Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

Moderator: Community Manager

Re: Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

Damn that is a hot fighter! A fine feast for the eyes!

Hood's Worklist

English Electric Canberra FD

Interwar RN Capital Ships

Super-Darings

Never-Were British Aircraft

English Electric Canberra FD

Interwar RN Capital Ships

Super-Darings

Never-Were British Aircraft

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

Hi all!

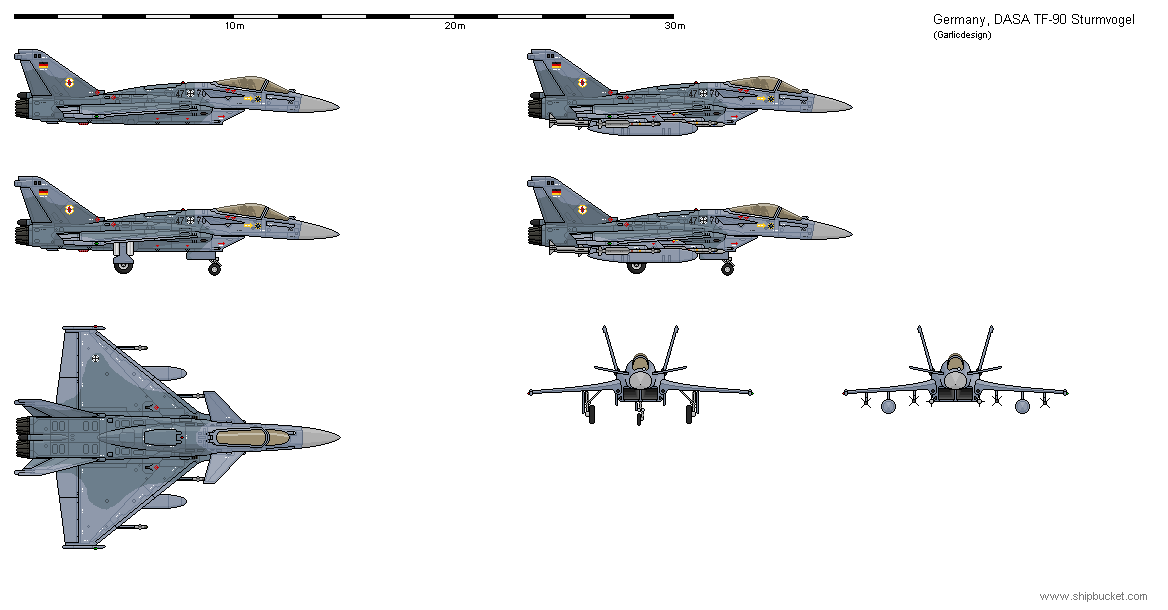

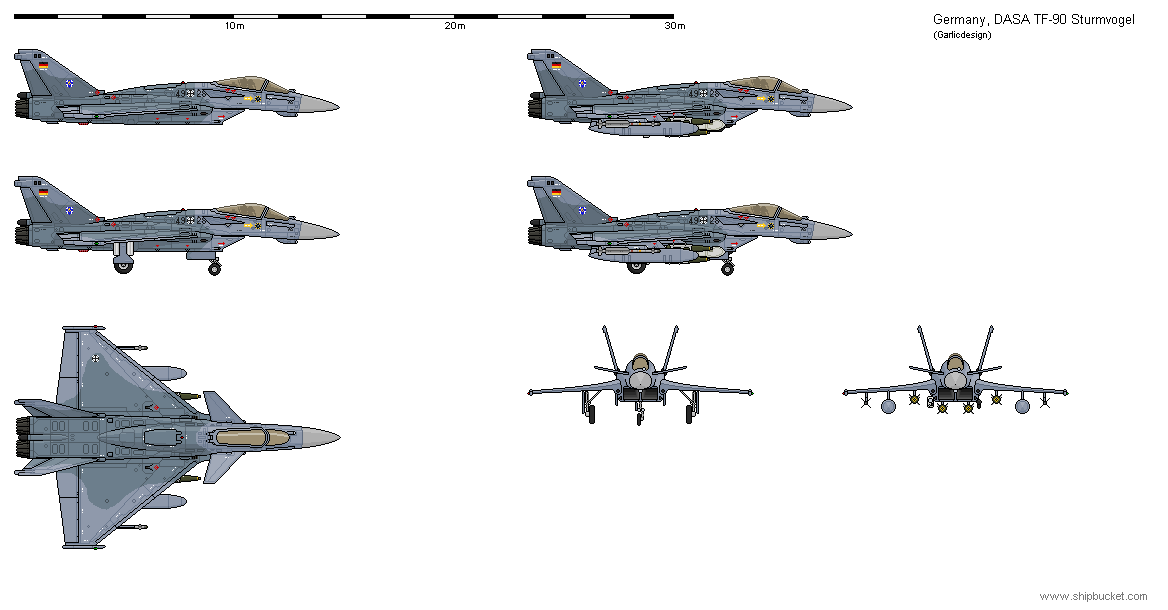

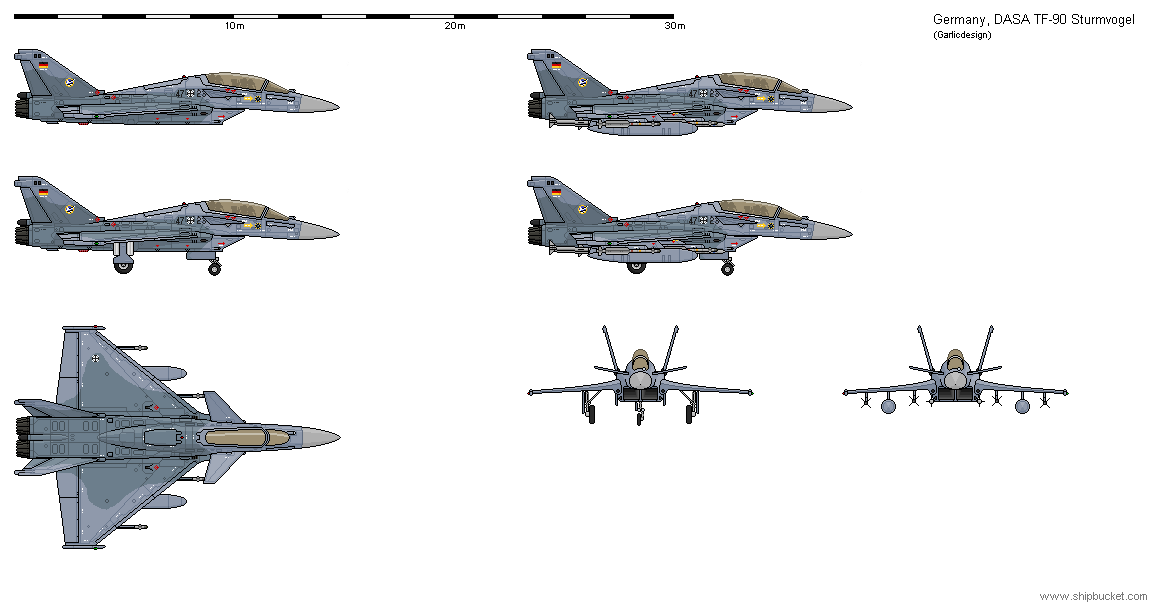

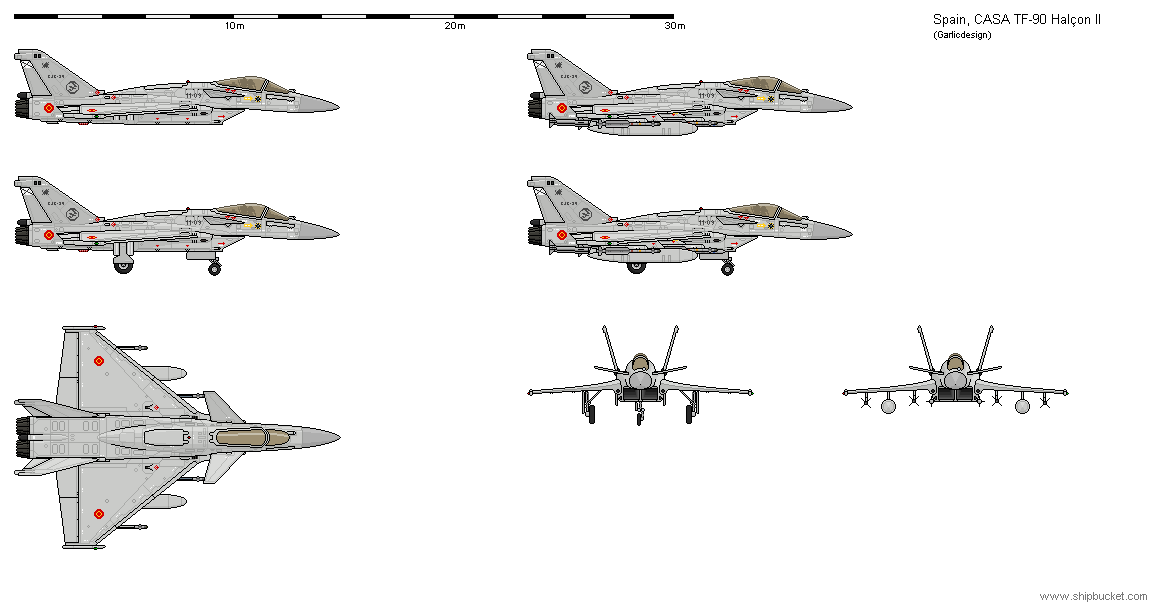

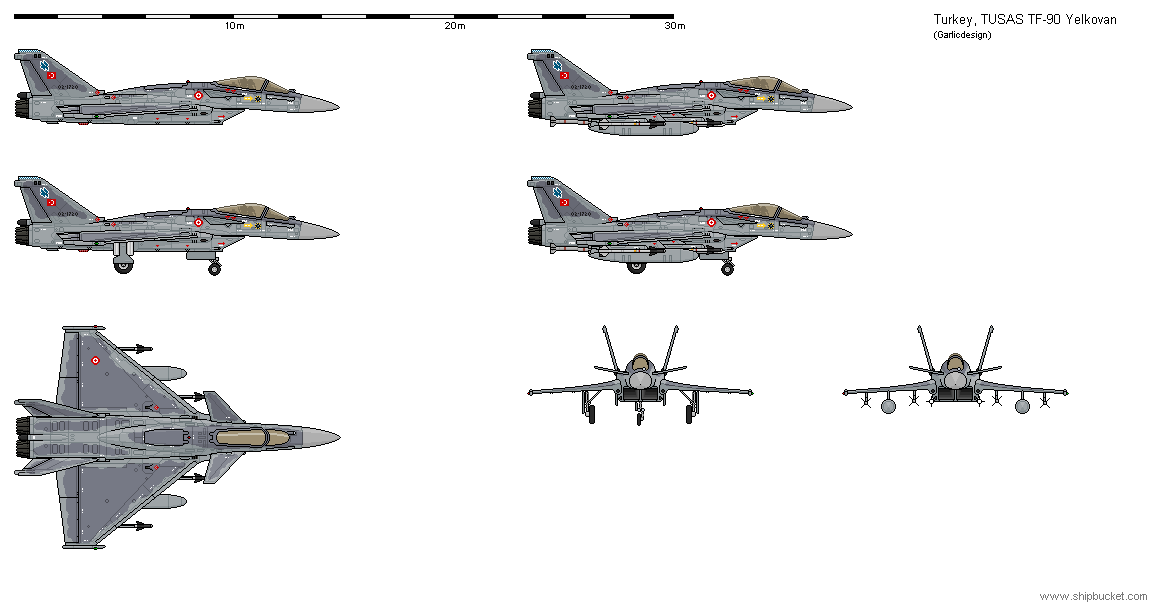

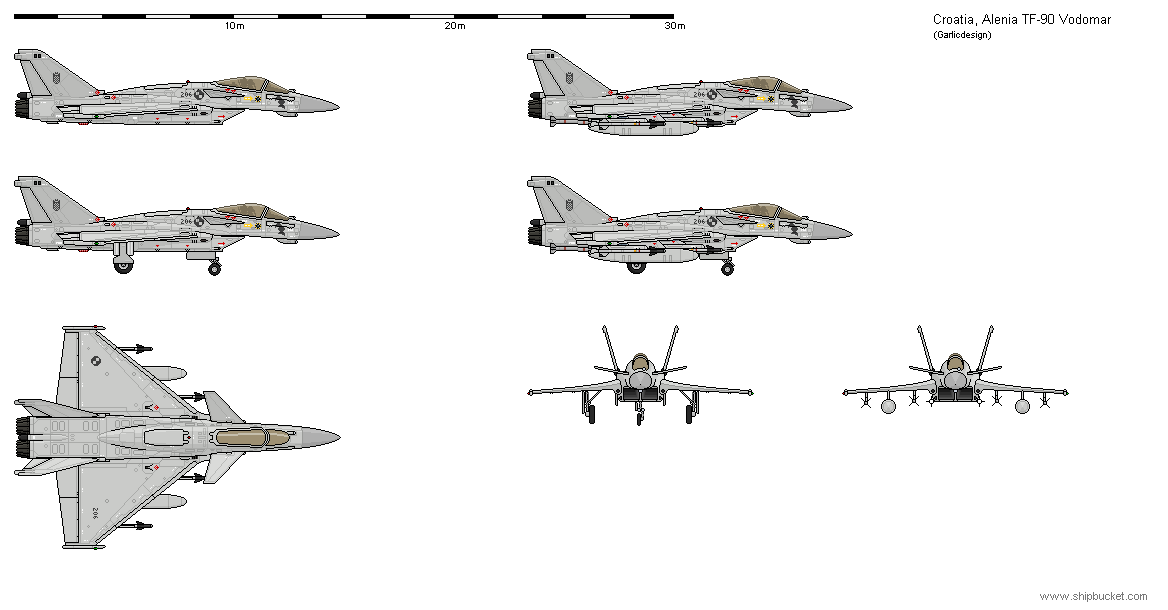

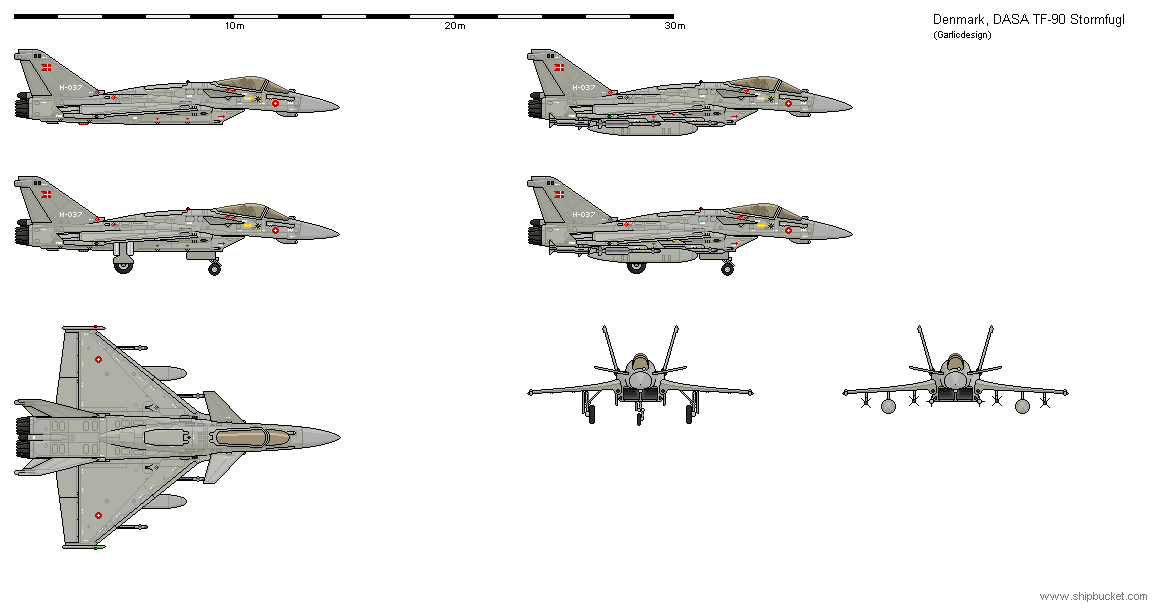

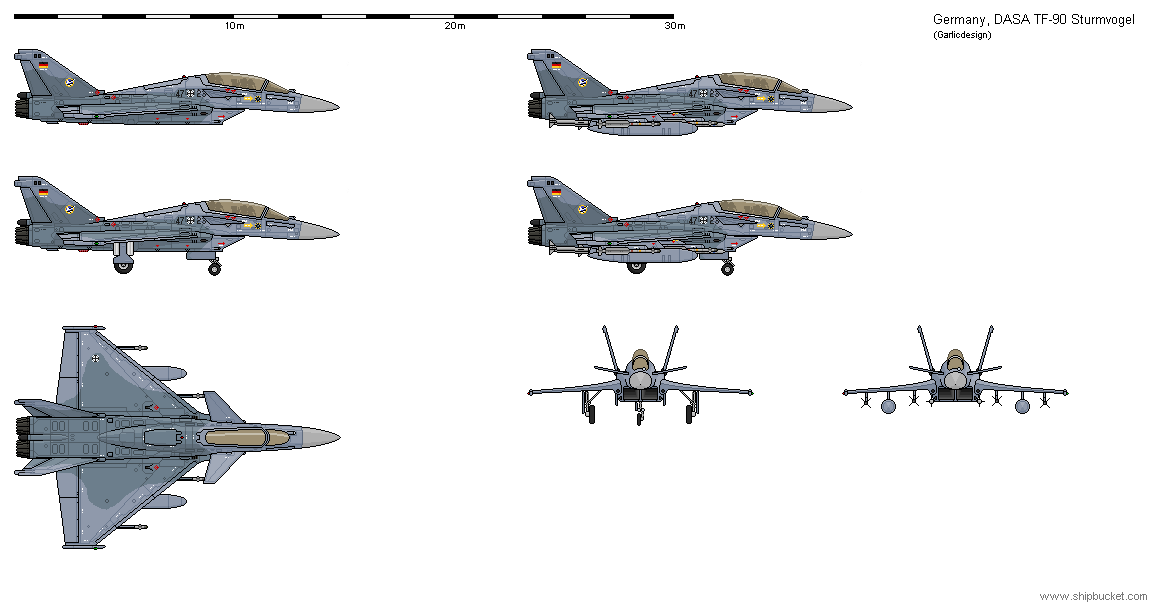

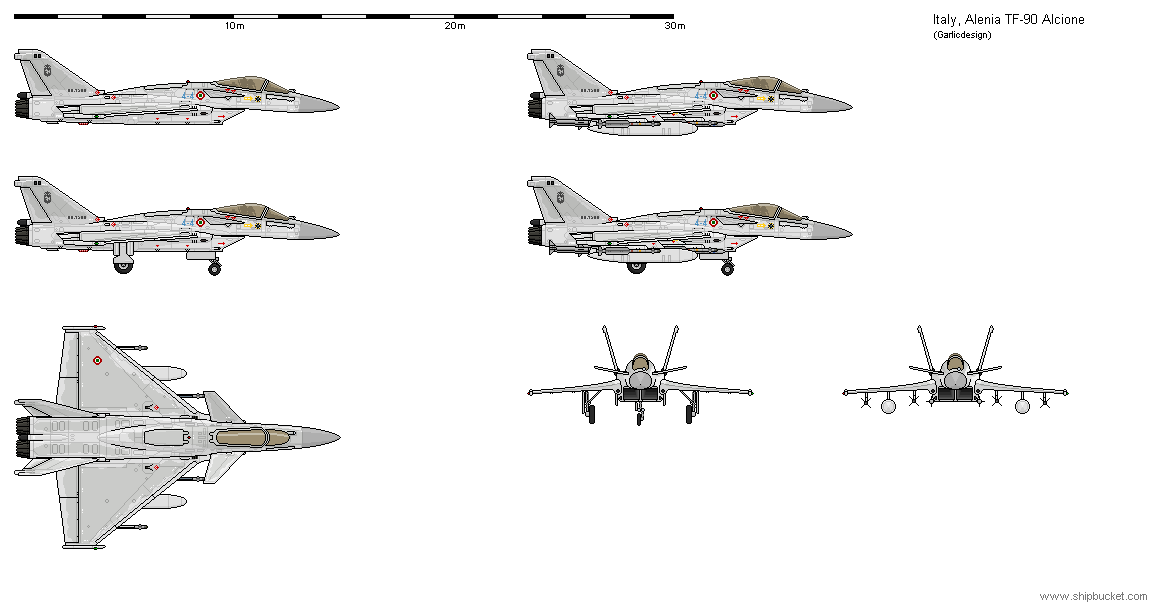

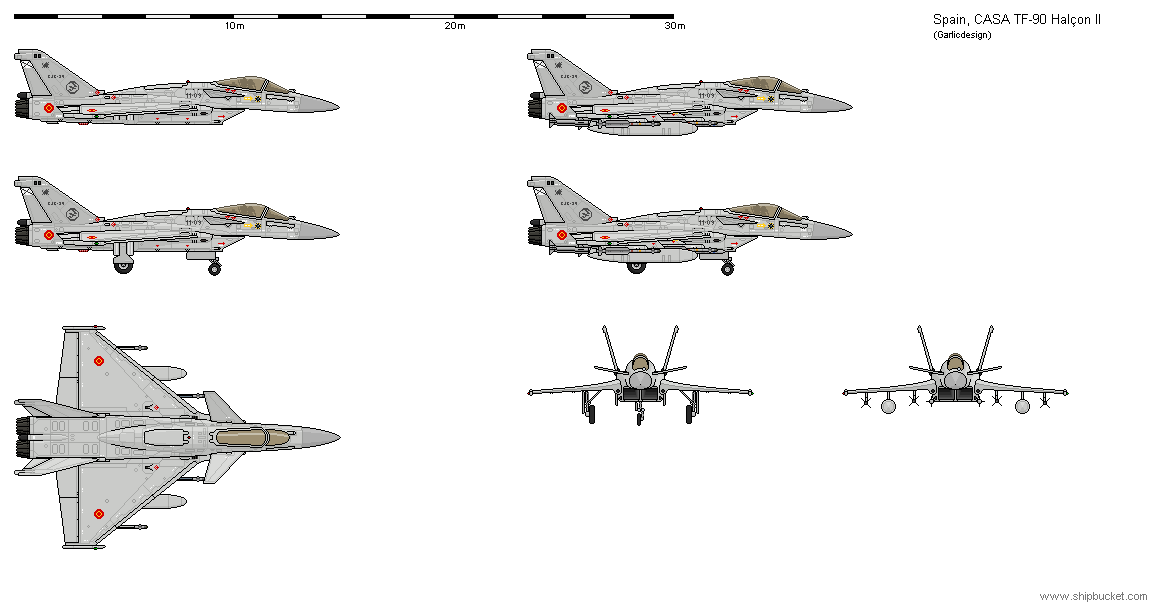

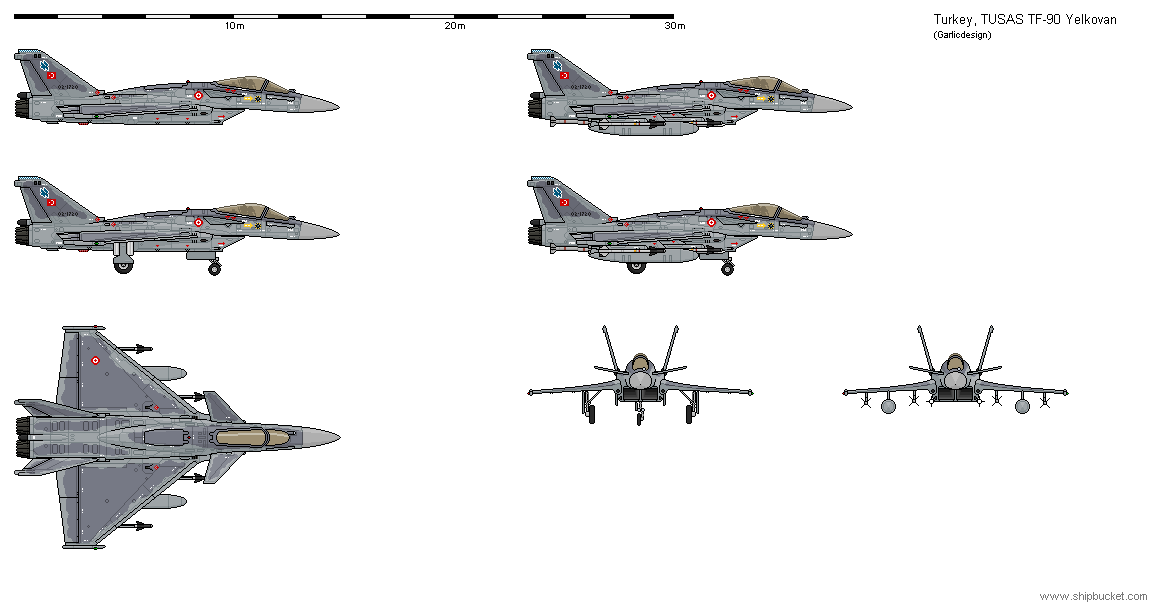

DASA/Alenia/CASA TF-90 Sturmvogel / Alcione / Halcon II

In 1983, a five-national (Great Britain, France, West Germany, Italy and Spain) project for design and production of a Generation 4.5 Fighter to equip Europe’s Air Forces in the 1990s was launched. France, Germany and Great Britain all had designs for canard twinjets of similar size, which were to be merged into a single type to satisfy a joint initial requirement for a thousand machines. Within two years, politics tore the project apart. France, Great Britain and Germany all wanted project leadership; France and Great Britain each wanted to provide the engines; and both nations wanted carrier capability, which nobody else needed. The French left the project in 1985 and proceeded to independently develop Rafale, and Margaret Thatcher killed it dead with her 1985 decision to adopt the Hale Tempest with British-built radar, avionics, weapons and RB.246 engines for both the RAF and the FAA, eliminating British requirement for another fighter for the next twenty years. The Germans, Italians and Spaniards were thus left with a German concept study (TKF-90 dating to 1979), no engine and no avionics kit. Sensible people might have called it a day, but the German government had already spent two billion marks of development expenses (half of it swallowed by the Brits and French) and decided to put TKF-90 into the air, if only to prove that they could. They were also bribed. With the requirement for carrier capability gone, the plane’s size and weight could be reduced, although the initial requirement for eight tons empty weight proved impossible to meet. The dorsal spine of TKF-90 vanished, replaced by a Flanker-ish hump with large central air brake and a bubble canopy, providing more space for fuel and electronics as well as better pilot view. Simplicity was also a factor: Fixes air intakes were fitted, limiting top speed to Mach 1,8 regardless of engine power. The originally planned thrust vector control option was dropped, as were air-to-ground capabilities, making the plane a single-role air superiority fighter. The final design retained twin horizontal stabilizers for maximum maneuverability, but moved the canards from the very bow to a position directly above the wing roots, just like Rafale and the Israeli Lavi. This allowed for better maneuverability at low altitudes and speeds, a particularly important feature for the Germans who needed to operate in an environment saturated with enemy SAMs. The prior focus on high-speed, high altitude performance had largely been a British demand (the Italians and Spaniards would still have liked it, but with German money keeping the whole project aloft, they were overruled). The somewhat more stable aerodynamic layout also allowed the plane to stay aloft if the canards were incapacitated by battle damage, which would have been questionable with the former layout. To minimize expenses, off-the shelf systems were to be used wherever possible, in a modular arrangement that would allow later upgrades. Thus, rather than developing an all-new engine, MTU acquired a license for the well-proven GE F404. The MSD-2000 radar was a much improved AESA version of the APG-65, built by Alenia, which also provided the avionics package. Armament consisted of two fixed 27mm Mauser cannon in the wing roots with 150 rpg, conformal bays for four AMRAAMs and six hard points (two of them wet) for an external weapons load of 4.000 kilograms, this low figure reflecting the plane’s single-role fighter nature.

As development work proceeded, the partner nations agreed on the scope of work share in 1987. Germany, with a requirement of 264 planes to replace the Mirage F.4 one for one after that type reached the end of its designed twenty-year service life in 1996, would lead the project and provide 48% of the parts: Engines including fuel system and aerial refueling gear, guns, running gear, all auxiliary machinery, all control surfaces and all production plant equipment. Italy’s requirement for 164 machines, replacing the Lockheed F-13 from 1995, translated into a share of 32%; the Italians would provide radar, avionics including the software package, cockpit interior including instruments and ejector seat, and most of the fuselage. Spain’s requirement for 90 machines, replacing the Mirage F.1 from 1994, gave them a 20% share, including wings and some fuselage parts. 65% of development cost was covered by West Germany; Italy covered 30% and Spain 5%. There would be assembly lines in all three countries, all of them set up by German companies with German production machinery. With many systems subject to US regulations, nobody expected any chance to export a significant number of the airplane; if completed, the type would compete against F-18L and Lavi, so the US would likely veto any sale outside of NATO. To the Germans, where weapons exports of any kind were highly unpopular, this did not matter much anyway. In 1989, the plane was officially dubbed Sturmvogel (Stormbird). The type was called Alcione (Kingfisher) in Italian and Halcon (also Kingfisher) in Spanish; apparently, the German name was wrongly translated by the Italians, and the wrong translation was carried over by the Spanish.

The first of seven prototypes was rolled out in October 1991 in Munich, two months after the successful coup against Gorbachev led by KGB chairman Kryuchkov and Minister of the Interior Pugo. The Soviet Junta had won popular support by pledging to prevent German re-unification, and staunchly refused to sign the 2+4-treaty restoring full German national sovereignty, which was a prerequisite for re-unification. With over 100.000 soldiers stationed in East Germany, they forced the East German government to close the borders again. The Junta also asserted Soviet rule in the Baltic and forced the Czech government to allow the return of substantial Soviet forces in order to keep open lines of communication with East Germany. This was no longer possible through Poland; although the Poles detested the notion of German re-unification, they made abundantly clear that they would fight to the last drop of blood if the Russians ever came back, under whatever pretense. Hungary was also lost to the Soviets, and Rumania was in a state of open civil war. Any Soviet attempt to solidify their position was met with more unrest, and living standard in the Soviet Union itself plummeted to early post-war levels as literally every available ruble went to the military. When the USA ignored furious Soviet demands to leave Saddam Hussein alone after his invasion of Kuwait and crushed the Iraqi military early in 1991, the cold war was back in force, and the fact that the Soviet Union was little more than a zombie in imminent danger of collapse made the probability of it going hot more likely than ever.

Such was the political climate when Sturmvogel’s second prototype made its first flight in March 1992. The test programme was conducted with urgency, revealing few problems. The planes displayed splendid maneuverability and good handling, but needed some structural strengthening, increasing empty weight to 9.050 kilograms. With basic air-to-air armament and 4.000 kilograms of internal fuel, normal take-off weight was 14.200 kilograms. Their MTU-built F404-GE-402 engines provided 78 kN each on burner, equaling a thrust/weight ratio of 1,1. Mock air-to-air combat with a Rafale prototype placed the German machine at a slight advantage; it however lacked Rafale’s built-in omnirole capabilities. The test program ran for three years; the series standard was presented in May 1994. By that time, Yugoslavia was racked by a savage civil war, in which the Serbs held the upper hand against anyone else due to massive Soviet backing, with no one daring to help the insurgents. East Germany was practically a prison. The elections scheduled for 1994 were called off by the Soviets and postponed infinitely. Poland was in a state of near constant maximum alert. The clinically dead Soviet Union desperately clung to life, and CPSU chairman Pugo weekly trumpeted his determination to defend what was left of their sphere of influence with teeth, claws and nukes. Under such conditions, the West had little alternative than ready itself for the day the status quo was no longer tenable. Sturmvogel was only one of many priority arms projects of that era; West Germany’s defense budget reached a hundred billion marks in 1994, and the draft was extended to twenty-one months that year. The first Sturmvogel series production line – the Spanish one, as Spain had the most urgent requirement – was opened that year, and the first Spanish production aircraft was handed over to the EdA in 1996. That same year, Italy also received their first series machine, Germany following in 1997. By that time, day X had come, and to everyone’s surprise, the Soviet Union died with a whimper instead of a bang. Within a few weeks during the summer of 1996, it collapsed under the weight of its debts and economic rot like a leaky balloon. Union level institutions just stopped working, state employees were no longer paid, and soldiers went simply home. Unlike 1990, there was no fight left in the old guard, which dissolved right along with the Union itself. Only Pugo had the energy to at least put a bullet through his head.

By the time the first German squadron of Sturmvogels reached IOC late in 1998, there were calls to cancel the whole project (among many, many others) to free money for rebuilding East Germany. But alas, the Kohl government had guaranteed the purchase in order to speed up development, so the planes would have to be paid for even if they were not delivered; grudgingly, the Schröder government kept taking delivery of an airplane they did not really want. On the plus side, the contract contained a fixed system price of 65 million dollars, only little more than the single-engine Lavi and much less than Rafale, and the combination of good test results and relative affordability attracted foreign buyers. Denmark, like Italy, needed to replace its fleet of F-13s, and placed an order over 64 machines in 1996; Austria ordered 24 units in 1997 to replace her fleet of Saab Viggens. The biggest success was a Turkish order for no less than 180 machines in three batches, placed between 1998 and 2004, to replace all remaining F-13s and F-5s. They were assembled in Turkey by TUSAS. In order to quickly process the export orders, deliveries to the West German and Spanish Air Forces were slowed down, which was considered acceptable given the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Austrian and Danish Sturmvogels thus were assembled in Germany and delivered between 2000 and 2009. When the Croats established an independent state in the 1998/9 war after Soviet backing for Serbia had disappeared and Yugoslavia was dissolved, West Germany was one of the first nations to officially recognize them, and the German government decided to hand over 28 Sturmvogels from ongoing production to Croatia, cutting German acquisition to 238. In 2000, Portugal ordered 36 machines, becoming the last F-13 user to replace that type with the Sturmvogel. They were built by CASA. A 2002 order for 28 units by the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force – the only order outside NATO which was not vetoed by the USA – was processed by Alenia in 2004/5. After that, no further orders were secured. Interest by Saudi-Arabia was expressed, but vetoed by the German government because of a perceived threat towards Israel. In Belgium and Greece, the type was evaluated, but Rafale was chosen in 2001 and 2003, respectively. Interest by Taiwan was waved off by all partner nations in order to avoid trouble with China. Attempts to sell the plane to Malaysia, Thailand, Morocco, Kuwait and the UAE were blocked by US veto; all these nations except Morocco subsequently bought US fighters. More recent Turkish attempts to sell planes to Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan also fell prey to US intervention. After the 2008 financial crash, it was obvious that the type’s production run was over and no further orders would come in. The European consortium needed till 2014 to process all orders; the Italian production line was shut down in 2005, the German and Spanish ones in 2009 and the Turkish in 2014, concluding twenty years of series production after 850 units produced, averaging 42 units per year. Of these, 352 were built in Germany, 192 in Italy, 180 in Turkey and 126 in Spain.

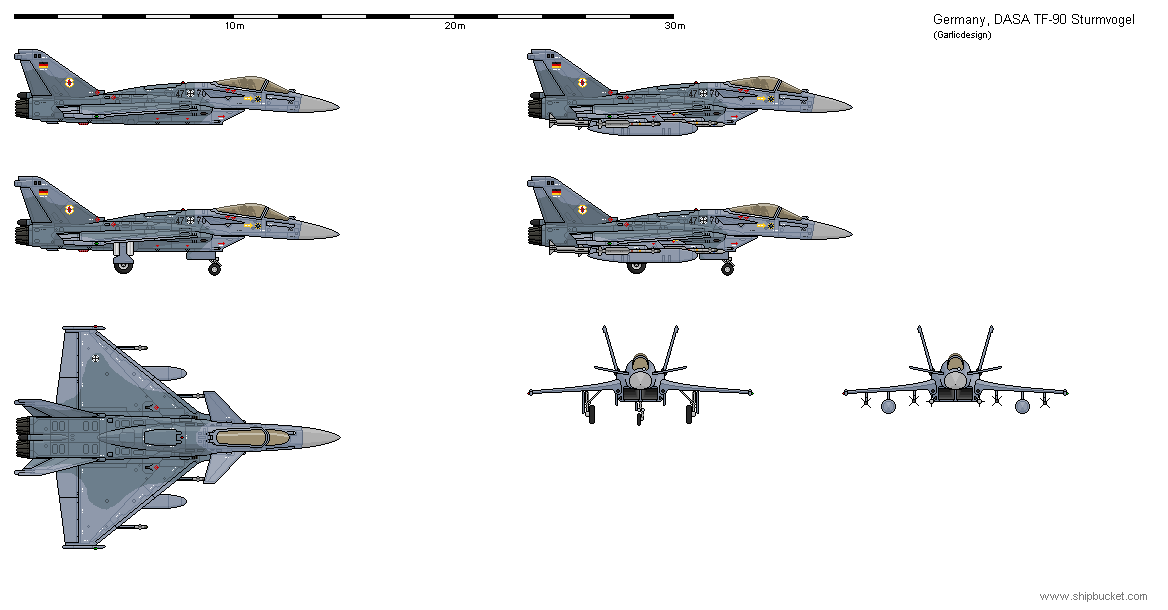

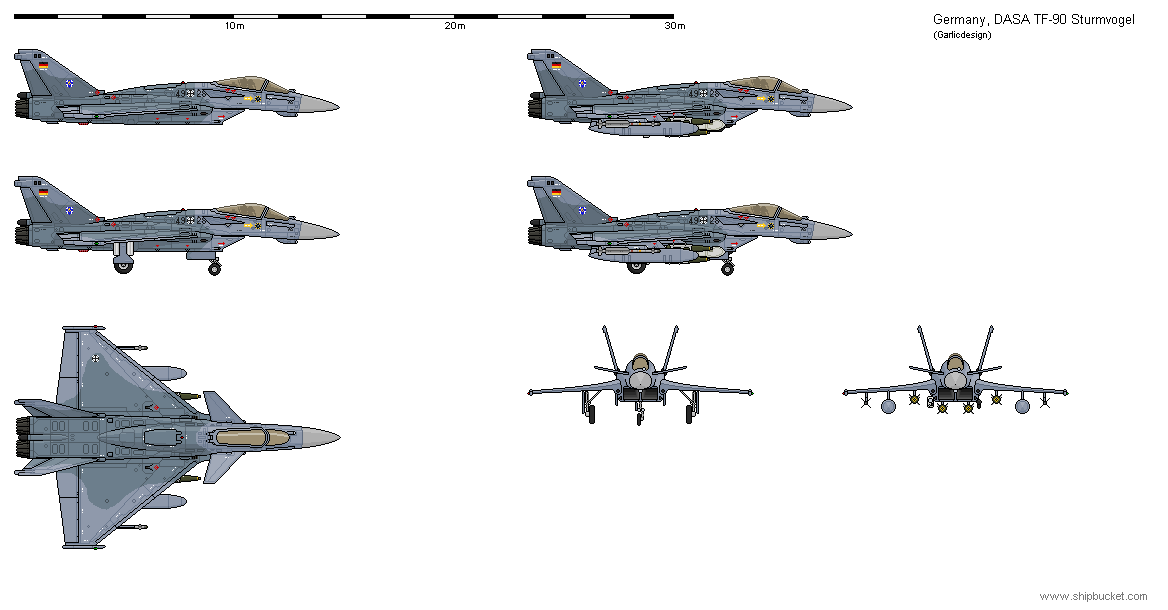

Deliveries of 238 units to Germany lasted from 1997 to 2009; the last Mirage F.4 was retired in 2005. The first of nine Sturmvogel squadrons (eight fighter squadrons and one OCU) achieved FOC in 2000, at that time armed with AMRAAM and Sidewinder missiles. As delivered, no German machine had air-to-ground capabilities.

The Sturmvogel airframe was designed for a twenty-five year life cycle; by the time the last machine was delivered, the first ones were due for mid-life refurbishment. Air-to-air armament was upgraded with IRIS-T dogfight missiles from 2003 and Meteor BVRAAMS from 2015. Of 229 units available in 2010 (three had been lost during the Yugoslav war of dissolution, all by SAMs, against four air-to-air kills of Serbian machines; six were lost in accidents), 212 were refurbished between 2010 and 2014. They were fitted with improved avionics, helmet and voice control, automated datalink, a completely new radar with a passive channel with limited capabilities against Stealth aircraft, air-to-ground targeting systems, and the ability to employ Polyphem missiles, Taurus cruise missiles, LGBs and GPS-guided JDAM bombs. Two more hard points were added, weapons load increased to 5.000 kilograms.

By 2020, they are the Luftwaffe’s true backbone. During the 2000s, the Germans cut down the size of their armed forces by about half. The number of Sturmvogel squadrons remained at nine, but of the sixteen Tornado squadrons (eight bomber, four recce, two SEAD and two OCU), only seven remained, and the six Donnerkeil ground-attack squadrons were retired without replacement. These force reductions required the Sturmvogel to take over the air-to-ground role. By 2015, all eight active Sturmvogel squadrons are air-to-ground capable; that year, squadron size was cut from 18 to 14, and the oldest 45 units were mothballed. During 2021, they were condemned for cannibalization, so the remaining force of 161, of which 126 are assigned to active squadrons, can be kept aloft for at least ten more years. While the Tornadoes are in the process of being replaced by Thiarian-designed stealth planes, Franco-German plans to produce a Sturmvogel replacement in the shape of FCAS by 2030 have been revealed as unduly optimistic. The Luftwaffe currently assumes they won’t see any serial FCAS prior to 2038, so they will have to employ the Sturmvogel for another seventeen years. By that time, the newest airframes will be 29 years old, and the oldest ones - which are mostly conversion trainers - up to 36.

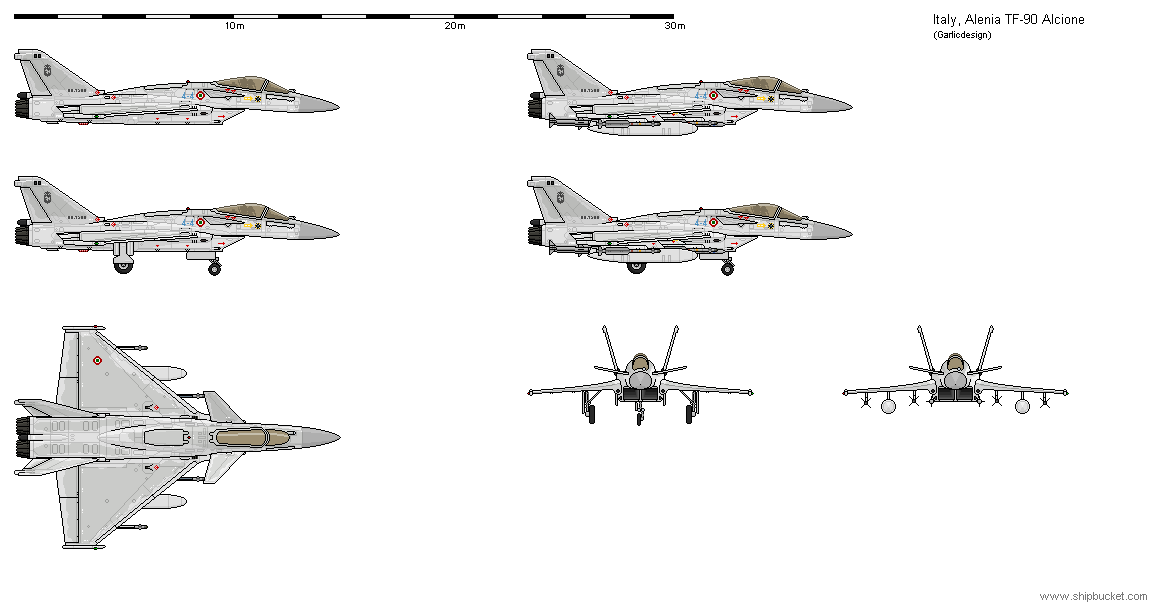

The Italian Air force received 164 units between 1996 and 2002, at a significantly faster pace than the Luftwaffe, because no Italian-built machines were diverted to other customers. Italy thus became the type’s first user to complete deliveries. They were armed with Idra and Sidewinder missiles; IRIS-T was introduced from 2005, and Meteor from 2018. Alciones have seen action during the Libyan civil war, claiming three kills (one MiG-29 and two helicopters) against zero losses. The Italian Air Force never substantially modernized their Alciones; being a level-1-partner both in America’s F-35 programme and the British/Recherchean Hale Firebolt programme – the latter expected available ten years earlier than FCAS – they expect to receive a 5th generation replacement by 2027, when their planes will be between 27 and 31 years old. 121 units are in service as of 2022 and equip four fighter squadrons and an OCU; another 20 are mothballed.

The Spanish Air Force was supplied with 90 Halcon II fighters at a slow rate of eight per year between 1995 and 2005. Originally armed with AMRAAM and Sidewinder, they converted to Meteor and IRIS-T at the same time as the Germans. Like the Italians, the Spanish did not add ground attack capabilities to their Halcons, which mostly had fiscal reasons. Being a level-2-partner in the FCAS program, the Spanish won’t get a replacement anytime soon, so their 76 remaining Halcons are in for a service extension modernization, which was ordered in 2020, to be effected between 2023 and 2025, refurbishing them to zero flying hours and replacing radars and electronics, but without air-to-ground capabilities.

The Turkish Air Force, which calls the type Yelkovan (Kingfisher, again), has the youngest and best proven fleet, and at 163 units in service with eight squadrons currently also the largest. Although they are still armed with obsolescent US sourced AAMs, they have repeatedly seen combat during the Syrian civil war, and had clashes with Greek Mirage 2000s and Rafales, and Russian MiG-29s and Su-27s. Yelkovan pilots have claimed a total of 39 kills, mostly Syrian Air Force jets. According to current plans, the Yelkovan will be replaced by a domestic Turkish 5th generation fighter at some point in the 2030s; whether this is realistic remains to be seen.

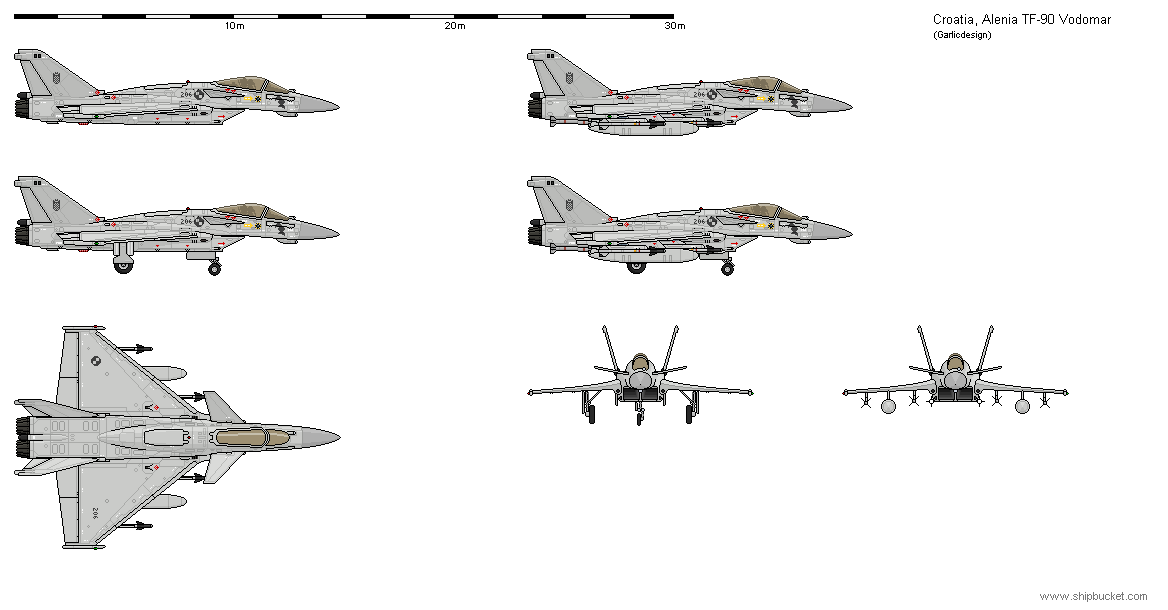

The 28 Croatian machines - named Vodomar (Kingfisher) – were diverted from German production and delivered from 2000 through 2002. Like the German Sturmvogels, they were air-to-air only, carrying standard US equipment; the Germans delivered additional US missiles to Croatia after replacing them with newer domestic ones, so the Croatians are amply stocked and will use AMRAAM and Sidewinder for the foreseeable future. All Croatian planes received the same air-to-ground modifications as the German units, but not the new radar. Croatia and Oman are the only users who have never had to write off a single plane, despite several clashes with Serbian MiGs; their 28 machines equip two 12-ship squadrons. There are no current plans to replace the type in Croatian service.

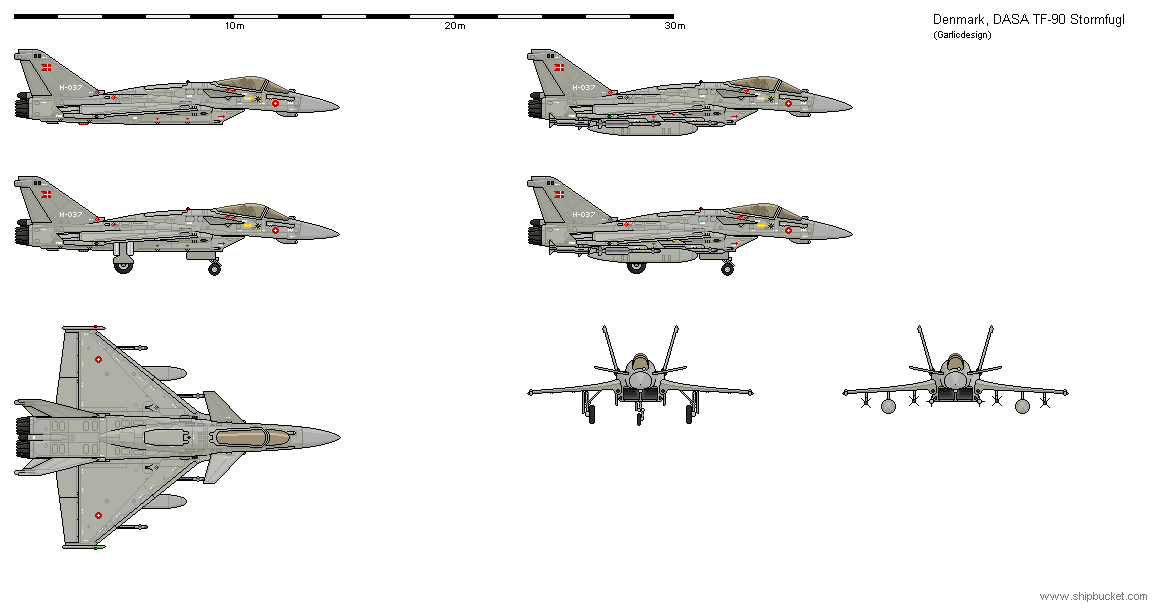

The Royal Danish Air Force received their 64 Stormfugls beginning in 2000 at an average rate of eight per year from ongoing German production; the last machine was delivered in 2007. They were the first version with some basic built-in air-to-ground capability, and so far the only one capable of firing NSM AShMs, as they are the only fast jets of the Danish Air Force and had to perform every mission at hand. The Danes introduced IRIS-T and Meteor in 2012 and 2021, respectively; between 2015 and 2018, all Danish machines received the same upgrades as the German Sturmvogels.

Austria was supplied with 24 Sturmvogels from German production between 2006 and 2009 at a very slow rate of six per year. They were air-to-ground capable from the start and received IRIS-T from 2014, but have not been modernized yet. Austria has so far not ordered any Meteor missiles. There are currently no plans for replacement; they are however criticized for their high operating cost, and it was repeatedly proposed to retire them without replacement. Fortunately, Austrian governments have fallen so quickly to an embarrassing series of scandals, they simply had no opportunity, and given Russia’s current rampage, calls for their retirement have lately fallen silent.

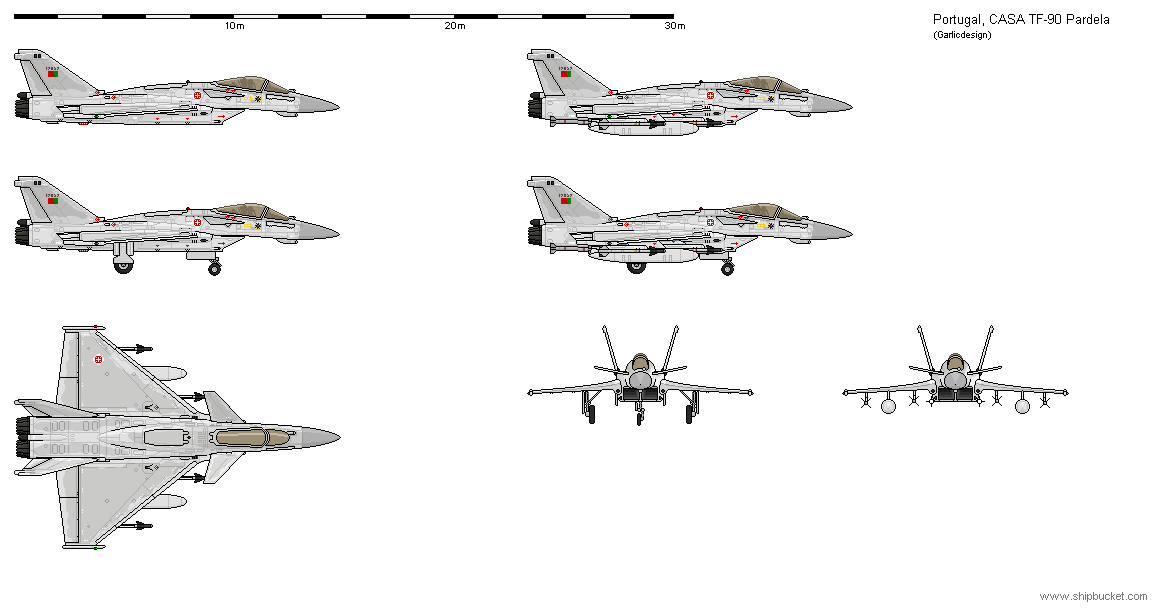

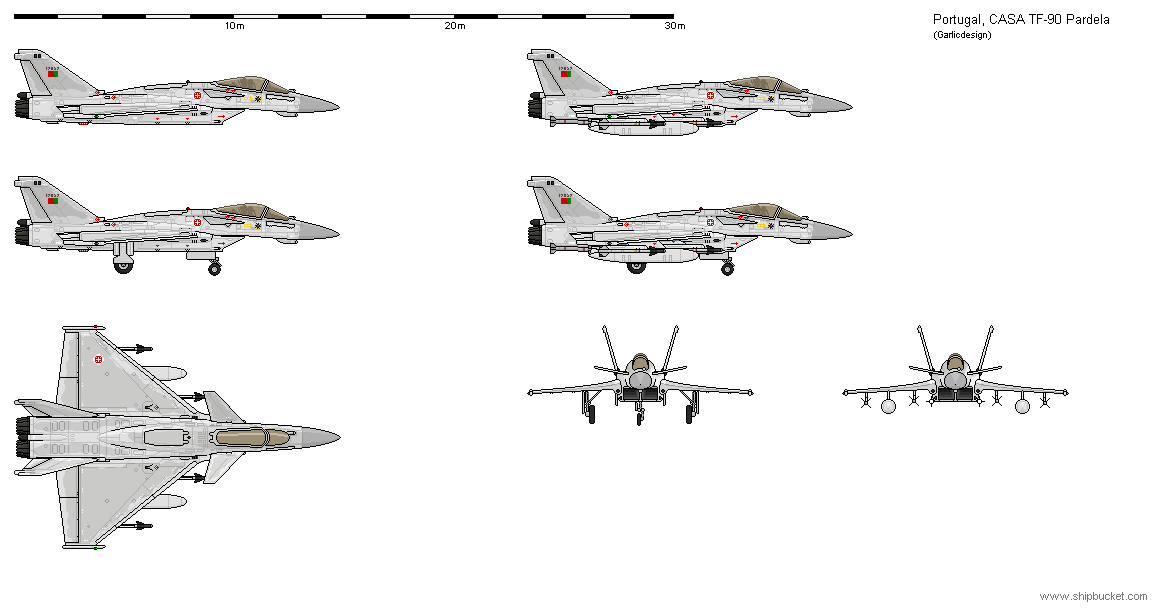

The 36 Portuguese machines (called Pardela/Stormbird) were delivered from Spain in 2006 through 2009 after Spain’s own production run was over. Equipment-wise, they are identical to the Croatian planes, and like Croatia, Portugal has so far been unable to afford more modern AAMs than AMRAAM and Sidewinder. 33 remain in service and equip two squadrons. Although they are air-to-ground capable, they are rarely used in this capacity.

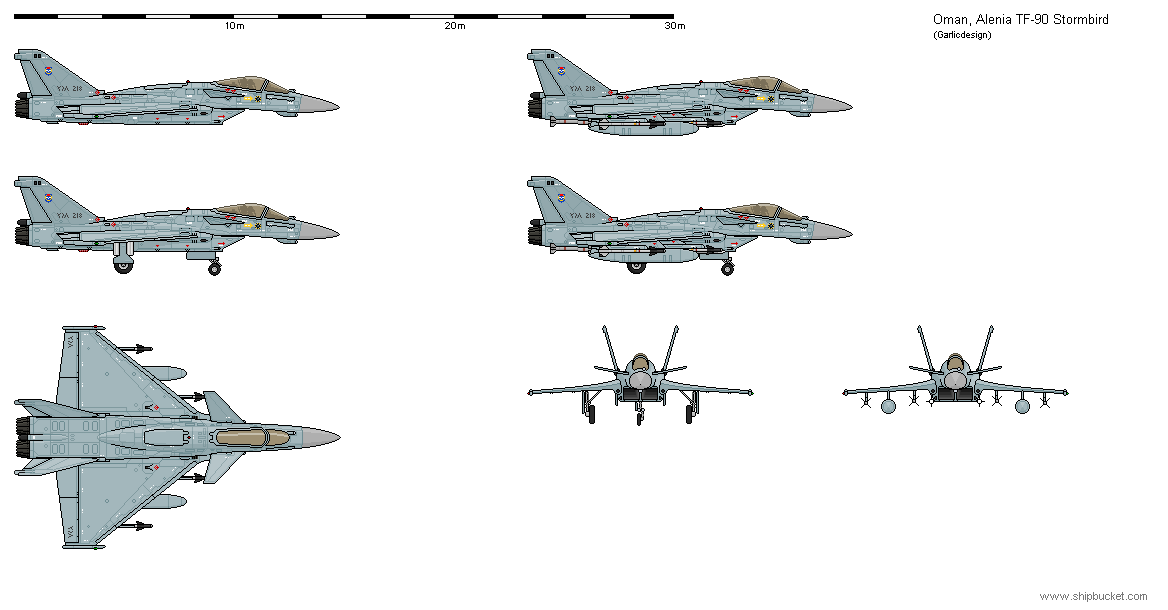

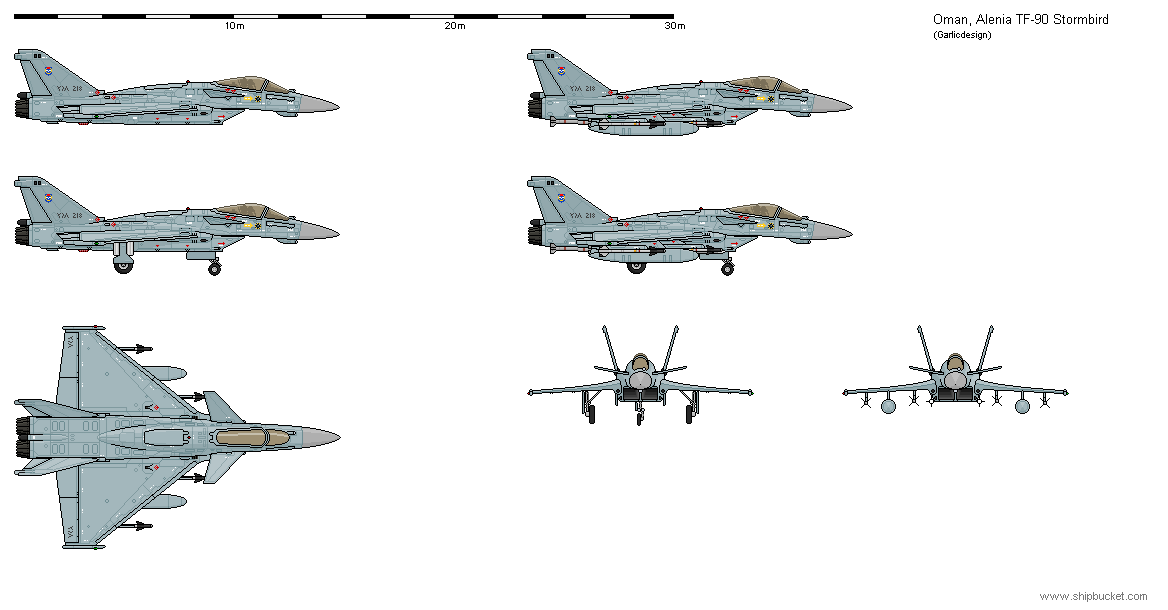

The final batch of 28 Italian-built Alciones went to the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force between 2007 and 2009. They were identical to the Italian machines, but fitted with full air-to-ground capability before delivery. Ironically, it is an Omani pilot who currently carries the mantle of Sturmvogel Top Ace, after shooting down two Yemenite planes and an Iranian one.

Cheers

GD

DASA/Alenia/CASA TF-90 Sturmvogel / Alcione / Halcon II

In 1983, a five-national (Great Britain, France, West Germany, Italy and Spain) project for design and production of a Generation 4.5 Fighter to equip Europe’s Air Forces in the 1990s was launched. France, Germany and Great Britain all had designs for canard twinjets of similar size, which were to be merged into a single type to satisfy a joint initial requirement for a thousand machines. Within two years, politics tore the project apart. France, Great Britain and Germany all wanted project leadership; France and Great Britain each wanted to provide the engines; and both nations wanted carrier capability, which nobody else needed. The French left the project in 1985 and proceeded to independently develop Rafale, and Margaret Thatcher killed it dead with her 1985 decision to adopt the Hale Tempest with British-built radar, avionics, weapons and RB.246 engines for both the RAF and the FAA, eliminating British requirement for another fighter for the next twenty years. The Germans, Italians and Spaniards were thus left with a German concept study (TKF-90 dating to 1979), no engine and no avionics kit. Sensible people might have called it a day, but the German government had already spent two billion marks of development expenses (half of it swallowed by the Brits and French) and decided to put TKF-90 into the air, if only to prove that they could. They were also bribed. With the requirement for carrier capability gone, the plane’s size and weight could be reduced, although the initial requirement for eight tons empty weight proved impossible to meet. The dorsal spine of TKF-90 vanished, replaced by a Flanker-ish hump with large central air brake and a bubble canopy, providing more space for fuel and electronics as well as better pilot view. Simplicity was also a factor: Fixes air intakes were fitted, limiting top speed to Mach 1,8 regardless of engine power. The originally planned thrust vector control option was dropped, as were air-to-ground capabilities, making the plane a single-role air superiority fighter. The final design retained twin horizontal stabilizers for maximum maneuverability, but moved the canards from the very bow to a position directly above the wing roots, just like Rafale and the Israeli Lavi. This allowed for better maneuverability at low altitudes and speeds, a particularly important feature for the Germans who needed to operate in an environment saturated with enemy SAMs. The prior focus on high-speed, high altitude performance had largely been a British demand (the Italians and Spaniards would still have liked it, but with German money keeping the whole project aloft, they were overruled). The somewhat more stable aerodynamic layout also allowed the plane to stay aloft if the canards were incapacitated by battle damage, which would have been questionable with the former layout. To minimize expenses, off-the shelf systems were to be used wherever possible, in a modular arrangement that would allow later upgrades. Thus, rather than developing an all-new engine, MTU acquired a license for the well-proven GE F404. The MSD-2000 radar was a much improved AESA version of the APG-65, built by Alenia, which also provided the avionics package. Armament consisted of two fixed 27mm Mauser cannon in the wing roots with 150 rpg, conformal bays for four AMRAAMs and six hard points (two of them wet) for an external weapons load of 4.000 kilograms, this low figure reflecting the plane’s single-role fighter nature.

As development work proceeded, the partner nations agreed on the scope of work share in 1987. Germany, with a requirement of 264 planes to replace the Mirage F.4 one for one after that type reached the end of its designed twenty-year service life in 1996, would lead the project and provide 48% of the parts: Engines including fuel system and aerial refueling gear, guns, running gear, all auxiliary machinery, all control surfaces and all production plant equipment. Italy’s requirement for 164 machines, replacing the Lockheed F-13 from 1995, translated into a share of 32%; the Italians would provide radar, avionics including the software package, cockpit interior including instruments and ejector seat, and most of the fuselage. Spain’s requirement for 90 machines, replacing the Mirage F.1 from 1994, gave them a 20% share, including wings and some fuselage parts. 65% of development cost was covered by West Germany; Italy covered 30% and Spain 5%. There would be assembly lines in all three countries, all of them set up by German companies with German production machinery. With many systems subject to US regulations, nobody expected any chance to export a significant number of the airplane; if completed, the type would compete against F-18L and Lavi, so the US would likely veto any sale outside of NATO. To the Germans, where weapons exports of any kind were highly unpopular, this did not matter much anyway. In 1989, the plane was officially dubbed Sturmvogel (Stormbird). The type was called Alcione (Kingfisher) in Italian and Halcon (also Kingfisher) in Spanish; apparently, the German name was wrongly translated by the Italians, and the wrong translation was carried over by the Spanish.

The first of seven prototypes was rolled out in October 1991 in Munich, two months after the successful coup against Gorbachev led by KGB chairman Kryuchkov and Minister of the Interior Pugo. The Soviet Junta had won popular support by pledging to prevent German re-unification, and staunchly refused to sign the 2+4-treaty restoring full German national sovereignty, which was a prerequisite for re-unification. With over 100.000 soldiers stationed in East Germany, they forced the East German government to close the borders again. The Junta also asserted Soviet rule in the Baltic and forced the Czech government to allow the return of substantial Soviet forces in order to keep open lines of communication with East Germany. This was no longer possible through Poland; although the Poles detested the notion of German re-unification, they made abundantly clear that they would fight to the last drop of blood if the Russians ever came back, under whatever pretense. Hungary was also lost to the Soviets, and Rumania was in a state of open civil war. Any Soviet attempt to solidify their position was met with more unrest, and living standard in the Soviet Union itself plummeted to early post-war levels as literally every available ruble went to the military. When the USA ignored furious Soviet demands to leave Saddam Hussein alone after his invasion of Kuwait and crushed the Iraqi military early in 1991, the cold war was back in force, and the fact that the Soviet Union was little more than a zombie in imminent danger of collapse made the probability of it going hot more likely than ever.

Such was the political climate when Sturmvogel’s second prototype made its first flight in March 1992. The test programme was conducted with urgency, revealing few problems. The planes displayed splendid maneuverability and good handling, but needed some structural strengthening, increasing empty weight to 9.050 kilograms. With basic air-to-air armament and 4.000 kilograms of internal fuel, normal take-off weight was 14.200 kilograms. Their MTU-built F404-GE-402 engines provided 78 kN each on burner, equaling a thrust/weight ratio of 1,1. Mock air-to-air combat with a Rafale prototype placed the German machine at a slight advantage; it however lacked Rafale’s built-in omnirole capabilities. The test program ran for three years; the series standard was presented in May 1994. By that time, Yugoslavia was racked by a savage civil war, in which the Serbs held the upper hand against anyone else due to massive Soviet backing, with no one daring to help the insurgents. East Germany was practically a prison. The elections scheduled for 1994 were called off by the Soviets and postponed infinitely. Poland was in a state of near constant maximum alert. The clinically dead Soviet Union desperately clung to life, and CPSU chairman Pugo weekly trumpeted his determination to defend what was left of their sphere of influence with teeth, claws and nukes. Under such conditions, the West had little alternative than ready itself for the day the status quo was no longer tenable. Sturmvogel was only one of many priority arms projects of that era; West Germany’s defense budget reached a hundred billion marks in 1994, and the draft was extended to twenty-one months that year. The first Sturmvogel series production line – the Spanish one, as Spain had the most urgent requirement – was opened that year, and the first Spanish production aircraft was handed over to the EdA in 1996. That same year, Italy also received their first series machine, Germany following in 1997. By that time, day X had come, and to everyone’s surprise, the Soviet Union died with a whimper instead of a bang. Within a few weeks during the summer of 1996, it collapsed under the weight of its debts and economic rot like a leaky balloon. Union level institutions just stopped working, state employees were no longer paid, and soldiers went simply home. Unlike 1990, there was no fight left in the old guard, which dissolved right along with the Union itself. Only Pugo had the energy to at least put a bullet through his head.

By the time the first German squadron of Sturmvogels reached IOC late in 1998, there were calls to cancel the whole project (among many, many others) to free money for rebuilding East Germany. But alas, the Kohl government had guaranteed the purchase in order to speed up development, so the planes would have to be paid for even if they were not delivered; grudgingly, the Schröder government kept taking delivery of an airplane they did not really want. On the plus side, the contract contained a fixed system price of 65 million dollars, only little more than the single-engine Lavi and much less than Rafale, and the combination of good test results and relative affordability attracted foreign buyers. Denmark, like Italy, needed to replace its fleet of F-13s, and placed an order over 64 machines in 1996; Austria ordered 24 units in 1997 to replace her fleet of Saab Viggens. The biggest success was a Turkish order for no less than 180 machines in three batches, placed between 1998 and 2004, to replace all remaining F-13s and F-5s. They were assembled in Turkey by TUSAS. In order to quickly process the export orders, deliveries to the West German and Spanish Air Forces were slowed down, which was considered acceptable given the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Austrian and Danish Sturmvogels thus were assembled in Germany and delivered between 2000 and 2009. When the Croats established an independent state in the 1998/9 war after Soviet backing for Serbia had disappeared and Yugoslavia was dissolved, West Germany was one of the first nations to officially recognize them, and the German government decided to hand over 28 Sturmvogels from ongoing production to Croatia, cutting German acquisition to 238. In 2000, Portugal ordered 36 machines, becoming the last F-13 user to replace that type with the Sturmvogel. They were built by CASA. A 2002 order for 28 units by the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force – the only order outside NATO which was not vetoed by the USA – was processed by Alenia in 2004/5. After that, no further orders were secured. Interest by Saudi-Arabia was expressed, but vetoed by the German government because of a perceived threat towards Israel. In Belgium and Greece, the type was evaluated, but Rafale was chosen in 2001 and 2003, respectively. Interest by Taiwan was waved off by all partner nations in order to avoid trouble with China. Attempts to sell the plane to Malaysia, Thailand, Morocco, Kuwait and the UAE were blocked by US veto; all these nations except Morocco subsequently bought US fighters. More recent Turkish attempts to sell planes to Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan also fell prey to US intervention. After the 2008 financial crash, it was obvious that the type’s production run was over and no further orders would come in. The European consortium needed till 2014 to process all orders; the Italian production line was shut down in 2005, the German and Spanish ones in 2009 and the Turkish in 2014, concluding twenty years of series production after 850 units produced, averaging 42 units per year. Of these, 352 were built in Germany, 192 in Italy, 180 in Turkey and 126 in Spain.

Deliveries of 238 units to Germany lasted from 1997 to 2009; the last Mirage F.4 was retired in 2005. The first of nine Sturmvogel squadrons (eight fighter squadrons and one OCU) achieved FOC in 2000, at that time armed with AMRAAM and Sidewinder missiles. As delivered, no German machine had air-to-ground capabilities.

The Sturmvogel airframe was designed for a twenty-five year life cycle; by the time the last machine was delivered, the first ones were due for mid-life refurbishment. Air-to-air armament was upgraded with IRIS-T dogfight missiles from 2003 and Meteor BVRAAMS from 2015. Of 229 units available in 2010 (three had been lost during the Yugoslav war of dissolution, all by SAMs, against four air-to-air kills of Serbian machines; six were lost in accidents), 212 were refurbished between 2010 and 2014. They were fitted with improved avionics, helmet and voice control, automated datalink, a completely new radar with a passive channel with limited capabilities against Stealth aircraft, air-to-ground targeting systems, and the ability to employ Polyphem missiles, Taurus cruise missiles, LGBs and GPS-guided JDAM bombs. Two more hard points were added, weapons load increased to 5.000 kilograms.

By 2020, they are the Luftwaffe’s true backbone. During the 2000s, the Germans cut down the size of their armed forces by about half. The number of Sturmvogel squadrons remained at nine, but of the sixteen Tornado squadrons (eight bomber, four recce, two SEAD and two OCU), only seven remained, and the six Donnerkeil ground-attack squadrons were retired without replacement. These force reductions required the Sturmvogel to take over the air-to-ground role. By 2015, all eight active Sturmvogel squadrons are air-to-ground capable; that year, squadron size was cut from 18 to 14, and the oldest 45 units were mothballed. During 2021, they were condemned for cannibalization, so the remaining force of 161, of which 126 are assigned to active squadrons, can be kept aloft for at least ten more years. While the Tornadoes are in the process of being replaced by Thiarian-designed stealth planes, Franco-German plans to produce a Sturmvogel replacement in the shape of FCAS by 2030 have been revealed as unduly optimistic. The Luftwaffe currently assumes they won’t see any serial FCAS prior to 2038, so they will have to employ the Sturmvogel for another seventeen years. By that time, the newest airframes will be 29 years old, and the oldest ones - which are mostly conversion trainers - up to 36.

The Italian Air force received 164 units between 1996 and 2002, at a significantly faster pace than the Luftwaffe, because no Italian-built machines were diverted to other customers. Italy thus became the type’s first user to complete deliveries. They were armed with Idra and Sidewinder missiles; IRIS-T was introduced from 2005, and Meteor from 2018. Alciones have seen action during the Libyan civil war, claiming three kills (one MiG-29 and two helicopters) against zero losses. The Italian Air Force never substantially modernized their Alciones; being a level-1-partner both in America’s F-35 programme and the British/Recherchean Hale Firebolt programme – the latter expected available ten years earlier than FCAS – they expect to receive a 5th generation replacement by 2027, when their planes will be between 27 and 31 years old. 121 units are in service as of 2022 and equip four fighter squadrons and an OCU; another 20 are mothballed.

The Spanish Air Force was supplied with 90 Halcon II fighters at a slow rate of eight per year between 1995 and 2005. Originally armed with AMRAAM and Sidewinder, they converted to Meteor and IRIS-T at the same time as the Germans. Like the Italians, the Spanish did not add ground attack capabilities to their Halcons, which mostly had fiscal reasons. Being a level-2-partner in the FCAS program, the Spanish won’t get a replacement anytime soon, so their 76 remaining Halcons are in for a service extension modernization, which was ordered in 2020, to be effected between 2023 and 2025, refurbishing them to zero flying hours and replacing radars and electronics, but without air-to-ground capabilities.

The Turkish Air Force, which calls the type Yelkovan (Kingfisher, again), has the youngest and best proven fleet, and at 163 units in service with eight squadrons currently also the largest. Although they are still armed with obsolescent US sourced AAMs, they have repeatedly seen combat during the Syrian civil war, and had clashes with Greek Mirage 2000s and Rafales, and Russian MiG-29s and Su-27s. Yelkovan pilots have claimed a total of 39 kills, mostly Syrian Air Force jets. According to current plans, the Yelkovan will be replaced by a domestic Turkish 5th generation fighter at some point in the 2030s; whether this is realistic remains to be seen.

The 28 Croatian machines - named Vodomar (Kingfisher) – were diverted from German production and delivered from 2000 through 2002. Like the German Sturmvogels, they were air-to-air only, carrying standard US equipment; the Germans delivered additional US missiles to Croatia after replacing them with newer domestic ones, so the Croatians are amply stocked and will use AMRAAM and Sidewinder for the foreseeable future. All Croatian planes received the same air-to-ground modifications as the German units, but not the new radar. Croatia and Oman are the only users who have never had to write off a single plane, despite several clashes with Serbian MiGs; their 28 machines equip two 12-ship squadrons. There are no current plans to replace the type in Croatian service.

The Royal Danish Air Force received their 64 Stormfugls beginning in 2000 at an average rate of eight per year from ongoing German production; the last machine was delivered in 2007. They were the first version with some basic built-in air-to-ground capability, and so far the only one capable of firing NSM AShMs, as they are the only fast jets of the Danish Air Force and had to perform every mission at hand. The Danes introduced IRIS-T and Meteor in 2012 and 2021, respectively; between 2015 and 2018, all Danish machines received the same upgrades as the German Sturmvogels.

Austria was supplied with 24 Sturmvogels from German production between 2006 and 2009 at a very slow rate of six per year. They were air-to-ground capable from the start and received IRIS-T from 2014, but have not been modernized yet. Austria has so far not ordered any Meteor missiles. There are currently no plans for replacement; they are however criticized for their high operating cost, and it was repeatedly proposed to retire them without replacement. Fortunately, Austrian governments have fallen so quickly to an embarrassing series of scandals, they simply had no opportunity, and given Russia’s current rampage, calls for their retirement have lately fallen silent.

The 36 Portuguese machines (called Pardela/Stormbird) were delivered from Spain in 2006 through 2009 after Spain’s own production run was over. Equipment-wise, they are identical to the Croatian planes, and like Croatia, Portugal has so far been unable to afford more modern AAMs than AMRAAM and Sidewinder. 33 remain in service and equip two squadrons. Although they are air-to-ground capable, they are rarely used in this capacity.

The final batch of 28 Italian-built Alciones went to the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force between 2007 and 2009. They were identical to the Italian machines, but fitted with full air-to-ground capability before delivery. Ironically, it is an Omani pilot who currently carries the mantle of Sturmvogel Top Ace, after shooting down two Yemenite planes and an Iranian one.

Cheers

GD

Re: Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

When Typhoon, MiG-29 and F-16 had embarrassing threesome.

Nobody expects the Imperial Inquisition!