the US fleet (battleship Oregon, armored cruiser Brooklyn and four smaller cruisers) hopelessly outgunned the local collection of Spanish unprotected cruisers and gunboats under Admiral Montojo. Spain focused all efforts on Cuba and sent every available warship across the Atlantic under Admiral Cervera. He could not prevent destruction of Spain’s scant naval presence at Cuba in a one-sided engagement off Guantanamo Bay on June 6th, but engaged the USN in a major battle on July 3rd off Santiago. The Spanish fleet, which had been at the nadir of its fortunes when Tegetthoff defeated it in 1885, had seen significant reconstruction and strengthening; corruption and inefficiency had been rooted out, fighting efficiency was much improved, and new equipment had been acquired. The battle of Santiago therefore was an unexpectedly even contest. The Americans fielded six battleships, an armored cruiser and five protected cruisers; the Spaniards brought five battleships, six large cruisers (four armored) and three smaller cruisers. Only the Spaniards had modern destroyers and torpedo gunboats; the US on the other hand had a dozen small torpedo boats. It was the largest engagement in the Americas since the War of Independence. Spanish total losses were higher than US ones, but only the Spaniards had 240mm rapid-reload guns on three of their ships, while the main guns of all US battleships were slow-firing. Peppered with multiple hits, all US battleships needed repairs, while those Spanish ships that had not been sunk were virtually undamaged. Having fought the USN to a stalemate at sea – for the time being; the Americans started to repair their ships within days of the battle – the Spaniards kept losing on land. They had not been able to prevent the insertion of an US volunteer force aiding the Cuban rebels, and the Rough Riders triggered uprisings wherever they went. Soon, the USA would be masters of Cuba, even without a decisive naval victory. In this situation, the Mexicans intervened and started to actively support Cuban rebels themselves, declaring war on Spain on July 18th. Only four days later, their fleet met the weakened Spaniards off Mayaguana. The Mexicans fielded four battleships, an armored cruiser, six smaller cruisers, two torpedo gunboats, six destroyers and twelve torpedo boats. Although the Mexicans lost an old ironclad to a magazine explosion, they sank a new Spanish battleship and a protected cruiser. The Spaniards – having been unable to resupply after their clash with the USN – were critically low on ammunition and had to break off the engagement. While they retreated to Santiago, the Mexicans coaled and re-supplied at sea – something nobody had believed they were capable of. A few days later, Prince Carlos Augusto himself landed at Guantanamo with a force of 4.000 well-armed volunteers. The Spanish base – heavily fortified at great expense during the last ten years and only recently opened – was taken without much resistance, the garrison fighting rebels deep in the island’s interior. President McKinley made the Mexicans aware in rather undiplomatic terms that the USA would not tolerate any Mexican land grab on Cuba, to which Mexico's foreign minister Miramon replied that Mexico had no intention to do that; all they were interested in was the end of Spanish colonial rule and freedom for everyone. Unfortunately, this was exactly what McKinley himself had been saying all along, so he could hardly admit he had never meant it seriously. Both sides thus kept fighting the Spaniards, secretly preparing to fight each other. On August 4th, US backed rebels unilaterally declared Cuban independence; Carlos’ Augusto’s proxies followed suit five days later. Town and port of Santiago went to open revolt. Without a base, the Spanish fleet needed to break out, with unrepaired damage to most of their ships and hardly any ammunition in the magazines. Just outside Santiago, the Mexicans were waiting, and the second battle of Santiago on August 15th went down a lot more lopsided than the first. Few Spanish ships made it to Puerto Rico; the Mexicans lost a protected cruiser and a torpedo gunboat. On land, things went less smoothly. So brutal was Carlos Augusto’s treatment of prisoners that the Spanish would fight him to the last cartridge; when the Rough Riders and their allies showed up, they’d just surrender. Ironically, many Cubans relished Carlos Augusto’s blundering more than Roosevelt’s sweeping success. In their lust for revenge, letting the Spaniards surrender and sending them home seemed less appropriate than torturing them to death. On August 20th, the last major Spanish garrison in Habana, out of provisions and stricken by yellow fever, surrendered to American-backed rebels. By that time, the US Pacific fleet was back from the Philippines, and some damage to the Atlantic fleet had been patched. When both fleets faced off near Cuba’s westernmost cape on August 27th, it was the Mexicans who were outnumbered and low on ammunition. The choice now was war against the USA or diplomacy. Maximilian and Miramon knew they stood no chance in a prolonged war and entered negotiations. Cuba became independent from Spain, the USA and Mexico promised each other to respect Cuba’s neutrality, and Spain had to cede Puerto Rico and the Philippines to the USA. The fortress of Guantanamo was closed and its heavy guns disabled (the Mexicans however secretly purloined their breechblocks for possible later use). Carlos Augusto was greeted a hero in Mexico, fueling his already huge self-image beyond the threshold of megalomania. The Americans meanwhile occupied Puerto Rico; the remnants of the Spanish fleet had already left. They also annexed Hawaii, which alarmed the Japanese, who had been working towards establishing a protectorate of their own over the archiple with its large population of Japanese immigrants. Japan and Koko reprocitated by arming and encouraging Filipino nationalists to take up arms and fight for full independence. A heavy-handed and rather clumsy American crackdown resulted in a full blown war, which raged from 1899 through 1902, claiming almost 200.000 Filipino lives. When Japanese arms deliveries to the rebels were uncovered, the USN blockaded the Philippines, resulting in several face-offs with Japanese warships. All-out war could be avoided by British diplomatic intervention, but the episode sparked considerable anti-American bitterness in Japan and Koko, which would result in severe repercussions two decades later.

10. Emperor sees 20th century, doesn’t like it, dies

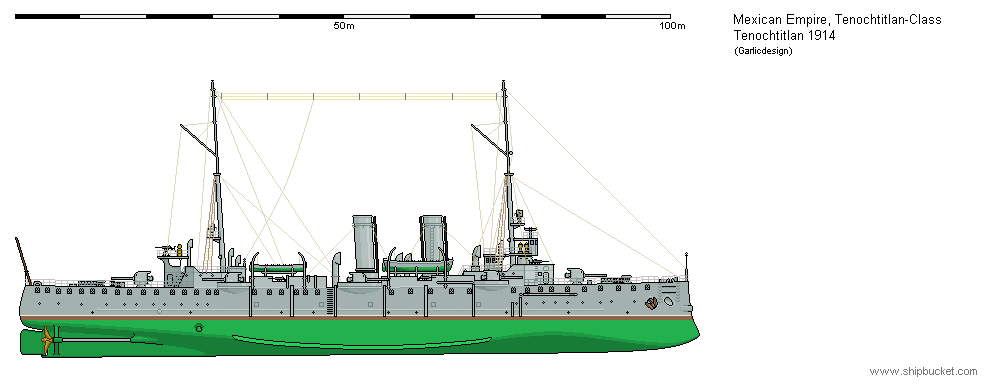

When Carlos Augusto returned to Mexico, he celebrated the first Mexican victory on land against an external enemy since the 1820s. General Huerta however knew that Carlos Augusto had not paid the price for his force’s deficiency in equipment and training only due to the weakness of the opposition. In the following years, Huerta managed to scrape off a larger part of the defense budget for itself and buy modern heavy equipment (and a large estate for himself, of course). Discipline of the army was rigorously enforced, but training and doctrine remained old-fashioned, logistics were neglected, and payment of ratings, noncoms and junior officers was only a third of what could be earned in the navy. Although the navy had dominated the Spaniards, its funding decreased in the years after the war. As General Huerta put it, the navy had performed flawlessly after all, and did not need further improvement. Instead, Huerta oversaw construction of two huge arms manufacturing complexes at Mexico City and Guadalajara; the former made guns of up to 150mm caliber under Skoda license, the latter made the ammunition for them. Another company founded by Huerta made the famous Mondragon rifle, the world’s first semi-automatic weapon to be adopted as service weapon by the Imperial Marines (it was also license-made in Germany during the First World War). Although these factories needed state subsidies throughout their existence, any profits generated of course largely went to Huerta’s personal pockets; navy orders in particular were grossly overcharged. With economy entering a phase of stagnation - attempts to 'Mexicanize' the economy and reduce the influence of foreign, especially American, investors had scared foreign capital off - the beginning of the 20th century marked a period of erosion of imperial authority in Mexico. German investments never were large enough to make up for the loss of US dollars, and German businessmen acted as undiplomatic as their US pendants, and then some. Worse, their arrogance was laid at Prince Carlos Augusto’s door, who was one of them, after all. Being himself, Carlos Augusto did little to improve his public image. His notion of marital fidelity was no more sincere than that of the Empress, if rather less discreet and considerably more profligate. He displayed contempt of Congress and everything that passed for democratic institutions in the Empire, and his attitude towards indigenous Americans, Afro-Americans and Jews would have earned him a place at the Wannsee conference. With Carlos Augusto's backing, General Huerta, who saw communist insurgence everywhere, tirelessly worked to transform Mexico into a police state. To regain some popularity, the Emperor signed a constitutional reform giving Congress more power in 1901; in many respects, Mexico's constitution of 1902 was more democratic than Germany's or Austria's. Rather than smoothing over the discontent, this new freedom only made the opposition bolder, resulting in increasing reluctance to vote money to the armed forces. Between 1897 and 1907, only a single battleship, three cruisers and four destroyers were approved, plus six gunboats, to keep the shipyards occupied. The Emperor - urged by the Infanta, for obvious reasons - had Beltran appointed Minister of the Navy in 1902 upon Cordona's retirement. In the first five years of his tenure, he had to work with reduced budgets, but still managed to bolster naval infrastructure. A torpedo manufacturing plant was opened at Veracruz in 1908, and the Tampico navy yard received a plant for manufacturing Schulz-Thornycroft boilers under license in 1911. Beltran also struck a deal with Siemens to construct a factory for turbines and electric engines in Monterey, which opened in 1913, and with MAN to build a plant for diesel engines at Queretaro, which opened 1914. A submarine construction plant was added to the Tampico naval yard and became operational in 1913. These measures enabled Mexico to build submarines and surface ships of cruiser size without imports; the only items not manufactured domestically were heavy armour plate and naval guns of more than 150mm caliber. Beltran also ensured regular payment of his crews and kept the available ships in prime condition. Large exercises were conducted and constant contact with foreign navies was maintained in order to further develop tactics and doctrine. A German naval mission from 1905 through 1909 under Captain Wilhelm Souchon, the future C-in-C of the Ottoman Navy, helped the Mexicans acquire night-fighting proficiency, perfect their maintenance routines and oversee their design requirements. Mexican warships regularly visited Britain, Brazil, Germany and Austria, and many Mexican officers were sent to train abroad. Actual combat deployments during this period were rare; the Mexicans tried to intervene several times when central American nations ran into trouble, but they invariably ran into the USN. Only rarely did they achieve their objectives. The most positive example was the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902, when several European powers blockaded Venezuela’s coast to enforce the payment of debts. Although Maximilian and especially Carlos Augusto favored the European (particularly the German) position, Mexican public opinion supported the Venezuelans in this affair, and the Imperial government was determined to settle things diplomatically before things spiraled out of control and the US ‘saved’ Venezuela the same way they had saved Puerto Rico and the Philippines. A force of two armored and three protected cruisers under Rear Admiral Greifenstein was a powerful backup in achieving a negotiated settlement. Mexican involvement enabled the Germans to give up their stubborn (and slightly stupid) all-or-nothing stance without significant loss of face, masking their withdrawal as honoring a personal plea from the brother of their closest ally. During the 1903 Panama crisis, when the Americans enforced the independence of Panama from Colombia, the Mexicans again dispatched Greifenstein with a sizeable squadron, this time including two battleships, which however faced a superior US fleet and wisely took no action that could be construed as provocative, because Roosevelt had repeatedly pointed out that he only waited for an excuse. The only positive result was a strengthening of relations with Colombia; like Venezuela, the nation could be considered an informal Mexican ally afterwards. From that point, the Americans increased their presence around the Caribbean. In order to kill further crises like the Venezuelan one in their cradles, they would intervene militarily as soon as any Central American nation experienced financial troubles or threatened to become unstable politically. Or if they struck major treaties with Mexico, which the White House reliably interpreted as a surefire sign of impending financial troubles and political instability. The result was inevitably a new government prioritizing US interests over anyone else’s. This happened in the Dominican Republic in 1904, in Nicaragua in 1905 and on Cuba in 1906. Mexican attempts to intervene were met with overwhelming force and thundering threats of total war and hellfire. In all three cases, the Mexicans had to back off, losing face every time (which was an actively pursued secondary objective of the Americans, every time). Roosevelt actually seemed to enjoy driving old Maximilian to conniptions that way; his own popularity certainly profited from his playing hardball with the Habsburgs. On the other side, the series of foreign political humiliations took their toll on Maximilian’s health, and between 1904 and 1907, the Emperor suffered three strokes. The second one permanently incapacitated him, and the third one, suffered on February 5th, 1907, killed him, aged 75. Roosevelt condoled the Mexican people with the remark that now the 20th century could begin for them.

11. Other People’s scores

In mid-1906, a Portuguese-owned limber company operating in the Amazonas rainforest close to the Venezuelan-Brazilian border accidentally discovered a major gold deposit and started to clandestinely ship mining gear down the Orinoco. When the Venezuelans found out, they nationalized the mine, and the company went bankrupt early in 1907. The Brazilian government consulted a map and found the border in that area had never been properly surveyed. That omission was made good during March 1907, to no-one’s surprise placing the mine squarely on the Brazilian side of the border. The Venezuelan government was told to vacate the area and leave behind the confiscated mining equipment, or else. Venezuela reacted by moving in troops; the resulting clash between Venezuelan regulars and Brazilian border guards in June 1907 ended with a not entirely surprising reverse to the Brazilians and a formal declaration of war. While the Brazilian army prepared to move in with overwhelming power, their navy deployed two battleships and three cruisers to blockade the Venezuelan coast. Simultaneously, the Portuguese government informed the USA that they would deploy forces of their own to Venezuela in order to reclaim Portuguese property. Since the events of 1903, President Roosevelt considered the Venezuelan government a major nuisance, and in his quest to improve relationships with Great Britain – which had somewhat suffered from his fleet building spree – he picked the side of Great Britain’s ally Brazil. Moreover, Portugal – also a British ally – was no power of any significance, so the Monroe Doctrine would not suffer too much from whatever modest forces the Portuguese could contribute. Roosevelt told the Portuguese they could attend if they placed themselves under Brazilian command, which he secretly hoped their national pride would prevent. Surprisingly, the Portuguese acquiesced and deployed a battleship, a cruiser and a destroyer to the Caribbean, placing them under overall command of the Brazilian Admiral Julio Cesar de Noronha. The Venezuelan government, not possessing any navy worth mentioning, secretly asked the Mexican government, who had saved them before, for help. With Maximilian dead and his sole daughter Infanta Isabel uninterested in Politics, Prince Carlos Augusto convinced the government to leap to the opportunity, as the Americans were obviously intending to let the Venezuelans be walloped. Admiral Moya sailed with two battleships, two armored cruisers, four protected cruisers and eight destroyers; on August 16th, 1907, he reached the Brazilian-Portuguese blockade position off La Guaira and told Noronha to sod off. Simultaneously, the Imperial government publicly declared its support for the Venezuelan cause and called for an international conference to settle the issue. President Roosevelt, who had not taken the issue too seriously, went to red alert. This was not what he had planned. The USN, which was currently preparing for the cruise of the Great White Fleet, was told to dispatch a squadron of the newest Conneticut-class battleships under Admiral Sperry, plus appropriate cruisers and destroyers, from Norfolk to La Guaira. While announcing the move, Roosevelt offered the service of the best surveyors in his pay in order to impartially determine the correct location of the border (meaning, exactly where the Brazilians had placed it). Anyone disagreeing – especially the Mexicans, for whom the whole affair was none of their business anyway – would have to face Admiral Sperry’s guns. As soon as this statement was out, Noronha gave the Mexicans six hours to retreat, or face the consequences. He was sure they would cave in. Both fleets were of approximate equal strength, and American reinforcements were under way. The old Emperor would have called it quits at this point, but he was dead, and Prince Carlos Augusto fancied himself made of sterner stuff. He told Admiral Beltran to order Moya to break the blockade, and send him another two battleships as reinforcement. Engaged separately, the Brazilian squadron could surely be defeated before the Americans were there; in the meantime, the Venezuelans could be provided with weapons and ‘volunteers’ to force the issue against the Brazilian army. When Beltran asked the Infanta for confirmation, she absent-mindedly gave it, while still incapacitated with grief over the Emperor’s death. True to Beltran’s orders, Admiral Moya let the ultimatum lapse, challenging the Brazilians to do something about it. Noronha, who was under orders not to risk unnecessary losses due to the critical situation on New Portugal, which could spark a war with Thiaria at any time, got cold feet and ordered his fleet to open the distance, but the commander of the Portuguese contingent, gung ho to uphold his nation’s honor, refused to back down and opened fire upon the Mexican vanguard. After half a bloody hour, the Mexicans had sunk all three Portuguese ships, without the Brazilians lifting a finger. Noronha retreated to the north-east and the blockade was lifted. Carlos Augusto was exultant, and at Veracruz, five transports were laden with guns and ammunition for Venezuela. The next day, the Mexican cruiser Zaragoza entered La Guaira to a frenetic welcome. Another two days later, the Americans met the Brazilians, and both fleets headed for the showdown off La Guaira. Neither the Mexican reinforcements nor any of the transports were anywhere near, and it was painfully obvious that Carlos Augusto had overplayed his hand. As the Imperial government frantically sought for a way out of the conundrum, the ambassadors of friendly nations were contacted. When both fleets already circled each other, the Kaiser, of all people, cabled an offer to send surveyors of his own, to work together with the Americans and attain a truly impartial result which would be acceptable to both sides. The Imperial government jumped at that solution and unilaterally accepted it; neither Carlos Augusto, who wanted to slug things out, nor the Venezuelans were consulted. President Roosevelt was of one mind with Carlos Augusto this time and wanted to force the issue, but the Brazilian government – fearing Thiaria might take advantage of any Brazilian entanglement – caved in and accepted the German offer as well. This development rendered the Americans in the absurd situation of being the only ones not interested in a peaceful settlement. Roosevelt badly wanted to sink the Mexican fleet, but he needed them to fire the first shot; unfortunately, they no longer had any reason to do so. At that point, childish as it was, it was only a question whose fleet retreated first. Having been on station longer, the Mexican bunkers were more depleted, so it was them losing the staring-down contest. In the event, US and German surveyors redrew the border to cut the gold deposit precisely in half (historic and geographical borders were obviously no relevant consideration), and everyone went home unharmed. Except the Portuguese, whose defeat helped spark the revolution of 1908, which would sweep away monarchy.

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Mexican Empire 1861 - 1916

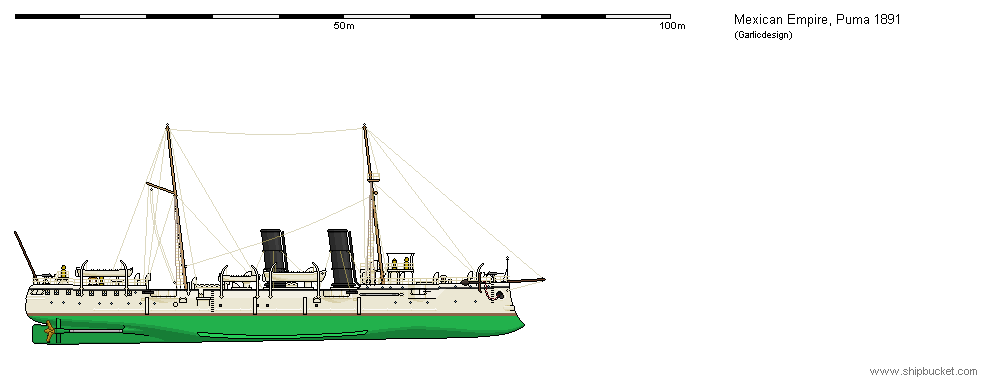

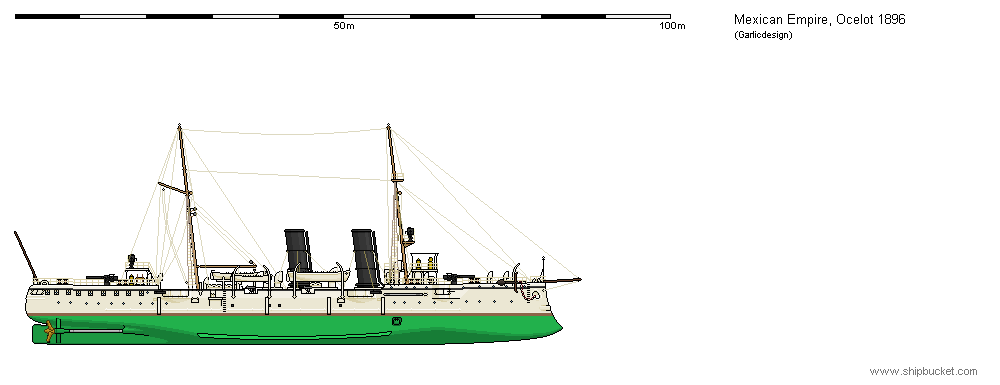

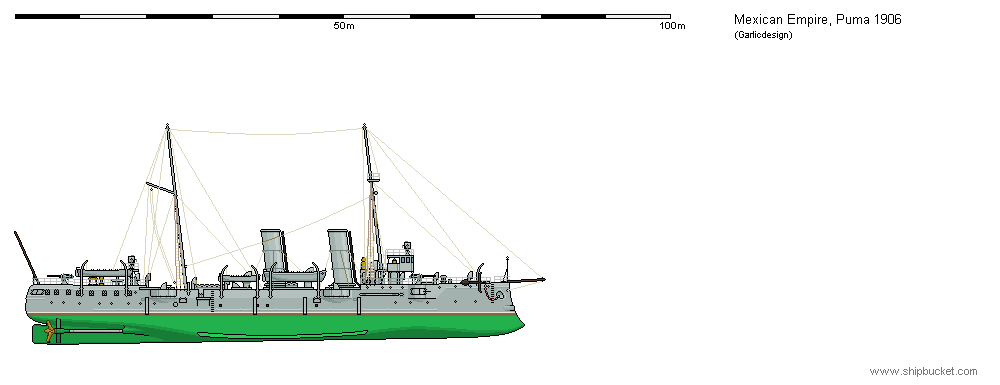

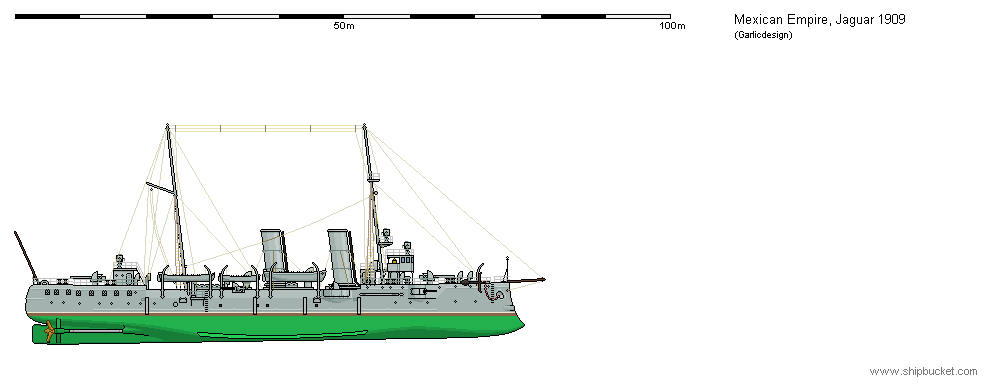

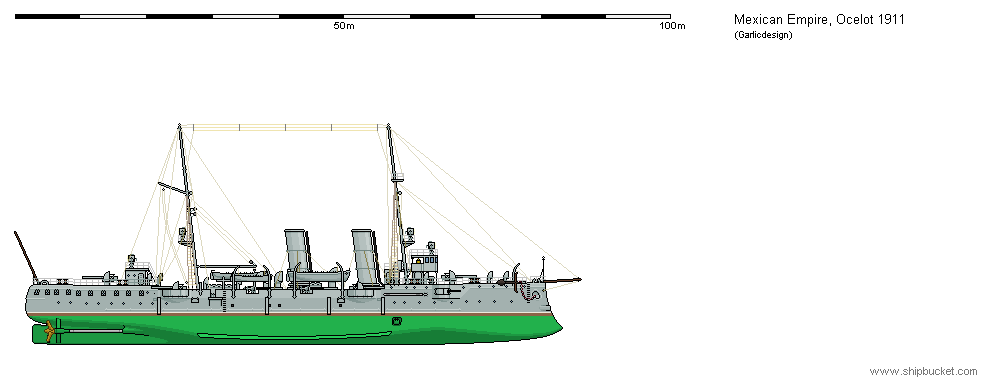

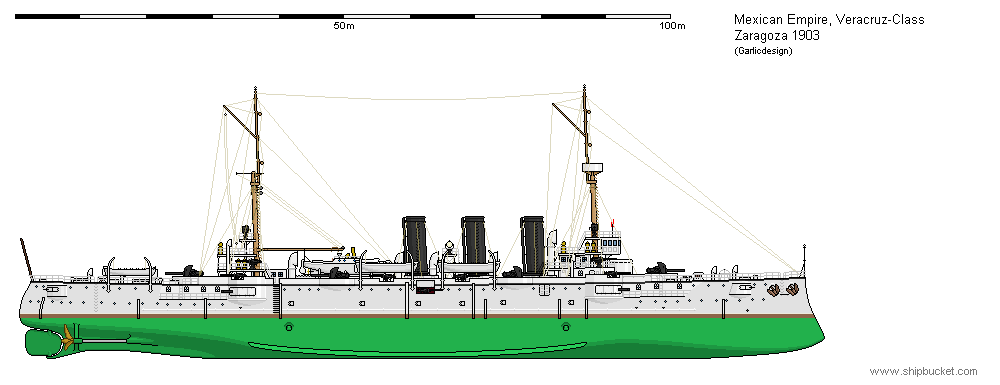

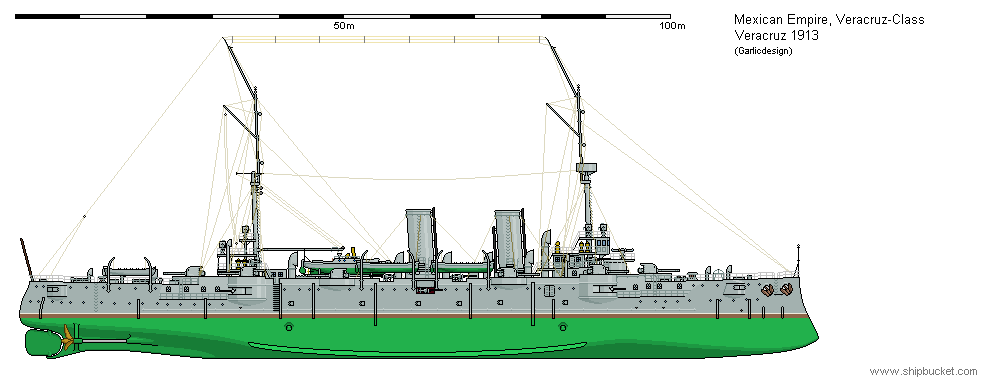

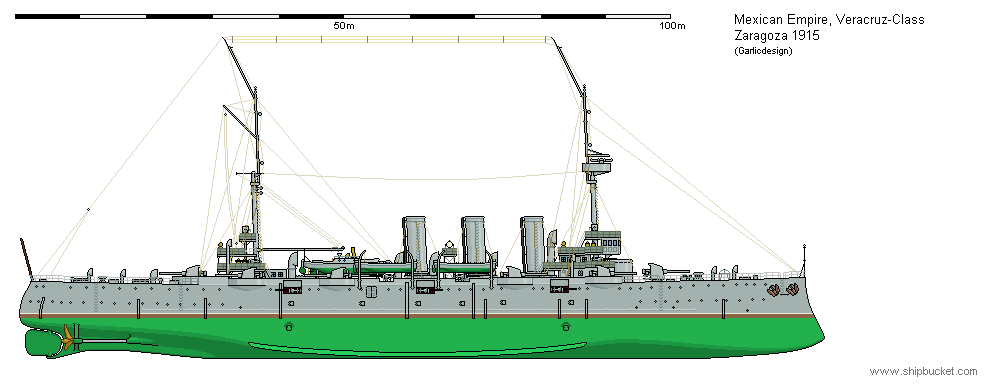

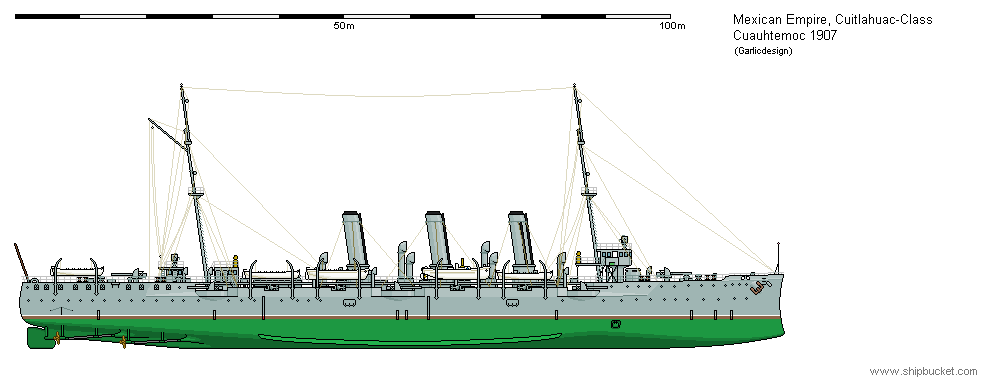

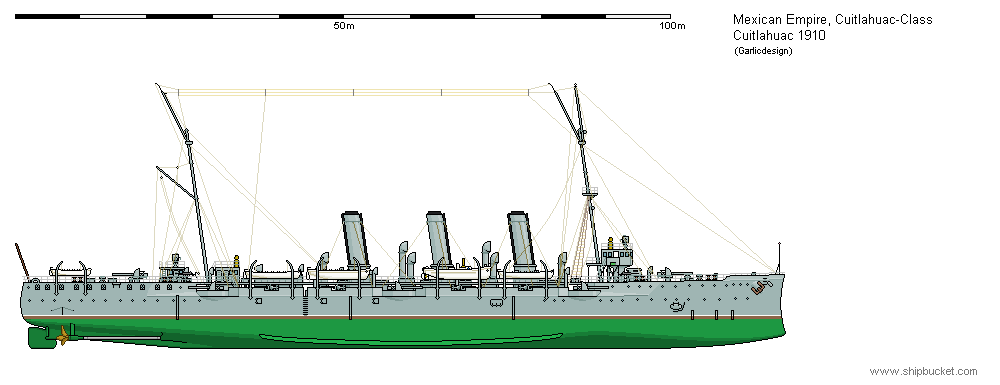

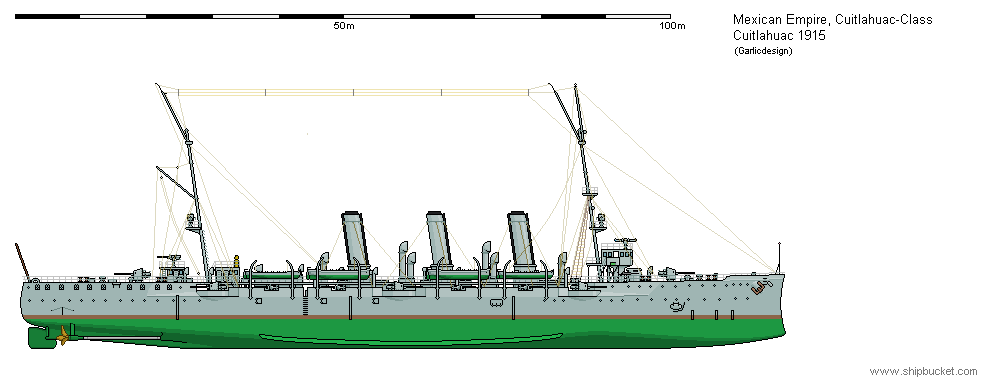

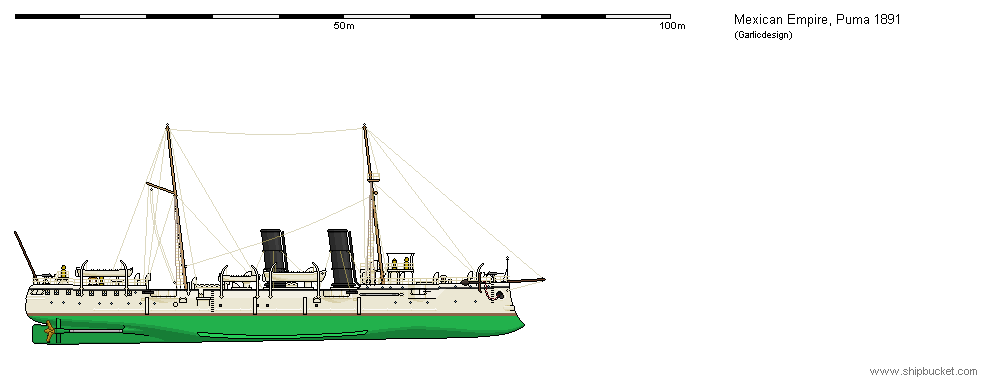

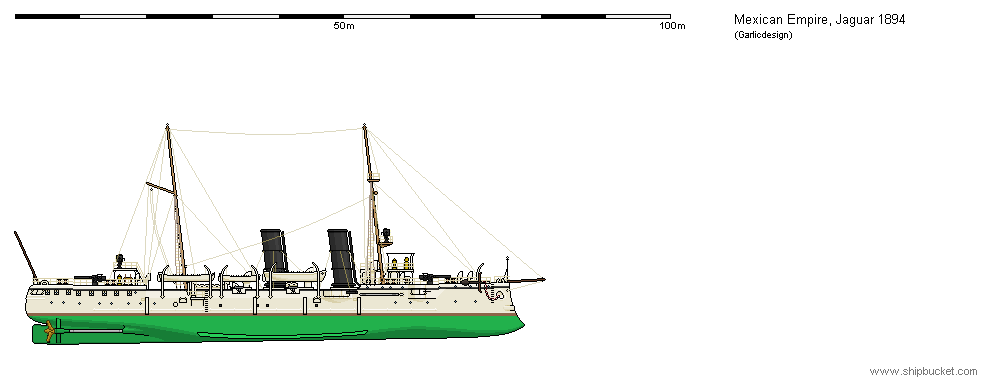

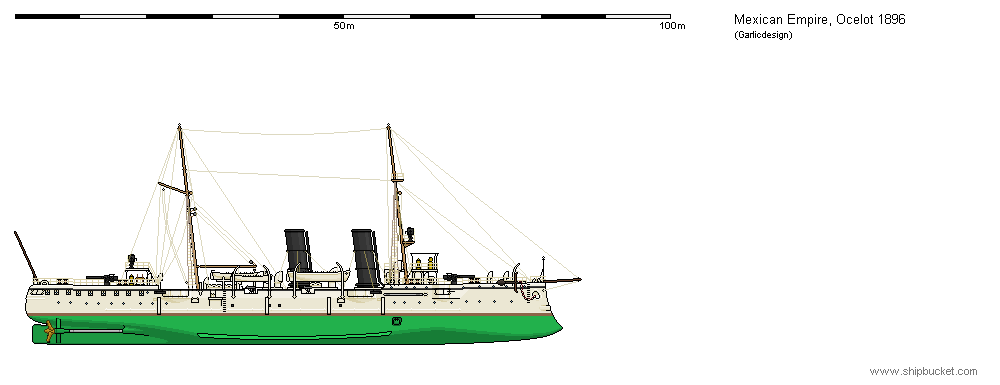

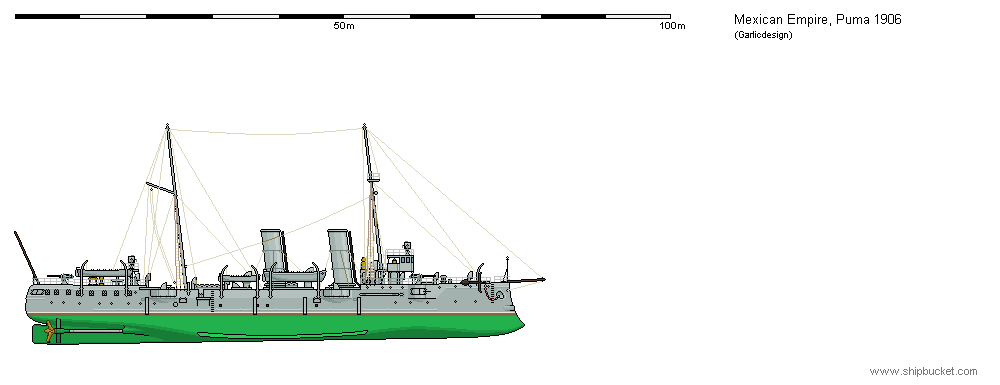

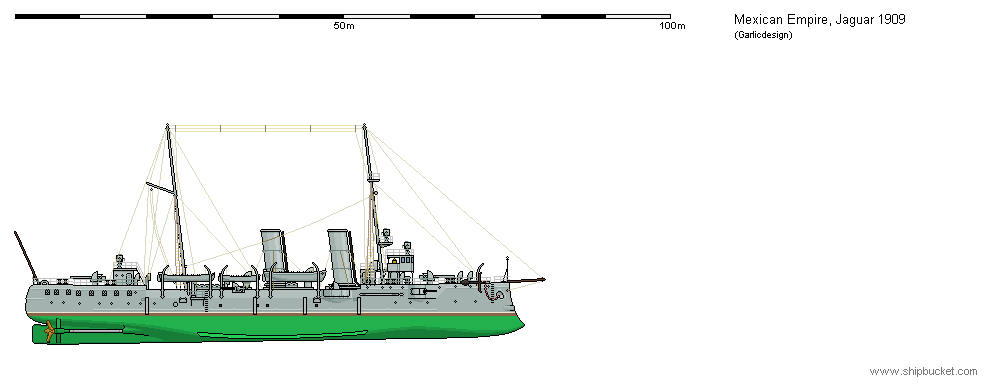

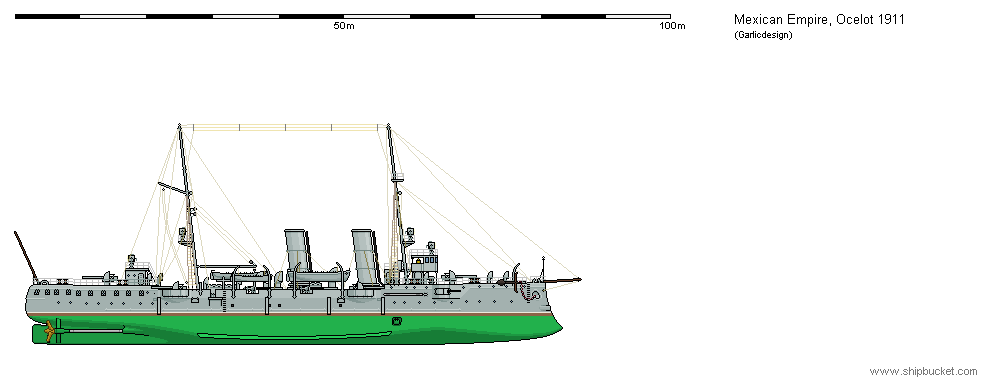

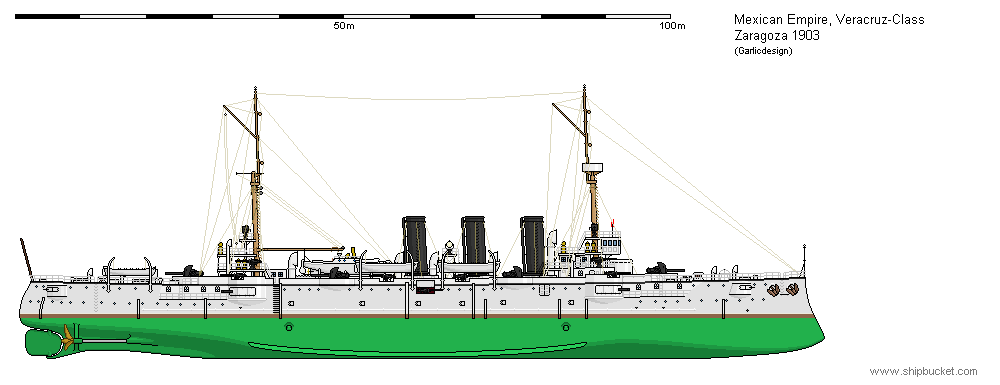

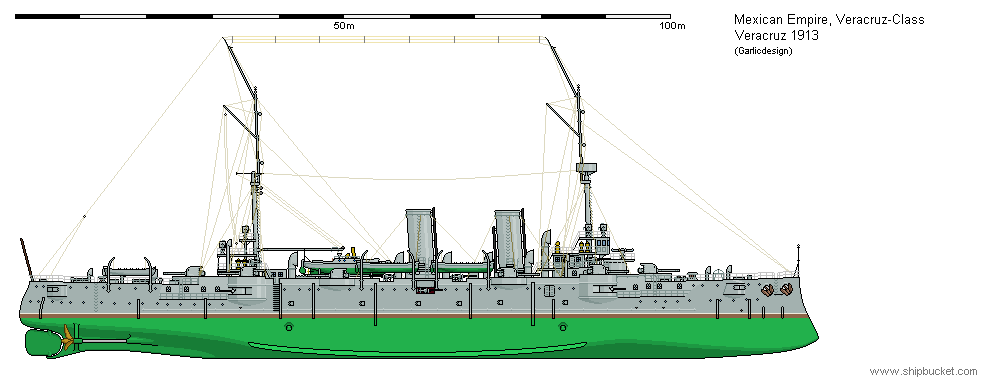

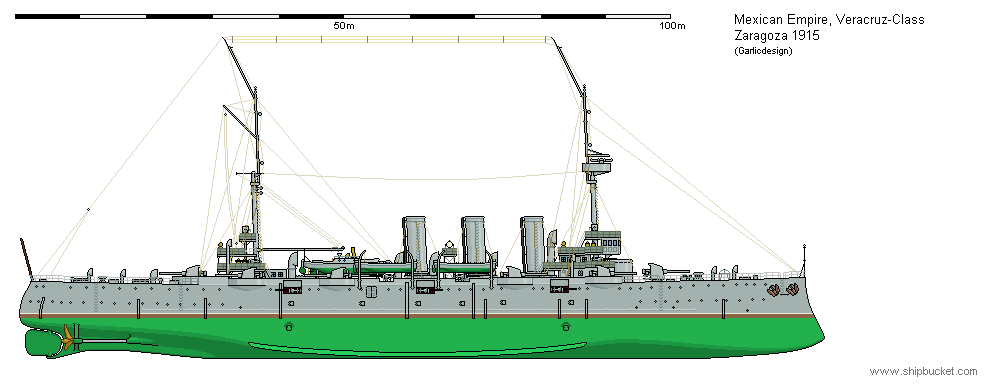

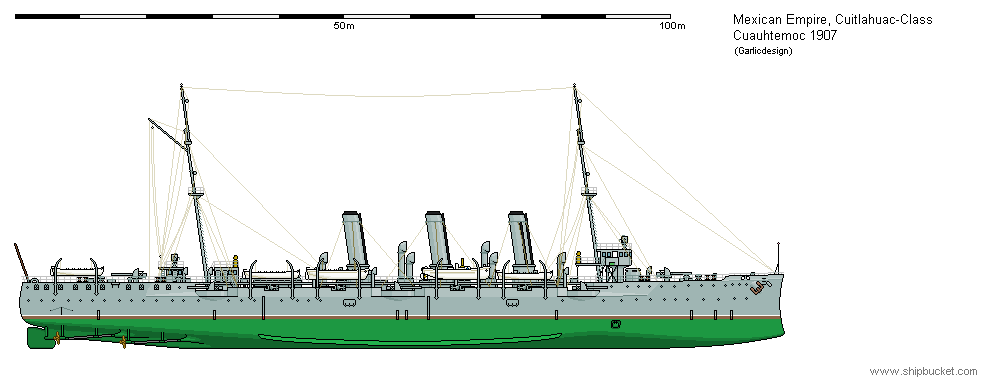

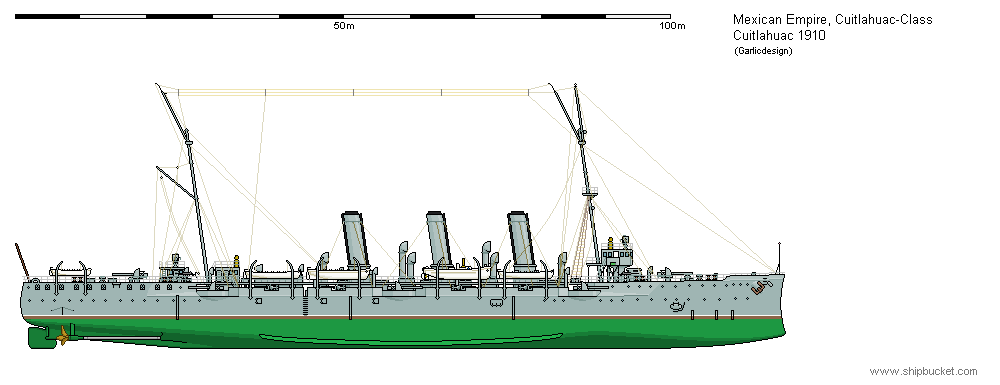

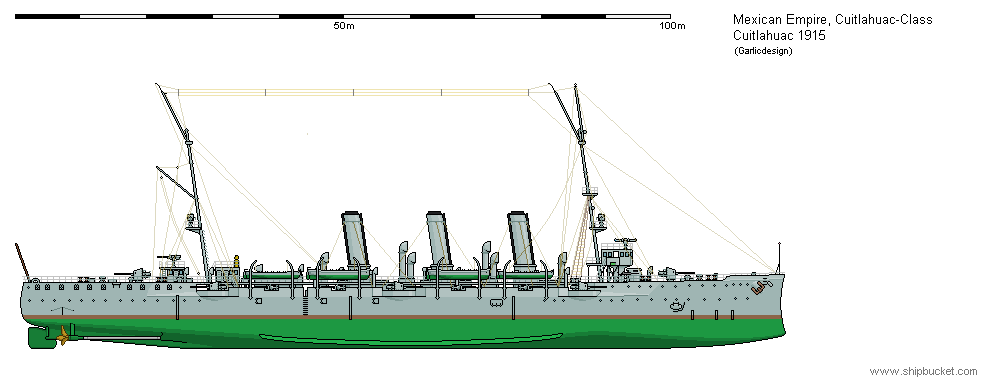

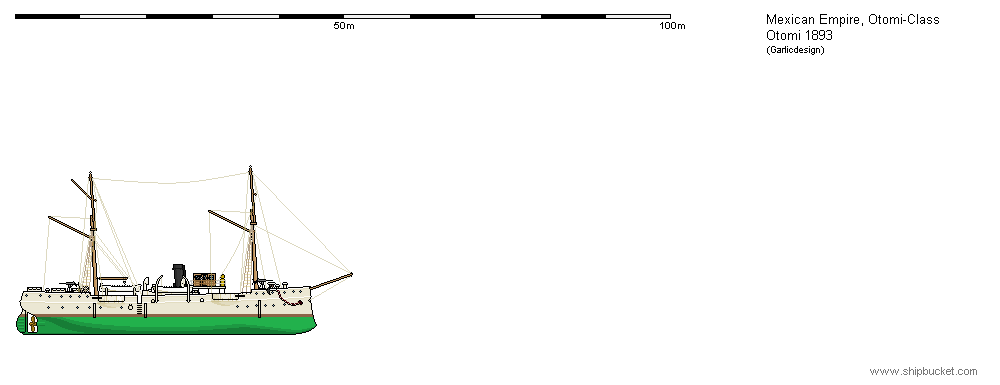

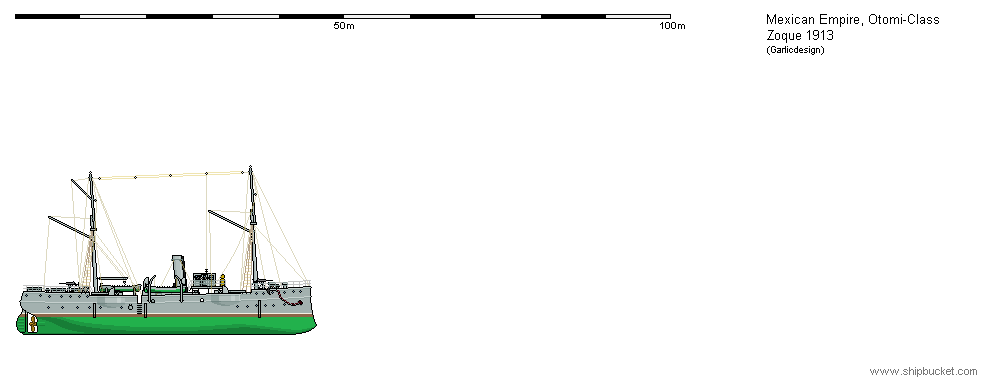

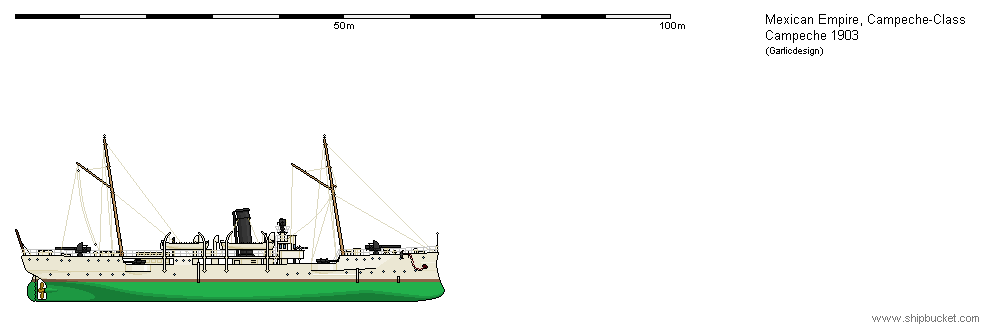

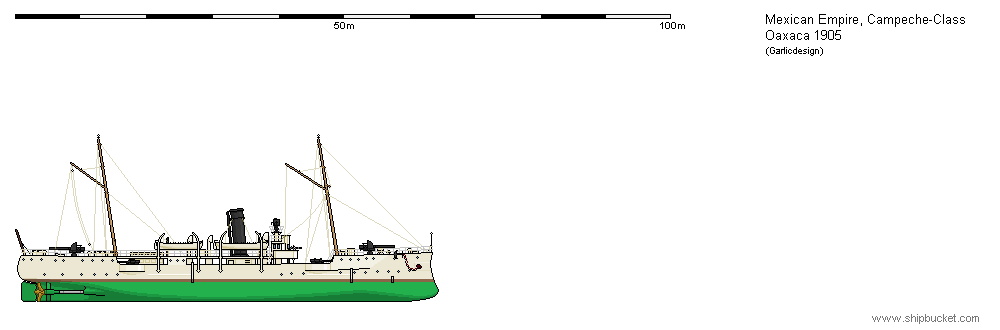

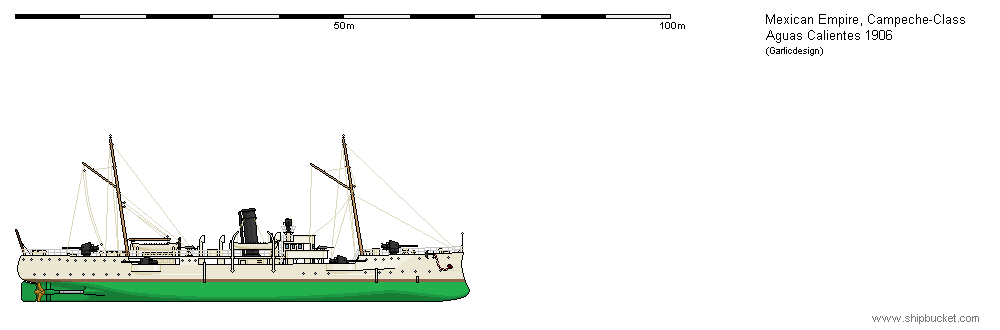

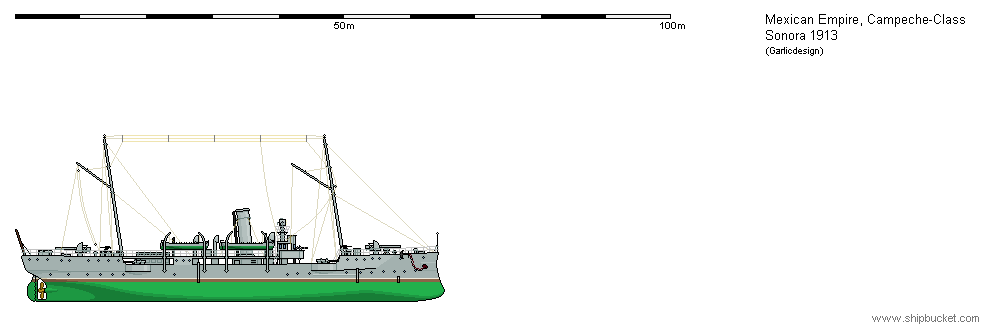

Mexican Warships 1891 – 1907

A. Battleships

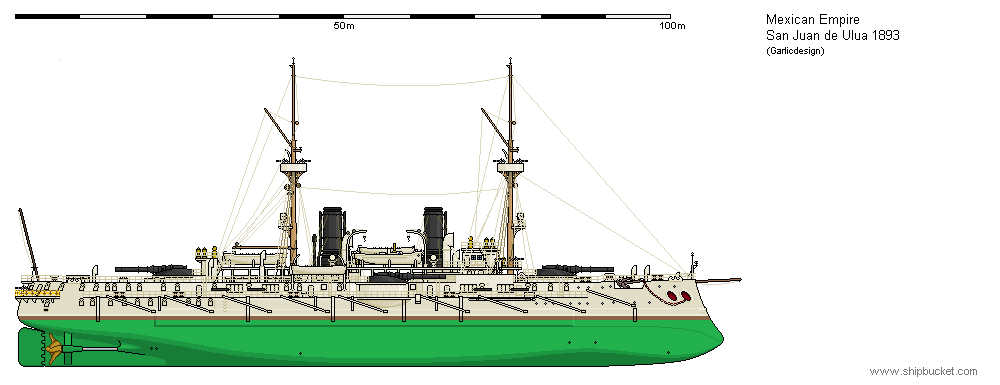

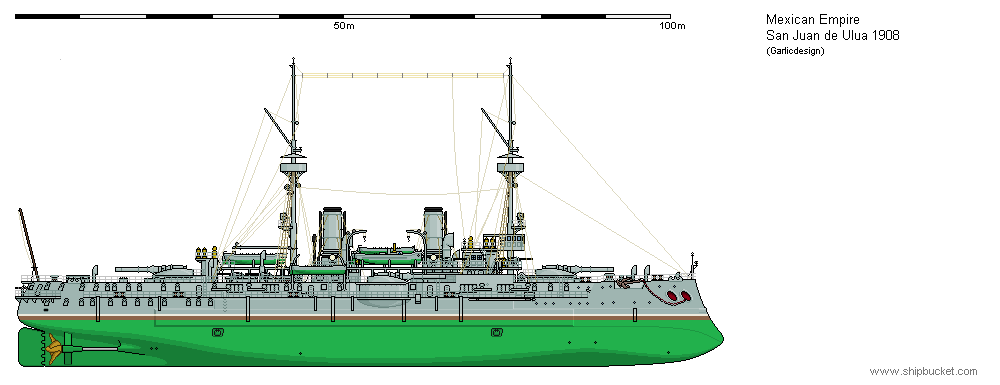

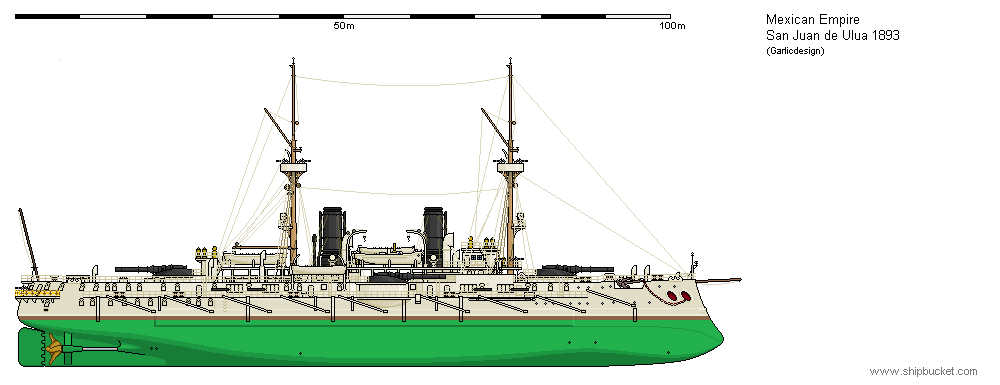

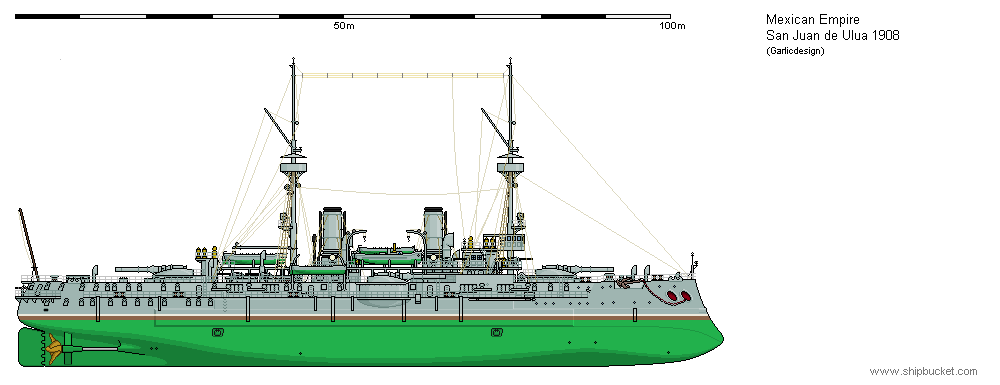

1. San Juan de Ulua

This unique vessel bears the distinction to be the first battleship tailor-made to a Mexican requirement. While Rio Brazos was mostly Tegetthoff’s brainchild, San Juan de Ulua incorporated design input by his Imperial Majesty himself. Maximilian embraced ramming tactics as much as Tegetthoff, but wanted more flexibility; he rightfully considered Rio Brazos as a single-mission hull of limited usefulness in a contemporary battle. He stipulated twice the main armament, arranged in a way to provide three barrels in any possible direction, as in contemporary French ships. The secondary armament was augmented to eight barrels, four on each broadside in a thinly protected battery, and the armored belt was extended upward and forward to close the gap between main belt and battery and give the ram a better structural foundation. Speed was set at 17 knots, the same as Rio Brazos (although the speed was not achieved in service). These improvements needed space, and the final design exceeded 10.000 tons, best compared to the Spanish Pelayo-class or the French Marceau-type. When she was ordered at STT in 1887, she would have been the first ship in the New World of that size; in the event, the Thiarian Ardcheannas, which was ordered later, but completed earlier, narrowly beat her as the largest warship in the Americas. The ship was named for a victorious battle during the Mexican War of Independence against Spain.

Displacement:

10.340 ts mean, 11.600 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 107,75m, Beam 20,70m, Draught 7,15m mean, 7,95m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Compound, 12 cylindrical boilers, 10.000 ihp

Performance:

Speed 16,5 kts maximum, range 2.400 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Compound. Belt 280mm; forward end 170mm, aft end unprotected; Barbettes 280mm; upper belt and battery 170mm; deck 40mm maximum, CT 170mm

Armament:

4x1 305mm/35 Krupp BL, 8x1 150mm/35 Krupp BL, 10x1 47mm/33 Hotchkiss revolver, 4x 450mm Torpedo tube (1 forward, 1 aft, 1 on each beam, all above water)

Crew

590

San Juan de Ulua was laid down early in 1889 at Trieste and delivered late in 1893. She was fleet flagship between 1894 and 1898; the flag was transferred to Poder days before the Second Spanish war. Together, both ships formed the first division and spearhead of the Mexican fleet. San Juan de Ulua successfully took part in every engagement of that war and was credited with sinking the new armored cruiser Cataluna during the second battle of Santiago.

After the war, San Juan de Ulua was quickly rendered obsolete by contemporary battleship design abroad. Nevertheless she was a reliable ship with a good availability rate and a well-trained crew; she represented Mexico at Queen Victoria’s diamond Fleet review at Spithead. She also was involved repeatedly in face-offs with US naval forces during several US intervention missions in various Central American nations throughout the 1900s. In 1910, she followed Poder as the second Mexican capital ship to be equipped with w/t gear; during this refit, she also landed her torpedo nets. Her bridge was augmented, and her 47mm guns were replaced with eight modern 66/50 Skoda QF guns.

Late in 1912, San Juan de Ulua traveled to Trieste, where Mexico’s first dreadnought battleship was pending delivery, carrying 300 reservists; her own crew transferred to the new Emperador Maximiliano, and San Juan de Ulua was brought back to Mexico by the reserve crew. Afterwards, she remained in reserve at Veracruz. In 1915, she was hulked and served as administrative flagship of the commandant of the naval base there. She survived the war against the USA without seeing action, but during the Mexican civil war, she was sabotaged by communist insurgents (former navy sailors) and sank on an even keel in March 1917. She was refloated in 1920 and scrapped.

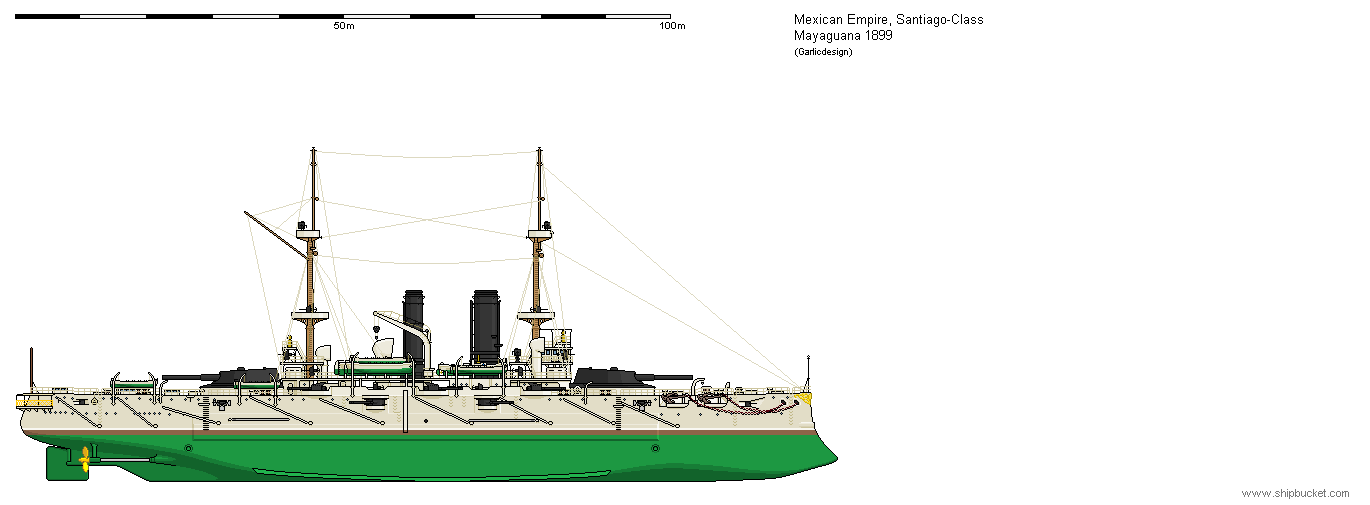

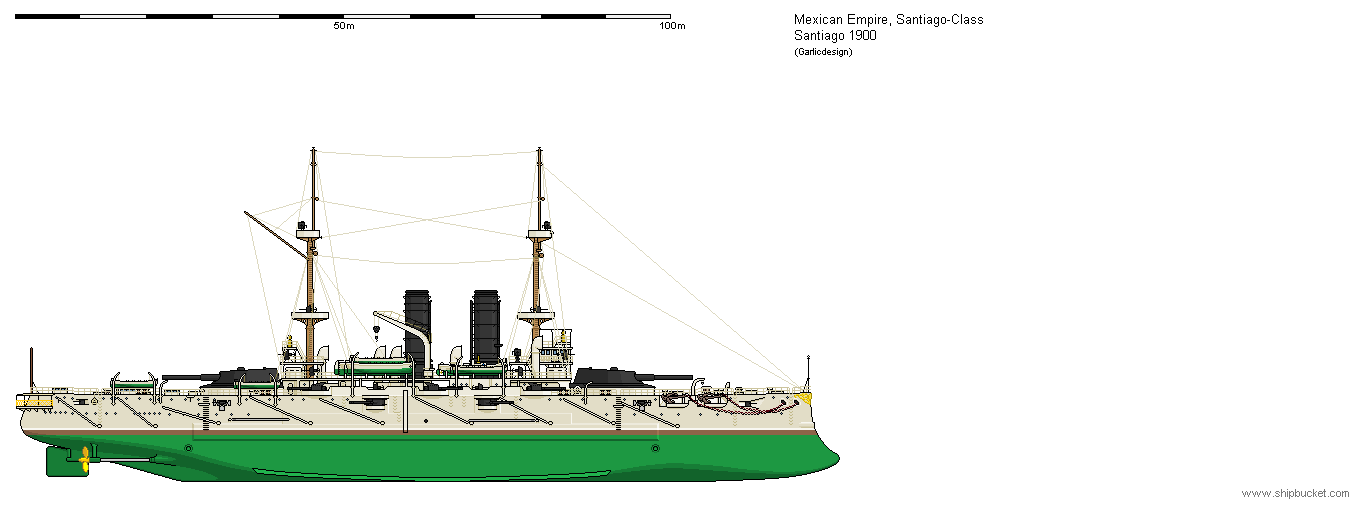

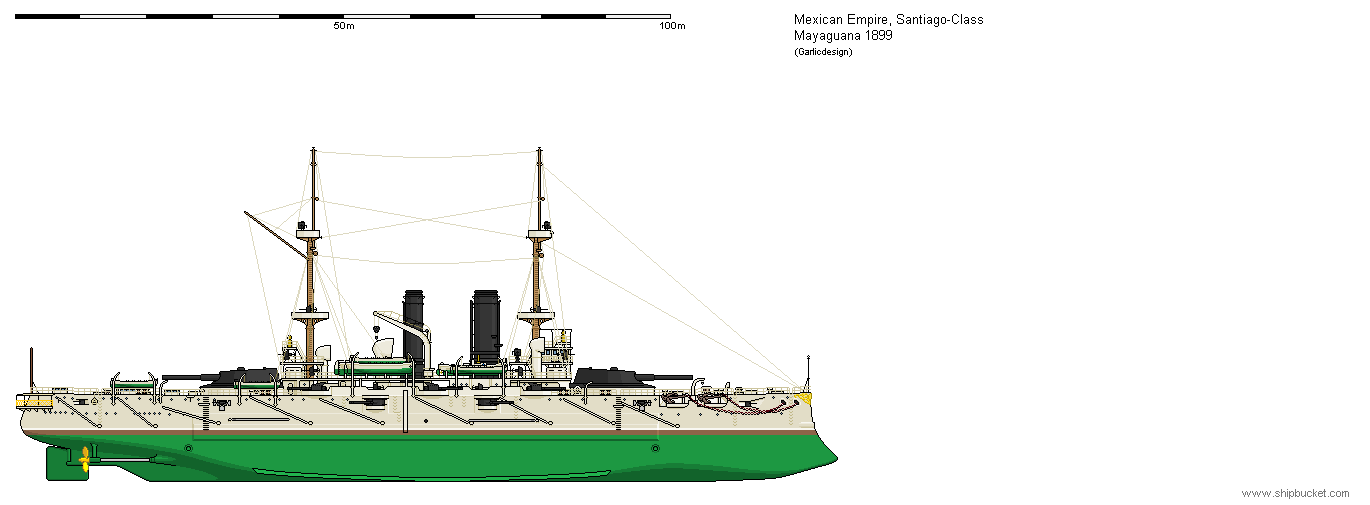

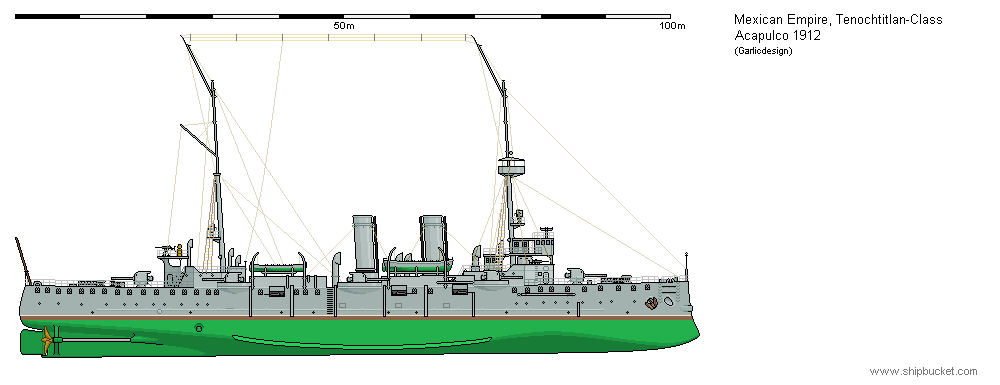

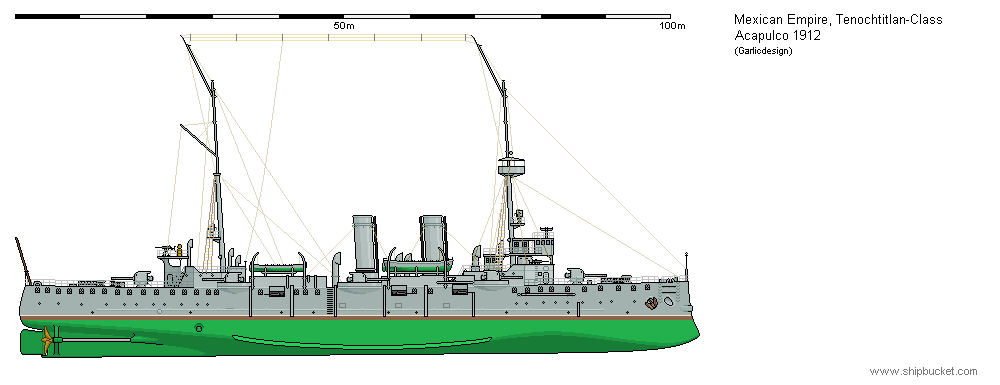

2. Mayaguana-class

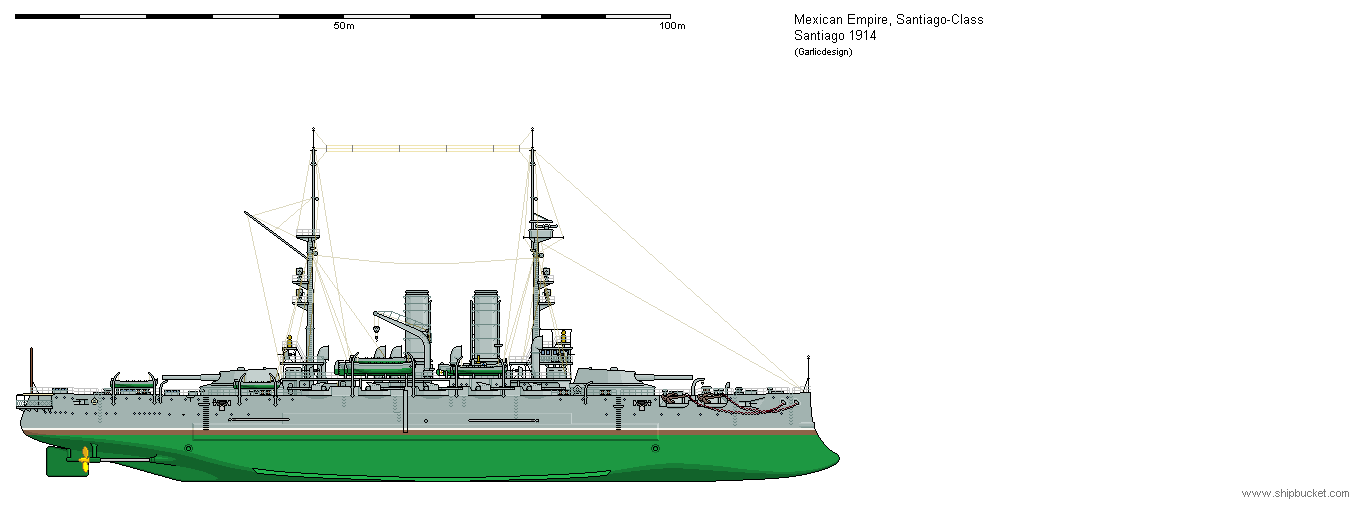

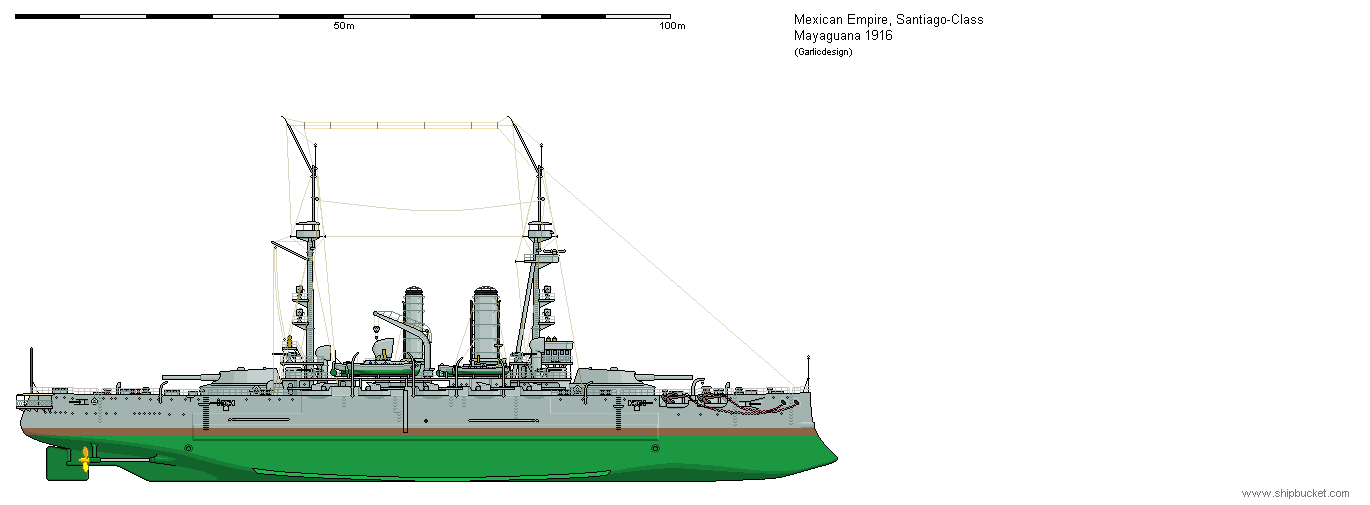

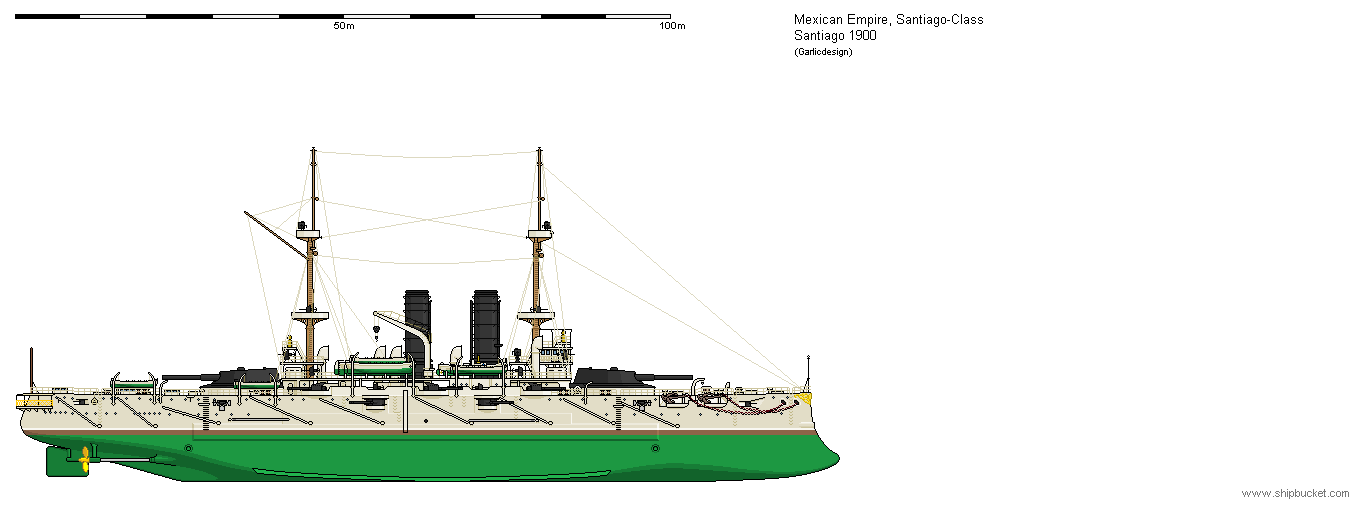

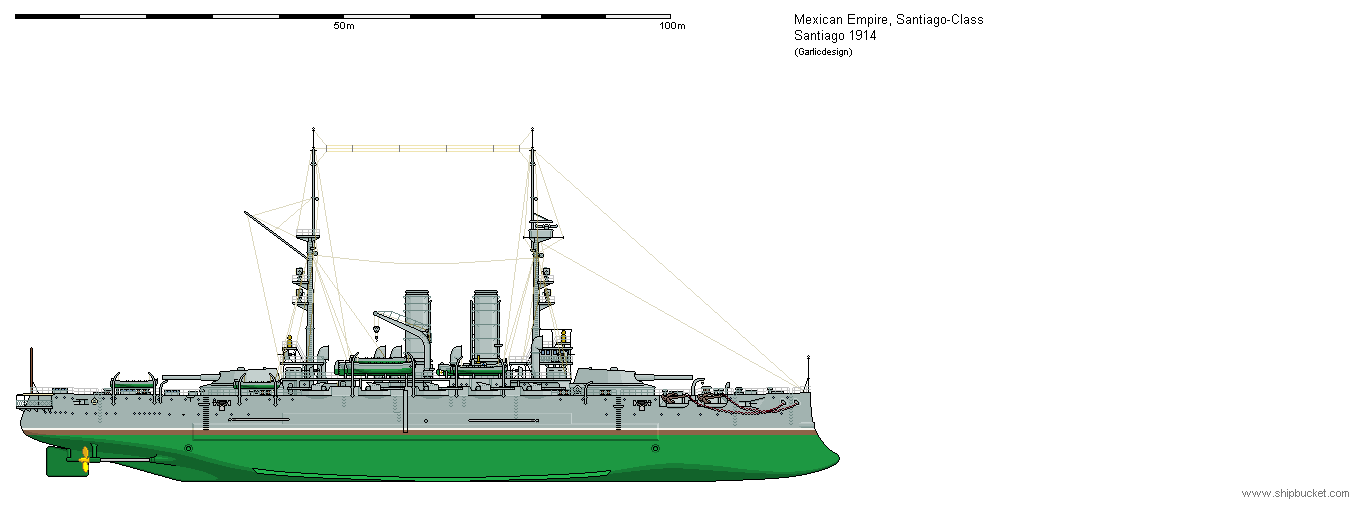

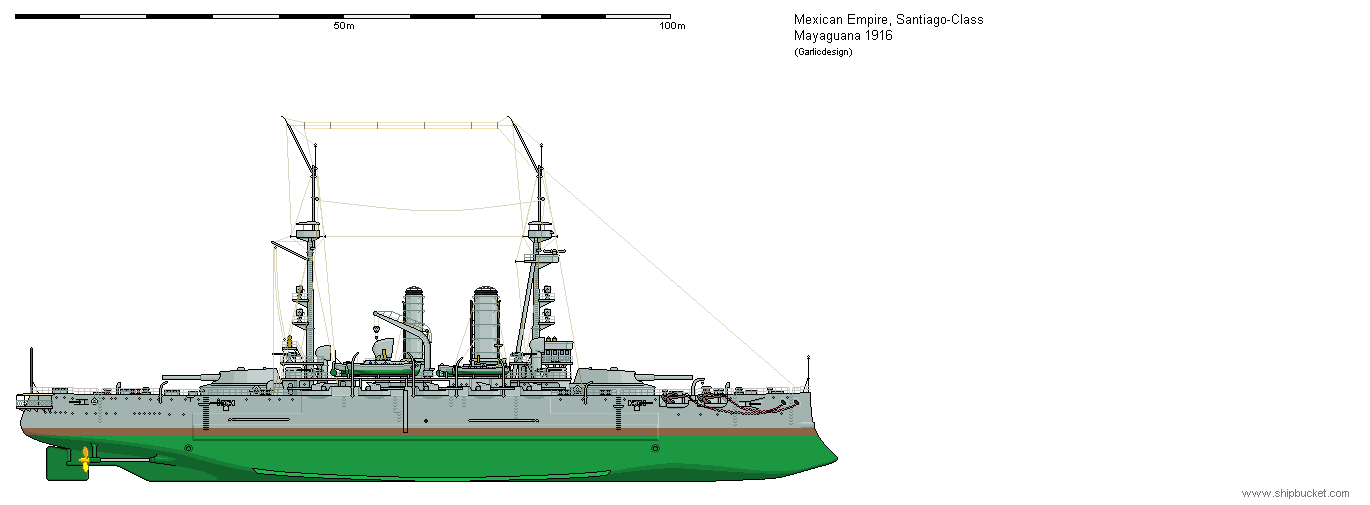

Prior to 1890, the US reaction to Mexican fleet buildup efforts had been lukewarm at best; a nation that could be overrun on land at will was not considered a long-term threat at sea. After 1890, international developments, particularly Britain’s and Japan’s (and later, also Germany’s) fleet buildup, prompted a more energetic US response, which the Mexican Empire perceived as an immediate threat to itself. The order of four new battleships for the USN in 1891 through 1893, all larger than 10.000 tons, heavily protected and armed to the teeth, was bound to provoke an Imperial reaction. Late in 1892, the Mexican Congress voted for the so-called fleet modernization act. The act called for four battleships (two of them coastal), two armored and six protected cruisers (two of them scouts), eight destroyers and sixteen torpedo boats, all of them to be made available within five years. Remarkably, the program was completed, although it would take ten years till all ships were delivered. The invitation for tender for the two big battleships went out in 1893 to a dozen yards, most of them British; the Emperor would have preferred Austrian or German, but Admiral Beltran did not trust either of these nations’ ability to deliver high-end technology. Armstrong, which was at the same time negotiating with the Japanese, finally made the offer that could not be rejected: When both orders were pooled, a homogenous class of four battleships could be built at minimal cost in minimal time. Armstrong would build two hulls themselves and subcontract one to Fairfield and one to Thames Iron Works, two each to be delivered 1897 and 1898. Late in 1893, the so far largest warship export contract in British history was finalized. Mexico would receive one of the Armstrong-built ships and the Fairfield-built one. Both were mostly identical, except Fairfield’s ship had sixteen Belleville water tube boilers and two identical flat oval funnels, while Armstrong’s ship had an oval funnel forward and a circular funnel aft and only 14 cylindrical boilers. There also were some minor differences in ventilators, shape of the ram, and secondary armament distribution. The Mexican ships had British main guns, but German and Austrian secondaries and tertiaries in order to retain commonality with Mexican standard ordnance. They were originally to be named Soberano (Sovereign) and Monarca (Monarch), but re-named in 1898 before delivery after recent victories in the Second Spanish war, becoming Mayaguana and Santiago, respectively.

Displacement:

12.320 ts mean, 13.860 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 125,60m, Beam 22,40m, Draught 7,15m mean, 8,00m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Triple Expansion, 14 cylindrical boilers (Santiago 16 Belleville Watertube boilers), 14.000 ihp

Performance:

Speed 18,0 kts maximum, range 4.000 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Harvey. Belt 457mm; Ship ends unprotected; upper belt and casemates 152mm; barbettes 356mm; Turrets 152mm front, 102mm sides; deck 63mm maximum, CT 356mm all-round

Armament:

2x2 305mm/40 Armstrong BL, 10x1 150mm/35 Krupp BL, 20x1 47mm/44 Skoda QF, 4x1 47mm/33 Hotchkiss revolver, 5x 450mm Torpedo tube (1 forward above water, 2 on each beam submerged)

Crew

740

Both ships were delivered about a year behind schedule. The Japanese order was processed in time, indicating political pressure on the building yards to prioritize. Soberano was complete in the spring of 1898, but held back in Elswick when the Second Spanish war erupted; Monarca was not completed until late 1899. Both were renamed a week after the war was ended; Mayaguana (ex-Soberano) was delivered immediately after the ceremony, reaching Mexico in November 1898.

Santiago (ex-Monarca) reached Mexico early in 1900.

Both vessels made up the first division of the Mexican battle fleet; Mayaguana was fitted as fleet flagship, relieving Poder. Like most Mexican ships, they were repeatedly called upon to assert Mexican interest in various Central American countries against US intervention; they met overwhelmingly superior US opposition in every case, and Mexico came out second in virtually every confrontation. During the second Venezuelan crisis of 1907, both ships sunk the small Portuguese battleship Corte Real. Mayaguana was relieved as fleet flagship in 1911 by the new, domestically built Victoria. When the Mexicans introduced w/t communication after 1909, both units were late to receive it, in 1912 and 1913, respectively; they also landed their fighting tops, eliminating the four Hotchkiss revolver guns, and their torpedo net defense. From 1913, when the first Dreadnought division was available, Mayaguana and Santiago formed the core of the Mexican Pacific fleet.

In 1915, Mayaguana was taken in hand for thorough modernization. The fighting tops were removed, and a spotting top and a director tower were fitted to the main mast, which had to be braced with a tripod for stability. Searchlights were re-arranged, and the bridge was enlarged. The secondary guns were replaced by 150/40 Skoda QF guns with higher ROF and relocated to the upper deck, and the tertiary battery now consisted of sixteen 66/50 Skoda QF guns.

During the war against the USA in 1916, both ships were very active under the energetic command of Rear Admiral Othon Blanco. They successfully raided the Pacific locks of the Panama channel and provided fire support to Mexican ground forces fighting around the Baja California. But on September 8th, 1916, they were en route to another attack on Panama and performed at-sea coaling off Cabo Corrientes in the Bay of Banderas, when they were engaged by the US battlecruisers Enterprise and Independence in what was to become the Battle of Corrientes. Although Mayaguana’s gunnery was excellent and scored five hits on Enterprise, Santiago blew up mere minutes into the engagement after a catastrophic hit to her Magazines, and Mayaguana, now outgunned 4:1, was reduced to a blazing inferno, sinking with most of her crew.

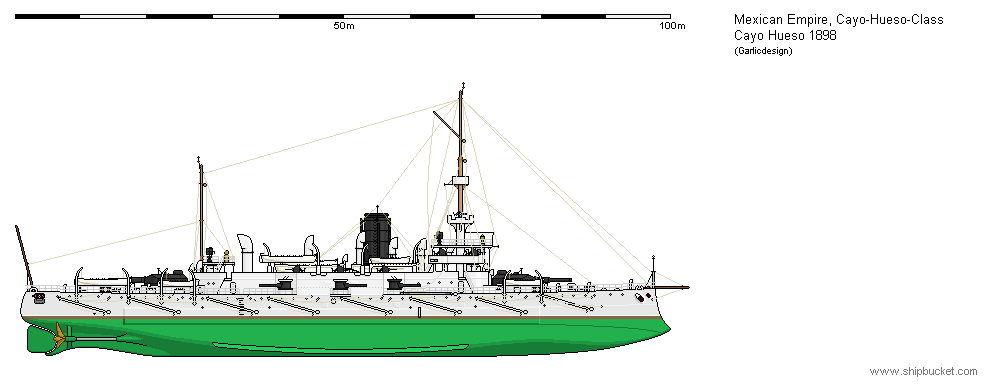

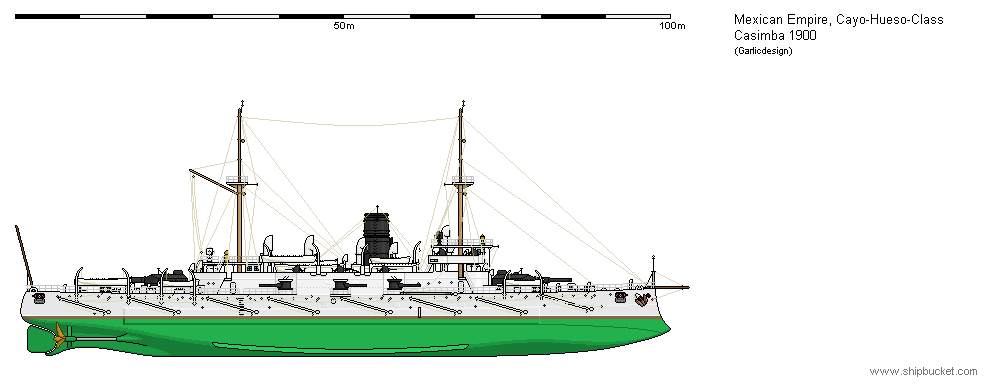

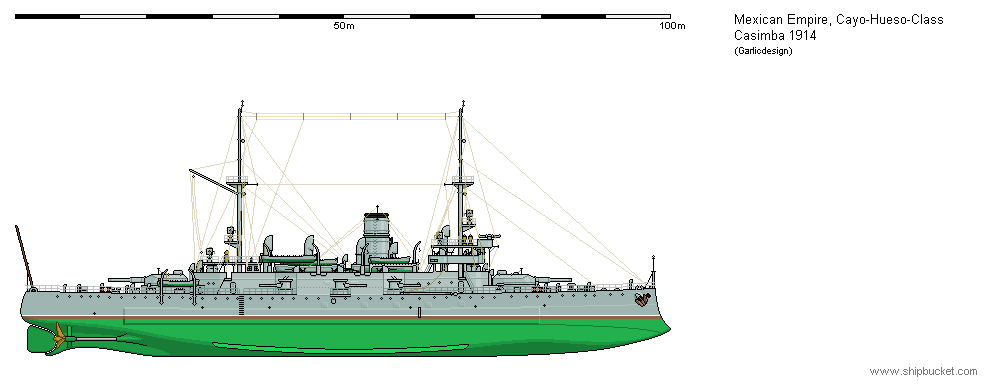

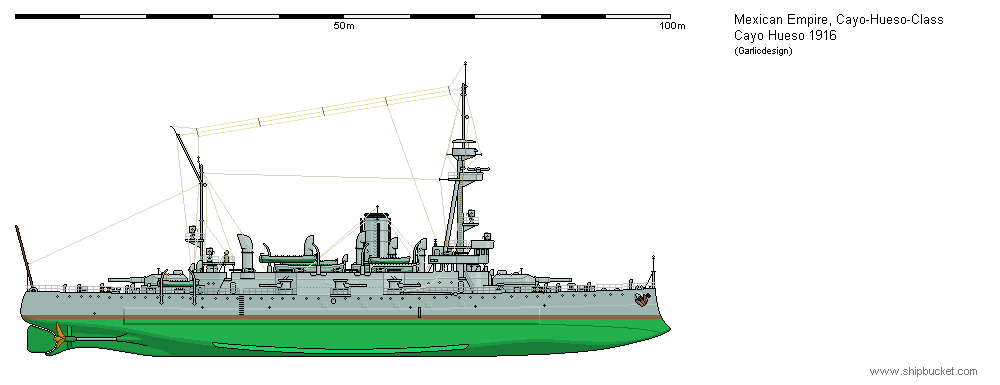

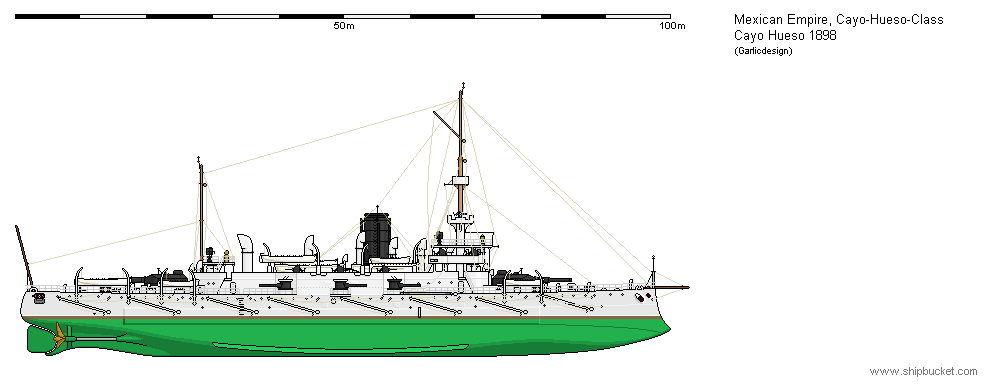

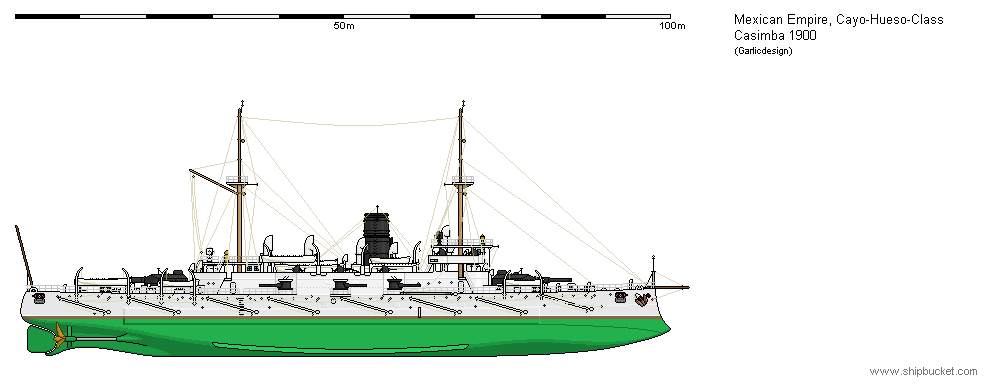

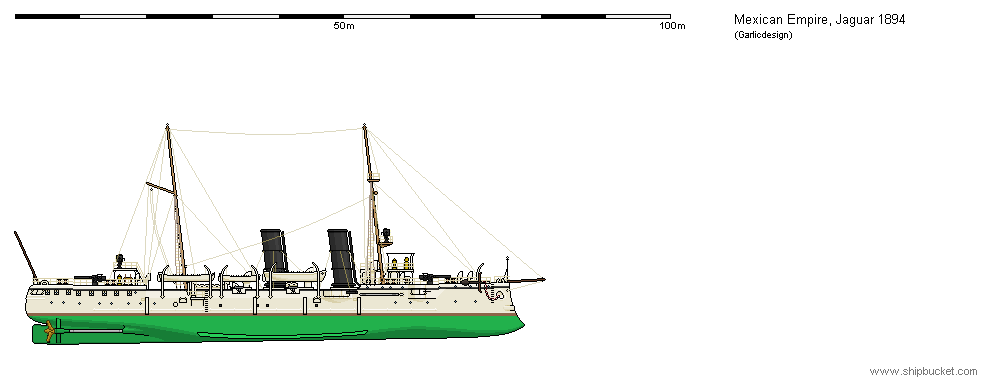

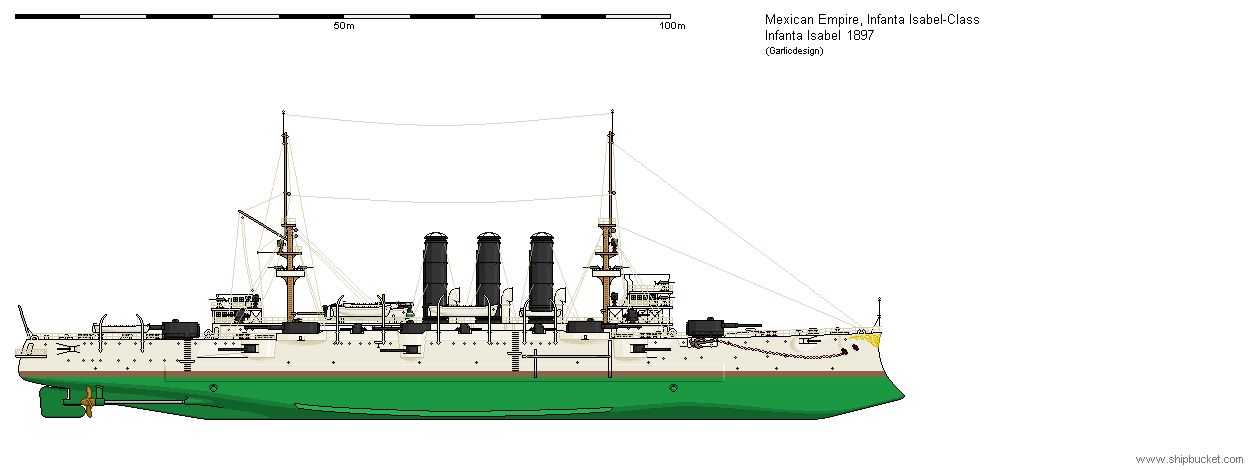

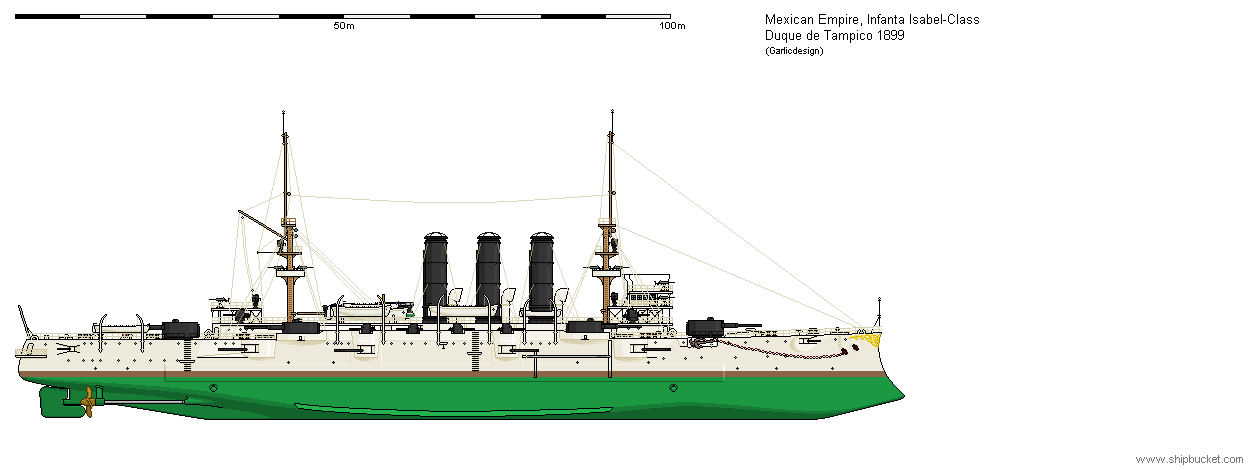

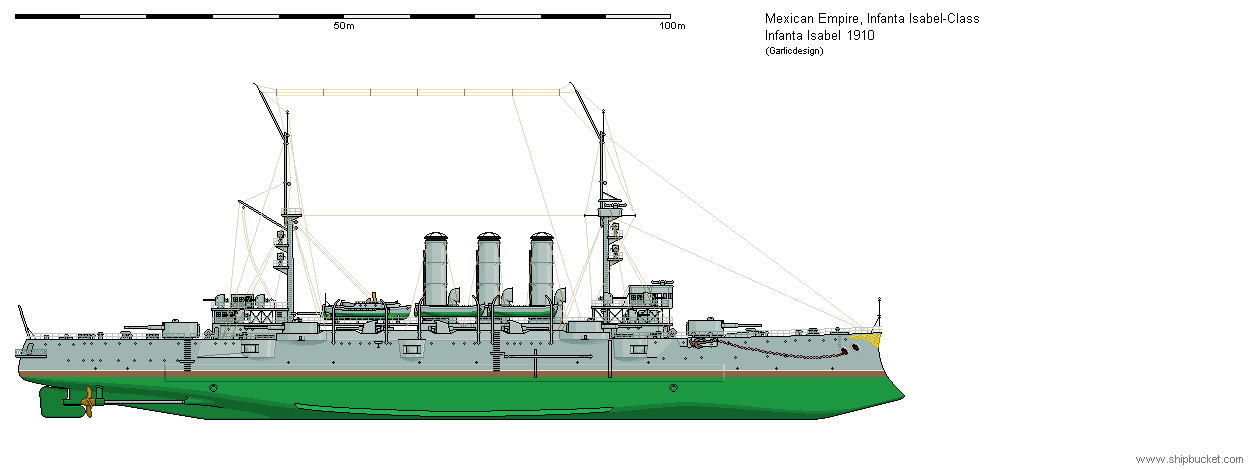

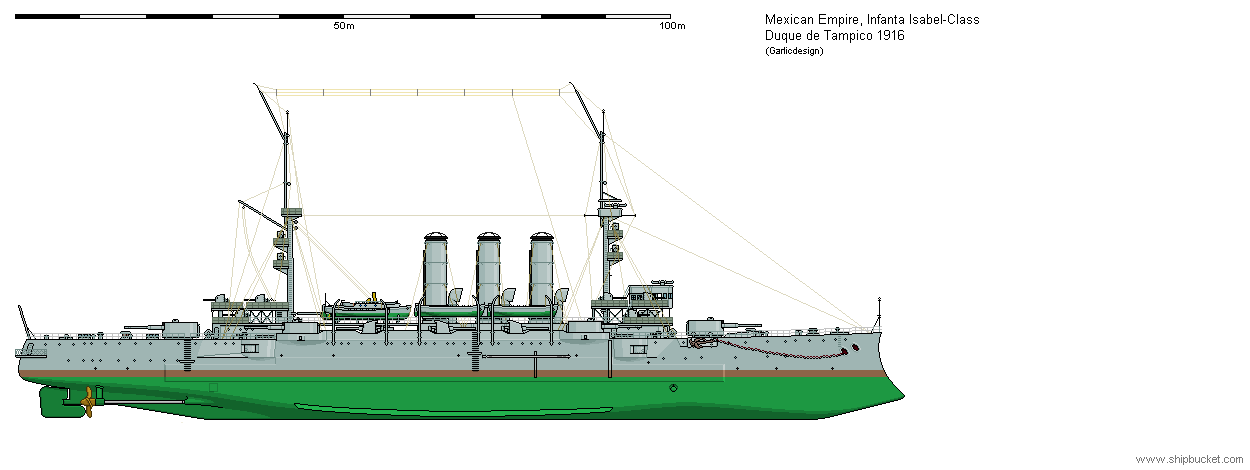

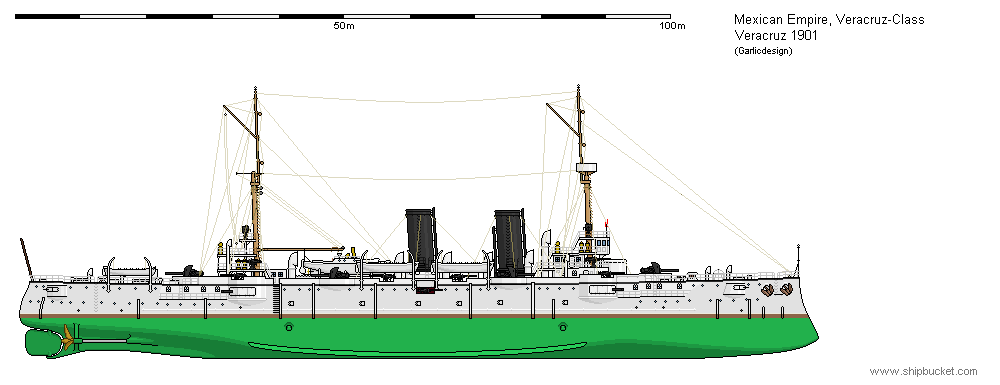

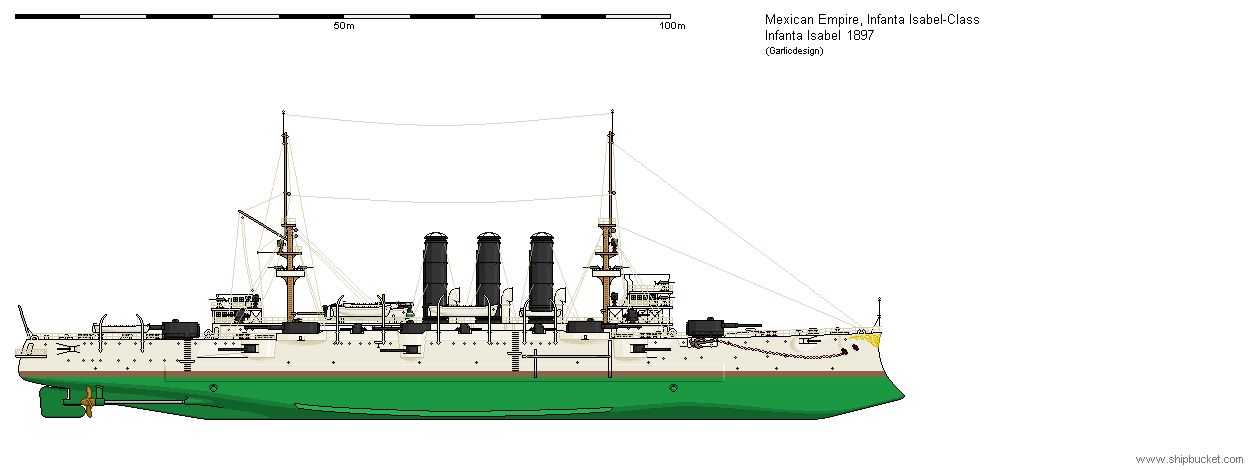

3. Cayo-Hueso-Class

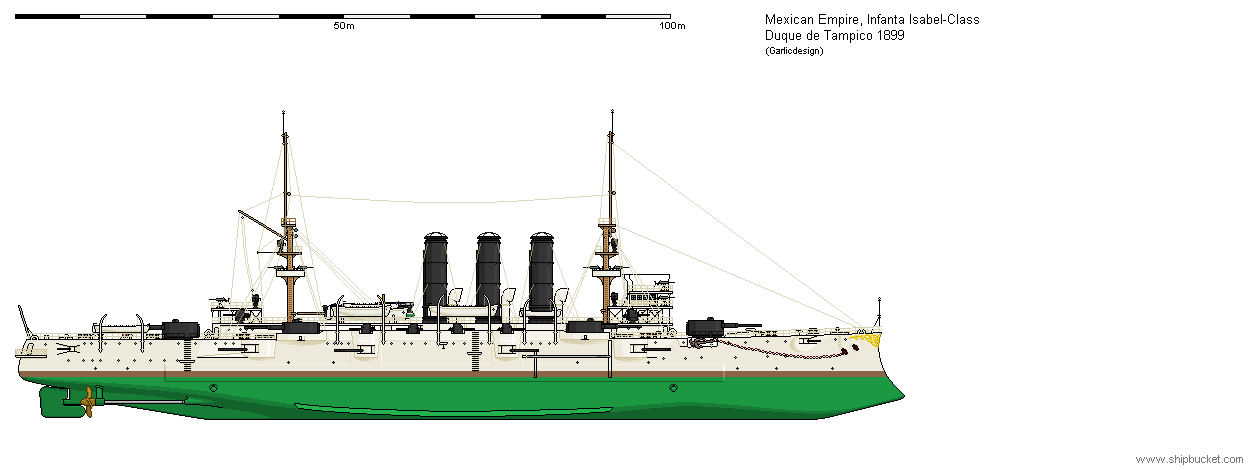

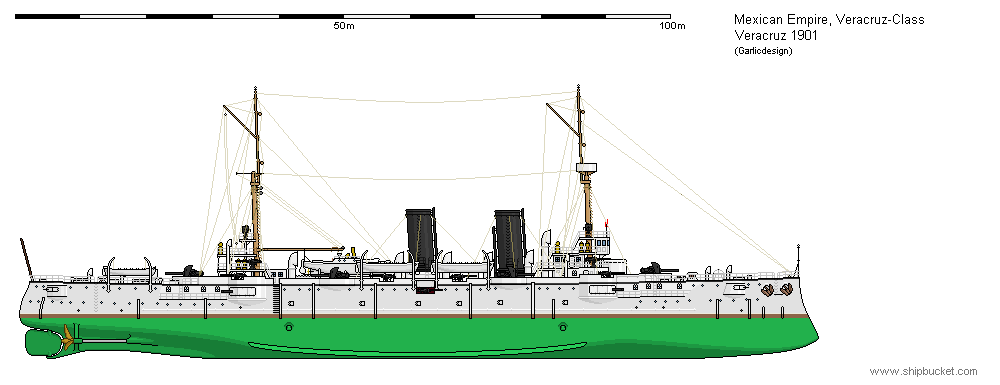

With this class, part of the big 1892 fleet modernization act, the Empire started domestic battleship construction. The contract with the STT yard at Trieste, finalized in mid-1893, included construction of one coastal battleship identical with the contemporary Monarch-class for the KuK navy, and delivery of all plans for a sister ship to be constructed at the Tampico Naval Yard. Ironically, construction of the Mexican-built ship commenced first, because STT did not have an empty slipway available before August 1895; the Tampico-built ship was laid down in May 1894. They were named after recent military successes against Spain and the USA, respectively: the battle of Casimba in 1885 and the engagement (battle would probably be an exaggeration) off Key West (Spanish: Cayo Hueso) in 1890.

Displacement:

5.640 ts mean, 6.170 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 99,20m, Beam 17,00m, Draught 5,80m mean, 6,40m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Triple Expansion, 7 cylindrical boilers, 8.500 ihp

Performance:

Speed 17,5 kts maximum, range 3.000 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Nickel steel. Belt 270mm; Ship ends 220mm; Turrets 250mm max; casemates 80mm; deck 40mm maximum, CT 250mm all-round

Armament:

2x2 240mm/40 Krupp BL, 6x1 150mm/35 Krupp BL, 10x1 47mm/44 Skoda QF, 4x1 47mm/33 Hotchkiss revolver, 2x 450mm Torpedo tube (beam, above water)

Crew

426

Although construction of Cayo Hueso had commenced nearly a year later, she was built by an experienced shipyard and delivered on schedule after 36 months in September 1898, barely missing the Second Spanish war of 1898. She was identical in every respect to the Austrian Monarch-class, with a military mast forward and a short pole mast aft.

Casimba needed nearly twice the gestation period and was not delivered before March 1900, owing to unexperienced shipyard personnel and delays in delivery of her german-made gunnery because of the Second Spanish war. She differed from her sister by having two identical pole masts fore and aft; one pair of 47mm revolver guns, which was mounted atop the military mast on Cayo Hueso, was installed in a bow casemate.

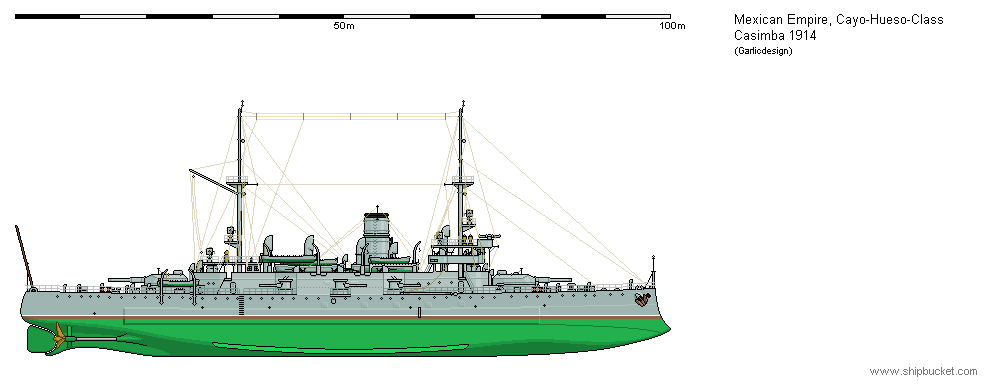

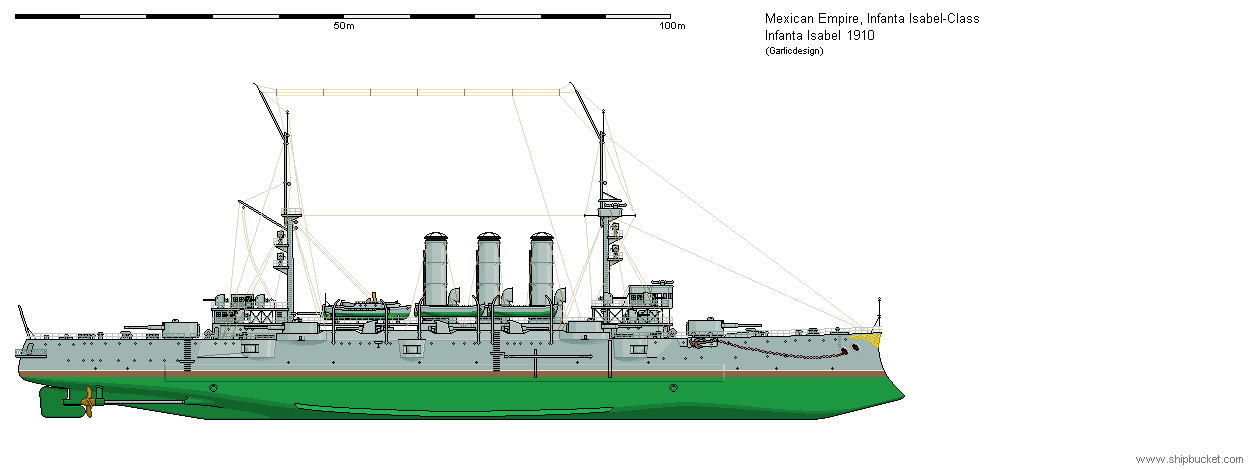

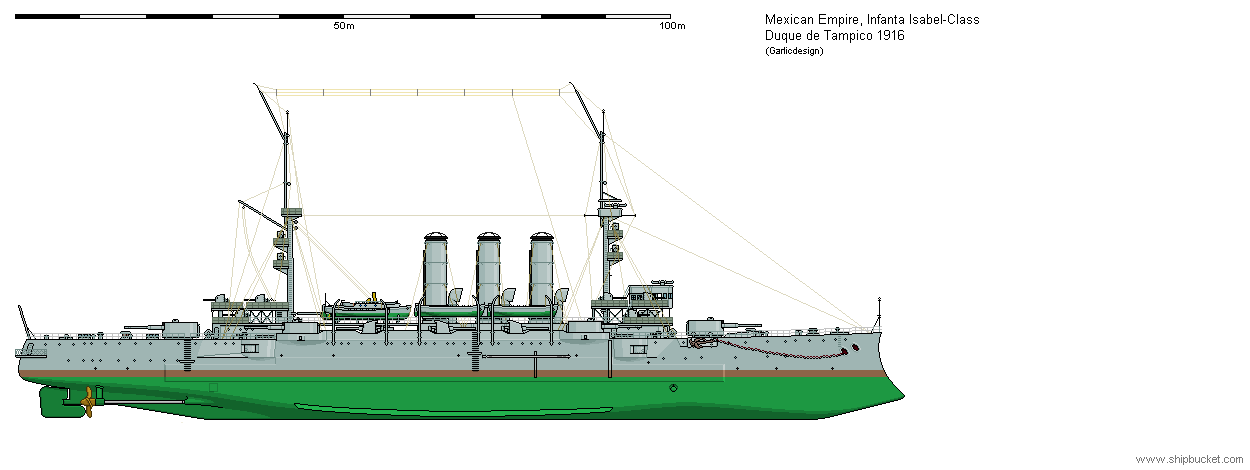

From 1901, this pair of battleships formed the mainstay of the Mexican Pacific Fleet, until the arrival of the first dreadnoughts in 1912. Whereas the Mexican main fleet was involved in numerous face-offs with the increasingly assertive USN during the 1900s, Casimba and Cayo Hueso had a relatively quiet life, resulting in a reputation of poor discipline among their crews. In 1913, they returned to the Caribbean and were taken in hand for an overhaul at Veracruz (Casimba) and Tampico (Cayo Hueso). Casimba received a modernized bridge with up-to-date fire control arrangements including rangefinders and more searchlights, and a w/t rig. Less visible was an increase in main battery elevation, oil spray gear to her boilers and sprinkler equipment for her magazines. She also landed her useless torpedo net.

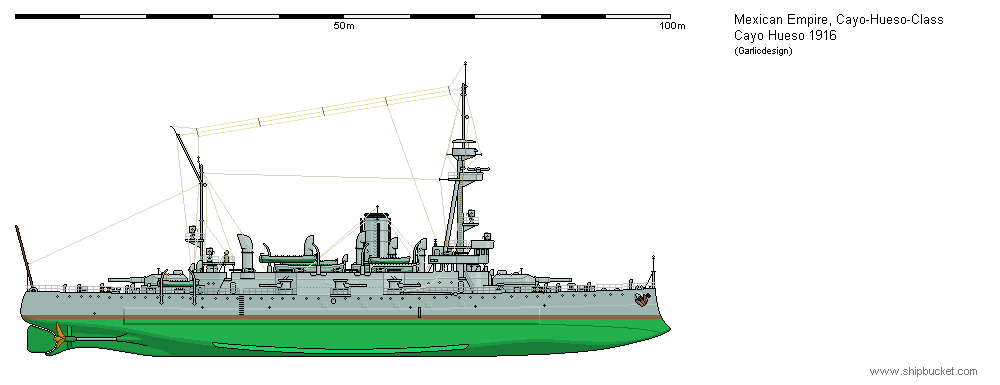

Cayo Hueso’s refit was more comprehensive. In addition to the measures taken on Casimba, she received a more extensive bridge reconstruction, had a tripod mast with experimental director fire control gear installed, and was completely reboilered with 12 small-tube boilers of domestic production.

Despite such modernization, both ships remained in reserve afterwards because of crew shortages in the wake of Admiral Beltran’s naval expansion program. When Mexico and the USA went to war in 1916, both were used as guard ships with reduced crews at Tampico (Cayo Hueso) and Veracruz (Casimba), respectively. Cayo Hueso played an active part in Tampico’s defense against US ground forces, providing precise counterbattery fire which did a lot of hurt to US Army artillery units involved in the siege. She was eventually removed from the equation when three US pre-dreadnoughts started to bombard Tampico from the sea; Cayo Hueso was hit a dozen times by USS Maine and Ohio, sinking in shallow water. She was salvaged in 1922 and scrapped. Casimba survived the war and became an American prize; she was sunk as a target in 1923.

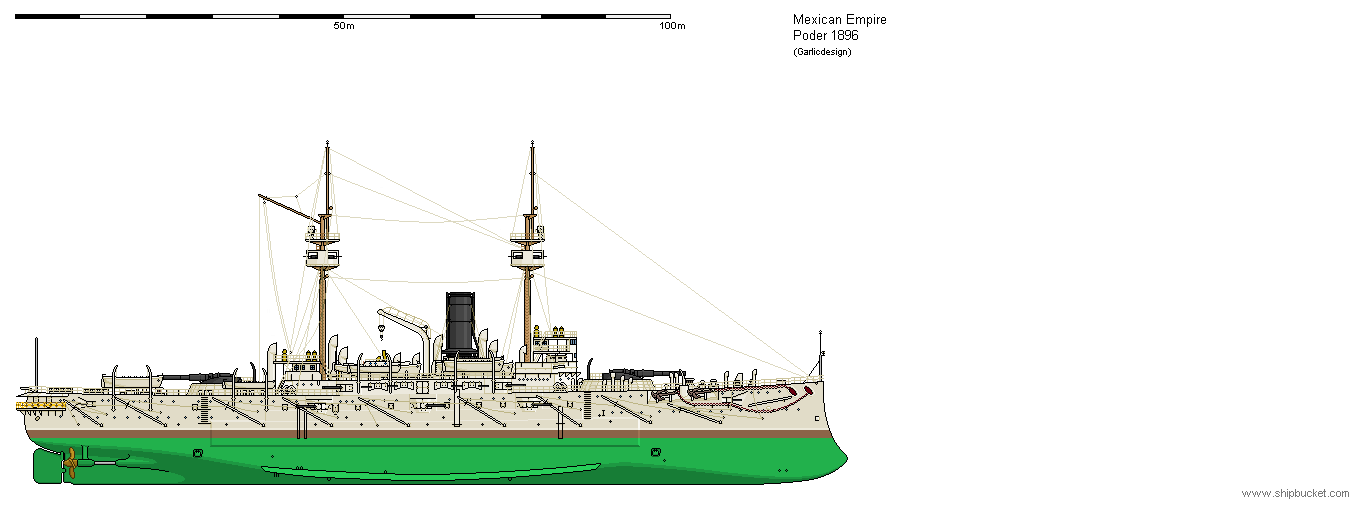

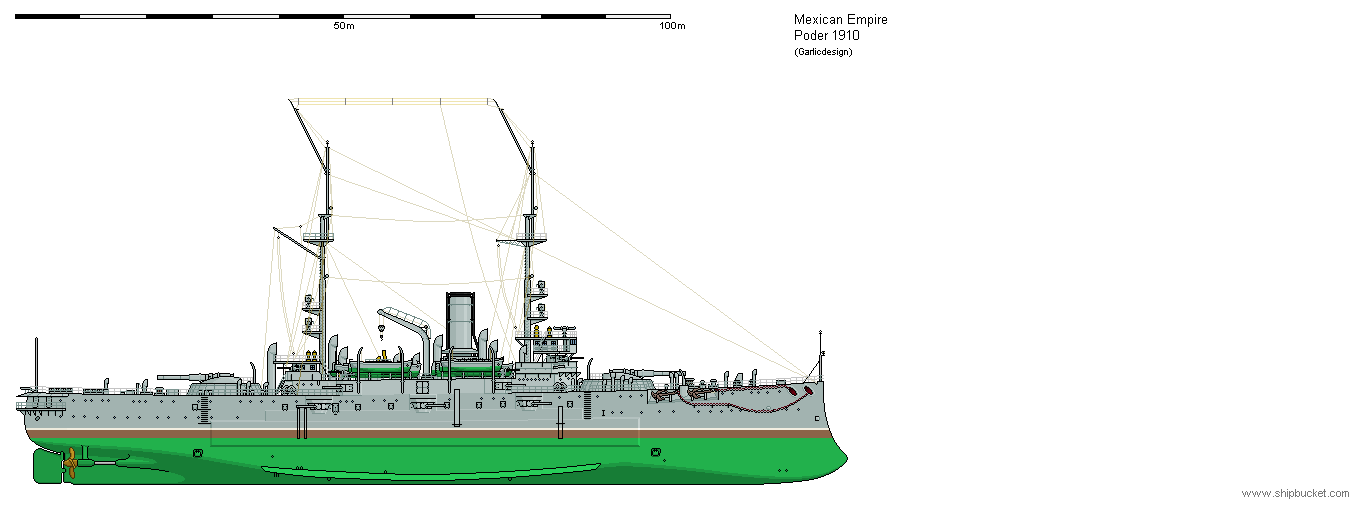

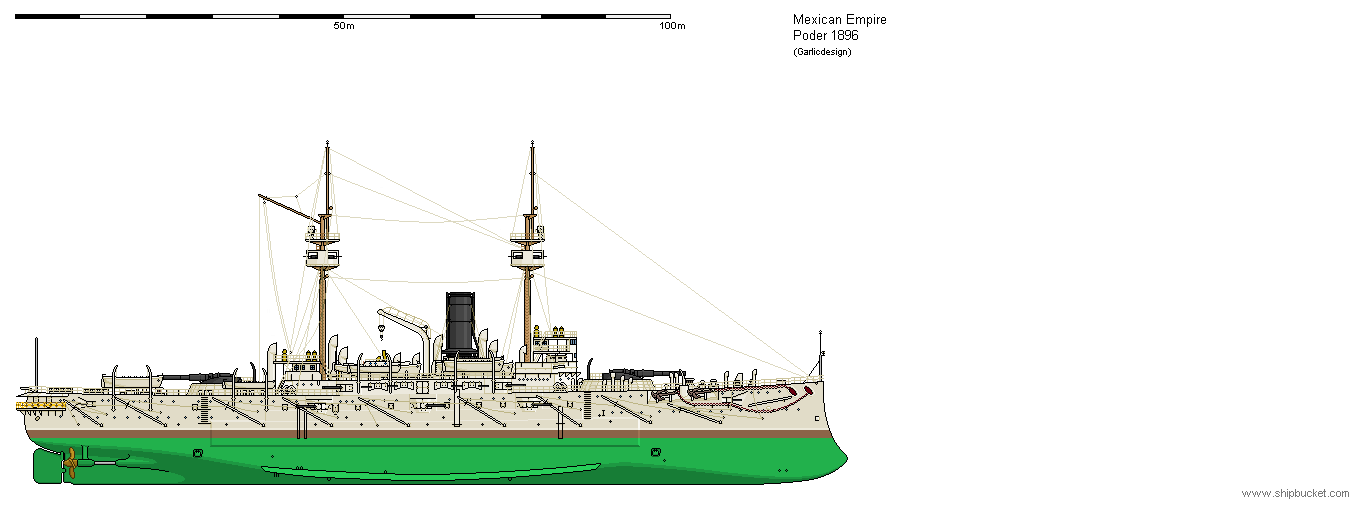

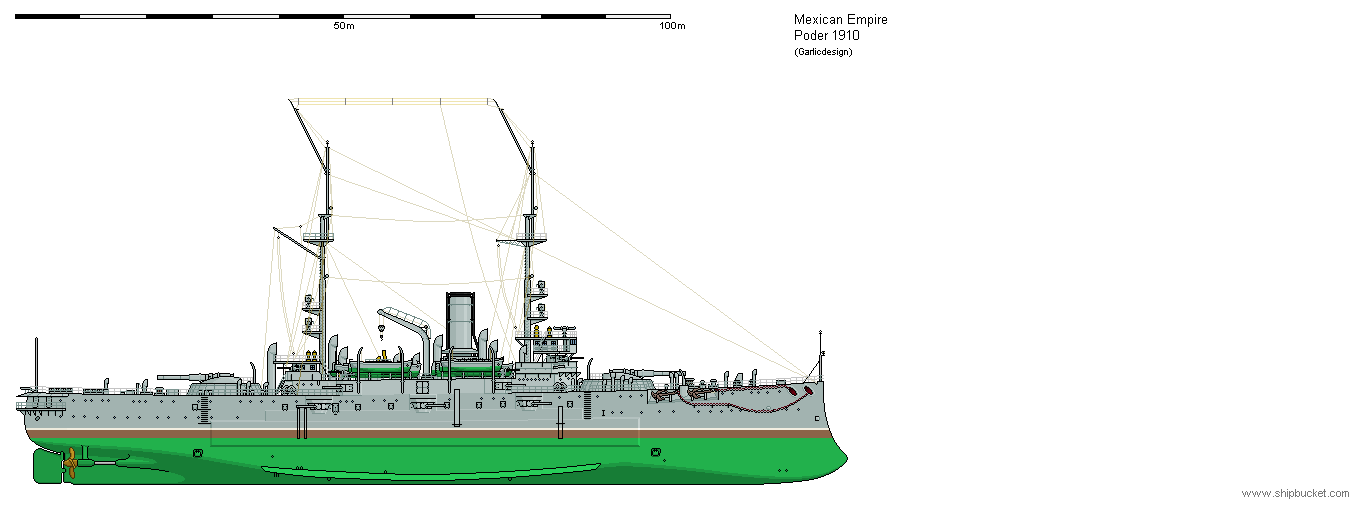

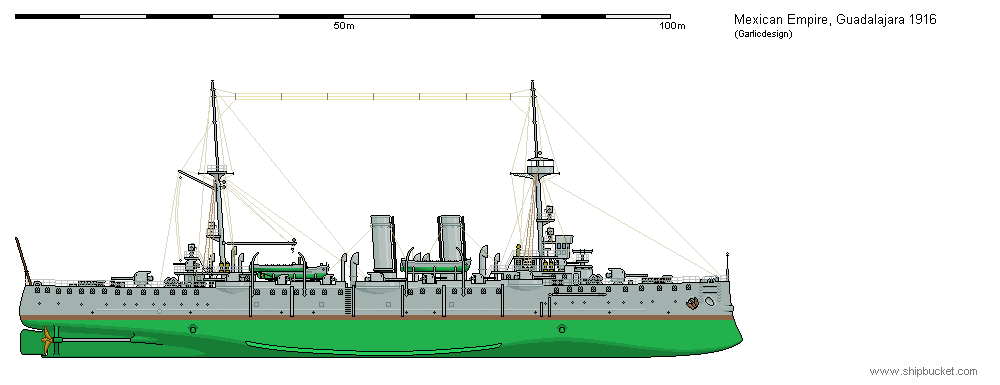

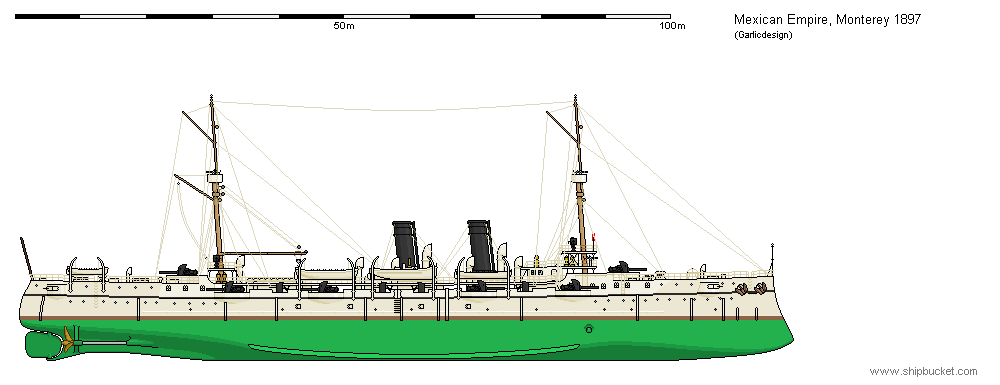

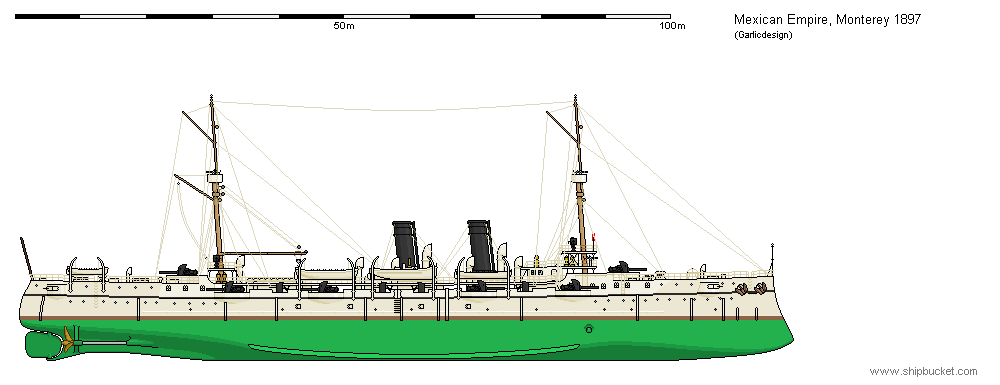

4. Poder

The order of two big battleships for the Japanese Navy in Great Britain in 1893 prompted the Chinese Empire to follow suit with a British-built battleship of their own that same year. They chose the basic design of Britain’s own HMS Renown, then the most modern, but insisted on 305mm guns; as the installation of 305mm twin turrets was hardly feasible on the same displacement, they settled for mounting them in open barbettes. Renown was dockyard-built; the Chinese placed the order for their clone at Thames Iron works. She had just been laid down when China suffered a crushing defeat against the Japanese. Payments continued to flow through 1895, then dried up just after launch as the Chinese struggled with the financial consequences of their defeat. The well-advanced hull was offered for sale to a third party by the yard in November 1895, and in January 1896, the Mexicans – anxious to acquire more battleships after the USA had recently ordered five new ones in short succession – eagerly stepped in and purchased the ship. Construction then went ahead swiftly, and the ship was delivered in November, 1897, after being fitted with German guns (which also had been part of the original Chinese order). Her name means ‘power’ in Spanish.

Displacement:

12.600 ts mean, 14.750 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 126,80m, Beam 22,00m, Draught 7,15m mean, 8,15m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Triple Expansion, 8 cylindrical boilers, 12.000 ihp

Performance:

Speed 18,5 kts maximum, range 3.000 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Harvey. Belt 203mm; Ship ends unprotected; Barbettes 254mm; upper belt and battery 152mm; deck 76mm maximum, CT 229mm all-round

Armament:

2x2 305mm/35 Krupp BL, 10x1 150mm/35 Krupp BL, 12x1 66mm/40 Skoda QF, 8x1 47mm/33 Hotchkiss revolver, 5x 450mm Torpedo tube (1 forward above water, 2 on each beam submerged)

Crew

674

She crossed the Atlantic in mid-winter without any trouble; with her unusually high freeboard and powerful machinery, Poder was among the fastest and most seaworthy battleships worldwide. She also was – for the time being – the biggest warship in Mexico’s inventory, also considerably bigger (but poorer armed and protected) than any US battleship. She was just worked up when Admiral Pacheco flew his flag from her in the Second Spanish war; she formed the first division with San Juan de Ulua. Her guns sank the Spanish battleship Isabel la Catolica during the Battle of Mayaguana and damaged the battleship Pelayo during the second battle of Santiago; she took scant damage herself (which was fortunate, because she was not very good at withstanding damage).

After the Second Spanish war, she remained fleet flagship till delivery of the new pre-dreadnoughts Santiago and Mayaguana; she and San Juan de Ulua now formed the second division. During the 1900s, she had several run-ins with US naval forces when the latter imposed US dominance on various smaller Latin American nations; as the Americans usually were numerically superior and determined to shoot at the slightest provocation, all of these encounters ended in humiliating retreats for the Imperial fleet. During the second Venezuelan crisis, Poder was dispatched as reinforcement, but failed to join up with the fleet before the crisis was resolved. Poder was modernized in 1910, landing her torpedo nets and her 47mm tertiary battery; the secondary battery was reduced to eight 66mm Skoda guns, but of a newer 50-caliber model. She received new and re-arranged searchlights, up-to-date fire control gear and a w/t-rig, being the first Mexican capital ship to be so fitted.

She remained with the main battle fleet till 1913, when she blew up off Veracruz due to decaying gun propellant charges. Many of her crew survived because they were on shore leave; 431 died.

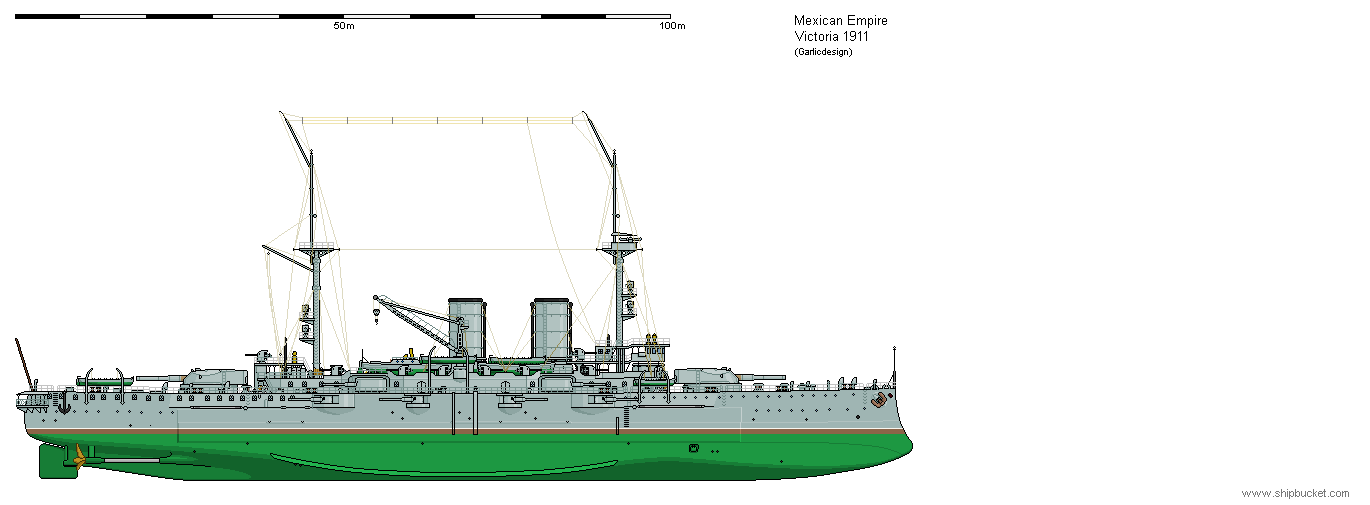

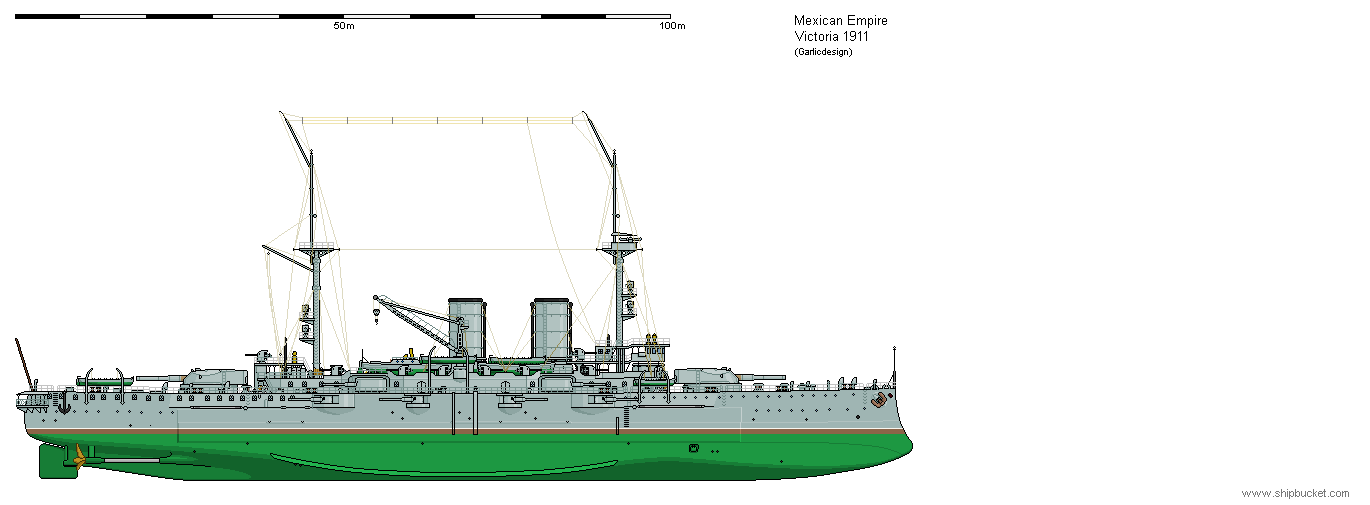

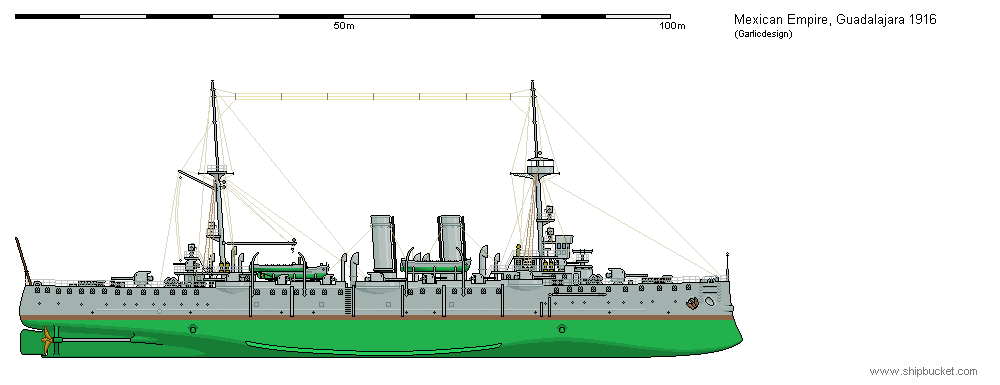

5. Victoria

After Mexican industry had successfully delivered a coastal battleship in 1900, the natural next step was an oceangoing one. The project unfortunately was pursued at a time of tight funding after the Second Spanish War, when the army was prioritized under General Huerta’s influence, while the Emperor’s health and authority were failing. Several designs were drawn up and rejected between 1899 and 1901, and Congress even officially cancelled the project early in 1902, just when Mexican Naval designers and Austrian civilian designers of the STT yard had come up with a practicable design. The reasoning was that the US had commissioned 16 battleships during the last ten years and any attempt to keep up with them was futile. Admiral Beltran however pointed out that the increasing rate of US interventions in Central American nations was directly linked to the USN’s ever-increasing strength, and Mexico at least would need the capability to inflict some bloody losses in order to prevent becoming a victim herself; to achieve that, he wanted four new battleships. After long discussions, construction for a single ship was approved in 1903, to be built at the Tampico Naval Yard. The design outwardly resembled a twin-funnel variant of the contemporary Austrian Erzherzog-Karl-type, but was half again as big and had 305mm main guns and considerably stronger protection. At that time, the dreadnought era was already imminent, but Beltran pushed the project through, if only to prove that Mexico was capable of building the biggest type of warship in existence. The ship, named Victoria (Victory), was laid down early in 1904 at Tampico. The yard indeed proved able to deliver quality, but construction time exceeded projections by nearly 100%, lasting till late 1910, at a time the ship was utterly and hopelessly obsolete.

Displacement:

15.080 ts mean, 17.340 ts full load

Dimensions:

Length 136,85m, Beam 22,70m, Draught 7,15m mean, 8,20m full load

Machinery:

2-shaft Vertical Triple Expansion, 20 Belleville-type (built by construction yard) water tube boilers, 18.500 ihp

Performance:

Speed 20,0 kts maximum, range 5.500 nm at 10 knots

Armour:

Krupp. Belt 270mm; Ship ends 150mm forward, unprotected aft; upper belt and casemates 170mm; barbettes 310mm; Turrets 270mm front, 210mm sides; deck 70mm maximum, CT 310mm all-round

Armament: