Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

Moderator: Community Manager

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

Hello again!

Russian Carrier Aviation 1945 – 2020 (Thiariaverse edition)

1. The 1950s

In 1948, the Soviet Union was in possession of three aircraft carrier hulls: The badly damaged German Graf Zeppelin, the incomplete Japanese Kaimon and the fully operational Thiarian Feinics. The German ship was in a wretched state and offered no growth potential, so she was discarded and used up for trials in 1953. Feinics was commissioned for trials in 1950 and renamed Kraznaya Zvezda, with an air group consisting of WWII vintage La-11K and Su-6K aircraft and used to train carrier pilots and develop an operational doctrine. Kaimon was laid up to await a decision on her further use. Stalin was as determined as ever to create a Soviet Blue Water Navy to rival the might of the USN and ordered to complete Kaimon to a revised design heavily influenced by Feinics, and to build an enlarged copy of Feinics named Kronshtadt. That vessel was ten meters longer than Feinics, displaced 5.000 tons more and had a larger island with integral funnel and longer, if still hydraulic catapults. Two additional ships were planned to be laid down in 1955, after initial experiences with the first two ships could be evaluated. The rebuild of Kaimon ran into trouble due to her very flimsy construction and ergonomic unsuitability for cold climates and was abandoned in 1954 after very little progress, but Kronshtadt was laid down in 1950, launched in 1953 and completed in 1956, fully on schedule. Even Khrushchev, who did not believe in conventional forces and focused Soviet efforts on nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, approved Kronshtadt’s completion because she was so far advanced already that scrapping her would have been wasteful. By 1959, the Soviet Union thus was in possession of two conventionally powered straight-decked aircraft carriers. Kraznaya Zvezda was limited to aircraft of eight tons MTOW due to the limited power of her single catapult; Kronshtadt had two catapults capable of shooting fifteen tons each into the air. Thus, Kraznaya Zvezda was only ever used for training, and only Kronshtadt was capable of operating the new generation of Soviet carrierborne nuclear-capable heavy strike aircraft.

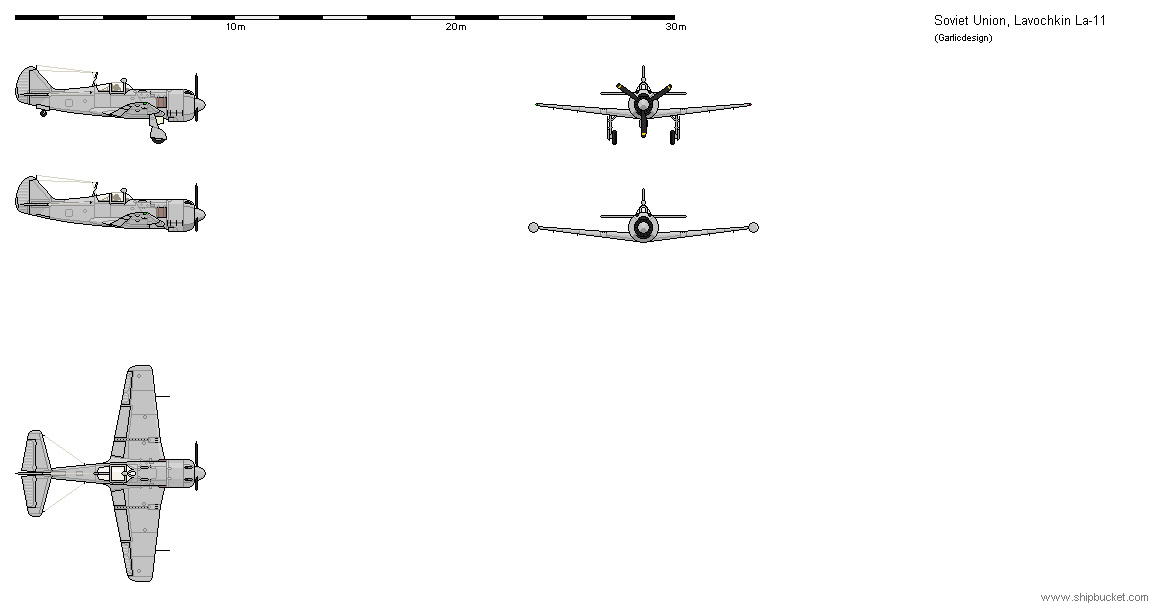

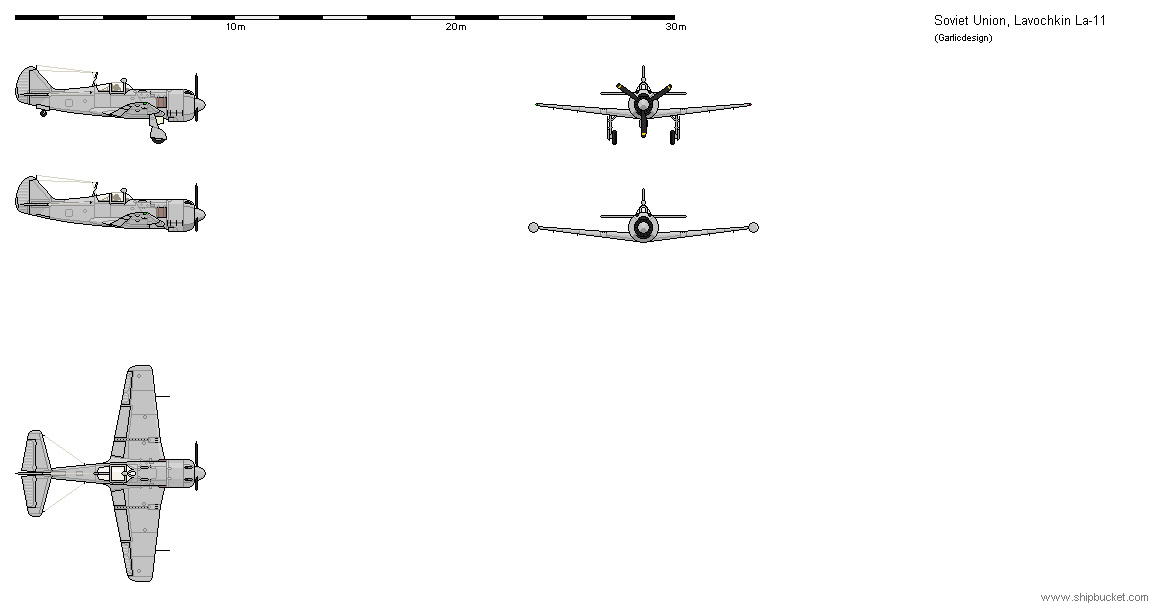

1.1. Lavochkin La-11K ‘Fang’

The first Soviet carrierborne fighter was a straightforward upgrade of the land-based La-11 and quite obsolete when Kraznaya Zvezda was commissioned in 1950. Adding arrestor hooks and catapult fittings did no good to the performance envelope of an already overweight design, and their fighting power was rather symbolic.

The Lavochkin fighters remained in service for five years till enough Yak-31s were available.

Although they never saw serious action, they were immensely valuable in developing carrier operation routines, at which the Soviets were complete virgins when the La-11 entered service.

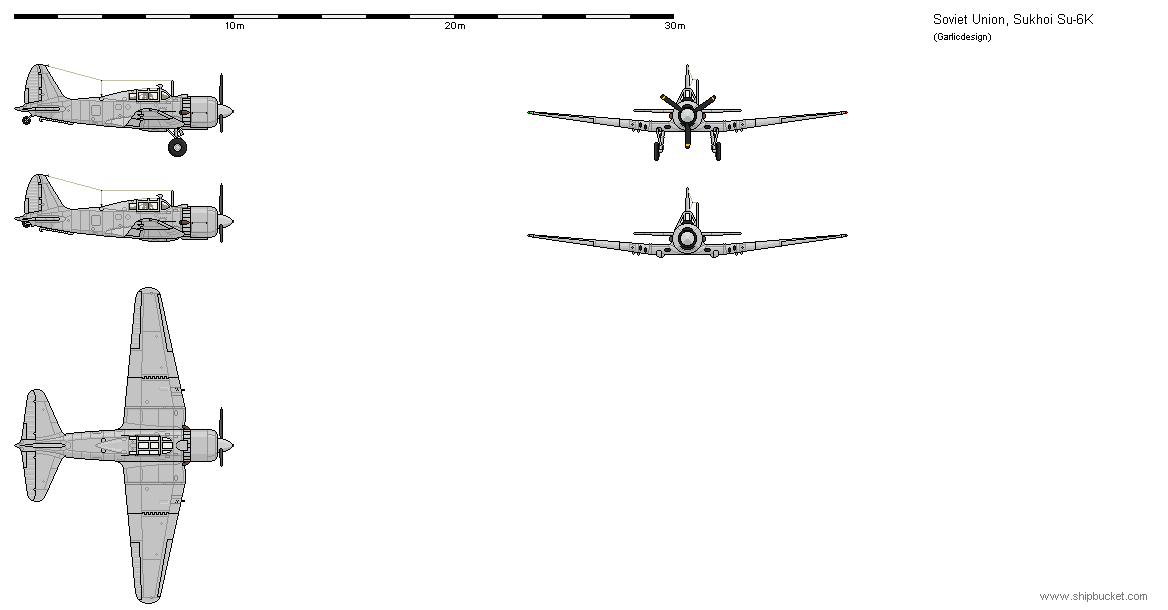

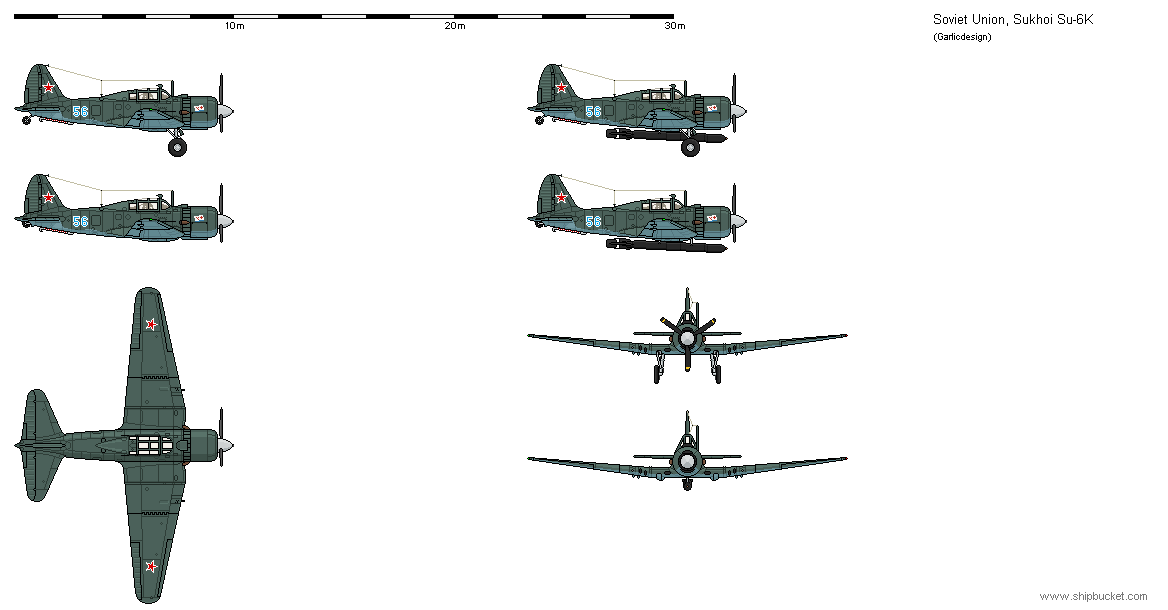

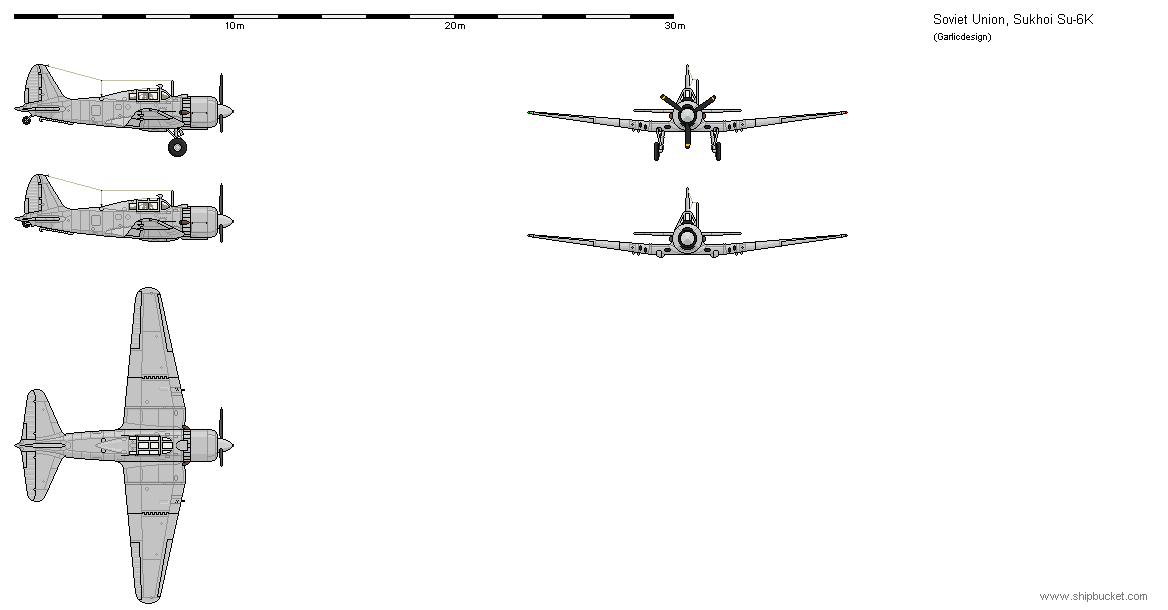

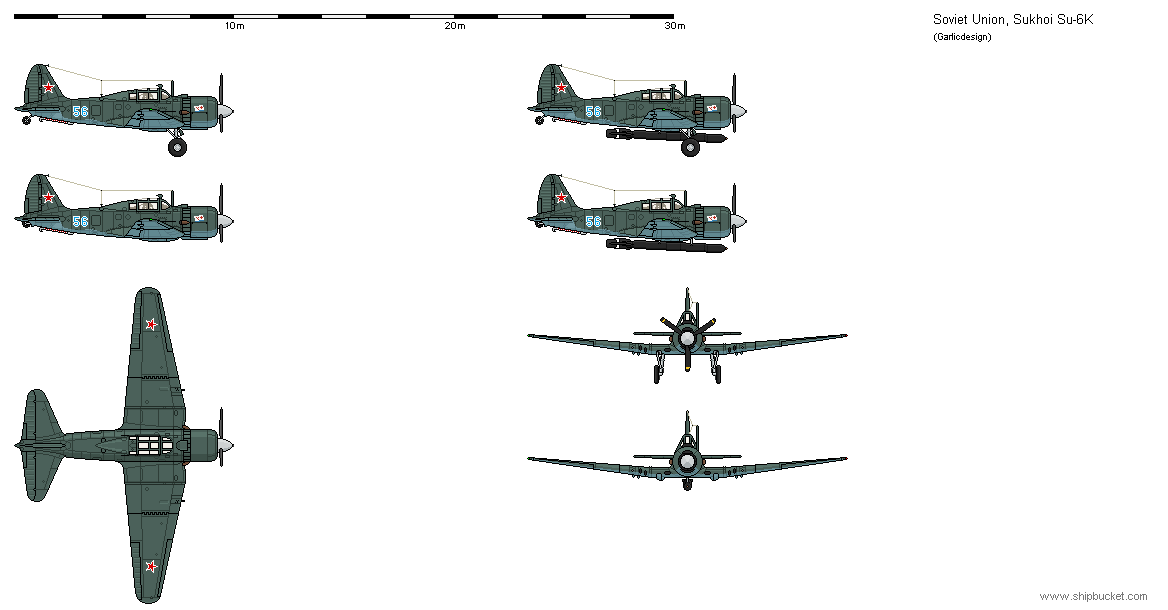

1.2. Sukhoi Su-6MK ‘Brick’

The Su-6M was a rather random choice for the naval strike and torpedo bomber role, whose only virtue was the use of the same ASh-82 engine also installed in the La-11. The type had been a backup for the Il-2, but never seen much production due to the lack of the originally planed M-71 engine and the unsuitability of the AM-42 that was substituted; the Ash-82 installed in the naval version was weaker than either, and eschewing armour protection was compensated by the added weight of catapult fittings, sea rescue gear and arrestor hooks.

The result was a seriously underpowered airplane which was unable to perform its assigned mission, resulting in the aptly chosen NATO reporting name Brick. The Su-6 only ever performed training operations and was replaced by the infinitely more capable Tu-18 as soon as possible.

By 1958, the last naval Su-6 was retired.

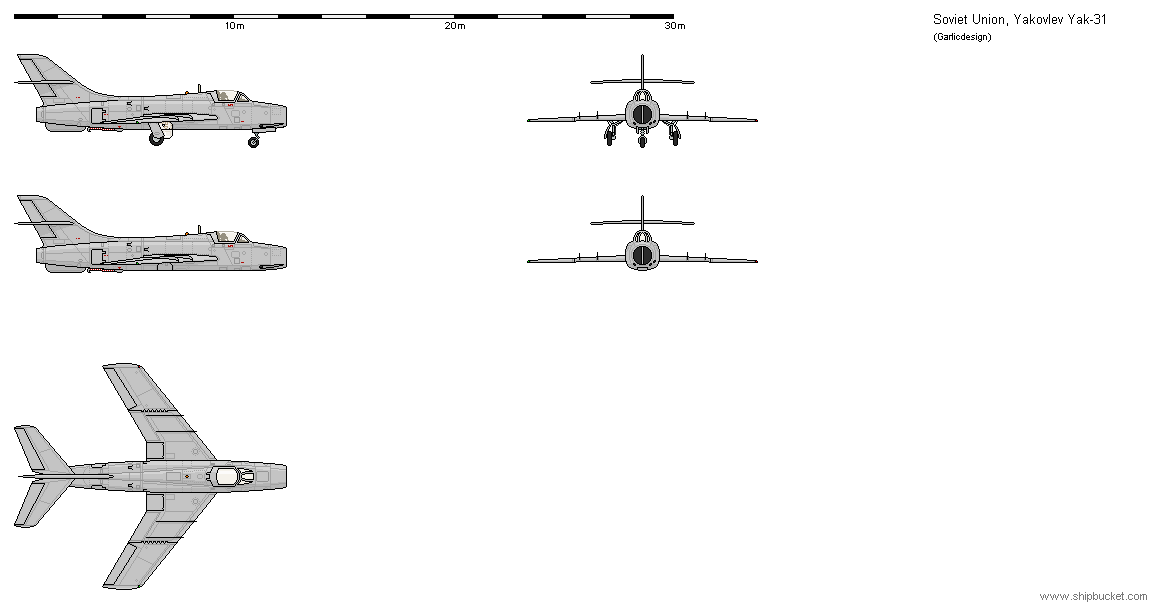

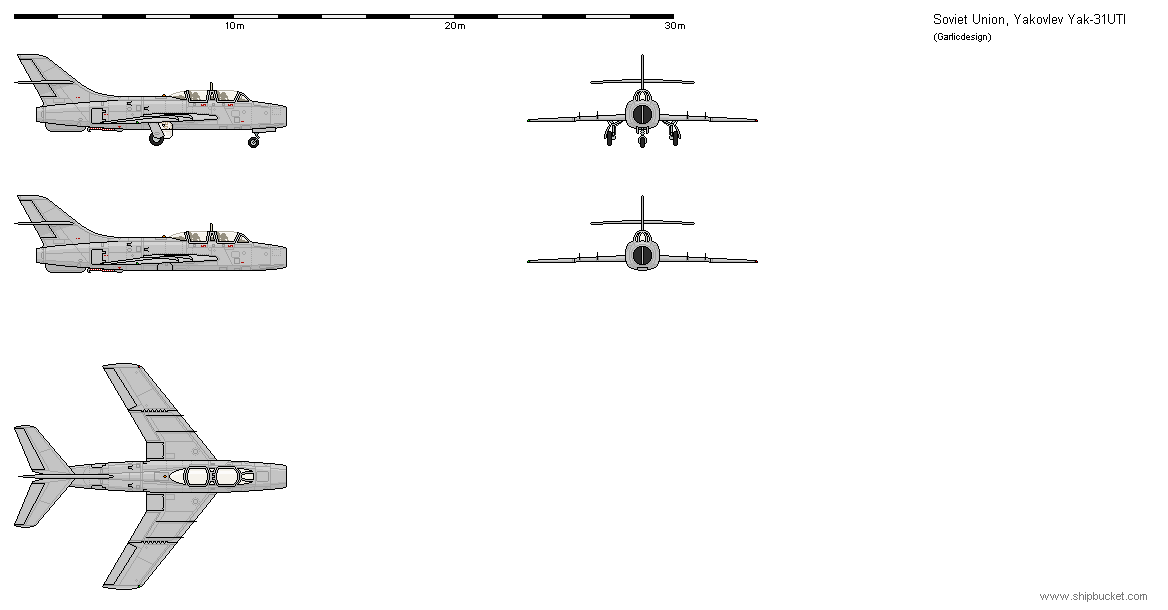

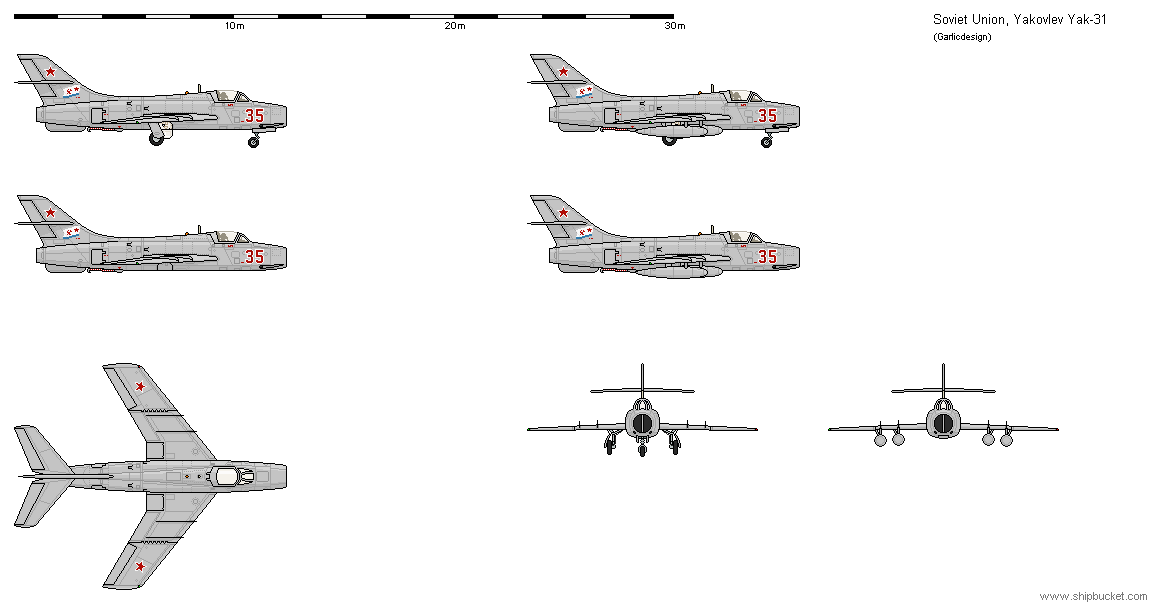

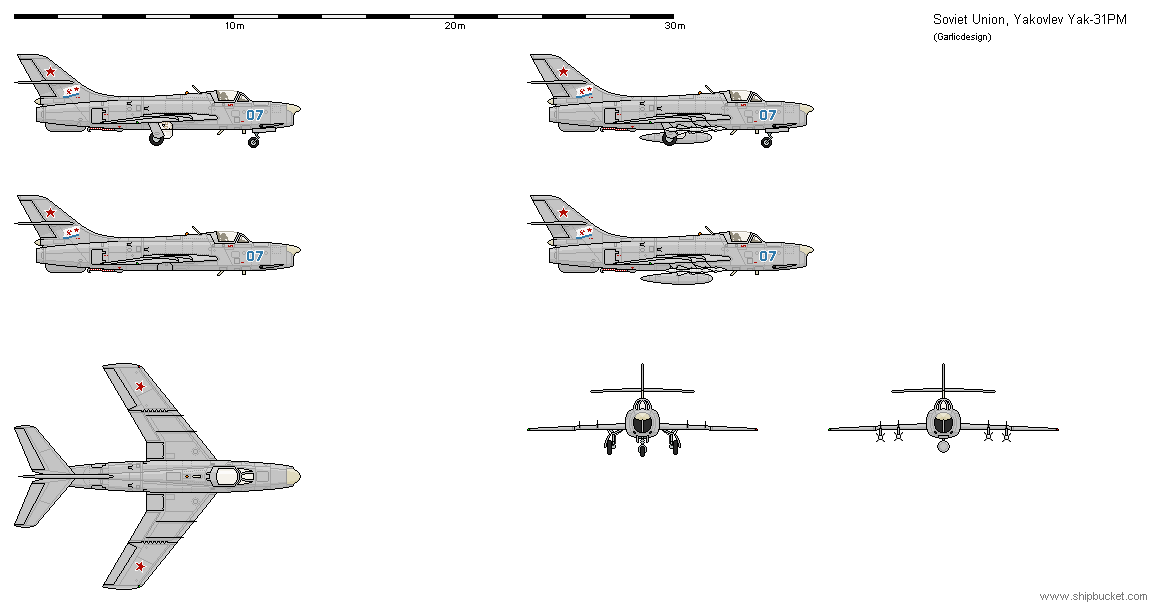

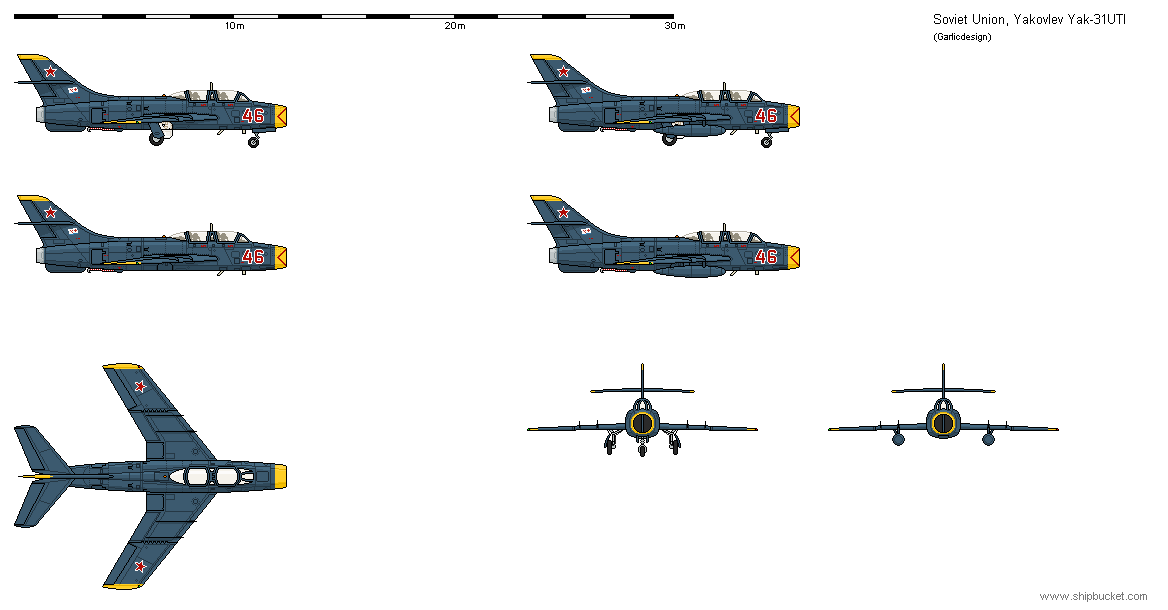

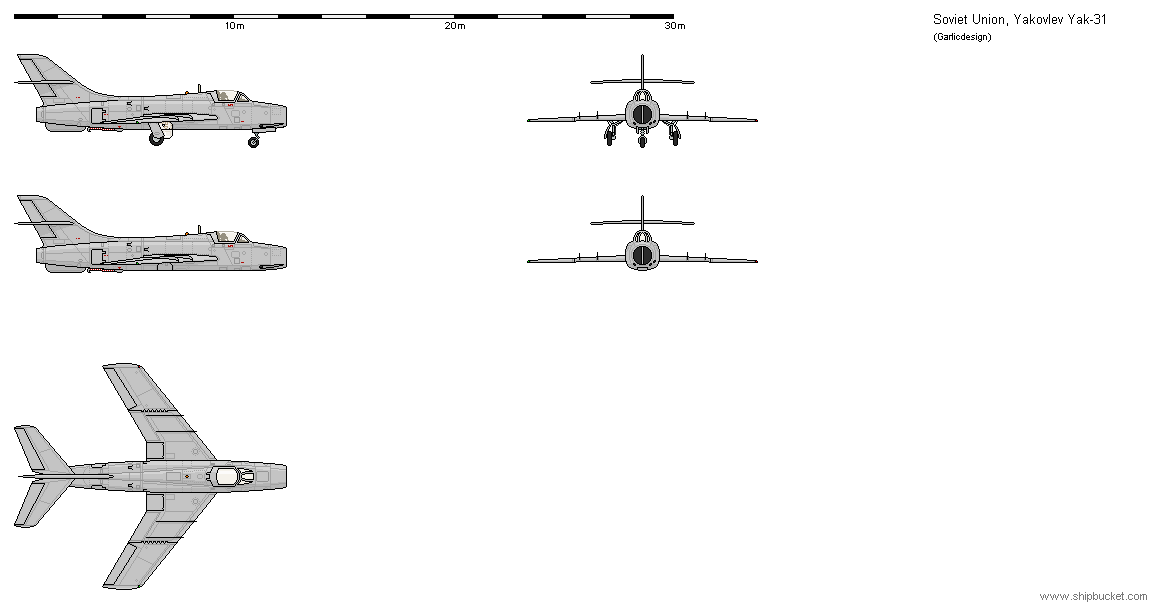

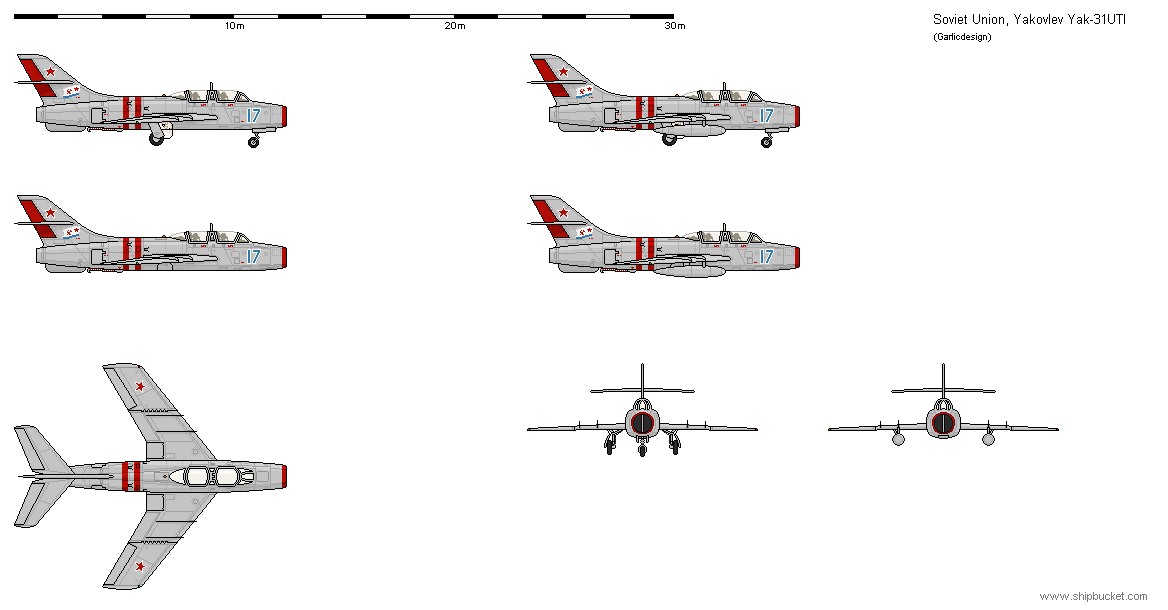

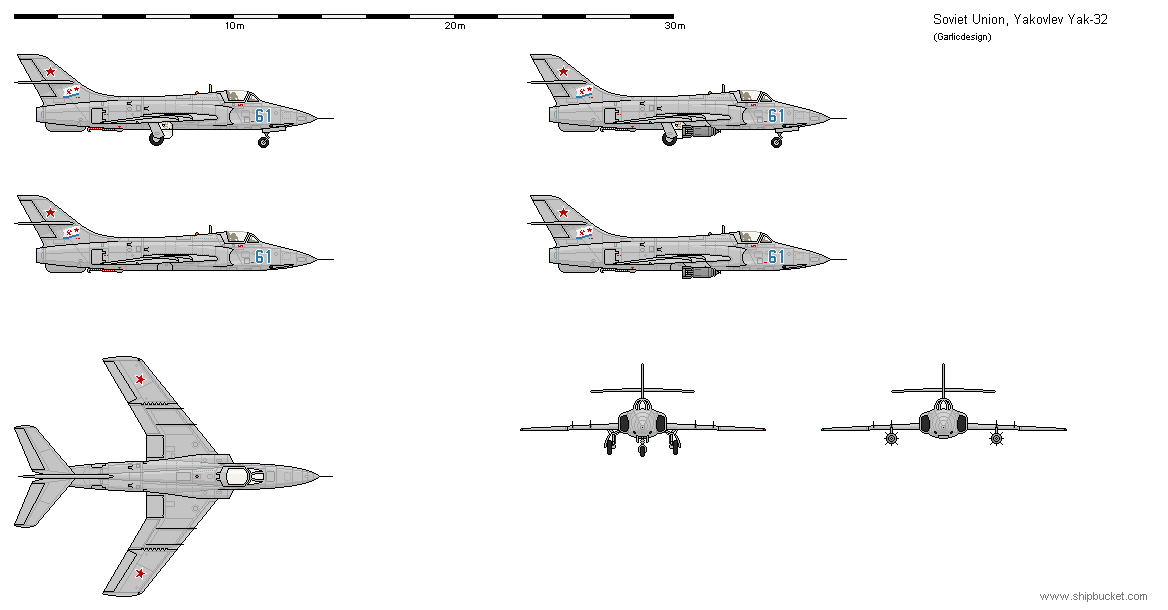

1.3. Yakovlev Yak-31/32 ‘Fenian/Frolic/Mastiff’

For the fighter role of the new Soviet naval aviation, Yakovlev’s proposal beat similar designs by Lavochkin and Mikoyan. The plane received the internal numeral Yak-70 by the Yakovlev OKB. It was a straightforward upscale of the Yak-30 experimental light fighter to the size of the Yak-50 experimental interceptor; externally it resembled the latter more than the former, but retained the conventional tricyclic landing gear of Yak-30 which was expected to offer superior stability for carrier deck operations. Internal structure was strengthened, the landing gear was made sturdier, an arrestor hook was fitted and every inch of the airframe was crammed with fuel tanks to attain maximum range. Being a modification of existing designs, development was quick, and the Yak-70 prototype had its first flight in October 1951. Empty weight was 4.250 kilograms, over a ton more than the land-based Yak-50, and MTOW was a whopping 6.500 kilograms. Armament consisted of three 23mm cannon; there were four underwing hard points, all of which were wet to enable the Yak-70 to maximize its fuel load for long-range maritime missions. Weapons load was set to 1.200 kilograms. Like most Soviet fighters of the age, the Yak-70 was powered by a single Klimov VK-1 turbojet with 27 kN thrust and displayed good agility and pleasant flying characteristics, although it had become a bit too heavy for its somewhat anemic engine, resulting in a rather slow climb and some trouble with catapult shots during trials, including two prototype crashes. The issue could be resolved by fitting an afterburner to the VK-1 in mid-1952, creating the VK-1F which was also installed in the Air Force’s MiG-17, providing 34 kN wet thrust. In this shape, the Yak-70 was approved by the AVMF in 1953 and commissioned as the Yak-31.

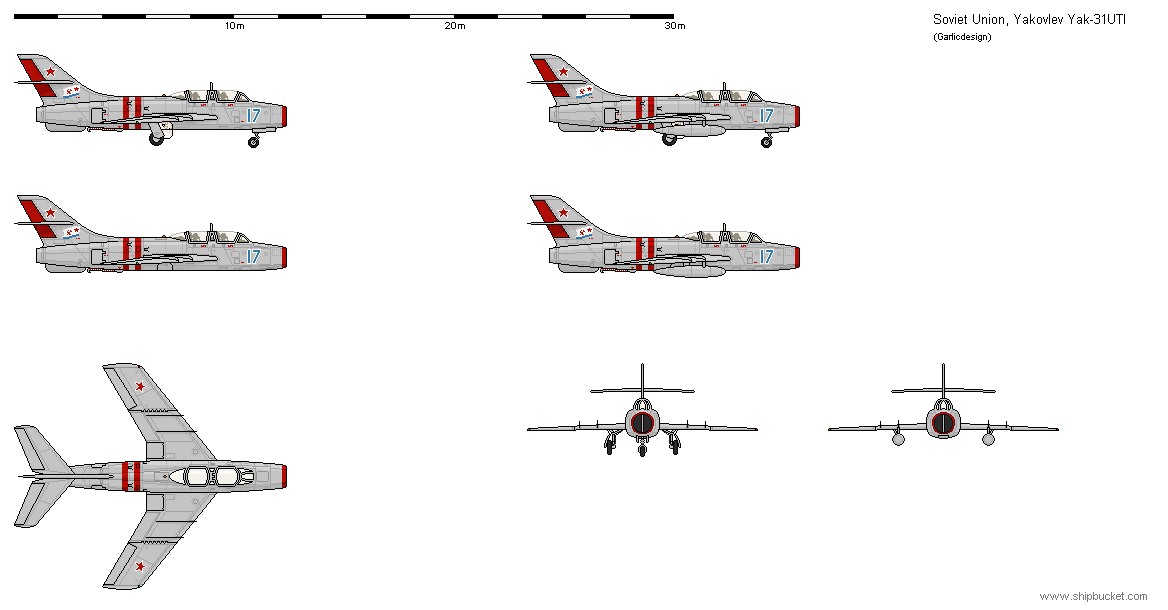

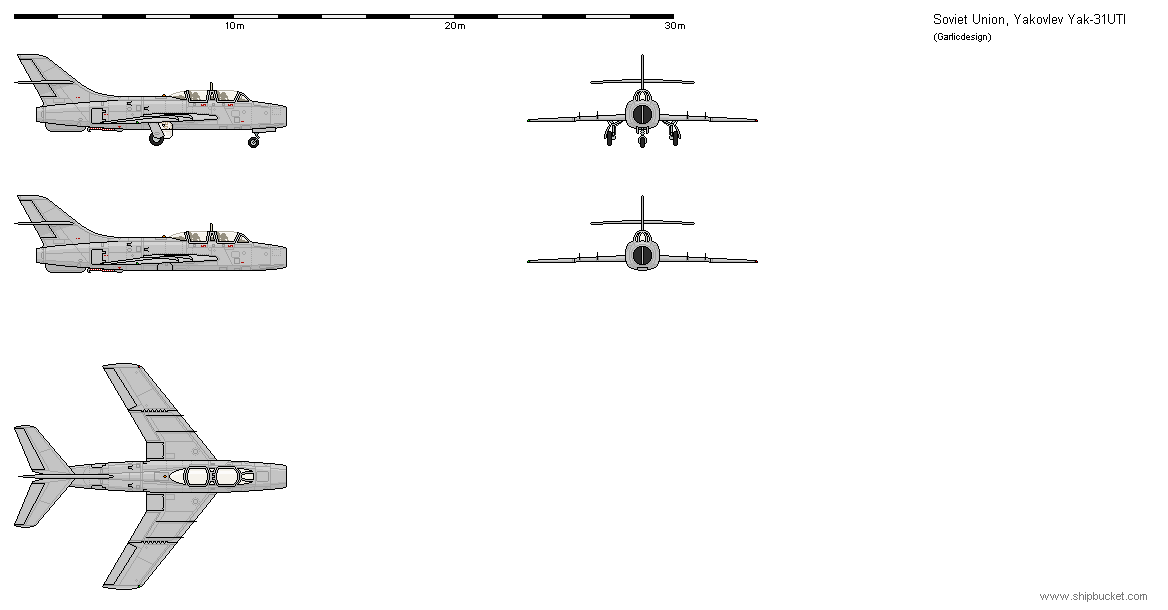

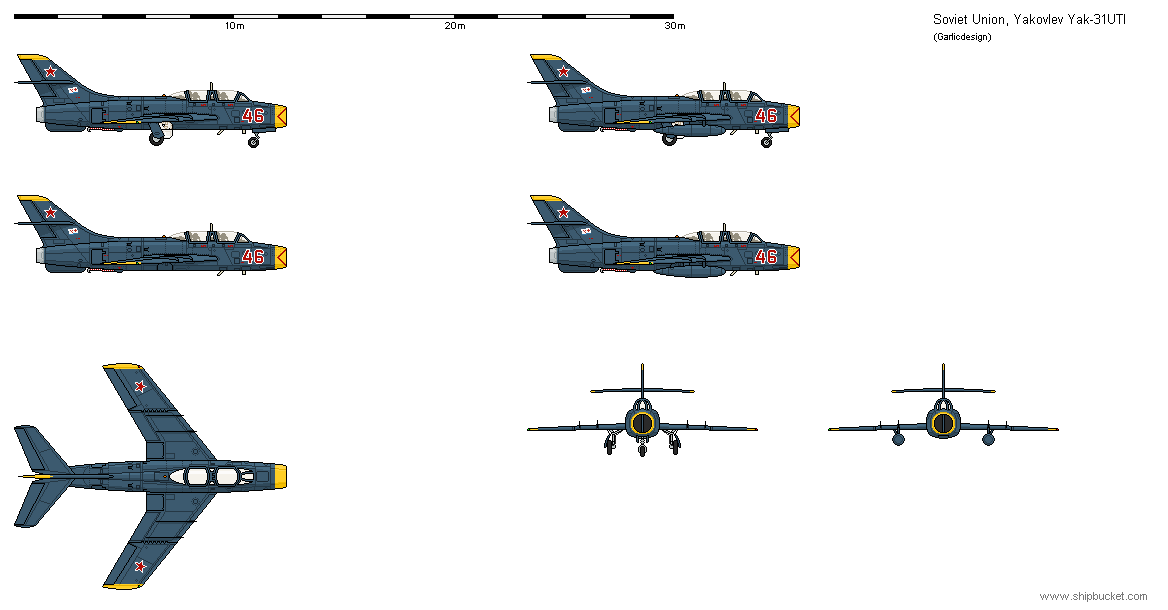

Series production commenced in September 1953, several months after Stalin’s death. A two-seat trainer version Yak-31UTI (up to that time, the Soviet Navy had no jet-qualified pilots) was commissioned early in 1954; initial orders covered 60 fighters and 15 trainers. The trainers had one less 23mm cannon than the fighters and shorter range due to smaller hull fuel tanks. Deliveries were complete in early 1956.

Flight operations aboard Kraznaya Zvezda commenced in May 1955, with a single Yak-31 squadron replacing the ancient La-11s (the Su-6K bombers would remain in service till 1958). By mid-1956, the new carrier Kronshtadt embarked two squadrons of Yak-31s and one of Tu-18s. As the new fighter had first entered service upon an ex-Thiarian carrier, the NATO reporting name pretty much chose itself: Fenian-A.

The operational squadron aboard Kraznaya Zvezda was replaced by a trainer squadron in 1957 in characteristic high visibility markings. The YAK-31UTI was assigned the reporting name Mastiff-A.

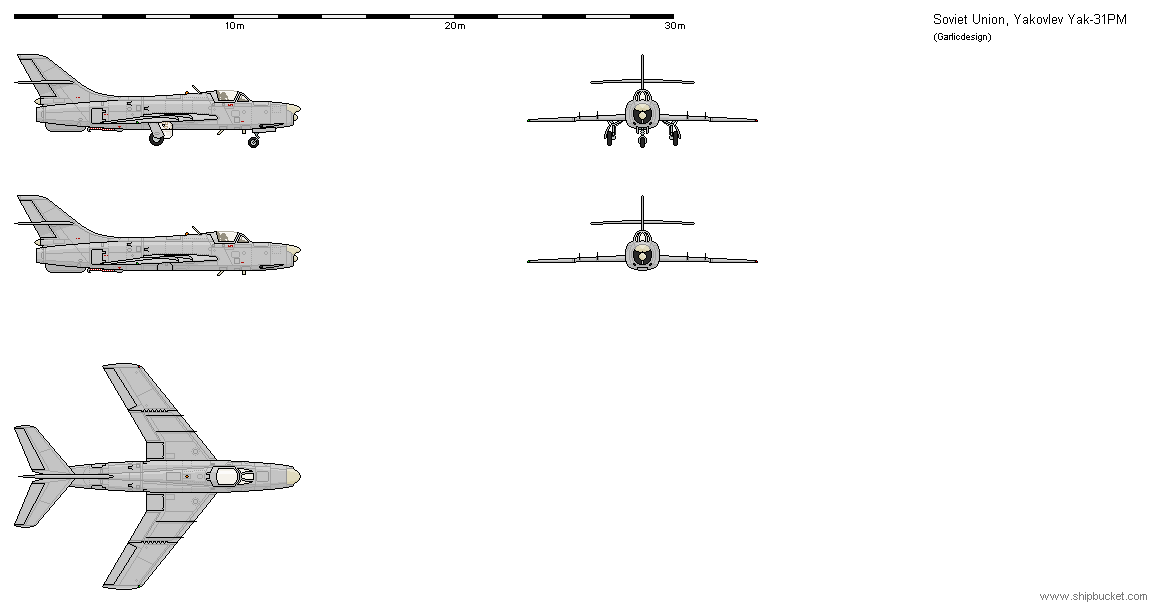

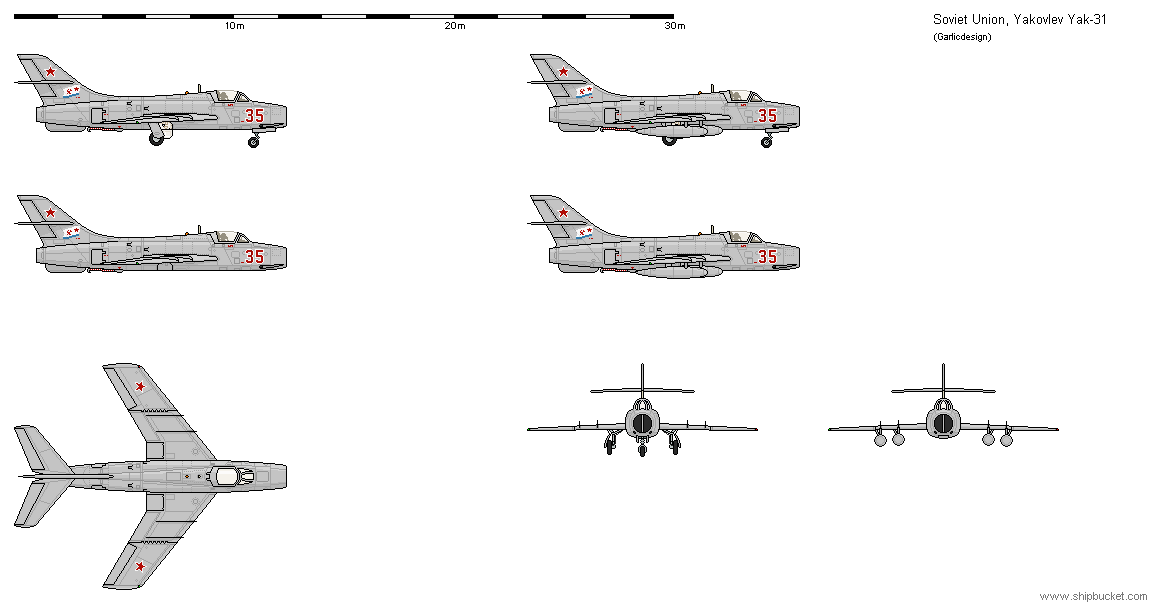

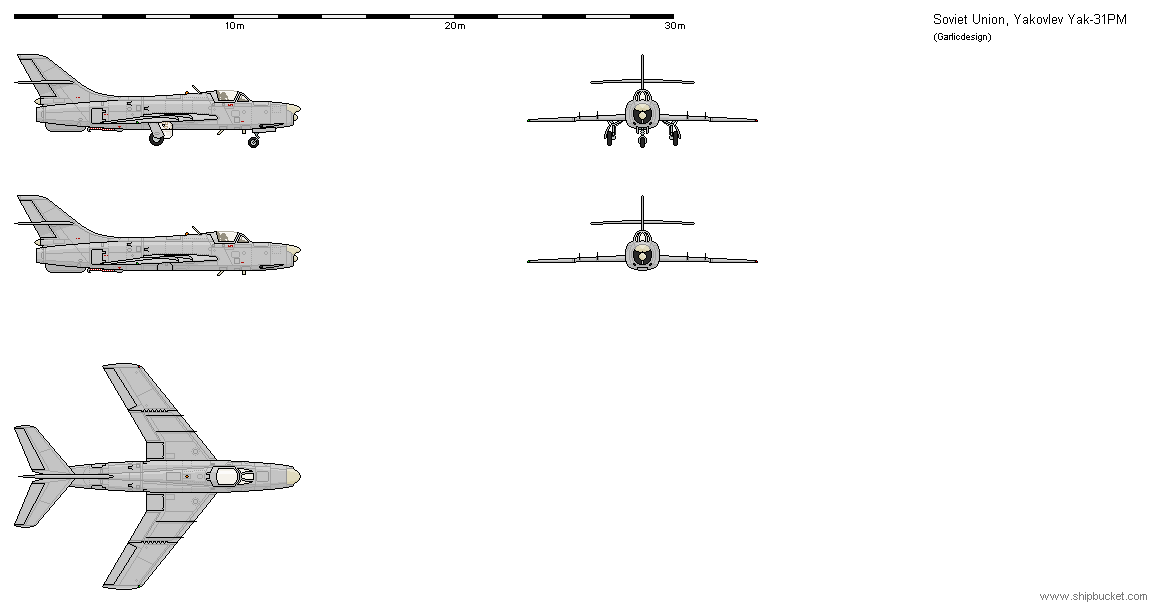

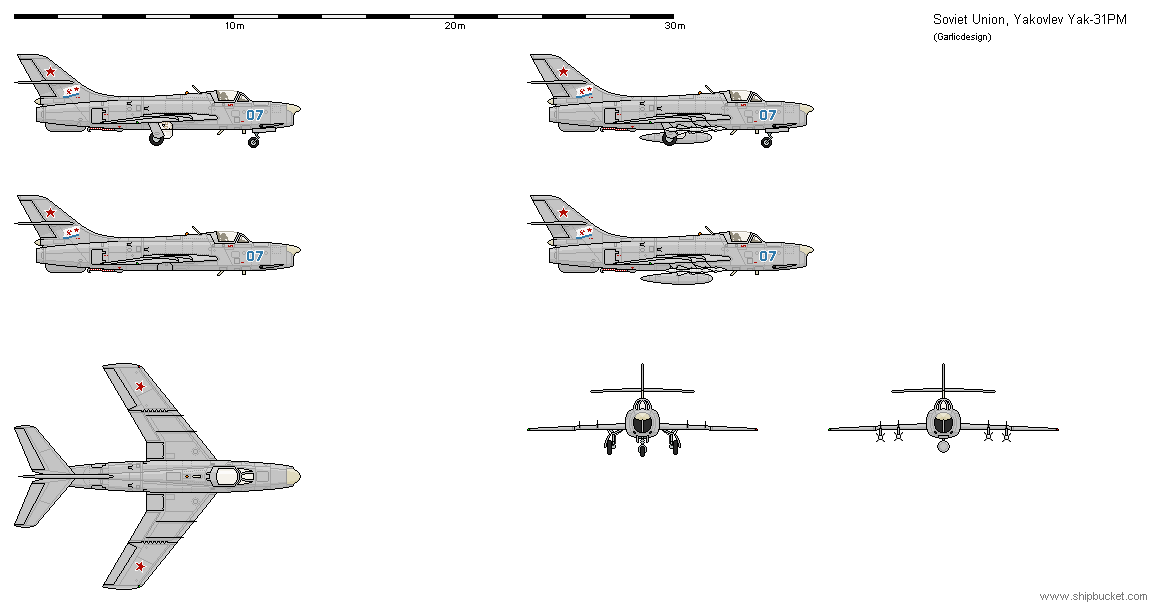

That year, a repeat order for another 60 Yak-31 and 15 Yak-31UTI was issued, because the initial training cycle had resulted in several crashes and other write-offs. Air-to-air missiles had been made available by that time, and it was decided to fit the Yak-31 with a RP-2U Izumrud radar and arm it with two or four K-5 (AA-1) missiles. Unlike other early Soviet missile armed fighters, the Yak-31PM retained two 23mm cannon.

Due to somewhat higher weight, performance suffered a little, and as all hard points were now occupied with missiles, range suffered a little more. The added all-weather performance however was considered worth the trade-offs. All 60 machines of the repeat order were delivered as Yak-31PM, while the trainers were identical to the basic Yak-31UTI. Deliveries were complete by mid-1958. The Yak-31PM was designated Fenian-B by NATO.

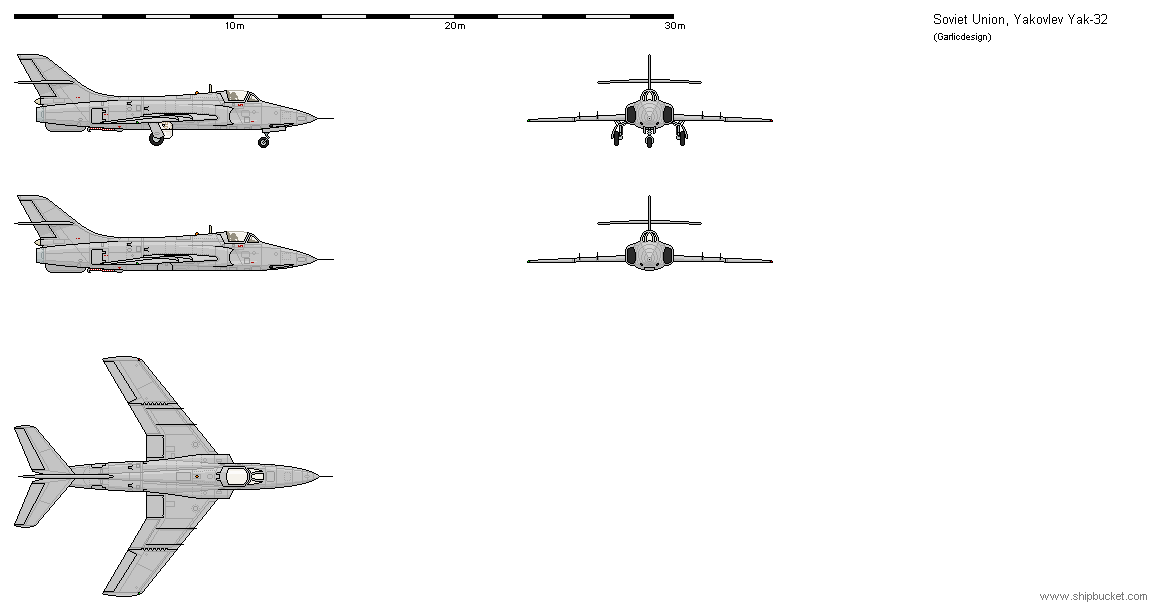

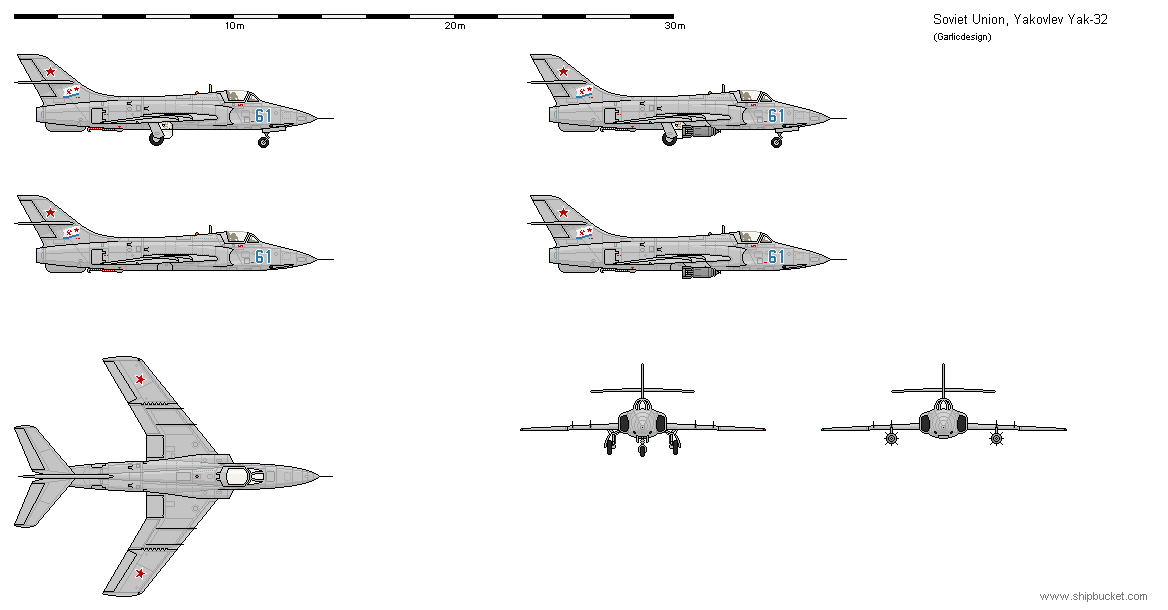

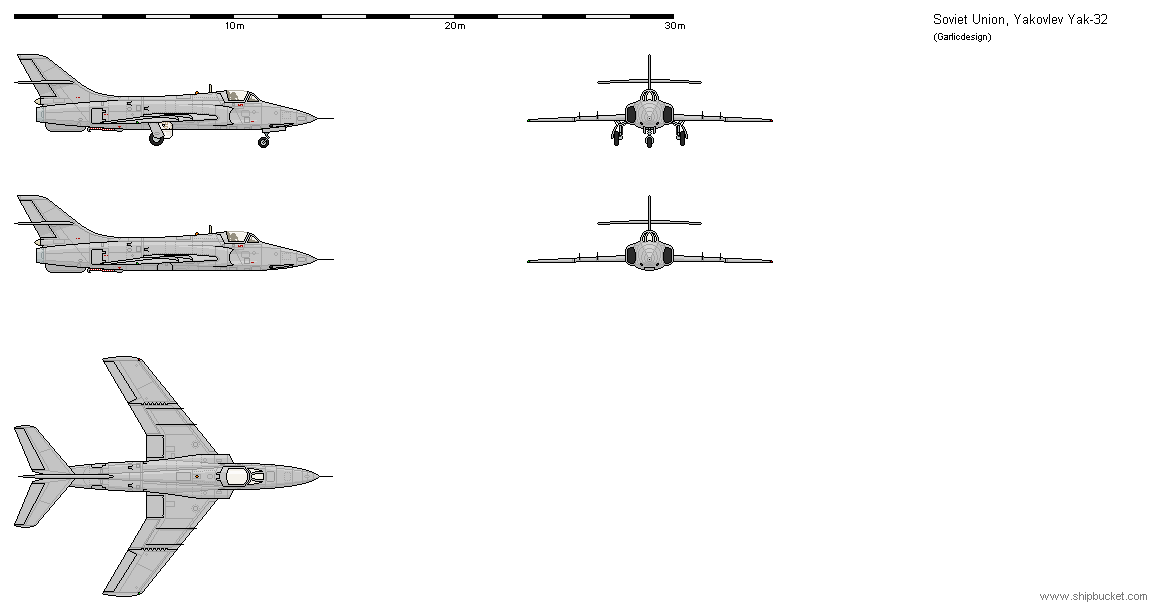

By that time, the AVMF had decided to add strike power to its carrier force and embark a fourth squadron by introducing permanent deck parking. The standard Yak-31 was no great attack plane and needed tob e heavily modified. To attain the necessary range for antiship strike missions, Yak-31s forward hull needed to be reshaped; all electronic gear was relocated into the forward hull, which received a pointed cone, and the air intakes were relocated to the wing roots. This allowed for additional fuel tanks in the hull behind the cockpit for a 30% increase in range over the Yak-31MP. Weapons load increased to 2.000 kg (not counting two 23mm cannon and their ammunition) and MTOW to 7.500 kg. The higher weight was offset by installing a newer Tumansky RD-9BF powerplant of 29 kN dry thrust, with 37 kN on reheat; improved aerodynamics of the new nose also helped to retain the same flight performance as the original Yak-31. The revised design (named Yak-75 by the OKB) differed sufficiently to warrant a new official designator too; in keeping with assigning even numbers to strike aircraft, this variant was commissioned as the Yak-32 in 1960.

60 machines were produced till late 1961, plus another ten standard Yak-31UTI trainers. The Yak-32 also received a new NATO reporting name; unlike the basic version, this time it was randomly assigned: Frolic-A.

Although by then enough planes to equip them were available, the two additional carriers planned for 1955 never materialized. Those Yak-31s not needed for shipboard operations were employed as fighter cover for Soviet naval bases in the arctic; although jet fighter development in the second half of the 1950s rendered them rapidly obsolescent, Khrushchev approved no replacement prior to the sobering experience of the cuban missile crisis in 1961, which sparked further carrier construction (see 1960s below). In order to prepare the AVMF for this surge in size, another thirty Yak-31UTI were built in 1961/2, plus a repeat order for 40 Yak-32 and 40 Yak-31PM, which were fitted with the DR-9BF engine of the Yak-32. They were dubbed Yak-31PFM upon completion (NATO reporting name Fenian-C). Although the type was clearly obsolescent, it was all that was available at the time. A final lot of 50 Yak-31UTI was added in 1964/5. Including prototypes, production totaled 392, of which 120 were trainers.

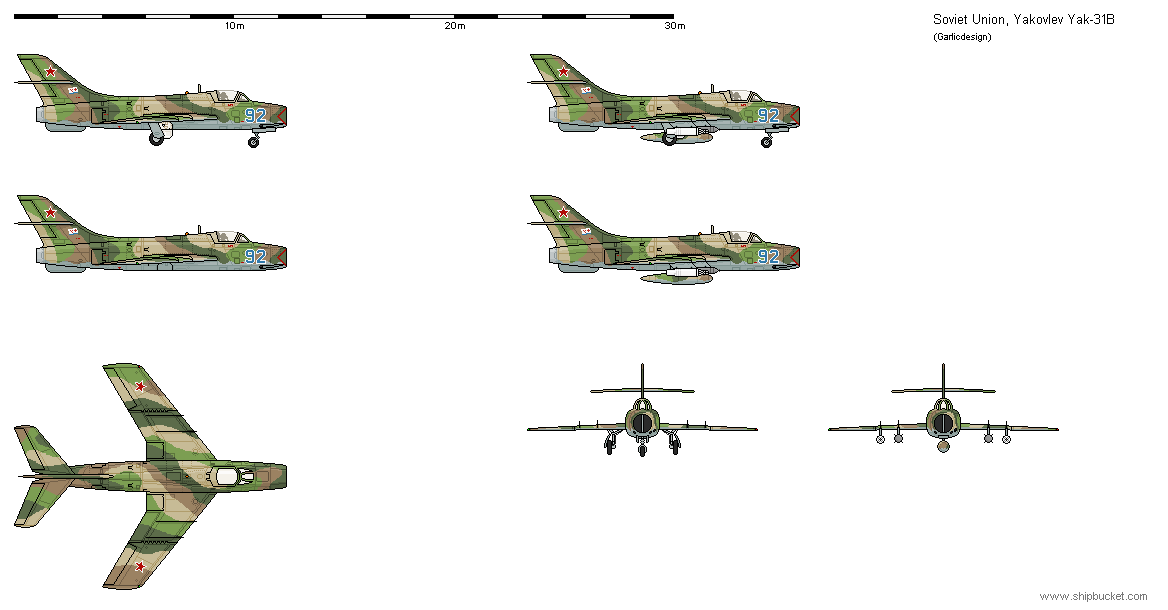

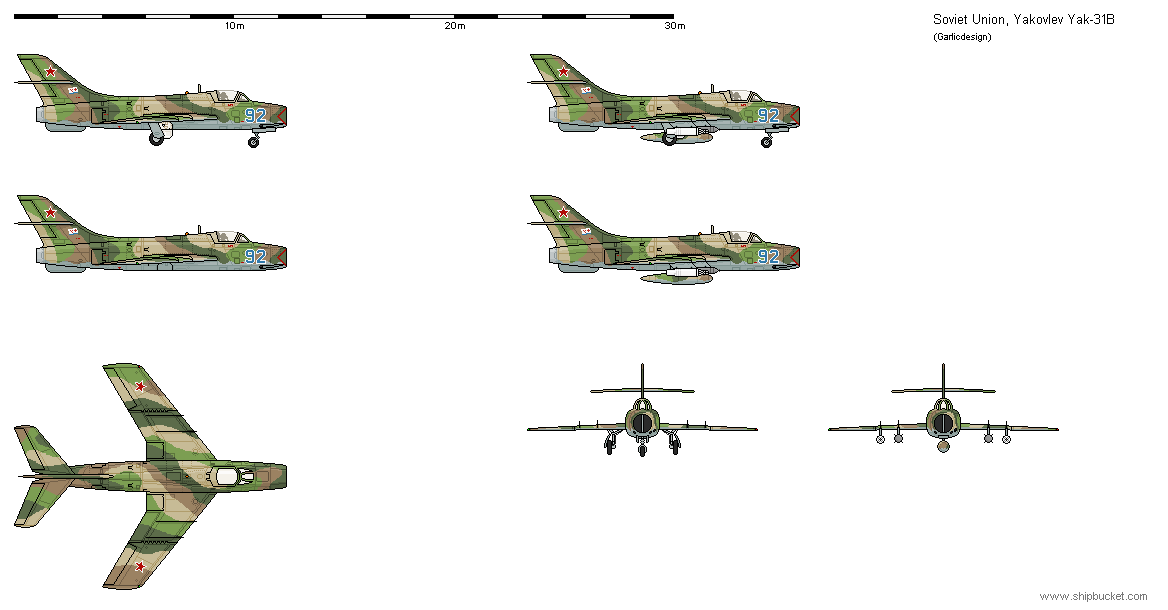

As development of the ambitious replacement project Yak-33/34 dragged on longer than expected, the Yak-31/32 soldiered on throughout most of the 1960s. Some 30 remaining original Yak-31s were relegated to the land-based strike role in 1961 and based on the Crimea. They received a four-colour camouflage paintjob, and arrestor hooks and catapult fittings were removed. They were only capable of employing dumb bombs and unguided rockets; their designation was now Yak-31B and their reporting name changed to Fenian-D. The last of them were de-commissioned in 1968.

The Yak-31PM were refitted to carry the new K-13 (AA-2) air-to-air missile (both in IR and SARH mode) in 1962/3; the Yak-31PFM carried it from the start, just like the RWR, which was retrofitted to the Yak-31PM (new NATO reporting name Fenian-E). When commissioned in 1964, the Yak-31PFM were the first Soviet naval aircraft to receive the new blue paintjob with green anti-corrosive paint on the underside, which was to remain standard for a quarter century. Although the most mature version oft he Yak-31, the PFM had the shortest career, because they were supplanted by the brand-new Yak-33 starting in 1966; the last Yak-31PM retired in 1967, and the last Yak-31PFM in 1969. As the latter were still rather new, 25 hulls were rebuilt to Yak-31UTI trainers. All others were either displayed or scrapped.

The Yak-32 needed to stay in service even longer, because full development of the Yak-34 strike fighter took till 1971, and the latter aircraft’s size prompted development of a smaller strike fighter (the Yak-39) which would not become available before 1976. The Yak-32s were adapted to fire Kh-66 (AS-7) missiles in 1968, also receiving a RWR, a navigation radar, a targeting system for the AS-7 and two more hard points under the air intakes (Yak-32M, reporting name Frolic-B). By 1970, all three Soviet carriers (Kronshtadt, Moskva and Leningrad) had one squadron of 18 Yak-32s embarked (12 on Kronshtadt); the new Pr.1153 Kiev-class carriers were equipped with Yak-34s from the start. Replacement oft he Yak-32 with Yak-39 commenced in 1976 and was complete in 1979.

The Yak-31UTI had the longest career, remaining AVMF’s prime advanced trainer for carrier operations until well into the 1980s; mostly operating from Kronshtadt, which was relegated to the training role in 1975 when Kraznaya Zvezda was scrapped. A hundred were available in 1970 (including 25 rebuilt Yak-31PFMs), and they were not entirely replaced before 1985, when enough Yak-39UTIs for carrier training ops were available.

Although produced in tiny numbers by Soviet standards and never exported, the Yak-31/32 family was invaluable to gather the kind of experience in carrier aviation that was necessary to establish the Soviet Navy as a true blue water force.

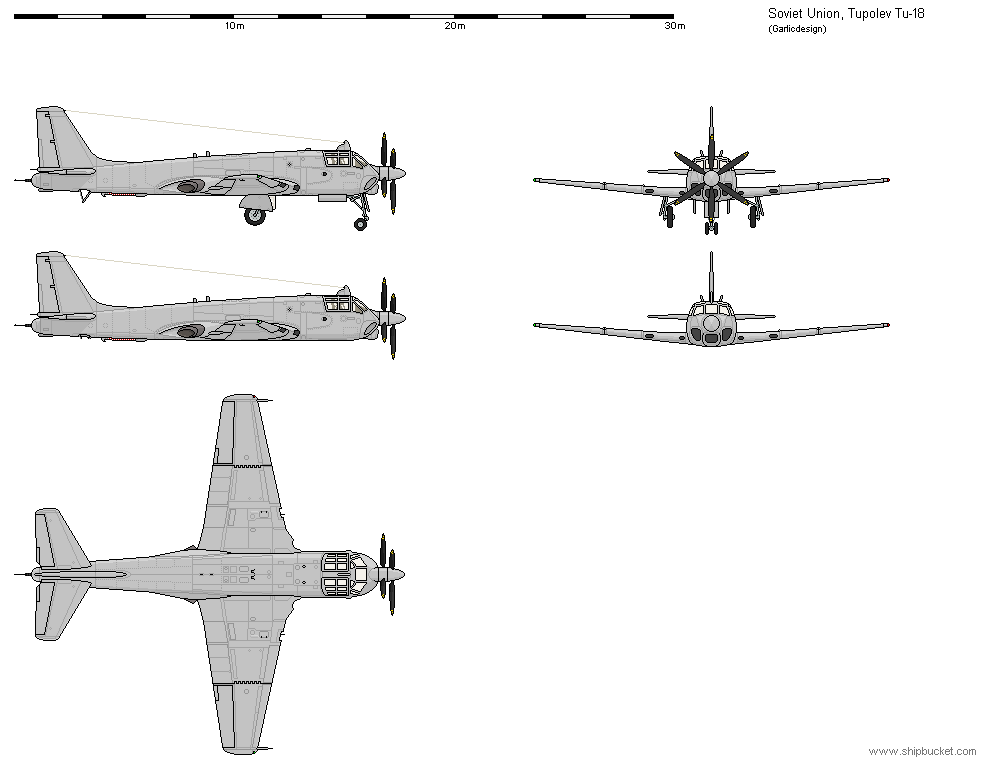

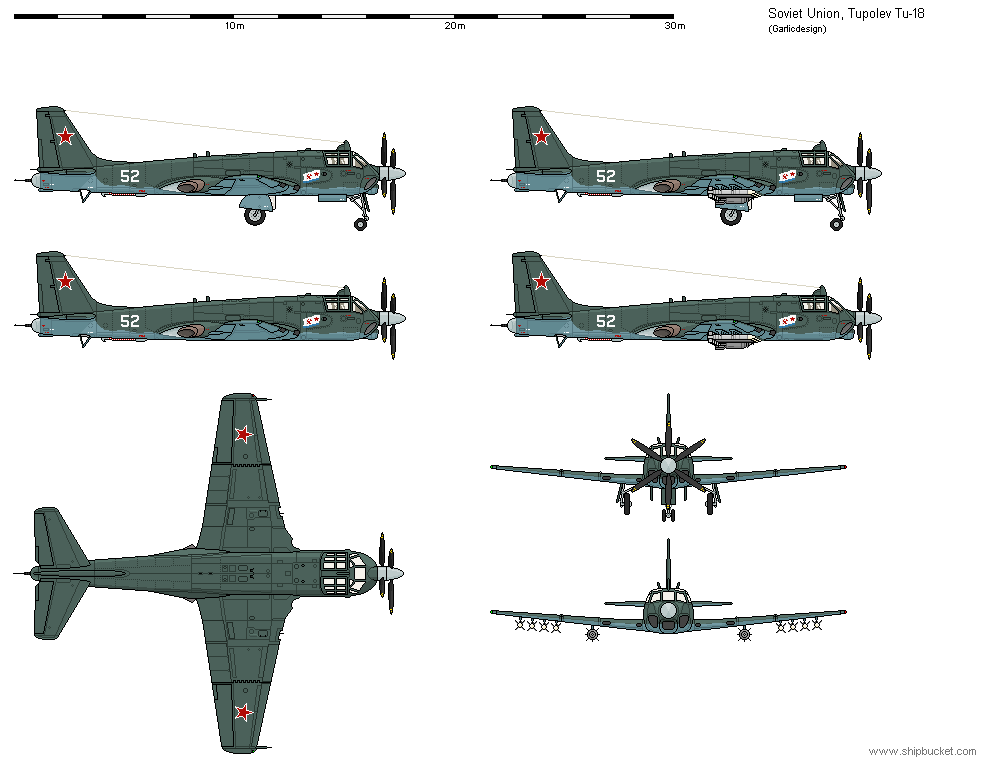

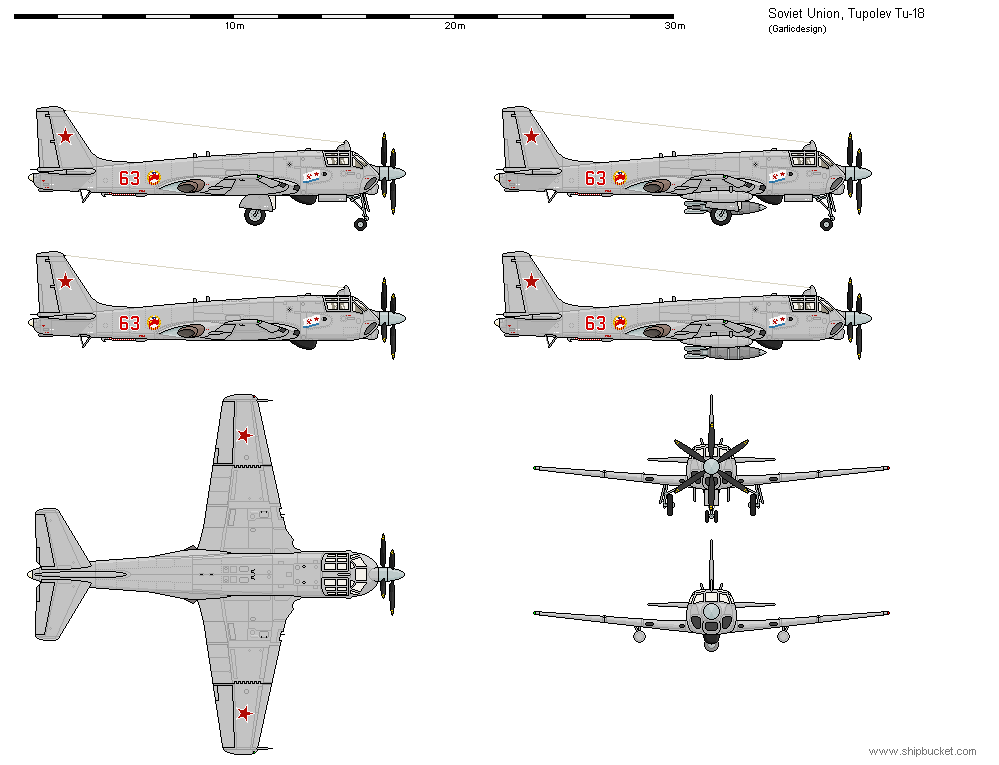

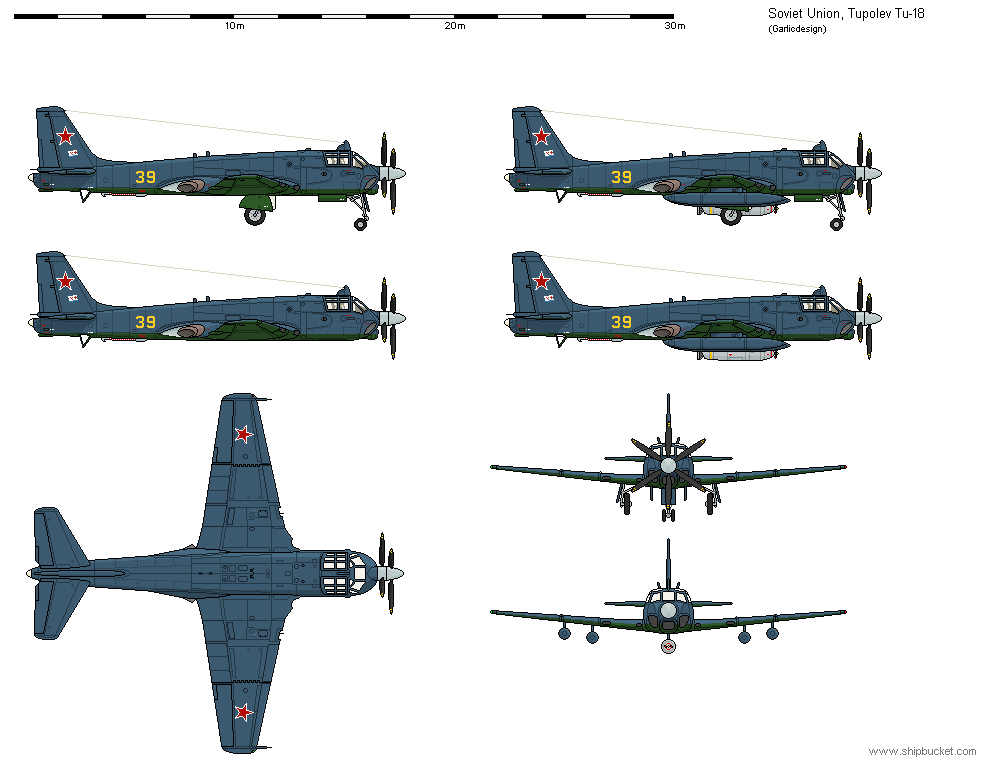

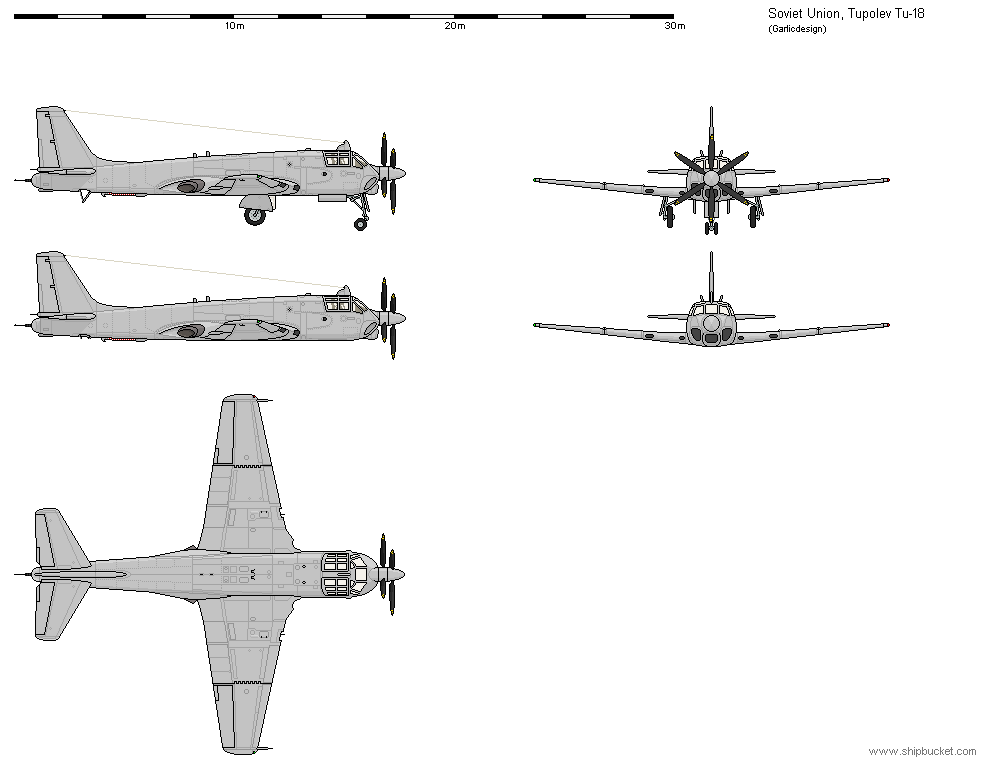

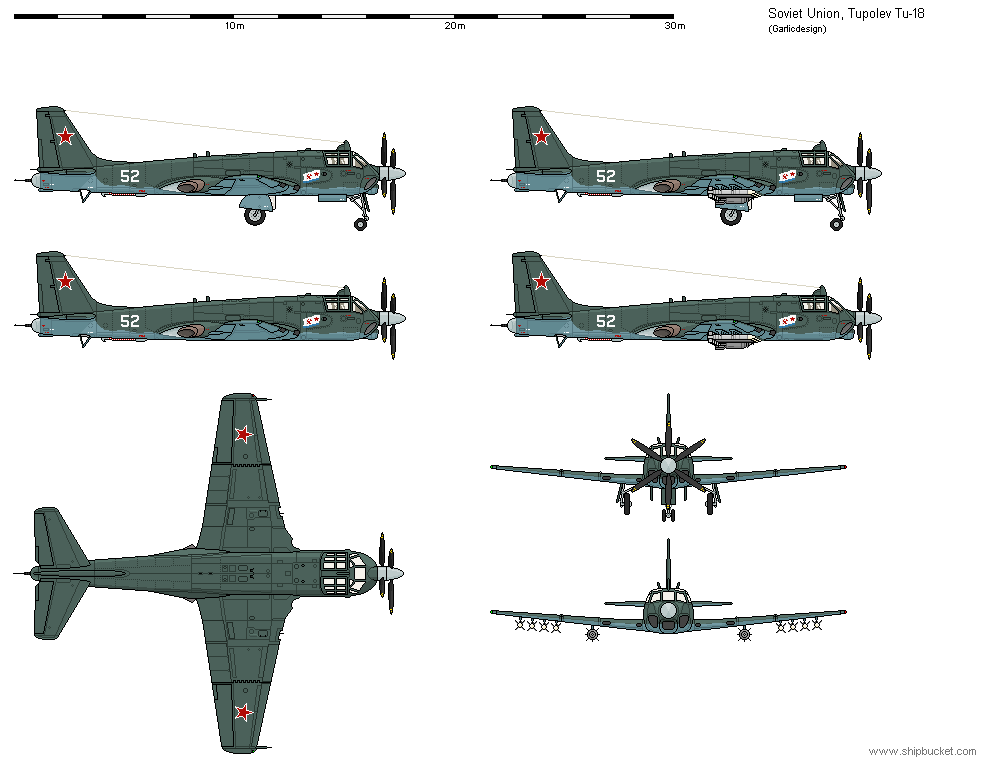

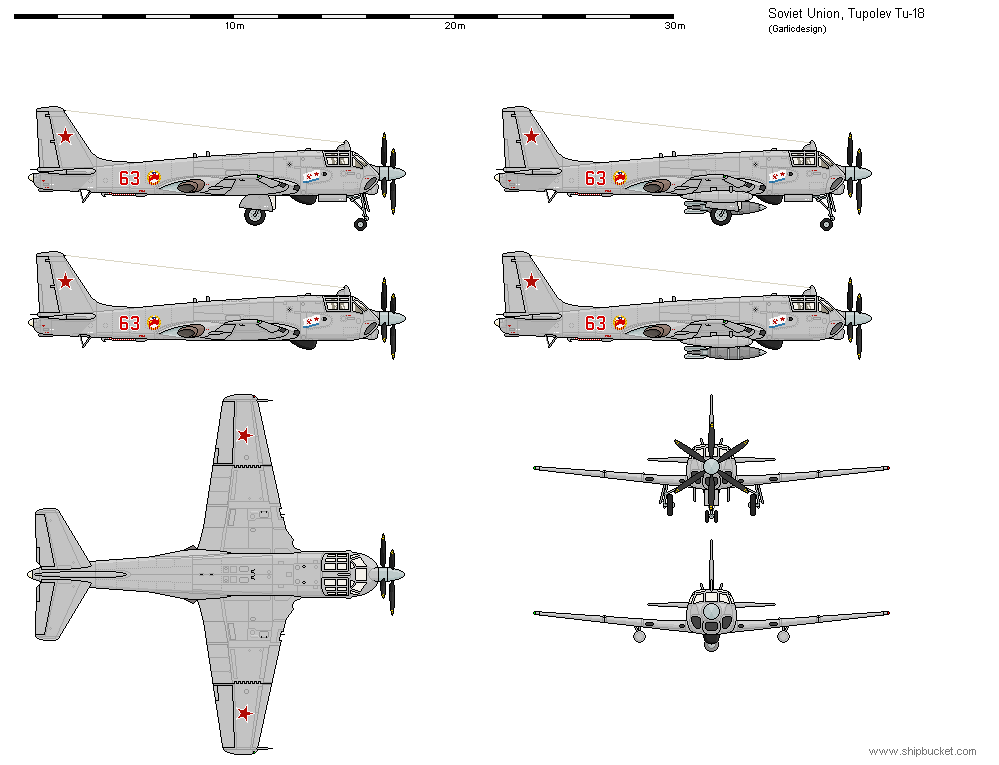

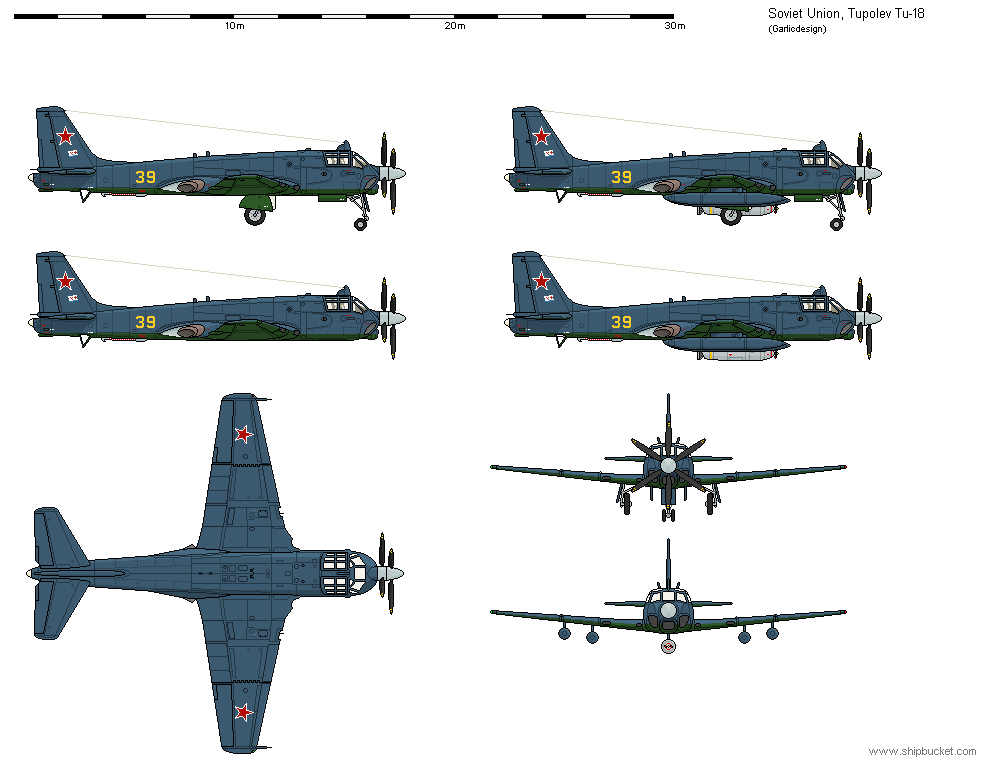

1.4. Tupolev Tu-18 ‘Boot’

Development of a specialized carrierborne strike aircraft commenced in 1949 on Stalin’s orders. Tupolev chose a single-engined turboprop-powered approach, utilizing the new Kuznetsov TV-2M turboprop developing 7.650 shp. The attempt to attain optimal visibility for the two-man crew resulted in a side-by-side cockpit arrangement at the extreme forward end of the fuselage, only a meter behind the six-bladed contra-rotating propeller. They were armed with two 23mm cannon in the wings for strafing and another two in an automatic radar-guided tail turret for self defence. The airplane, dubbed Tu-91 by the Tupolev OKB, could only be described as extremely ugly.

Nevertheless, when it first flew in 1954, performance was convincing. The prototype met the speed requirement of 800 kph and exceeded the payload requirement of 1.500 kg more than twice over; in service, the type was cleared for 3.200 kilograms. Range was excellent due to the economic turboprop propulsion and the large internal fuel supply; with 2.000 kilograms of payload, a combat radius of 1.000 km was attained. The hull was robust, maintenance requirements were moderate despite the somewhat experimental engine, and flight characteristics were pleasant. Although Khrushchev himself ridiculed the Tu-91s looks, he approved a limited production run of 75 machines to equip two carrier-based squadrons and an OCU of nine each, and two land-based squadrons of twelve each, plus attrition replacements. The planes received the service designation Tu-18 and the NATO reporting name Boot. The first squadron was commissioned in 1957 and embarked on the brand-new carrier Kronshtadt. Unlike contemporary jets, which were painted silver, they still carried the AV-MF’s WWII-vintage blue-grey livery. Typical armament would comprise two 500 kg bombs and eight big 240mm rockets.

By 1959, all 75 Tu-18 were in service; one squadron each was based on Kronshtadt and Kraznaya Zvezda, and the land-based units were based in the Far East. In 1960, the type was cleared for AN-28 nuclear gravity bombs, and in 1962, radar was retrofitted in ventral pods behind the bow wheel well. The automatically fired self-defense cannon aft, which never worked satisfactorily, were removed during this refit.

Despite its initially good performance, the Tu-18 did not age well. Their radars did not work because of interference from the contra-rotating propellers, and their speed was thoroughly unimpressive by 1960s standards. Integration of more modern weapons proved impossible, and the type’s prominent size limited air group strength on the smallish Soviet carriers. Nevertheless, the Tu-18 was kept in service till 1973 as the fleet’s dedicated nuclear weapons carrier. As antisubmarine patrol aircraft (although ill-equipped for this task) and tankers, they lingered till 1985.

They were replaced in the bomber role by the Yak-34 from 1971 and in their other tasks by the Tu-24, which had been developed from Tu-18s airframe, from 1976.

2. The 1960s

Khrushchev was never happy with having to spend money on anything but big nukes and in 1960 announced to de-commission the carriers by 1961 at latest, after only five years of operations. But during the Cuban missile crisis of 1961, Kronshtadt suddenly found herself at the center of a Soviet task force also containing the ex-Thiarian battlecruiser Arkhangelsk (ex-Caithreim) headed for the central Atlantic. The Russian naval aviators achieved nothing, facing five US carrier battlegroups outnumbering them 15:1 in aircraft, but proved that they had mastered carrier operations. With Khrushchev’s authority somewhat shattered by the outcome of the Cuban crisis, Admiral Gorshkov managed to prevail on the Supreme Soviet to approve construction of two carriers to an all new design code-named PBIA in 1961, and to order development of a replacement for the Yak-31/32 for deployment in 1965 at the latest. PBIA was originally to be nuclear-powered, but rather small; the final design had a conventional steam plant and was somewhat larger, becoming the Moskva-class, commissioned in 1967 and 1969.

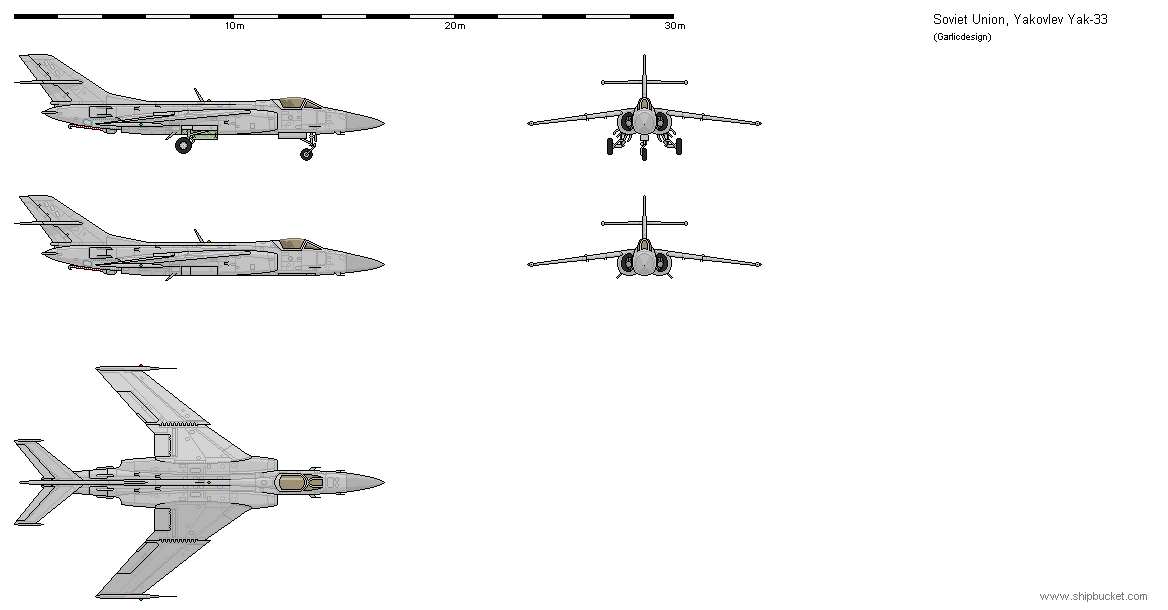

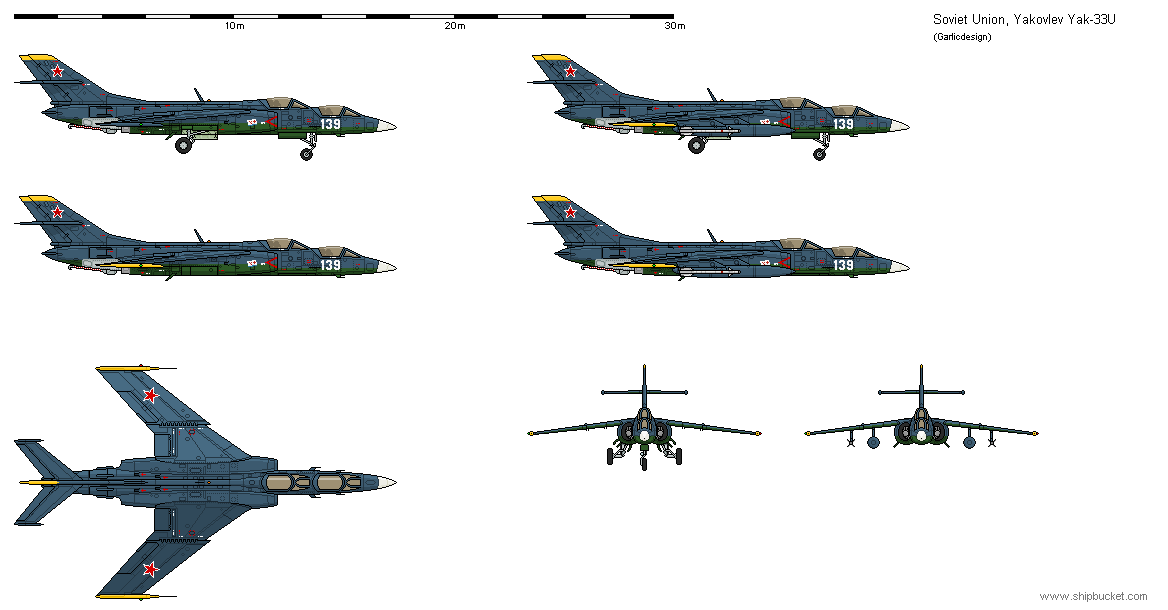

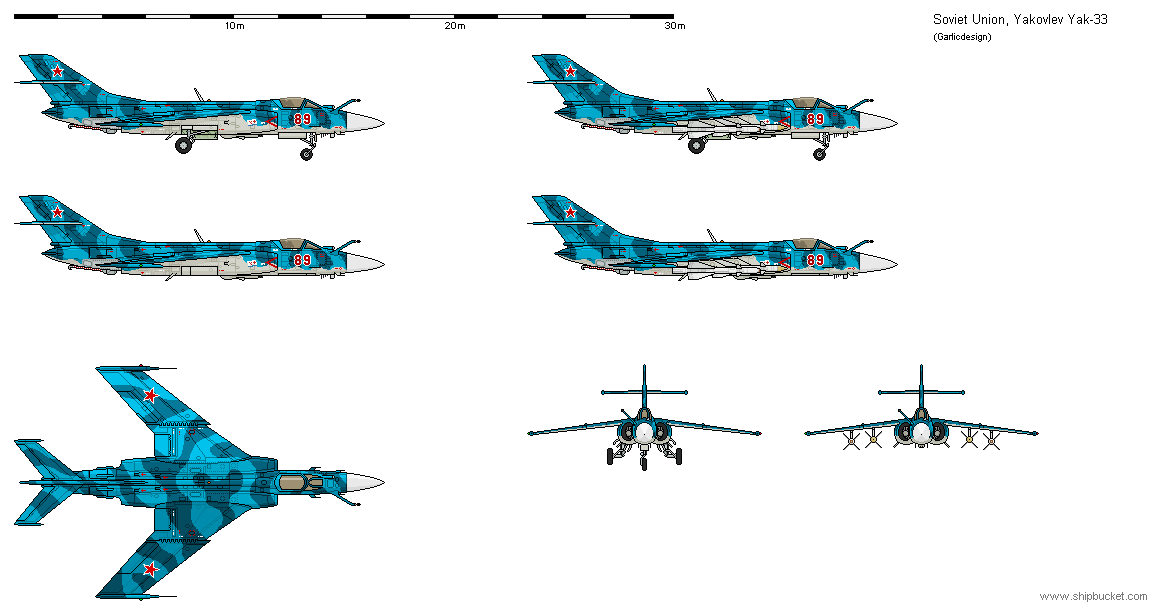

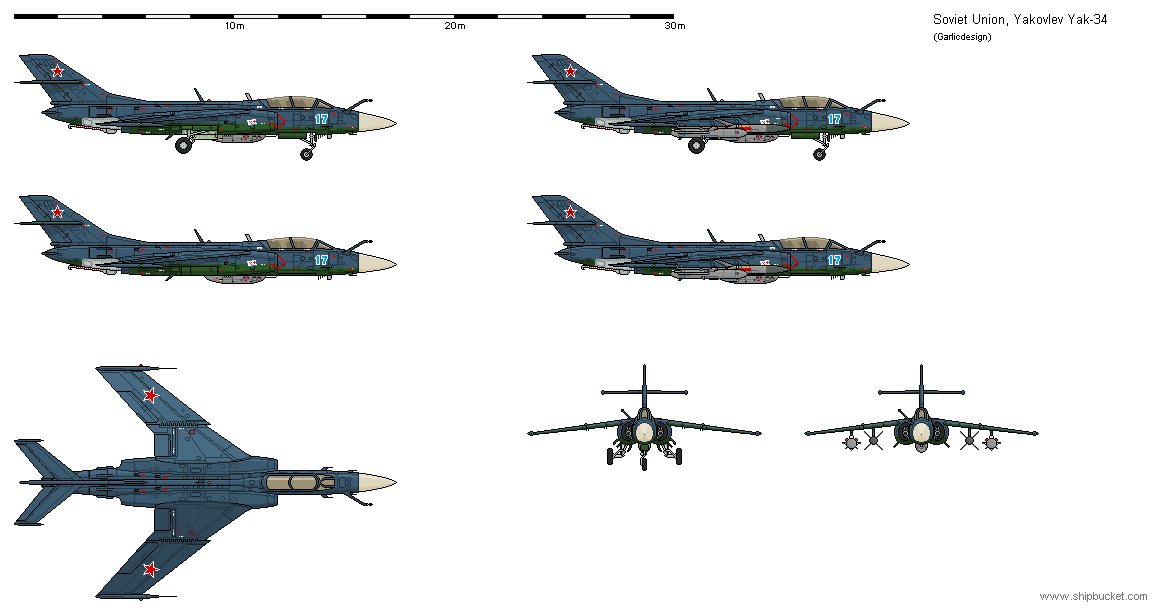

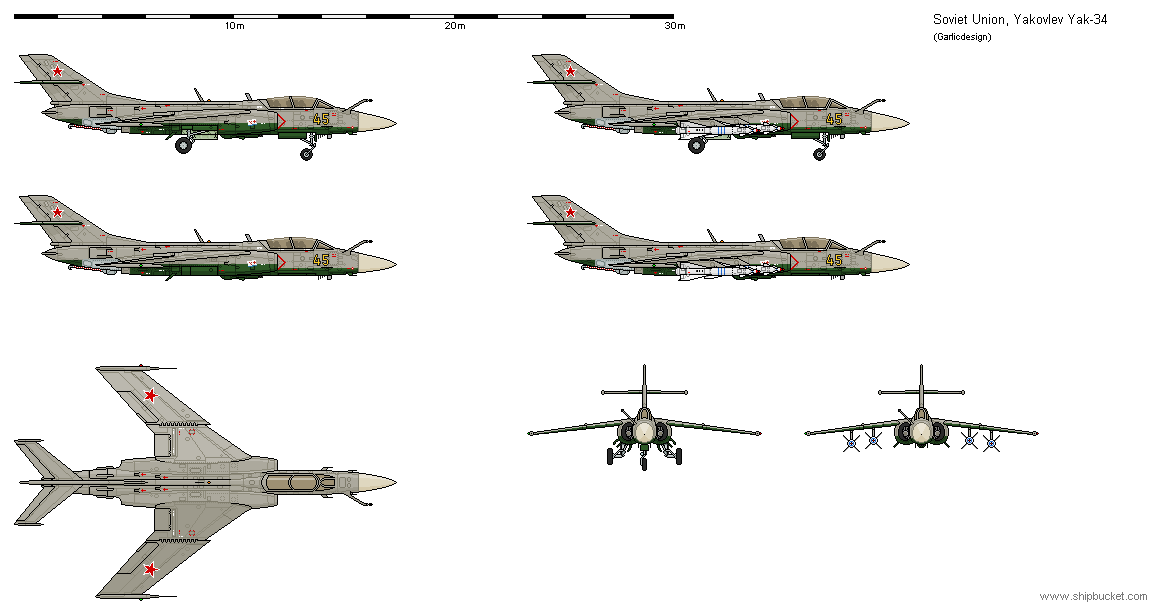

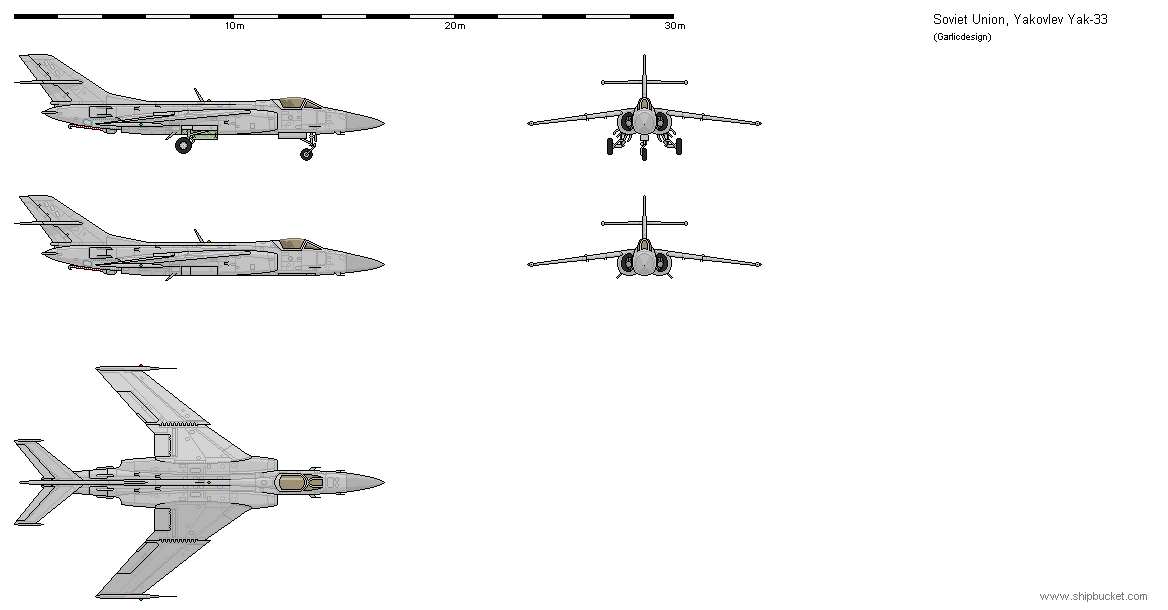

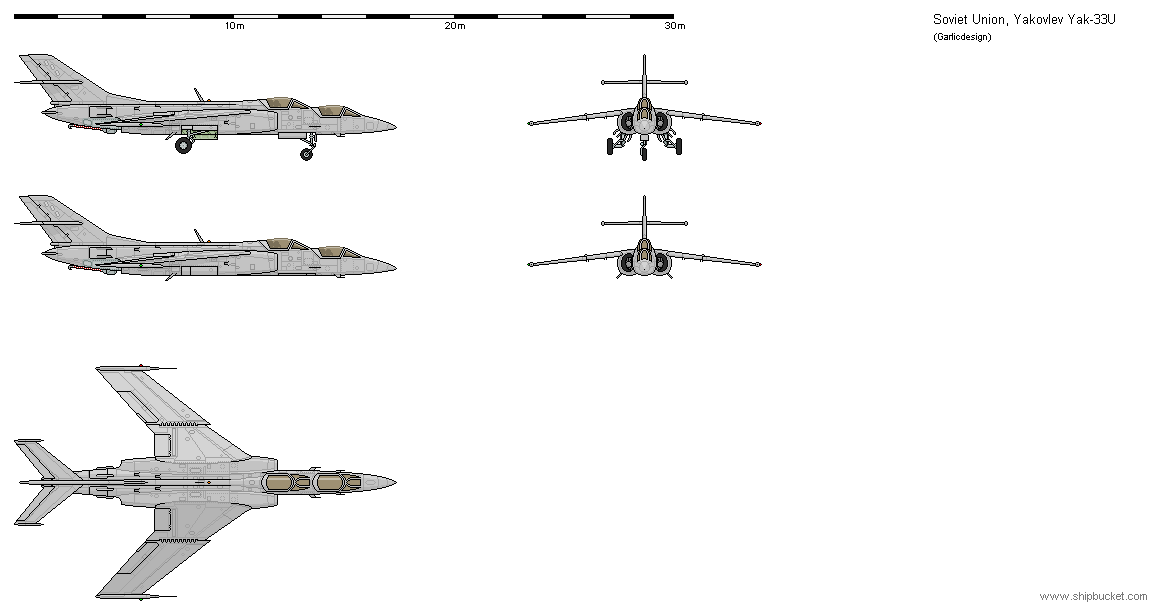

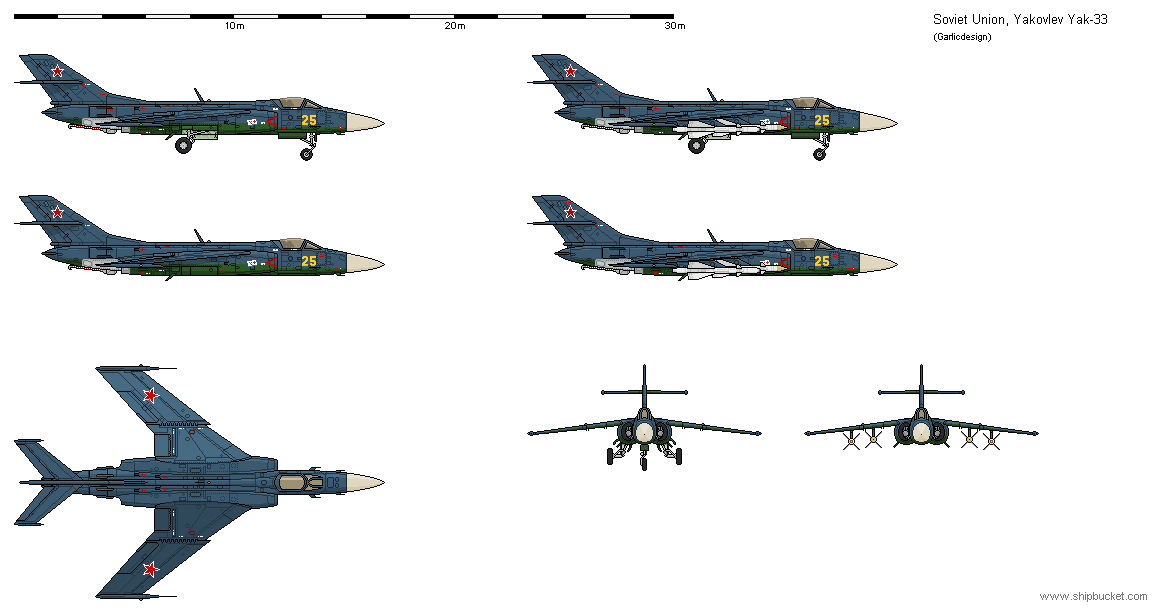

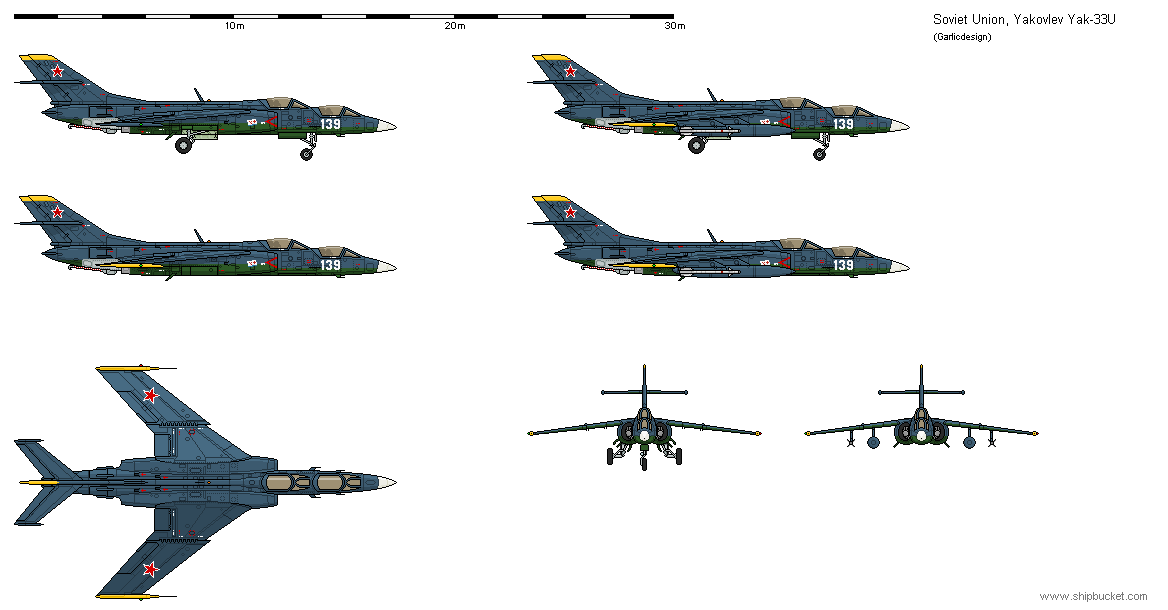

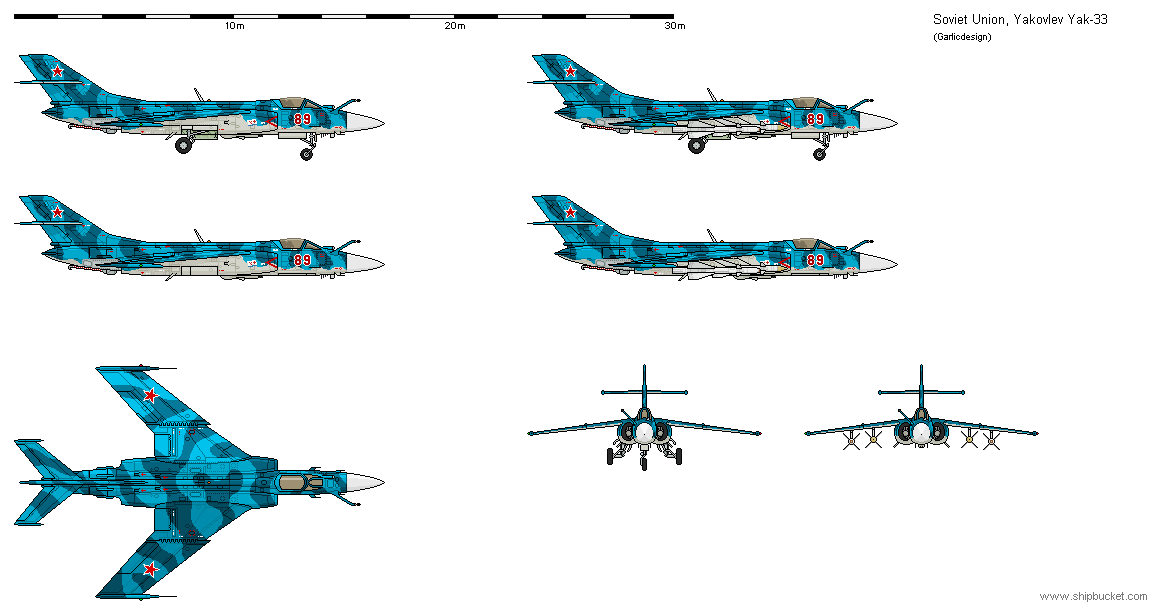

2.1. Yakovlev Yak-33/34 ‘Falchion/Brawler/Minion’

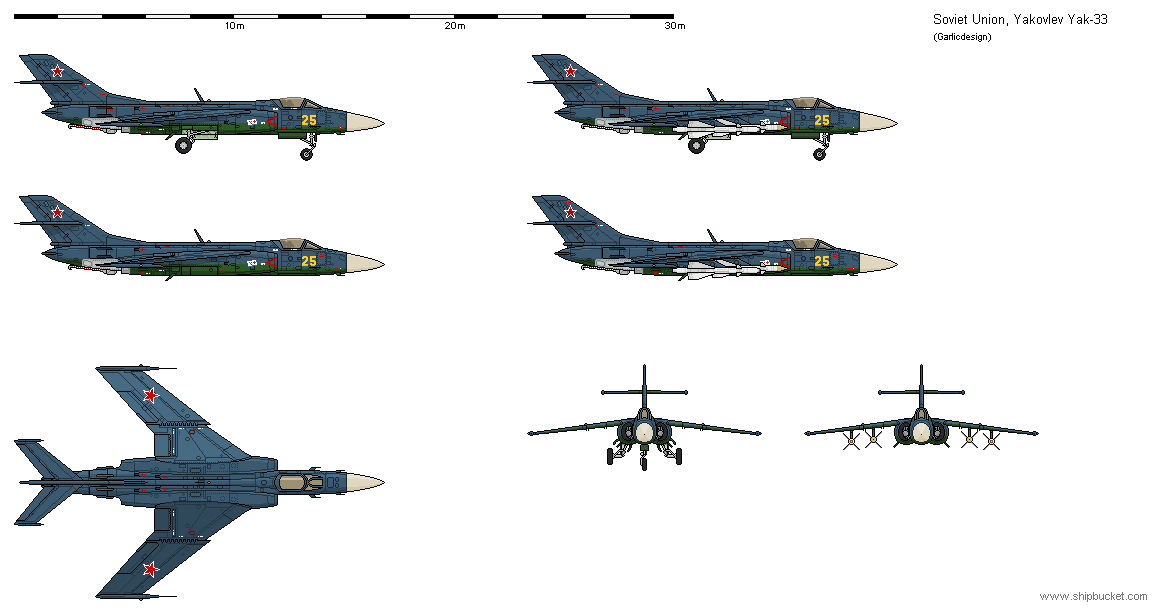

Although the Yak-31 had been a satisfactory little plane, it was a far cry performance-wise from its western contemporaries, particularly the F-8 Crusader and the Super Scimitar. As Khrushchev had planned to scrap the carrier force anyway, no successor model came up during the 1950s. A missile armed interceptor to replace the Yak-31 was not approved prior to 1961, when Admiral Gorshkov was in a position to decide on development efforts over Khrushchev’s head. This time, only the Yakovlev OKB was asked to present a design, and they decided to play things conservatively and utilize wings and control surfaces of the Yak-28 multirole plane family. The hull was of new construction and contained an Oryol radar for its main armament of four R-98 (AA-3) missiles. Guns were not mounted initially. Two Tumansky R-11 engines with reheat (46/62 kN) were placed in nacelles at the hull sides (rather than separately under the wings as in the Yak-28). Weighing 9 tons empty and 15 tons fully loaded, these planes had the maximum weight Kronshtadt’s catapults could handle. The new interceptor was capable of Mach 1,65 at optimum height, but not much of a dogfighter; stall speed in particular was rather high. The hull contained large internal fuel tanks allowing a radius of action exceeding 900 kilometers (ferry range 2700 kilometers on internal fuel). The first prototype took off late in 1963, and tests were completed by mid-1965.

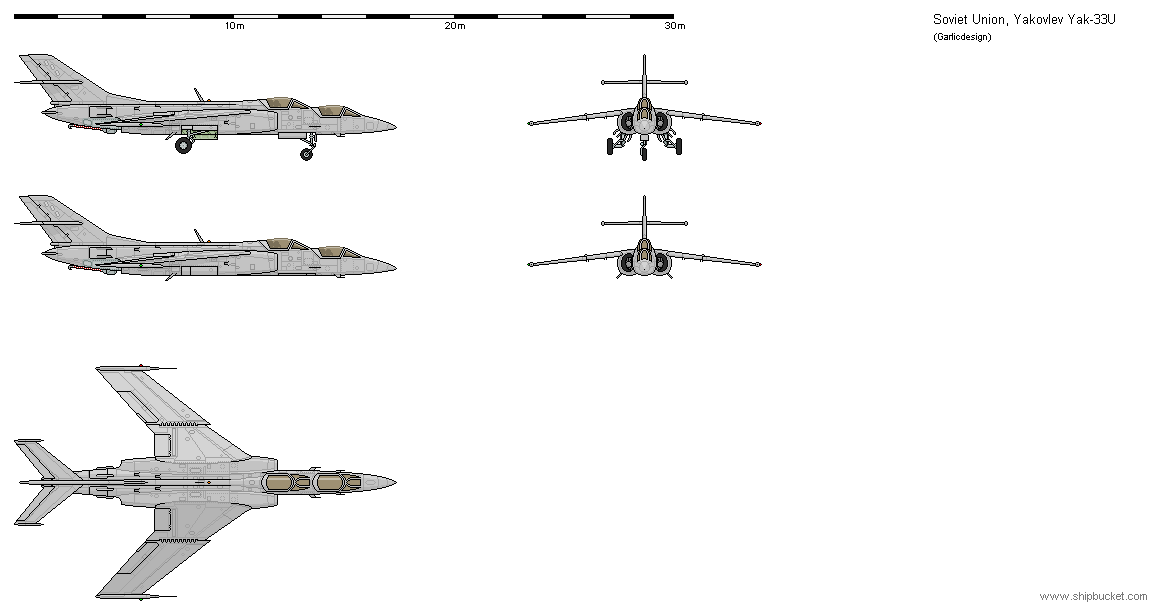

With the Yak-31 critically obsolete, the new machine was commissioned as the Yak-33 early in 1966, and an initial order of 75 was placed, including 15 Yak-33U double-seaters. The latter featured the peculiar double cockpit approach also used for the trainer versions of the Yak-28.

Carrier operations commenced in 1967 on Moskva; Kronshtadt, which still had a straight flight deck, retained Yak-31s for the time being (the carrier was modified with an angled deck from 1969 through 1971 and received a Yak-33 squadron afterwards. Operation of this large, heavy and powerful plane proved difficult for the Soviets, who were used to much lighter and more docile aircraft, and several accidents occurred, earning the Yak-33 the nickname ‘Red Scimitar’ for the similarly troublesome British fighter. As with the Yak-31, Yak-33s NATO reporting name contained a pun. Due to its similarities with the Scimitar (both in terms of general configuration and propensity to crashes), the fighter was named ‘Falchion’. Despite all teething troubles, the Yak-33 had completely replaced the Yak-31 by mid-1969.

The trainers were assigned the NATO reporting name Minion. They operated from ground bases and only visited the carriers for launch and recovery exercises.

The Falchion would continue to serve throughout the 1970s, and over time, its reputation improved (another similarity to the Scimitar). As the Soviet carrier fleet increased, a repeat order of another 75 Yak-33s (again with 15 trainers) was issued in 1973, and a third order of 25 machines to replace attrition went out in 1976. The last batch was of the Yak-33M type and featured newer versions of radar and missiles, improved commo and ECM gear, and a twin 23mm gun slung under the hull. The earlier machines were retrofitted between 1978 and 1980. In that year, the Soviet Navy operated four fleet carriers and had a maximum of six squadrons of Yak-33s embarked (one each on Moskva and Leningrad, two each on Kiev and Minsk); two more operated from ground bases, and one OCU provided conversion training. From 1978, a new camouflage livery was trialed on Leningrad, but not generally introduced.

After twelve years of faithful service, replacement of the Yak-33 with MiG-23Ks commenced in 1979. By 1985, all Falchions were retired.

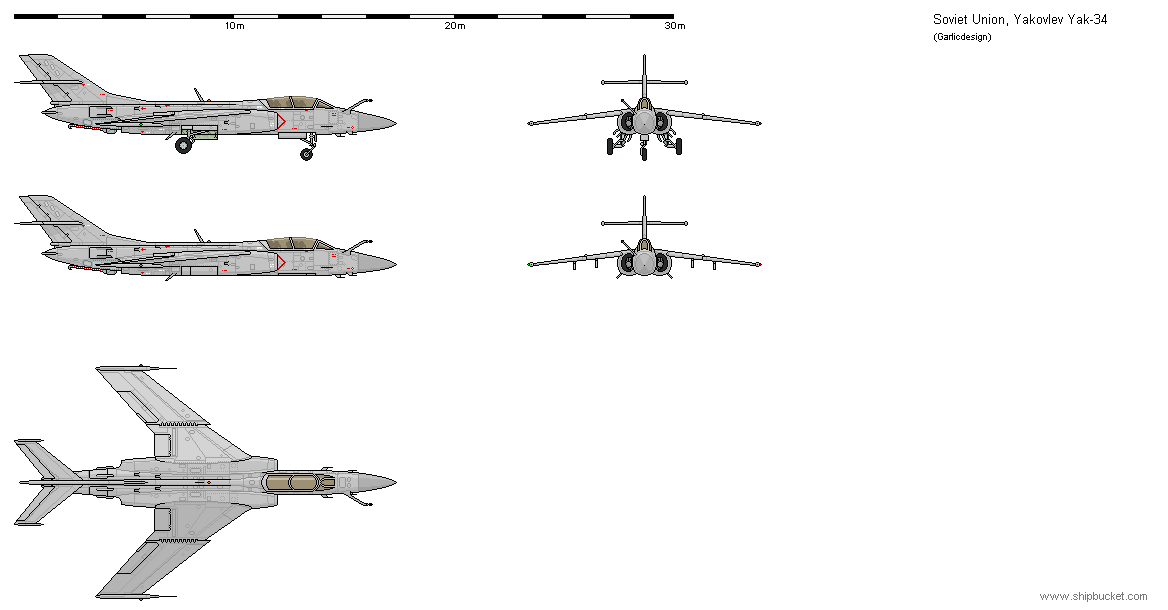

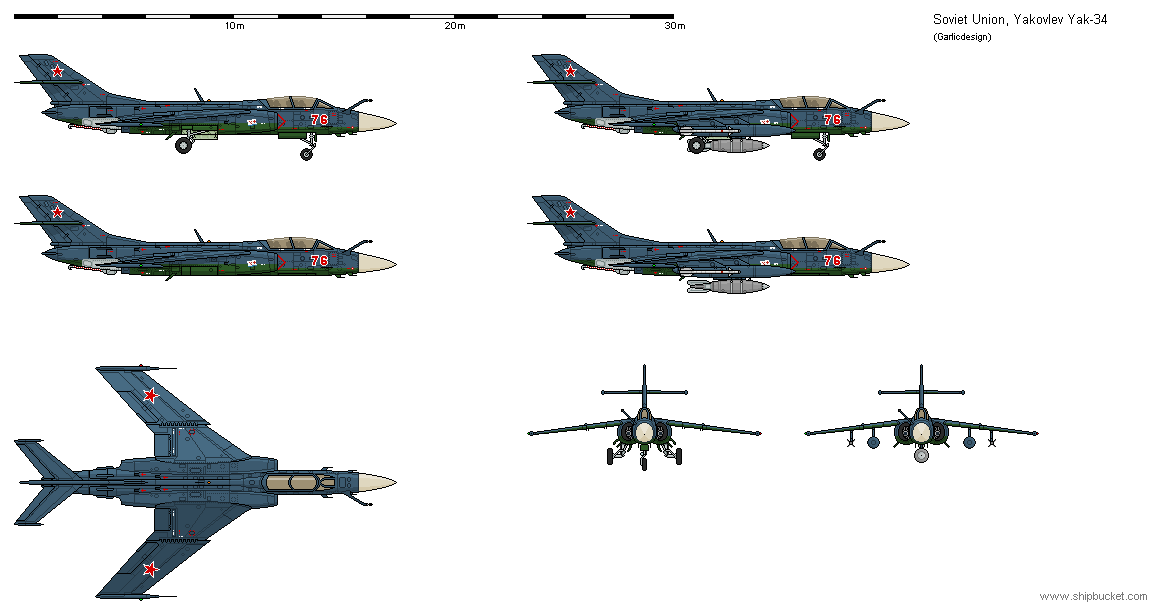

Like the Yak-31, the Yak-33 also spawned a dedicated strike version to replace the hopelessly outdated Tu-18. Unlike the Yak-31, this version was not added as an afterthought, but part of the development effort from the beginning. The forward hull was somewhat lengthened and a tandem cockpit was installed, and the avionics and radar suite was optimized for the naval strike role. Speed was only marginally less at Mach 1,6, all other particulars being the same; weapons load was 4.000 kilograms.

In accordance with the custom to assign even numbers to bomber aircraft, the strike variant was dubbed Yak-34; its NATO reporting name was Brawler. Development was protracted on account of the relatively sophisticated avionics suite; by the time they became available in 1971, the Tu-18 fleet was barely serviceable. 60 Yak-34s – ordered in 1966 – were delivered in 1971 and 1972, and one squadron each embarked on Moskva and Leningrad. They were cleared for nuclear gravity bombs from the beginning, carrying K-13 (AA-2) missiles for self defence.

A repeat order of another 60 machines was issued in 1972 to equip the upcoming Pr.1153 Kiev-class carriers; each of them was designed to embark two squadrons of Yak-33s and two of Yak-34s, plus ASW/tanker assets and rescue helicopters. As four of the new carriers were to be commissioned by 1985, 60 more Yak-34s were ordered in 1976, plus another 20 Yak-33Us for conversion training. The third batch – delivered from 1980 – was equipped to fly SEAD missions with Kh-58 (AS-11) missiles, carrying Vyuga targeting pods and SPS jamming pods.

Production was complete in 1982 at 145 Yak-33s, 50 Yak-33Us and 180 Yak-34s; when the last Kiev-class carrier entered service in 1986, 20 Falchions were still in service on Moskva and Leningrad, plus no less than 120 Brawlers (10 on each carrier and another 60 with six land-based squadrons). During the 1980s, the Yak-34 were retrofitted to carry Kh-25 (AS-12) and Kh-29 (AS-14) missiles.

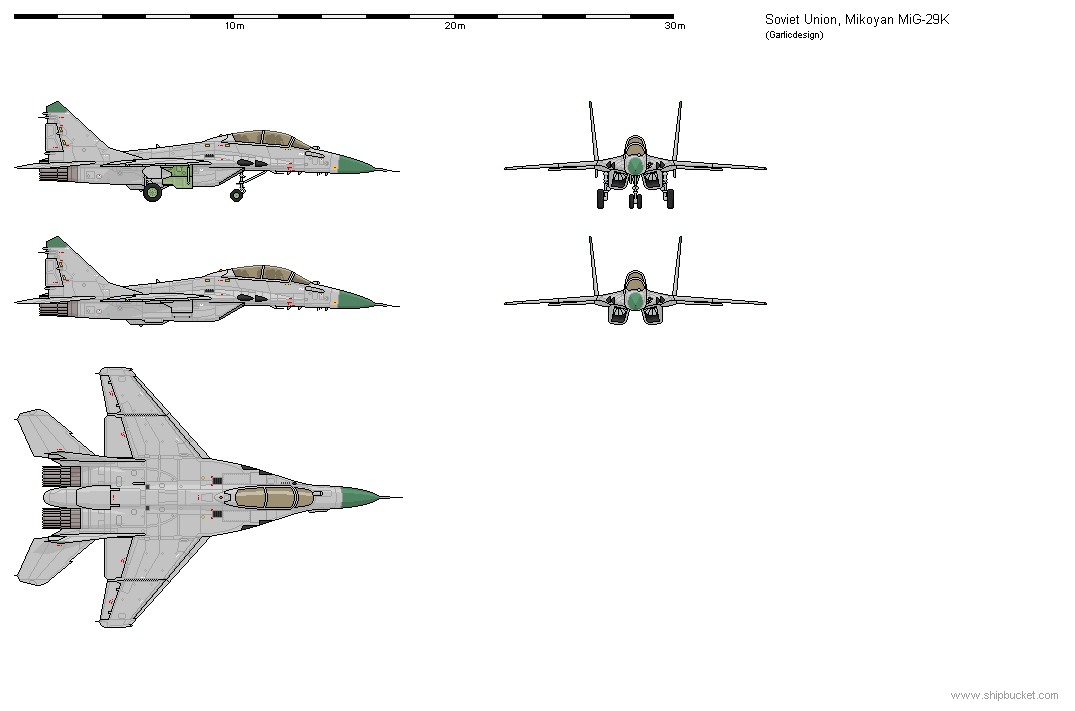

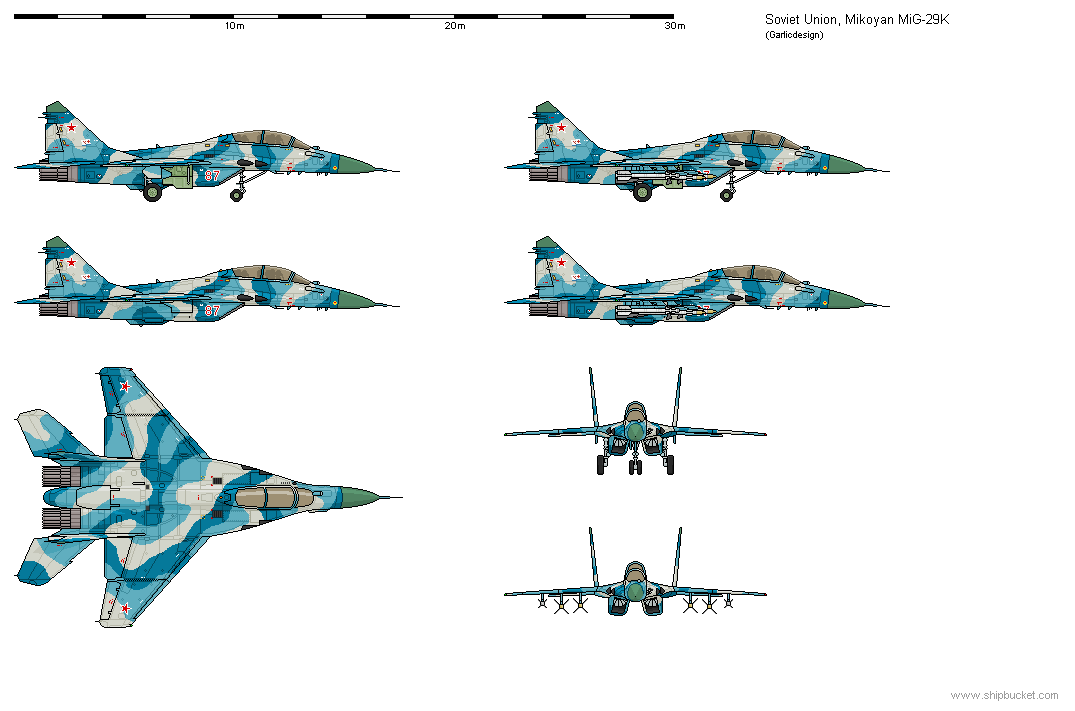

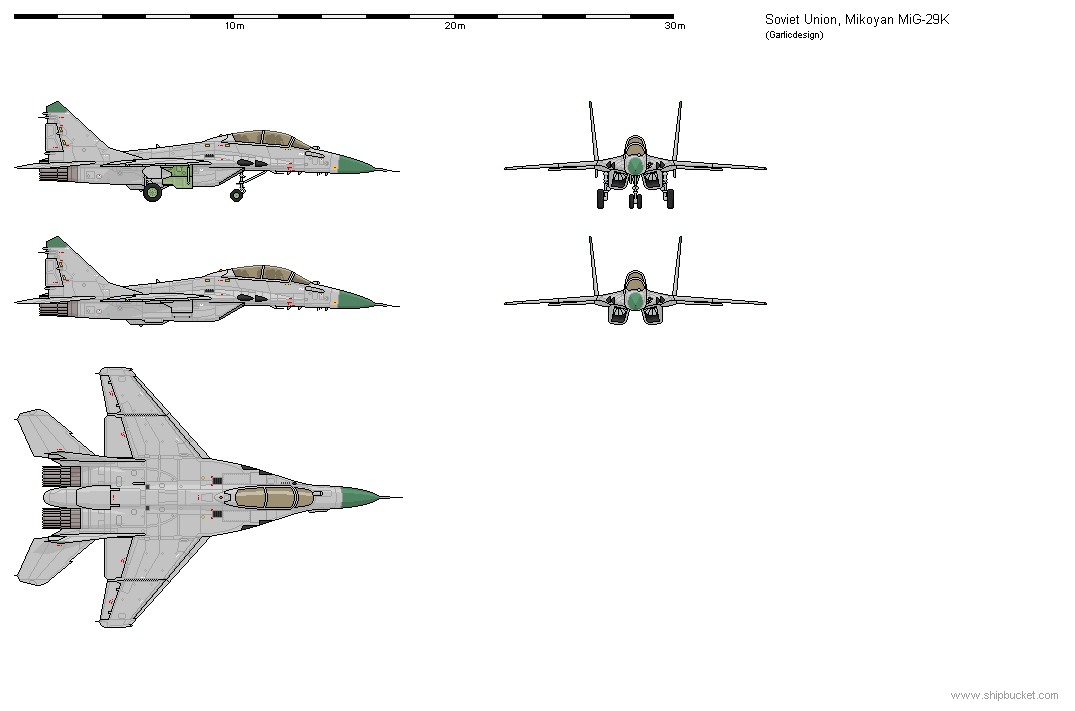

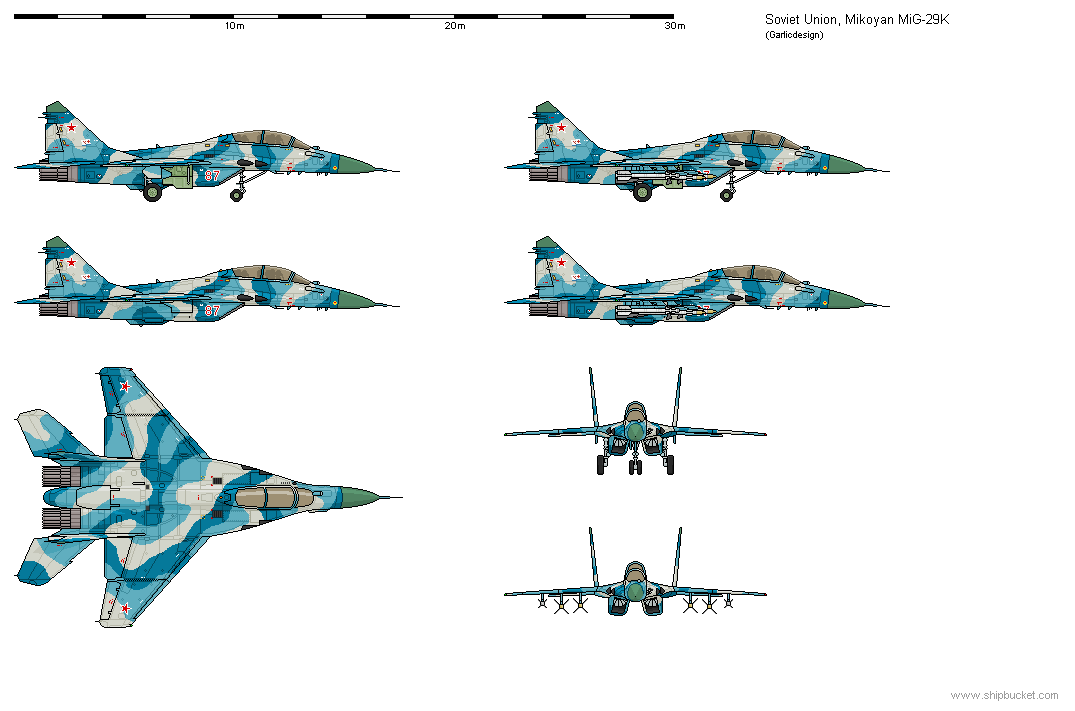

A replacement for the Yak-34 was to be made available by 1990. Yakovlev offered a navalized version of their multirole fighter Yak-43, which however failed every timeline and eventually vanished in development limbo. Sukhoi’s navalized Su-24 and Su-25 were rejected as too large and too slow, respectively; the Su-33 was strictly air-to-air. This only left Mikoyan’s MiG-29K, which was fully strike capable and thus chosen to take the mantle of both the MiG-23K and the Yak-34. Mikoyan tried to do its job thoroughly and needed till 1996 to make the omnirole MiG-29K work; after strenuous carrier service, the Yak-34 – essentially a 1960s design with a projected lifetime of ten years – could not be made to last that long. Only the final batch delivered in 1980/2 was still available after 1990, and they were retired in 1995 after several groundings following fatigue-related crashes.

To be continued

GD

Russian Carrier Aviation 1945 – 2020 (Thiariaverse edition)

1. The 1950s

In 1948, the Soviet Union was in possession of three aircraft carrier hulls: The badly damaged German Graf Zeppelin, the incomplete Japanese Kaimon and the fully operational Thiarian Feinics. The German ship was in a wretched state and offered no growth potential, so she was discarded and used up for trials in 1953. Feinics was commissioned for trials in 1950 and renamed Kraznaya Zvezda, with an air group consisting of WWII vintage La-11K and Su-6K aircraft and used to train carrier pilots and develop an operational doctrine. Kaimon was laid up to await a decision on her further use. Stalin was as determined as ever to create a Soviet Blue Water Navy to rival the might of the USN and ordered to complete Kaimon to a revised design heavily influenced by Feinics, and to build an enlarged copy of Feinics named Kronshtadt. That vessel was ten meters longer than Feinics, displaced 5.000 tons more and had a larger island with integral funnel and longer, if still hydraulic catapults. Two additional ships were planned to be laid down in 1955, after initial experiences with the first two ships could be evaluated. The rebuild of Kaimon ran into trouble due to her very flimsy construction and ergonomic unsuitability for cold climates and was abandoned in 1954 after very little progress, but Kronshtadt was laid down in 1950, launched in 1953 and completed in 1956, fully on schedule. Even Khrushchev, who did not believe in conventional forces and focused Soviet efforts on nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, approved Kronshtadt’s completion because she was so far advanced already that scrapping her would have been wasteful. By 1959, the Soviet Union thus was in possession of two conventionally powered straight-decked aircraft carriers. Kraznaya Zvezda was limited to aircraft of eight tons MTOW due to the limited power of her single catapult; Kronshtadt had two catapults capable of shooting fifteen tons each into the air. Thus, Kraznaya Zvezda was only ever used for training, and only Kronshtadt was capable of operating the new generation of Soviet carrierborne nuclear-capable heavy strike aircraft.

1.1. Lavochkin La-11K ‘Fang’

The first Soviet carrierborne fighter was a straightforward upgrade of the land-based La-11 and quite obsolete when Kraznaya Zvezda was commissioned in 1950. Adding arrestor hooks and catapult fittings did no good to the performance envelope of an already overweight design, and their fighting power was rather symbolic.

The Lavochkin fighters remained in service for five years till enough Yak-31s were available.

Although they never saw serious action, they were immensely valuable in developing carrier operation routines, at which the Soviets were complete virgins when the La-11 entered service.

1.2. Sukhoi Su-6MK ‘Brick’

The Su-6M was a rather random choice for the naval strike and torpedo bomber role, whose only virtue was the use of the same ASh-82 engine also installed in the La-11. The type had been a backup for the Il-2, but never seen much production due to the lack of the originally planed M-71 engine and the unsuitability of the AM-42 that was substituted; the Ash-82 installed in the naval version was weaker than either, and eschewing armour protection was compensated by the added weight of catapult fittings, sea rescue gear and arrestor hooks.

The result was a seriously underpowered airplane which was unable to perform its assigned mission, resulting in the aptly chosen NATO reporting name Brick. The Su-6 only ever performed training operations and was replaced by the infinitely more capable Tu-18 as soon as possible.

By 1958, the last naval Su-6 was retired.

1.3. Yakovlev Yak-31/32 ‘Fenian/Frolic/Mastiff’

For the fighter role of the new Soviet naval aviation, Yakovlev’s proposal beat similar designs by Lavochkin and Mikoyan. The plane received the internal numeral Yak-70 by the Yakovlev OKB. It was a straightforward upscale of the Yak-30 experimental light fighter to the size of the Yak-50 experimental interceptor; externally it resembled the latter more than the former, but retained the conventional tricyclic landing gear of Yak-30 which was expected to offer superior stability for carrier deck operations. Internal structure was strengthened, the landing gear was made sturdier, an arrestor hook was fitted and every inch of the airframe was crammed with fuel tanks to attain maximum range. Being a modification of existing designs, development was quick, and the Yak-70 prototype had its first flight in October 1951. Empty weight was 4.250 kilograms, over a ton more than the land-based Yak-50, and MTOW was a whopping 6.500 kilograms. Armament consisted of three 23mm cannon; there were four underwing hard points, all of which were wet to enable the Yak-70 to maximize its fuel load for long-range maritime missions. Weapons load was set to 1.200 kilograms. Like most Soviet fighters of the age, the Yak-70 was powered by a single Klimov VK-1 turbojet with 27 kN thrust and displayed good agility and pleasant flying characteristics, although it had become a bit too heavy for its somewhat anemic engine, resulting in a rather slow climb and some trouble with catapult shots during trials, including two prototype crashes. The issue could be resolved by fitting an afterburner to the VK-1 in mid-1952, creating the VK-1F which was also installed in the Air Force’s MiG-17, providing 34 kN wet thrust. In this shape, the Yak-70 was approved by the AVMF in 1953 and commissioned as the Yak-31.

Series production commenced in September 1953, several months after Stalin’s death. A two-seat trainer version Yak-31UTI (up to that time, the Soviet Navy had no jet-qualified pilots) was commissioned early in 1954; initial orders covered 60 fighters and 15 trainers. The trainers had one less 23mm cannon than the fighters and shorter range due to smaller hull fuel tanks. Deliveries were complete in early 1956.

Flight operations aboard Kraznaya Zvezda commenced in May 1955, with a single Yak-31 squadron replacing the ancient La-11s (the Su-6K bombers would remain in service till 1958). By mid-1956, the new carrier Kronshtadt embarked two squadrons of Yak-31s and one of Tu-18s. As the new fighter had first entered service upon an ex-Thiarian carrier, the NATO reporting name pretty much chose itself: Fenian-A.

The operational squadron aboard Kraznaya Zvezda was replaced by a trainer squadron in 1957 in characteristic high visibility markings. The YAK-31UTI was assigned the reporting name Mastiff-A.

That year, a repeat order for another 60 Yak-31 and 15 Yak-31UTI was issued, because the initial training cycle had resulted in several crashes and other write-offs. Air-to-air missiles had been made available by that time, and it was decided to fit the Yak-31 with a RP-2U Izumrud radar and arm it with two or four K-5 (AA-1) missiles. Unlike other early Soviet missile armed fighters, the Yak-31PM retained two 23mm cannon.

Due to somewhat higher weight, performance suffered a little, and as all hard points were now occupied with missiles, range suffered a little more. The added all-weather performance however was considered worth the trade-offs. All 60 machines of the repeat order were delivered as Yak-31PM, while the trainers were identical to the basic Yak-31UTI. Deliveries were complete by mid-1958. The Yak-31PM was designated Fenian-B by NATO.

By that time, the AVMF had decided to add strike power to its carrier force and embark a fourth squadron by introducing permanent deck parking. The standard Yak-31 was no great attack plane and needed tob e heavily modified. To attain the necessary range for antiship strike missions, Yak-31s forward hull needed to be reshaped; all electronic gear was relocated into the forward hull, which received a pointed cone, and the air intakes were relocated to the wing roots. This allowed for additional fuel tanks in the hull behind the cockpit for a 30% increase in range over the Yak-31MP. Weapons load increased to 2.000 kg (not counting two 23mm cannon and their ammunition) and MTOW to 7.500 kg. The higher weight was offset by installing a newer Tumansky RD-9BF powerplant of 29 kN dry thrust, with 37 kN on reheat; improved aerodynamics of the new nose also helped to retain the same flight performance as the original Yak-31. The revised design (named Yak-75 by the OKB) differed sufficiently to warrant a new official designator too; in keeping with assigning even numbers to strike aircraft, this variant was commissioned as the Yak-32 in 1960.

60 machines were produced till late 1961, plus another ten standard Yak-31UTI trainers. The Yak-32 also received a new NATO reporting name; unlike the basic version, this time it was randomly assigned: Frolic-A.

Although by then enough planes to equip them were available, the two additional carriers planned for 1955 never materialized. Those Yak-31s not needed for shipboard operations were employed as fighter cover for Soviet naval bases in the arctic; although jet fighter development in the second half of the 1950s rendered them rapidly obsolescent, Khrushchev approved no replacement prior to the sobering experience of the cuban missile crisis in 1961, which sparked further carrier construction (see 1960s below). In order to prepare the AVMF for this surge in size, another thirty Yak-31UTI were built in 1961/2, plus a repeat order for 40 Yak-32 and 40 Yak-31PM, which were fitted with the DR-9BF engine of the Yak-32. They were dubbed Yak-31PFM upon completion (NATO reporting name Fenian-C). Although the type was clearly obsolescent, it was all that was available at the time. A final lot of 50 Yak-31UTI was added in 1964/5. Including prototypes, production totaled 392, of which 120 were trainers.

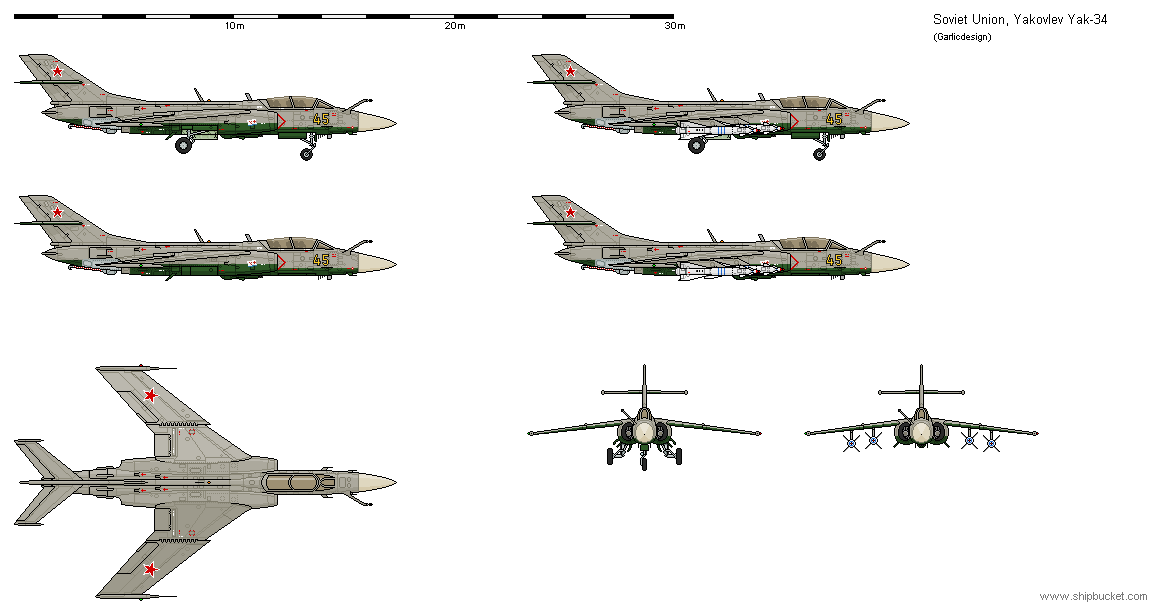

As development of the ambitious replacement project Yak-33/34 dragged on longer than expected, the Yak-31/32 soldiered on throughout most of the 1960s. Some 30 remaining original Yak-31s were relegated to the land-based strike role in 1961 and based on the Crimea. They received a four-colour camouflage paintjob, and arrestor hooks and catapult fittings were removed. They were only capable of employing dumb bombs and unguided rockets; their designation was now Yak-31B and their reporting name changed to Fenian-D. The last of them were de-commissioned in 1968.

The Yak-31PM were refitted to carry the new K-13 (AA-2) air-to-air missile (both in IR and SARH mode) in 1962/3; the Yak-31PFM carried it from the start, just like the RWR, which was retrofitted to the Yak-31PM (new NATO reporting name Fenian-E). When commissioned in 1964, the Yak-31PFM were the first Soviet naval aircraft to receive the new blue paintjob with green anti-corrosive paint on the underside, which was to remain standard for a quarter century. Although the most mature version oft he Yak-31, the PFM had the shortest career, because they were supplanted by the brand-new Yak-33 starting in 1966; the last Yak-31PM retired in 1967, and the last Yak-31PFM in 1969. As the latter were still rather new, 25 hulls were rebuilt to Yak-31UTI trainers. All others were either displayed or scrapped.

The Yak-32 needed to stay in service even longer, because full development of the Yak-34 strike fighter took till 1971, and the latter aircraft’s size prompted development of a smaller strike fighter (the Yak-39) which would not become available before 1976. The Yak-32s were adapted to fire Kh-66 (AS-7) missiles in 1968, also receiving a RWR, a navigation radar, a targeting system for the AS-7 and two more hard points under the air intakes (Yak-32M, reporting name Frolic-B). By 1970, all three Soviet carriers (Kronshtadt, Moskva and Leningrad) had one squadron of 18 Yak-32s embarked (12 on Kronshtadt); the new Pr.1153 Kiev-class carriers were equipped with Yak-34s from the start. Replacement oft he Yak-32 with Yak-39 commenced in 1976 and was complete in 1979.

The Yak-31UTI had the longest career, remaining AVMF’s prime advanced trainer for carrier operations until well into the 1980s; mostly operating from Kronshtadt, which was relegated to the training role in 1975 when Kraznaya Zvezda was scrapped. A hundred were available in 1970 (including 25 rebuilt Yak-31PFMs), and they were not entirely replaced before 1985, when enough Yak-39UTIs for carrier training ops were available.

Although produced in tiny numbers by Soviet standards and never exported, the Yak-31/32 family was invaluable to gather the kind of experience in carrier aviation that was necessary to establish the Soviet Navy as a true blue water force.

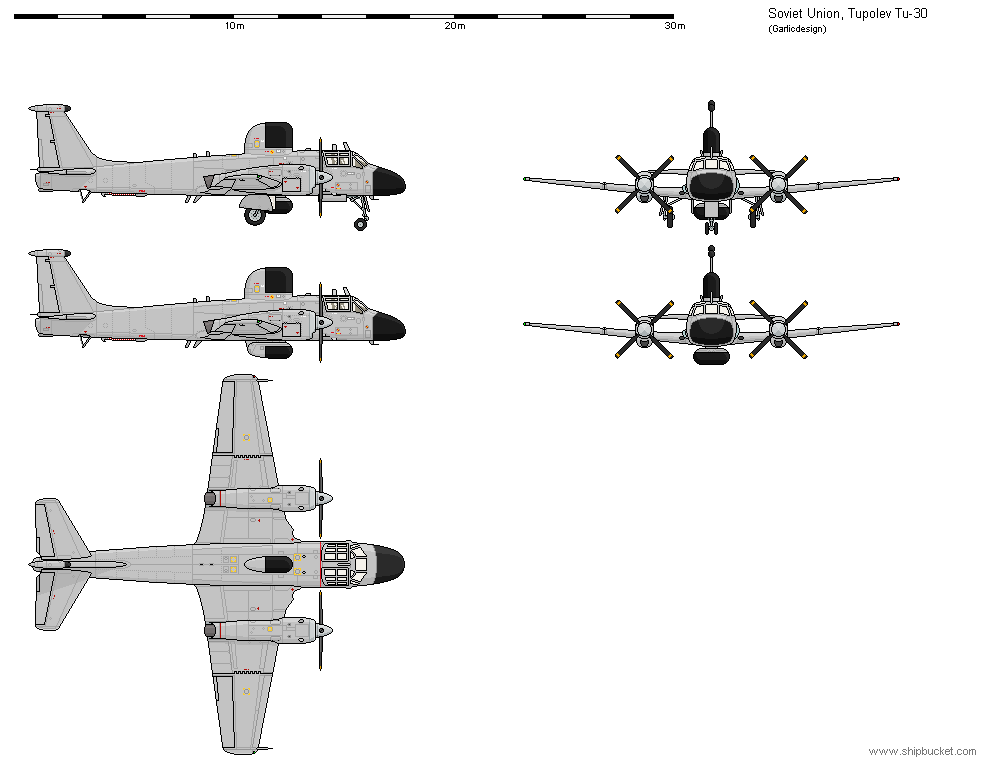

1.4. Tupolev Tu-18 ‘Boot’

Development of a specialized carrierborne strike aircraft commenced in 1949 on Stalin’s orders. Tupolev chose a single-engined turboprop-powered approach, utilizing the new Kuznetsov TV-2M turboprop developing 7.650 shp. The attempt to attain optimal visibility for the two-man crew resulted in a side-by-side cockpit arrangement at the extreme forward end of the fuselage, only a meter behind the six-bladed contra-rotating propeller. They were armed with two 23mm cannon in the wings for strafing and another two in an automatic radar-guided tail turret for self defence. The airplane, dubbed Tu-91 by the Tupolev OKB, could only be described as extremely ugly.

Nevertheless, when it first flew in 1954, performance was convincing. The prototype met the speed requirement of 800 kph and exceeded the payload requirement of 1.500 kg more than twice over; in service, the type was cleared for 3.200 kilograms. Range was excellent due to the economic turboprop propulsion and the large internal fuel supply; with 2.000 kilograms of payload, a combat radius of 1.000 km was attained. The hull was robust, maintenance requirements were moderate despite the somewhat experimental engine, and flight characteristics were pleasant. Although Khrushchev himself ridiculed the Tu-91s looks, he approved a limited production run of 75 machines to equip two carrier-based squadrons and an OCU of nine each, and two land-based squadrons of twelve each, plus attrition replacements. The planes received the service designation Tu-18 and the NATO reporting name Boot. The first squadron was commissioned in 1957 and embarked on the brand-new carrier Kronshtadt. Unlike contemporary jets, which were painted silver, they still carried the AV-MF’s WWII-vintage blue-grey livery. Typical armament would comprise two 500 kg bombs and eight big 240mm rockets.

By 1959, all 75 Tu-18 were in service; one squadron each was based on Kronshtadt and Kraznaya Zvezda, and the land-based units were based in the Far East. In 1960, the type was cleared for AN-28 nuclear gravity bombs, and in 1962, radar was retrofitted in ventral pods behind the bow wheel well. The automatically fired self-defense cannon aft, which never worked satisfactorily, were removed during this refit.

Despite its initially good performance, the Tu-18 did not age well. Their radars did not work because of interference from the contra-rotating propellers, and their speed was thoroughly unimpressive by 1960s standards. Integration of more modern weapons proved impossible, and the type’s prominent size limited air group strength on the smallish Soviet carriers. Nevertheless, the Tu-18 was kept in service till 1973 as the fleet’s dedicated nuclear weapons carrier. As antisubmarine patrol aircraft (although ill-equipped for this task) and tankers, they lingered till 1985.

They were replaced in the bomber role by the Yak-34 from 1971 and in their other tasks by the Tu-24, which had been developed from Tu-18s airframe, from 1976.

2. The 1960s

Khrushchev was never happy with having to spend money on anything but big nukes and in 1960 announced to de-commission the carriers by 1961 at latest, after only five years of operations. But during the Cuban missile crisis of 1961, Kronshtadt suddenly found herself at the center of a Soviet task force also containing the ex-Thiarian battlecruiser Arkhangelsk (ex-Caithreim) headed for the central Atlantic. The Russian naval aviators achieved nothing, facing five US carrier battlegroups outnumbering them 15:1 in aircraft, but proved that they had mastered carrier operations. With Khrushchev’s authority somewhat shattered by the outcome of the Cuban crisis, Admiral Gorshkov managed to prevail on the Supreme Soviet to approve construction of two carriers to an all new design code-named PBIA in 1961, and to order development of a replacement for the Yak-31/32 for deployment in 1965 at the latest. PBIA was originally to be nuclear-powered, but rather small; the final design had a conventional steam plant and was somewhat larger, becoming the Moskva-class, commissioned in 1967 and 1969.

2.1. Yakovlev Yak-33/34 ‘Falchion/Brawler/Minion’

Although the Yak-31 had been a satisfactory little plane, it was a far cry performance-wise from its western contemporaries, particularly the F-8 Crusader and the Super Scimitar. As Khrushchev had planned to scrap the carrier force anyway, no successor model came up during the 1950s. A missile armed interceptor to replace the Yak-31 was not approved prior to 1961, when Admiral Gorshkov was in a position to decide on development efforts over Khrushchev’s head. This time, only the Yakovlev OKB was asked to present a design, and they decided to play things conservatively and utilize wings and control surfaces of the Yak-28 multirole plane family. The hull was of new construction and contained an Oryol radar for its main armament of four R-98 (AA-3) missiles. Guns were not mounted initially. Two Tumansky R-11 engines with reheat (46/62 kN) were placed in nacelles at the hull sides (rather than separately under the wings as in the Yak-28). Weighing 9 tons empty and 15 tons fully loaded, these planes had the maximum weight Kronshtadt’s catapults could handle. The new interceptor was capable of Mach 1,65 at optimum height, but not much of a dogfighter; stall speed in particular was rather high. The hull contained large internal fuel tanks allowing a radius of action exceeding 900 kilometers (ferry range 2700 kilometers on internal fuel). The first prototype took off late in 1963, and tests were completed by mid-1965.

With the Yak-31 critically obsolete, the new machine was commissioned as the Yak-33 early in 1966, and an initial order of 75 was placed, including 15 Yak-33U double-seaters. The latter featured the peculiar double cockpit approach also used for the trainer versions of the Yak-28.

Carrier operations commenced in 1967 on Moskva; Kronshtadt, which still had a straight flight deck, retained Yak-31s for the time being (the carrier was modified with an angled deck from 1969 through 1971 and received a Yak-33 squadron afterwards. Operation of this large, heavy and powerful plane proved difficult for the Soviets, who were used to much lighter and more docile aircraft, and several accidents occurred, earning the Yak-33 the nickname ‘Red Scimitar’ for the similarly troublesome British fighter. As with the Yak-31, Yak-33s NATO reporting name contained a pun. Due to its similarities with the Scimitar (both in terms of general configuration and propensity to crashes), the fighter was named ‘Falchion’. Despite all teething troubles, the Yak-33 had completely replaced the Yak-31 by mid-1969.

The trainers were assigned the NATO reporting name Minion. They operated from ground bases and only visited the carriers for launch and recovery exercises.

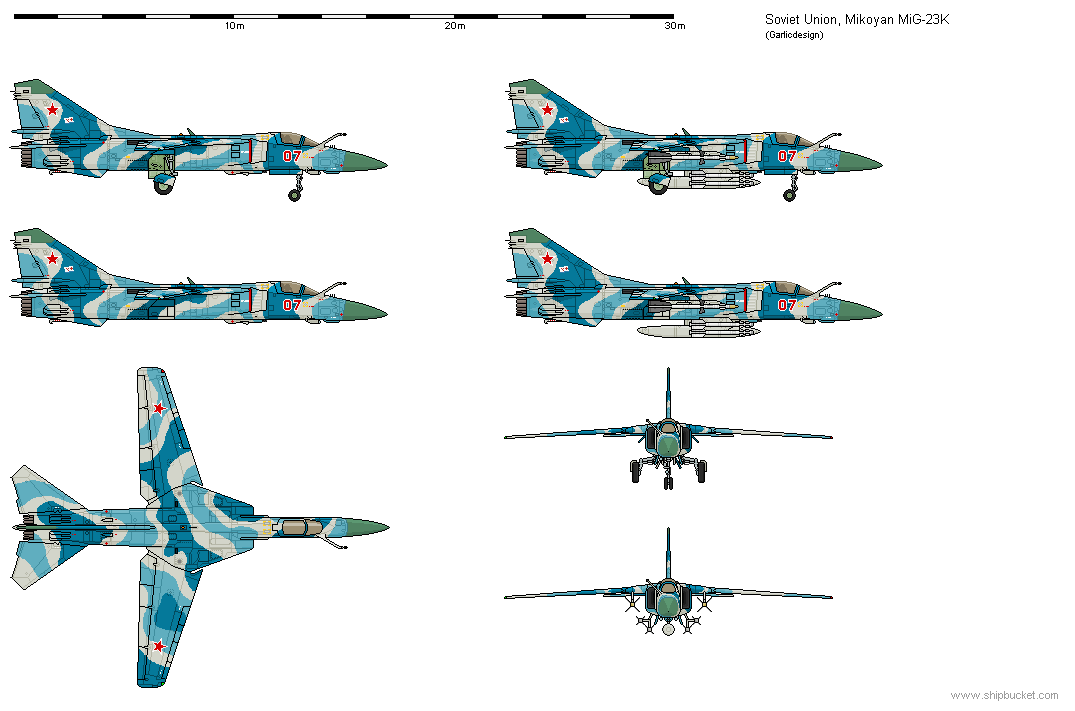

The Falchion would continue to serve throughout the 1970s, and over time, its reputation improved (another similarity to the Scimitar). As the Soviet carrier fleet increased, a repeat order of another 75 Yak-33s (again with 15 trainers) was issued in 1973, and a third order of 25 machines to replace attrition went out in 1976. The last batch was of the Yak-33M type and featured newer versions of radar and missiles, improved commo and ECM gear, and a twin 23mm gun slung under the hull. The earlier machines were retrofitted between 1978 and 1980. In that year, the Soviet Navy operated four fleet carriers and had a maximum of six squadrons of Yak-33s embarked (one each on Moskva and Leningrad, two each on Kiev and Minsk); two more operated from ground bases, and one OCU provided conversion training. From 1978, a new camouflage livery was trialed on Leningrad, but not generally introduced.

After twelve years of faithful service, replacement of the Yak-33 with MiG-23Ks commenced in 1979. By 1985, all Falchions were retired.

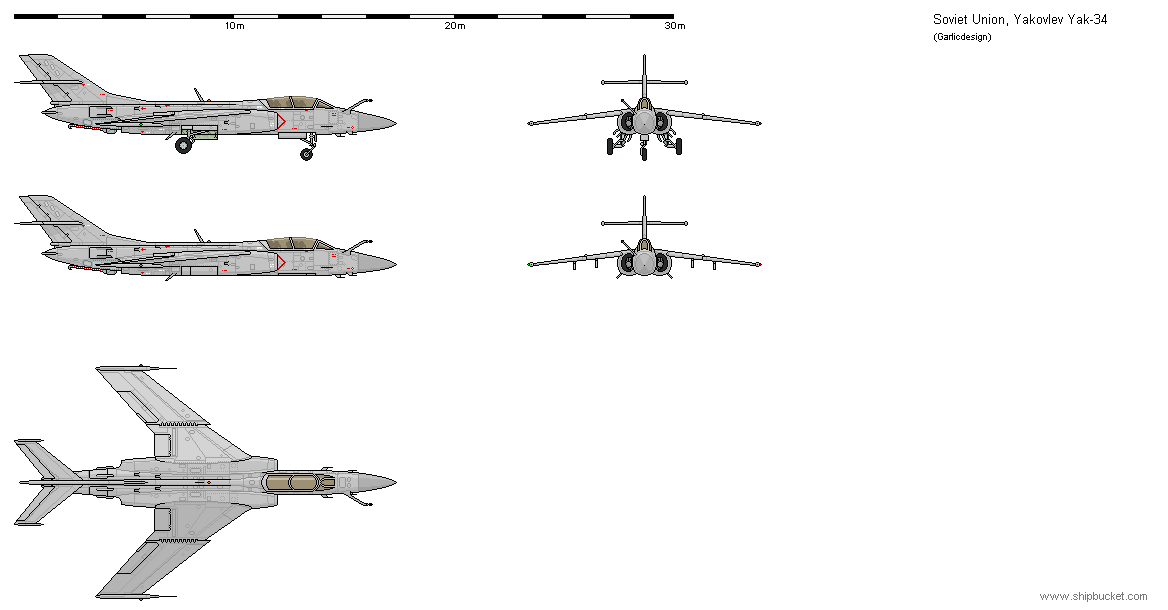

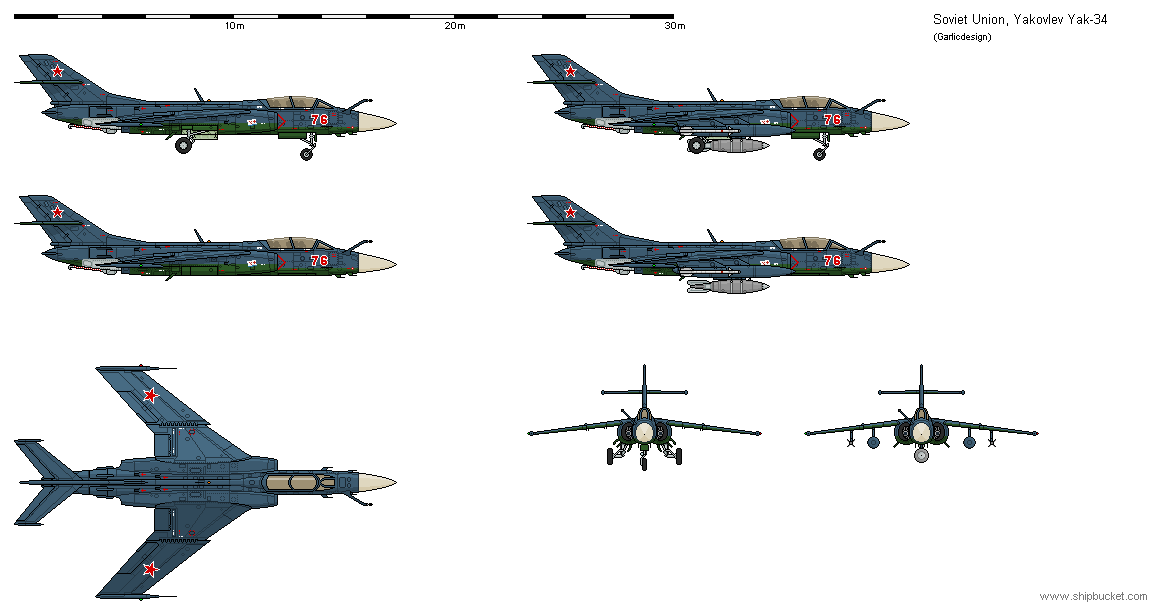

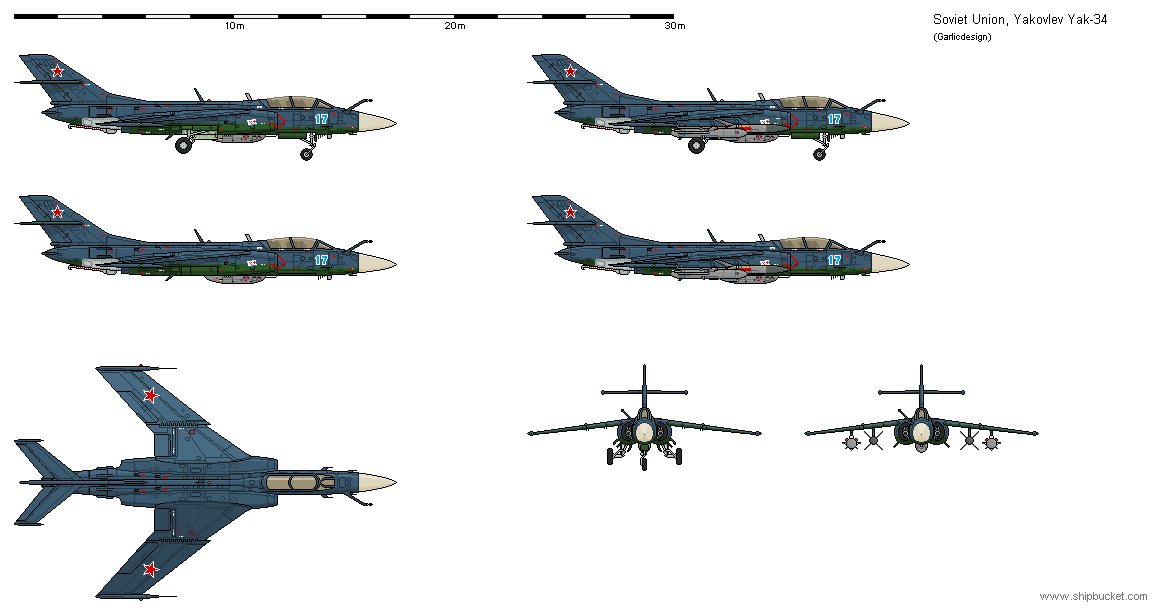

Like the Yak-31, the Yak-33 also spawned a dedicated strike version to replace the hopelessly outdated Tu-18. Unlike the Yak-31, this version was not added as an afterthought, but part of the development effort from the beginning. The forward hull was somewhat lengthened and a tandem cockpit was installed, and the avionics and radar suite was optimized for the naval strike role. Speed was only marginally less at Mach 1,6, all other particulars being the same; weapons load was 4.000 kilograms.

In accordance with the custom to assign even numbers to bomber aircraft, the strike variant was dubbed Yak-34; its NATO reporting name was Brawler. Development was protracted on account of the relatively sophisticated avionics suite; by the time they became available in 1971, the Tu-18 fleet was barely serviceable. 60 Yak-34s – ordered in 1966 – were delivered in 1971 and 1972, and one squadron each embarked on Moskva and Leningrad. They were cleared for nuclear gravity bombs from the beginning, carrying K-13 (AA-2) missiles for self defence.

A repeat order of another 60 machines was issued in 1972 to equip the upcoming Pr.1153 Kiev-class carriers; each of them was designed to embark two squadrons of Yak-33s and two of Yak-34s, plus ASW/tanker assets and rescue helicopters. As four of the new carriers were to be commissioned by 1985, 60 more Yak-34s were ordered in 1976, plus another 20 Yak-33Us for conversion training. The third batch – delivered from 1980 – was equipped to fly SEAD missions with Kh-58 (AS-11) missiles, carrying Vyuga targeting pods and SPS jamming pods.

Production was complete in 1982 at 145 Yak-33s, 50 Yak-33Us and 180 Yak-34s; when the last Kiev-class carrier entered service in 1986, 20 Falchions were still in service on Moskva and Leningrad, plus no less than 120 Brawlers (10 on each carrier and another 60 with six land-based squadrons). During the 1980s, the Yak-34 were retrofitted to carry Kh-25 (AS-12) and Kh-29 (AS-14) missiles.

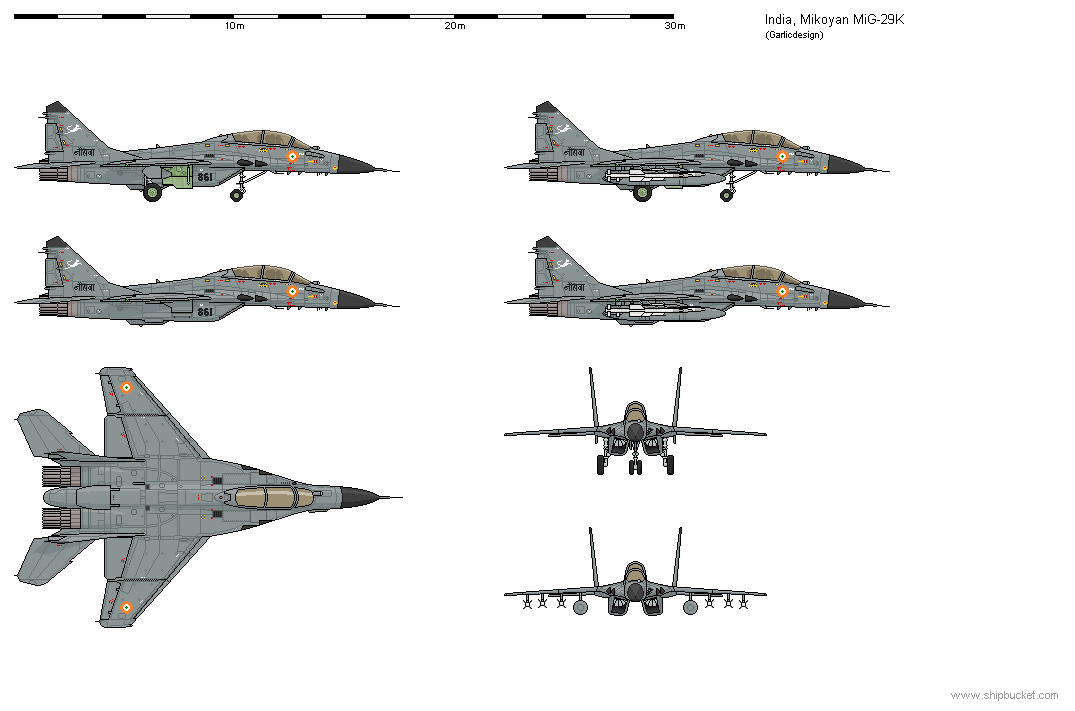

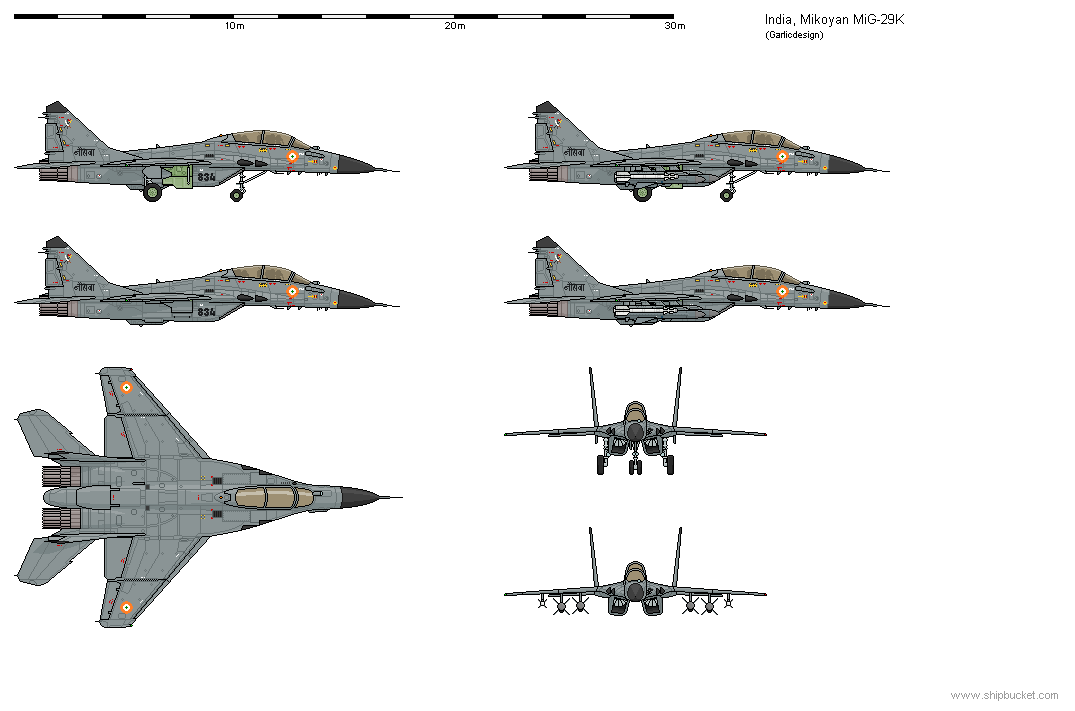

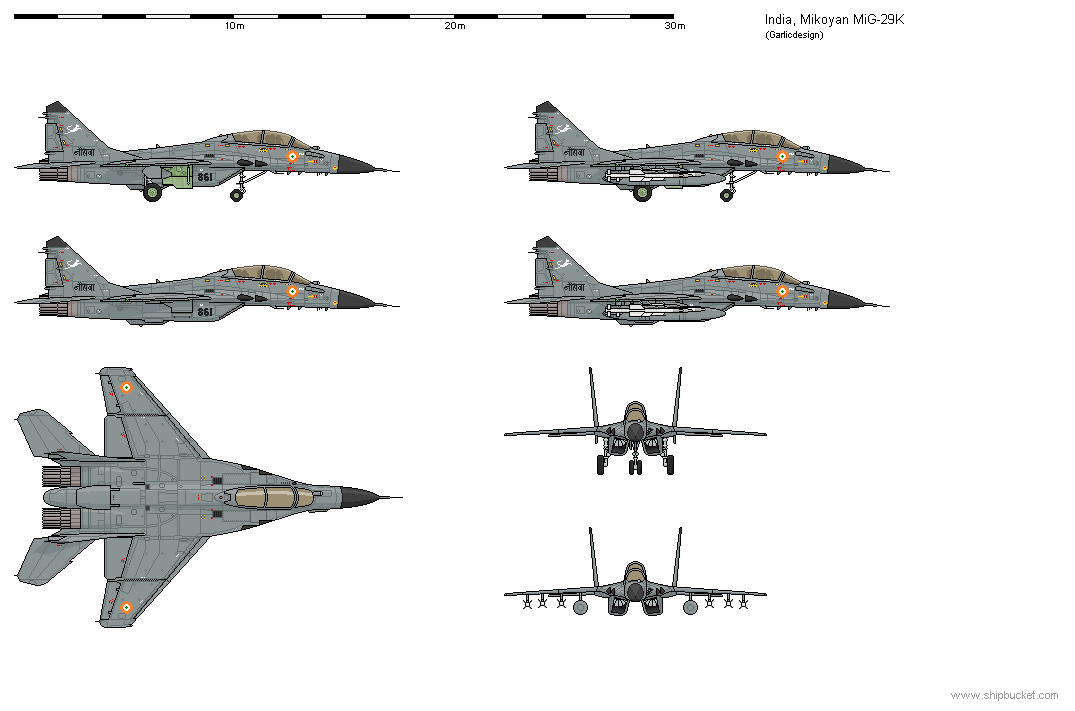

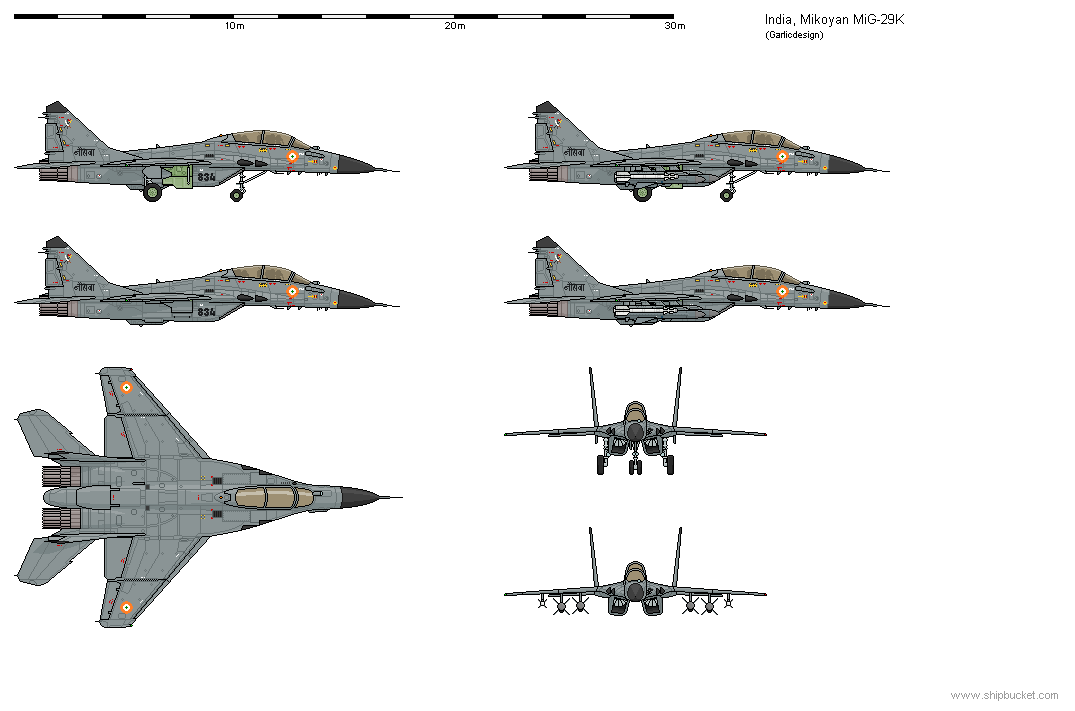

A replacement for the Yak-34 was to be made available by 1990. Yakovlev offered a navalized version of their multirole fighter Yak-43, which however failed every timeline and eventually vanished in development limbo. Sukhoi’s navalized Su-24 and Su-25 were rejected as too large and too slow, respectively; the Su-33 was strictly air-to-air. This only left Mikoyan’s MiG-29K, which was fully strike capable and thus chosen to take the mantle of both the MiG-23K and the Yak-34. Mikoyan tried to do its job thoroughly and needed till 1996 to make the omnirole MiG-29K work; after strenuous carrier service, the Yak-34 – essentially a 1960s design with a projected lifetime of ten years – could not be made to last that long. Only the final batch delivered in 1980/2 was still available after 1990, and they were retired in 1995 after several groundings following fatigue-related crashes.

To be continued

GD

Last edited by Garlicdesign on January 11th, 2020, 2:29 pm, edited 1 time in total.

- Garlicdesign

- Posts: 1071

- Joined: December 26th, 2012, 9:36 am

- Location: Germany

Re: Thiaria: Other people's airplanes

And on it goes…

3. The 1970s

After Khrushchev’s removal in 1964, Soviet military doctrine changed back towards a focus on conventional forces, influenced by Admiral Gorshkov and Marshal Grechko. As the 1970s marked the apex of economic development in the Soviet Union, funds were now available for Gorshkov’s grand scheme to turn the Soviet Navy into a blue water force to rival the USN. Of several competing carrier designs ranging in size from 85.000 down to 52.000 tons, the nuclear powered powered 60.000-ton Project 1150 was chosen for construction in 1968. Although the only shipyard capable of building a carrier of such size was Nikolayev and passage of capital ships (battleships and aircraft carriers) through the Dardanelles was prohibited by international treaties, a proposal to mount a battery of twenty-four P-500 (SS-N-12) antiship missiles and call the whole vessel a cruiser was rejected by Gorshkov as a poorly concealed cheat. If you have to cheat, he argued, go big and bold. Better not to impair aircraft carrying facilities by blocking half the available hangar space with useless missiles and call the ship a heavy aviation cruiser (Tyazhelniy Avianesushchiye Kreiser) anyway. The final design utilized an island design similar to the larger Project 1160 and carried heavy defensive weaponry: four twin 76mm guns, eight 30mm CIWS, two twin M-11 (SA-N-3) air defence missile launchers and four twin Osa-M (SA-N-4) point-defense missile launchers. Three catapults were provided, and a practical air group of 40 – 60 machines (depending on size) could be embarked. Four hulls were constructed, one after another, at Nikolayev: Kiev (commissioned 1976), Minsk (commissioned 1979), Novorossijsk (commissioned 1983), and Baku (commissioned 1987). As completed, Minsk had 100mm singles instead of 76mm twins and a modified radar suite, and the last two eschewed the guns altogether. They also had completely re-designed islands and swapped the obsolescent M-11 SAMs with Buk-M (SA-N-7) systems. Old Kraznaya Zvezda was scrapped in 1975. Kronshtadt had been taken in hand to receive an angled deck in 1971 and re-entered service in 1974 as a training carrier.

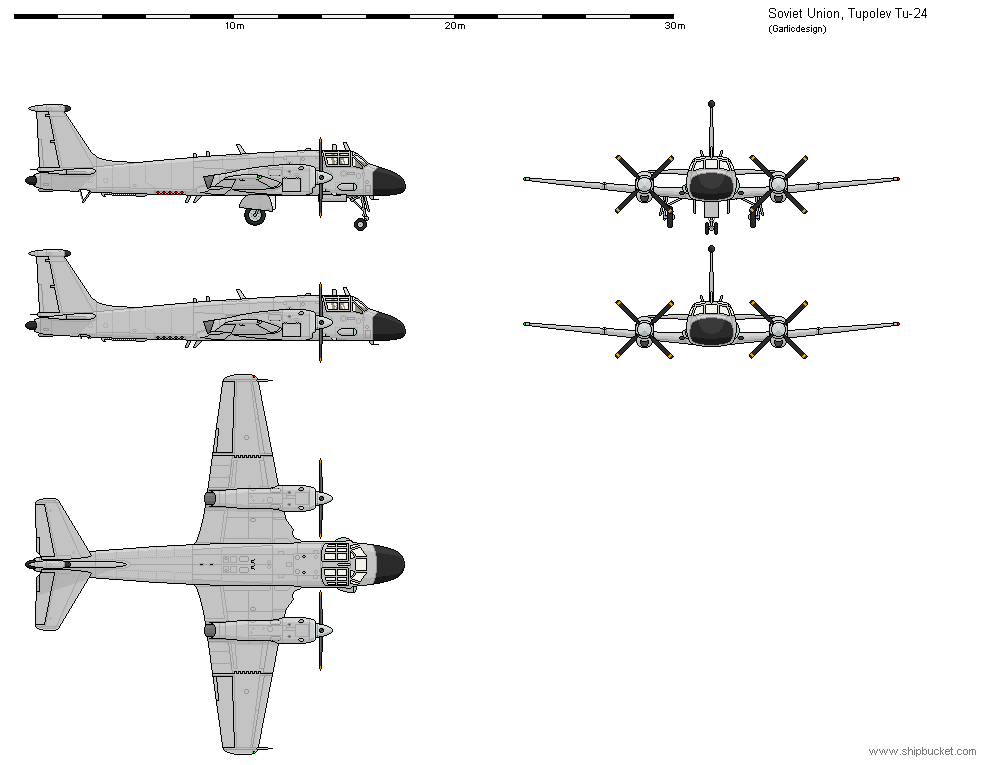

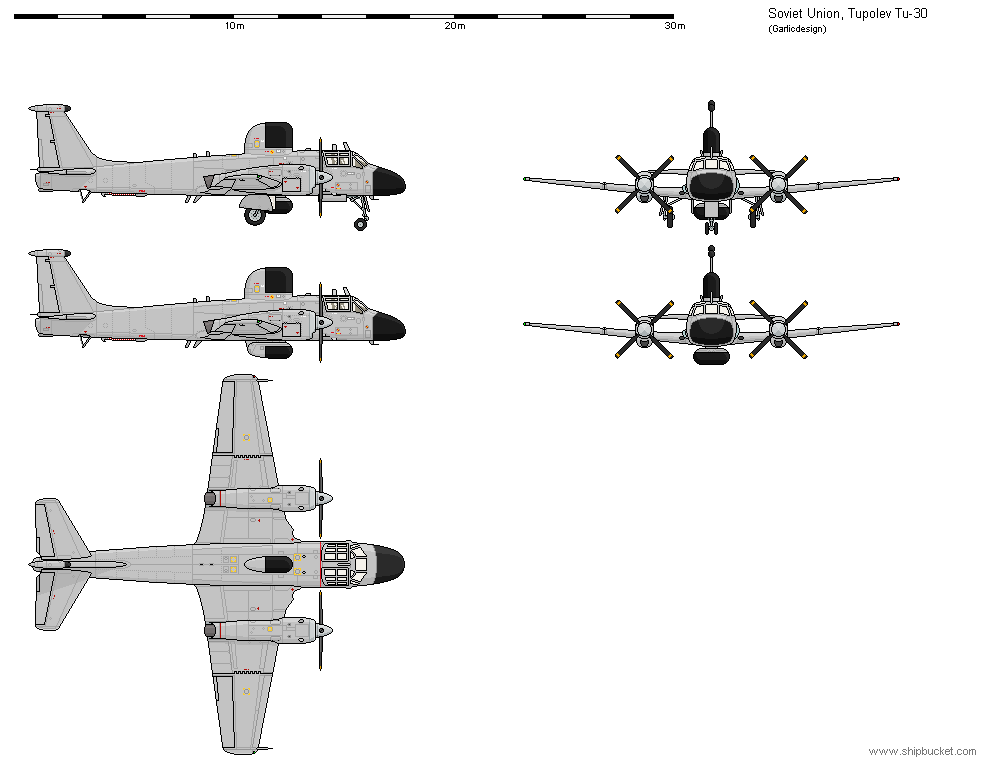

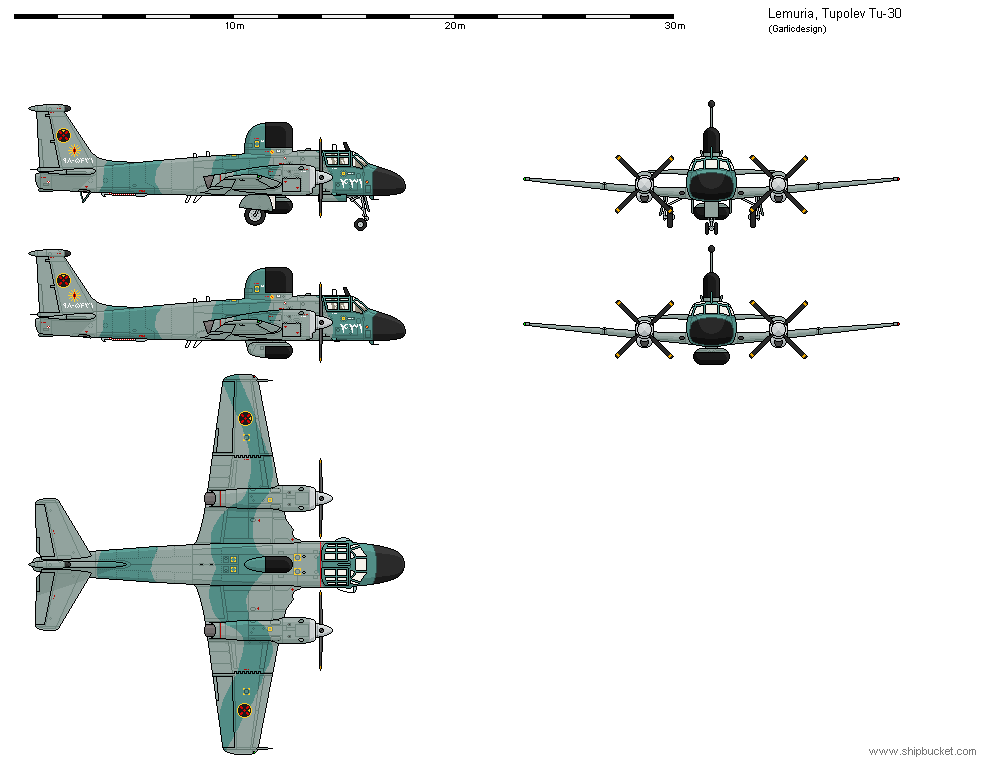

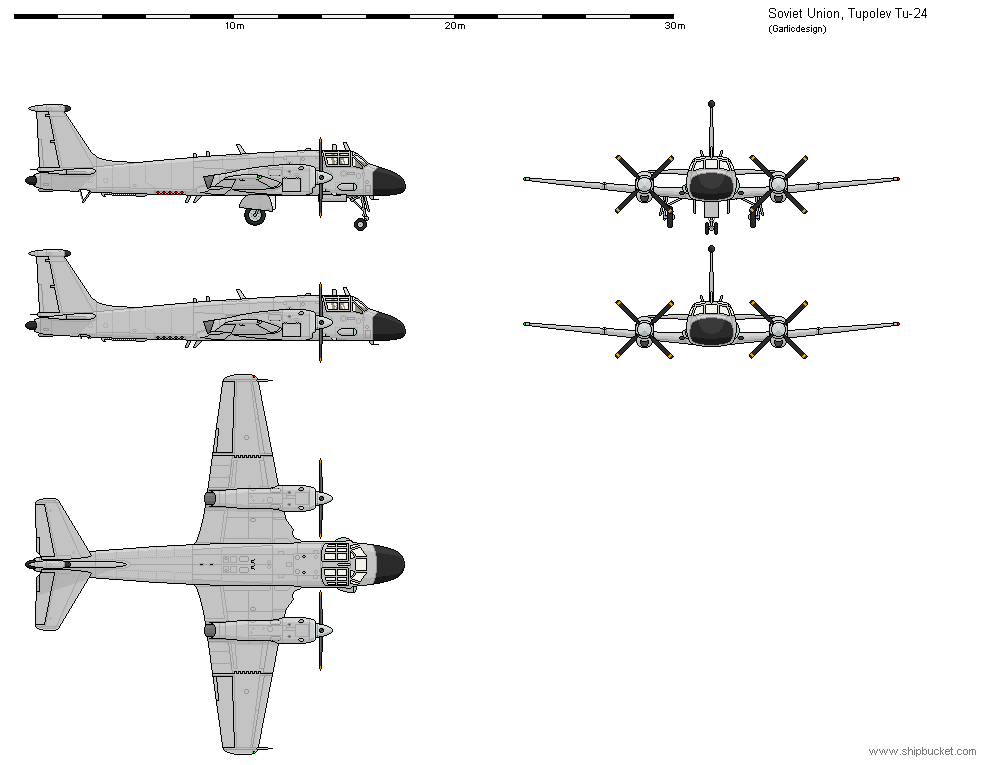

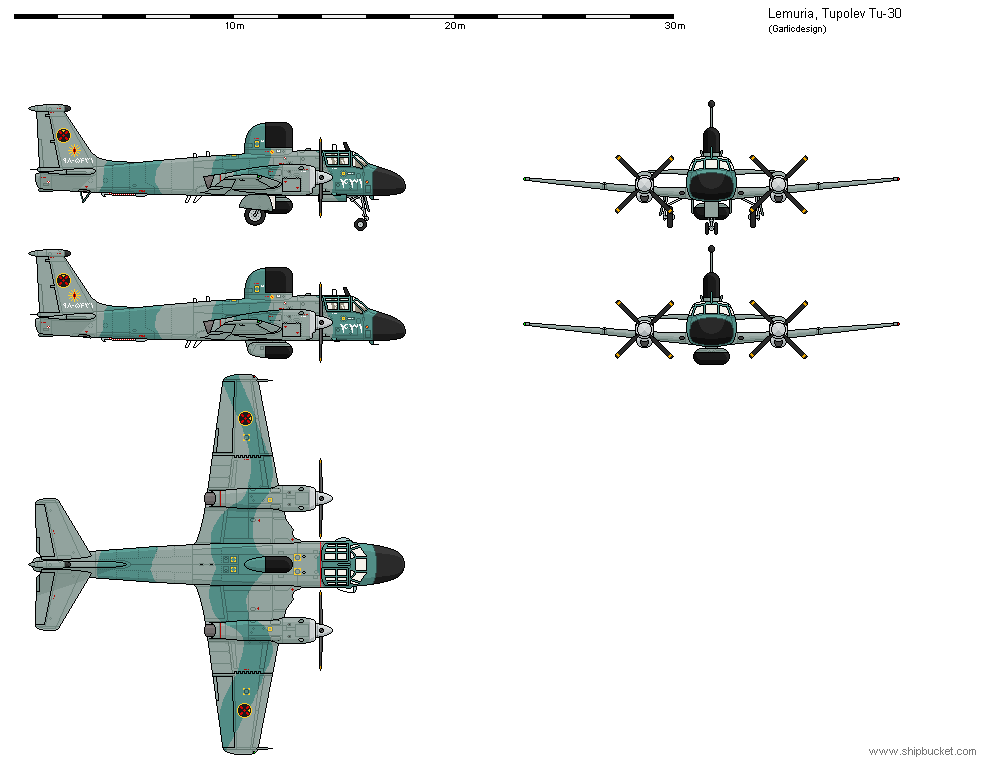

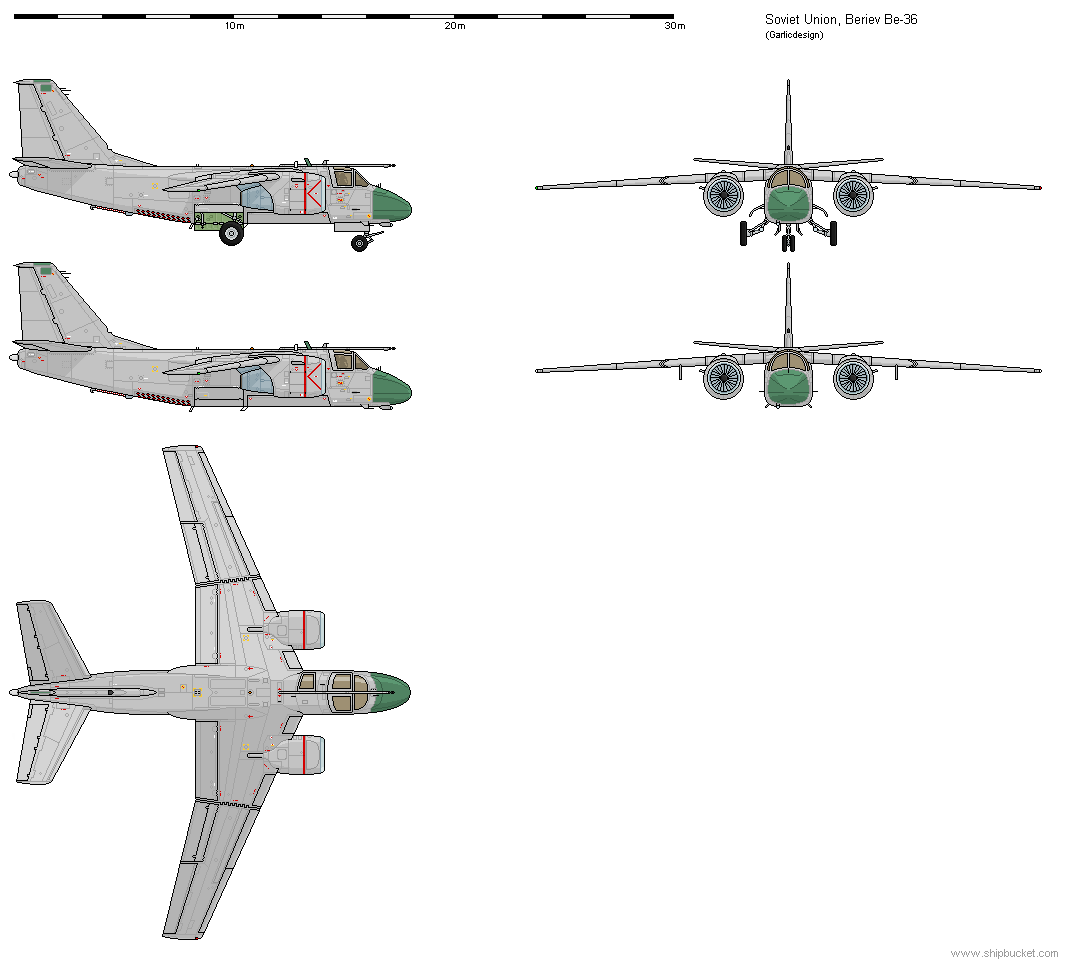

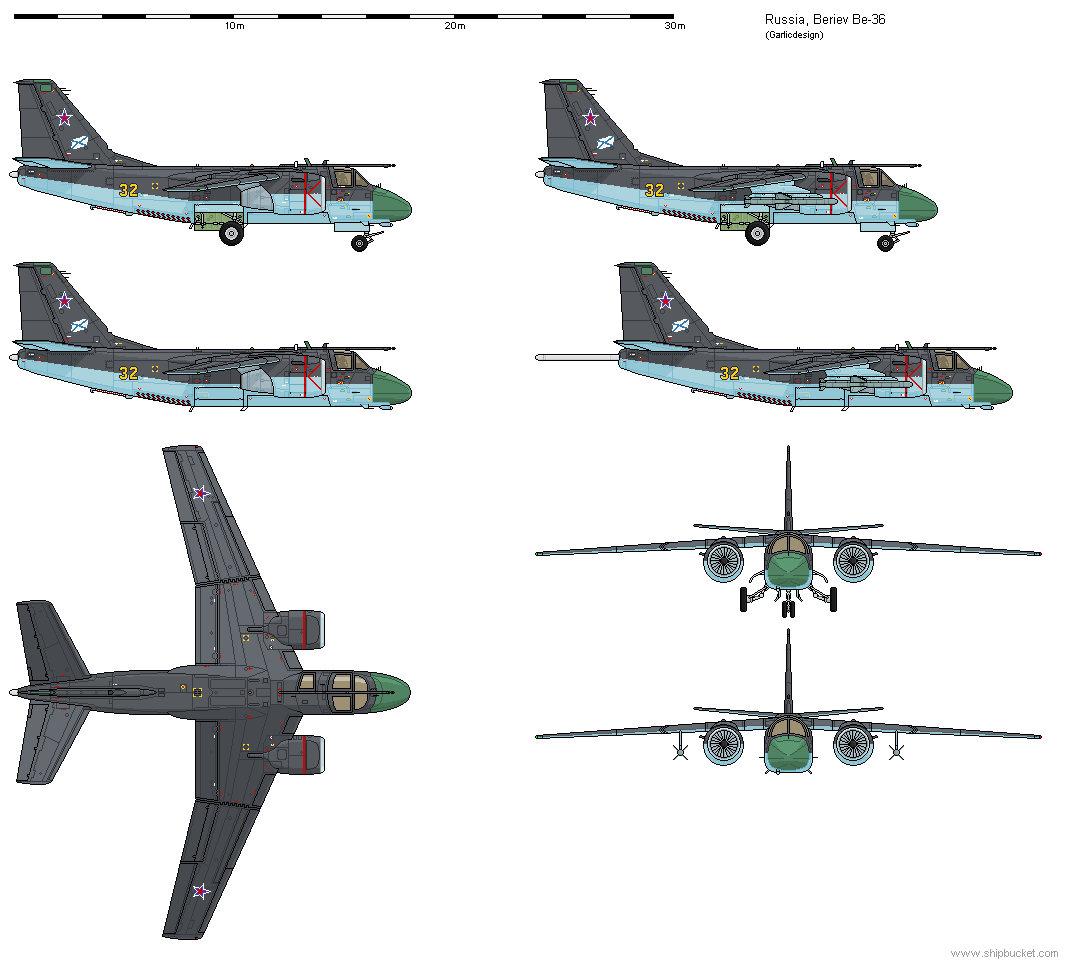

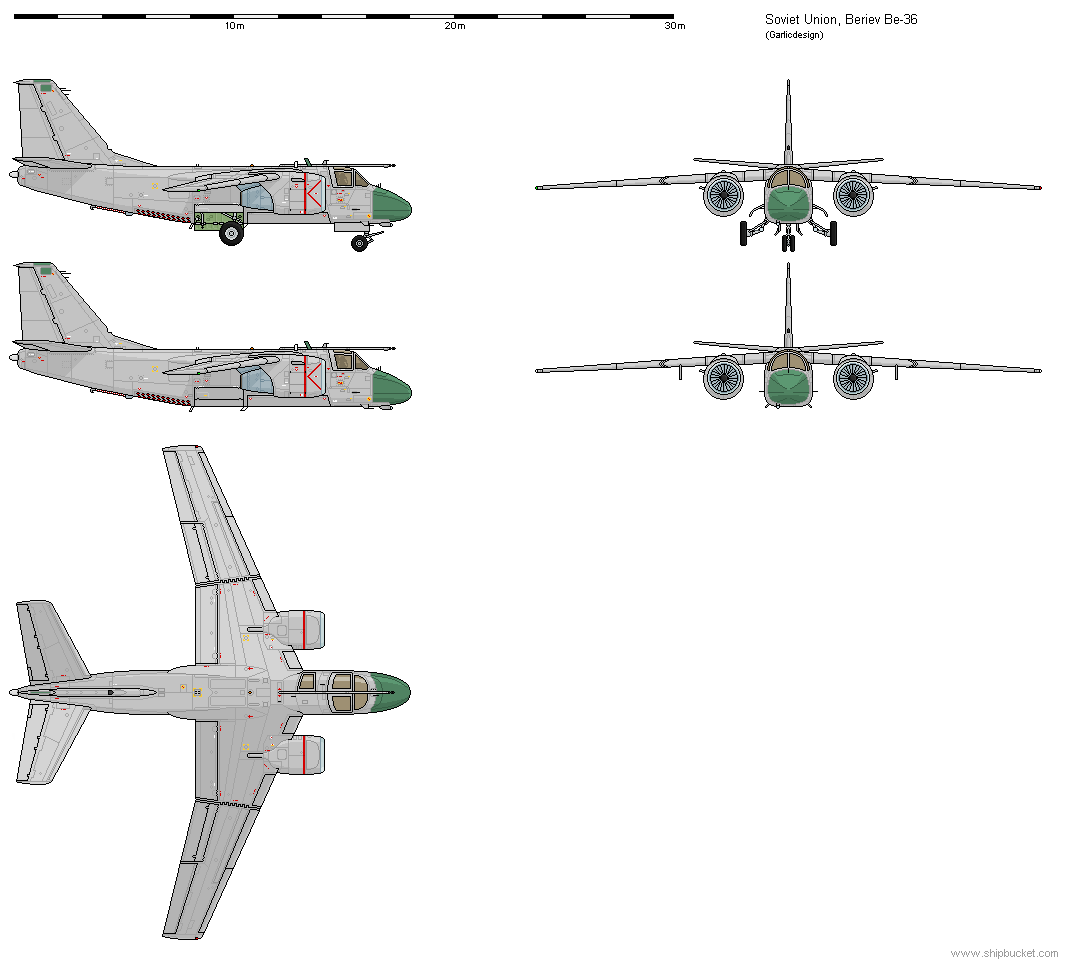

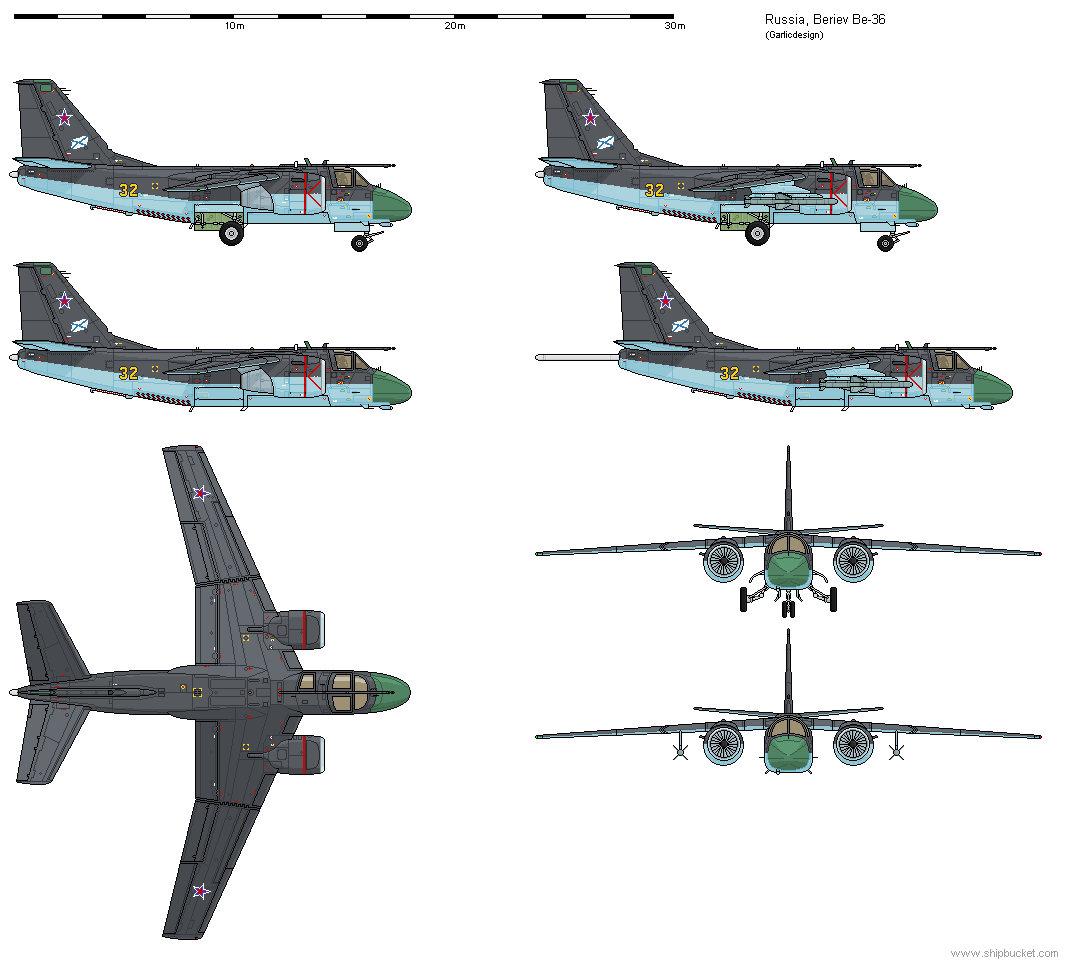

3.1. Tupolev Tu-24/30 ‘Mace/Mirth’

Despite its obsolescence as a strike aircraft, the Tu-18 was a sound and sturdy design which had already been adapted as a makeshift antisubmarine patrol aircraft. The roomy hull was considered highly suitable for further development to a dedicated ASW platform, and since the ASW role had been added to the portfolio of the Soviet carrier fleet, Tupolev was asked to modify the Tu-91 accordingly. The result was a plane with the OKB designator Tu-145 whose prototype was presented in 1973. The bow-mounted turboprop was replaced with two Ivchenko AI-24s in the wings; at 2.850 shp each, total power was lower than Tu-91’s, as high speed was no longer a requirement. Top speed now was 575 km/h. Fixed gun armament was deleted. The bow was freed for a powerful surface search radar capable of picking up very small targets such as periscopes, or larger targets at very long ranges; without the shaft running straight through the cockpit, a third crewmember could be accommodated on the centerline, serving as a weapons and sensors operator. In the stern, a MAD probe was installed, and additional passive radar, thermal, wake-tracking and infrared sensors were added in the hull sides and on top of the tailfin. A sonobuoy launch battery was installed into the aft hull. Armament comprised depth charges, 400mm aerial torpedoes, single mounted 240mm and 325mm rockets, and Kh-23 (AS-7) missiles. The total package was a fully up-to-date ASW platform.

Series production was approved late in 1974, and the first production aircraft replaced the decrepit Tu-18 in 1976. The first squadron of nine embarked on Kiev in 1977, and the following Kiev-class carriers carried one squadron each from the beginning. More of the class equipped a dozen coastal antisubmarine squadrons, mostly deployed with the Baltic and the Black Sea fleets, but also to expeditionary units protecting Soviet naval bases abroad in Syria and Vietnam. NATO assigned the reporting name ‘Mace’.

All Tu-24s could be fitted with a buddy refueling drum, and were used in this capacity at least as frequently and intensely as in their primary ASW function. Production continued till 1983, and a total of 272 units of the basic ASW variant were built. They delivered sterling service for almost a quarter century. Most received a mid-life upgrade with totally revamped electronics and provisions for Kh-25 (AS-10) missiles.

The airframes were beginning to show signs of age since 1995, and replacement with the Beriev Be-36 – scheduled to begin in 1996 – was delayed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and was not completed before 2010.

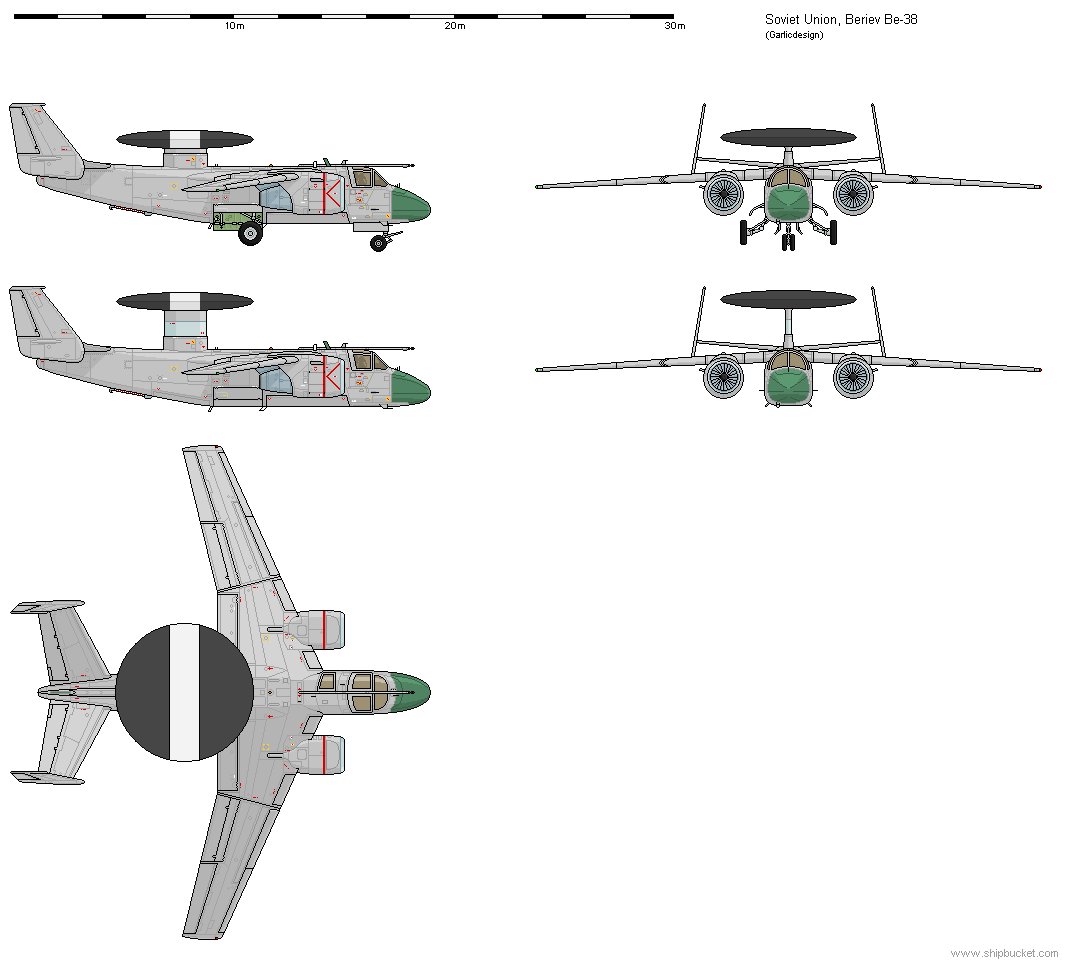

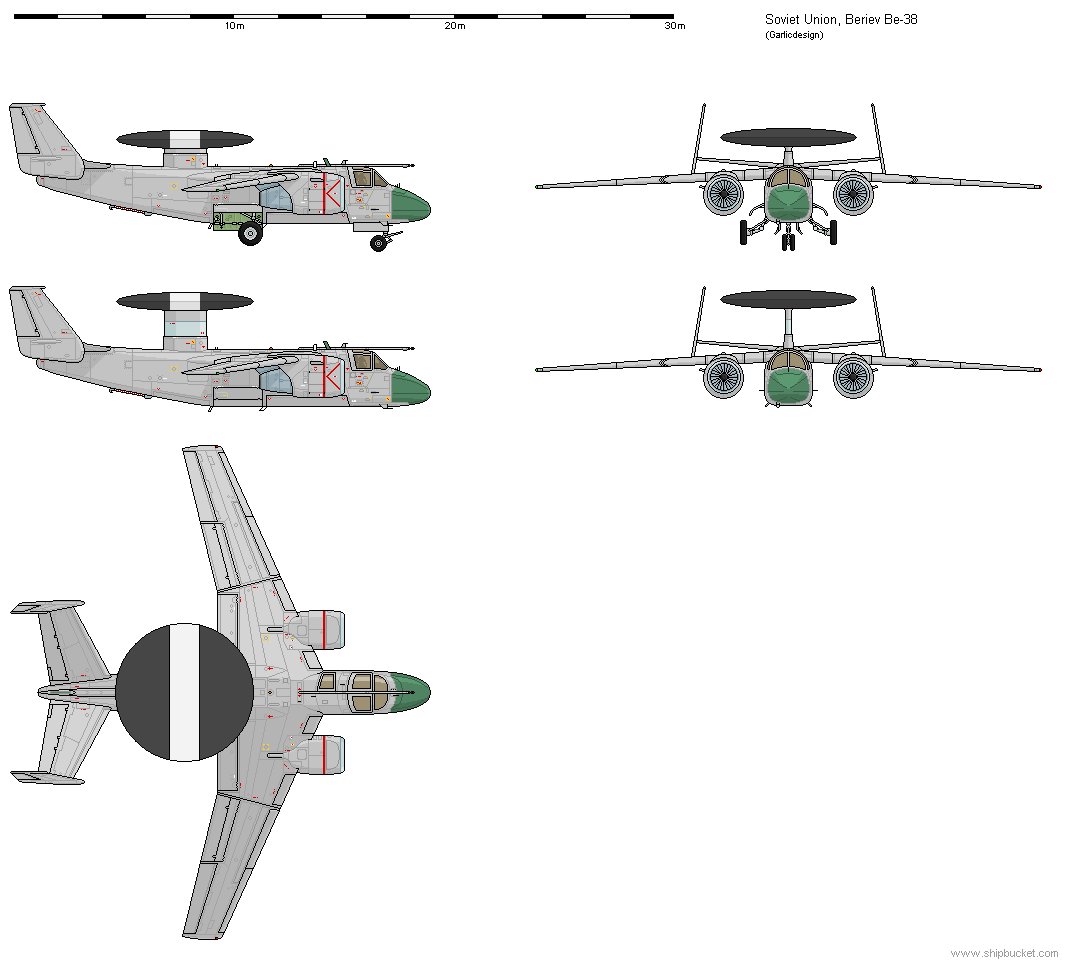

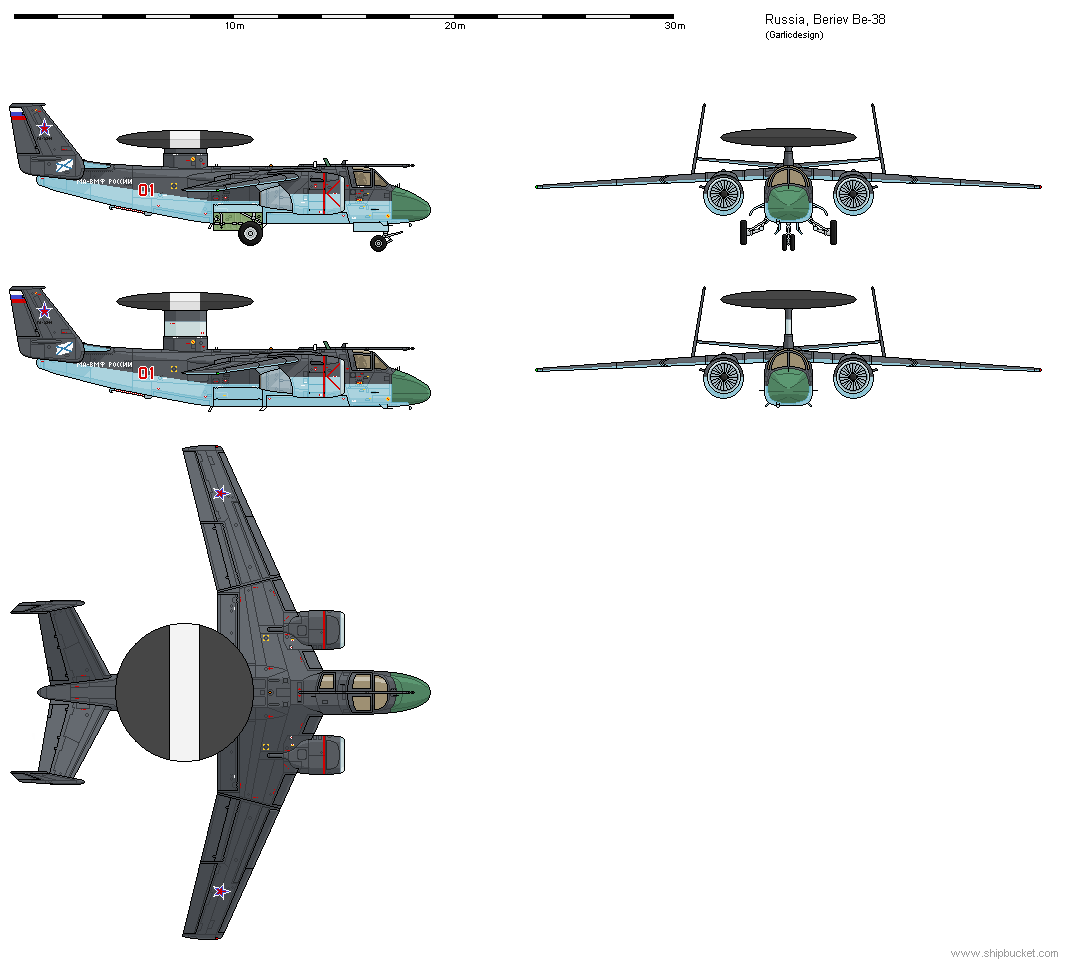

By the time the Tu-24 was approaching operational status, acquisition of a carrierborne AEW platform was being given serious consideration. The Soviets at that time already had a rotodome mounted radar named Shmel – installed in the Tu-126 – but that one was large and heavy and could not be adequately miniaturized. On the other hand, a radar system similar to the one installed in the British Walrus (HS P.139B) for the Beriev Be-38 was under development. That two-part radar – code named Rasvet – was available for tests in 1978, when the Be-38 project was frozen when KGB found out the Beriev OKB to be infested with Thiarian spies. The Rasvet radar was the only part of the project not compromised, and it was decided to mount it in a modified Tu-24 as a stopgap measure. It soon became apparent it was not possible to mount it fore and aft in the Tu-24 because of structural limitations of the airframe. It could however be made to work if placed close to the centre of gravity, in a fashion similar to the vintage US EC-121, with one radome on top of the aircraft and the other one below. In this configuration, the first Tu-45 AEW variant took to the air in 1980. It received the service designator Tu-30. Tests showed the Rasvet radar was still far from mature, although the vertical arrangement worked better than the original horizontal one. It took two more years to get the Tu-30 operational, although the Rasvet was still a far cry from the contemporary US APS-125 performance-wise.

From 1983, a batch of 18 machines was delivered; by 1987, all four Russian frontline carriers embarked a flight of three. NATO called the type Mirth. The older Moskva and Leningrad were relegated to second line duties after 1985 and never received AEW platforms.

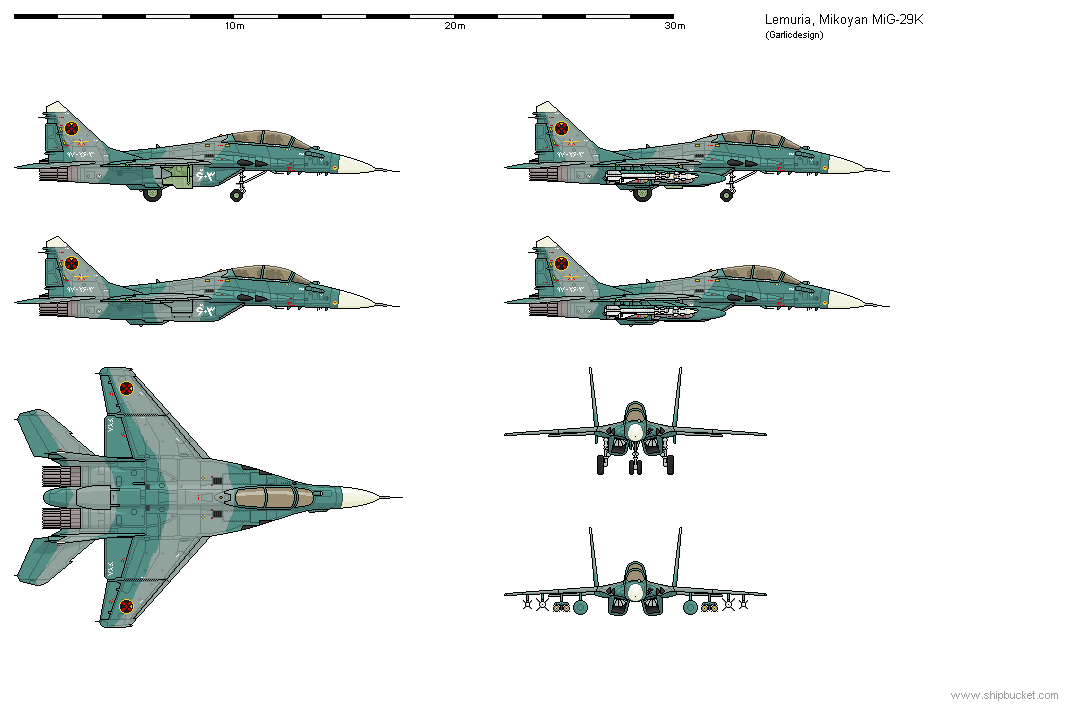

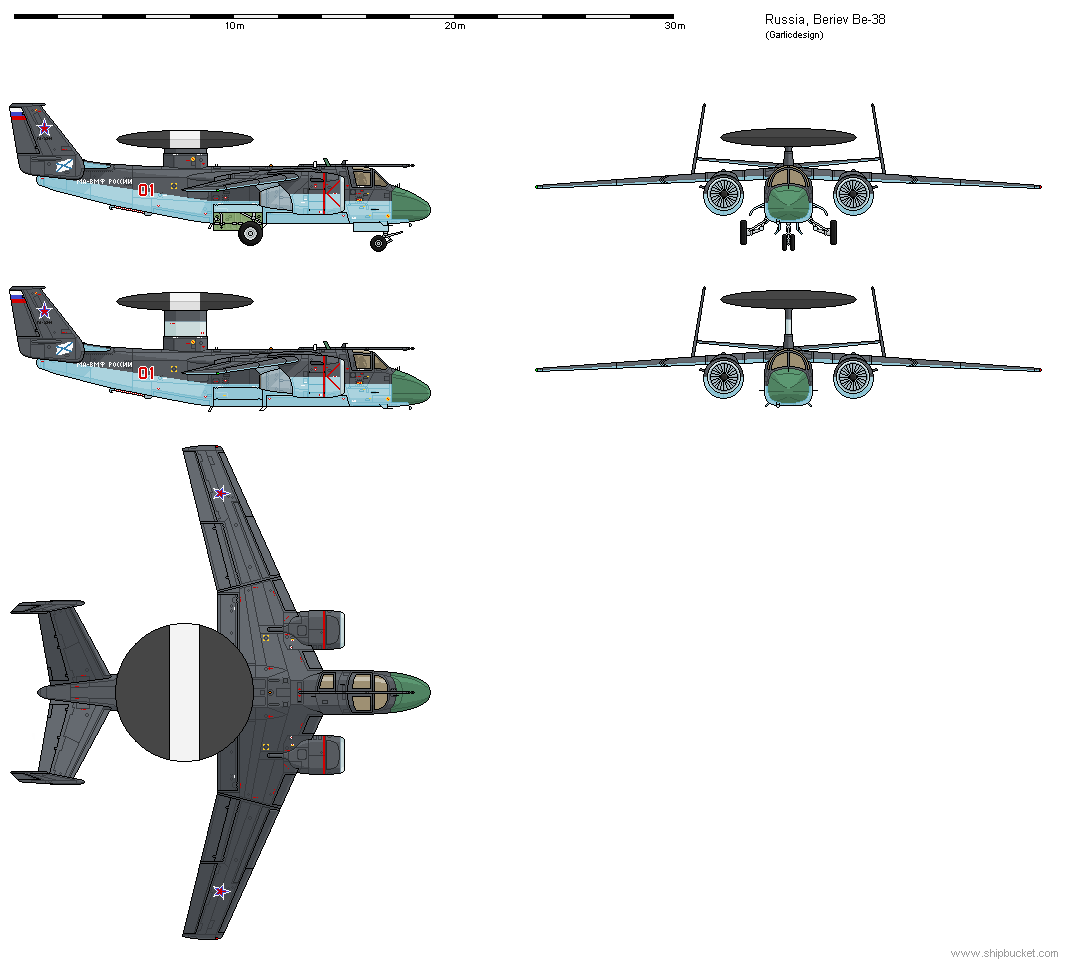

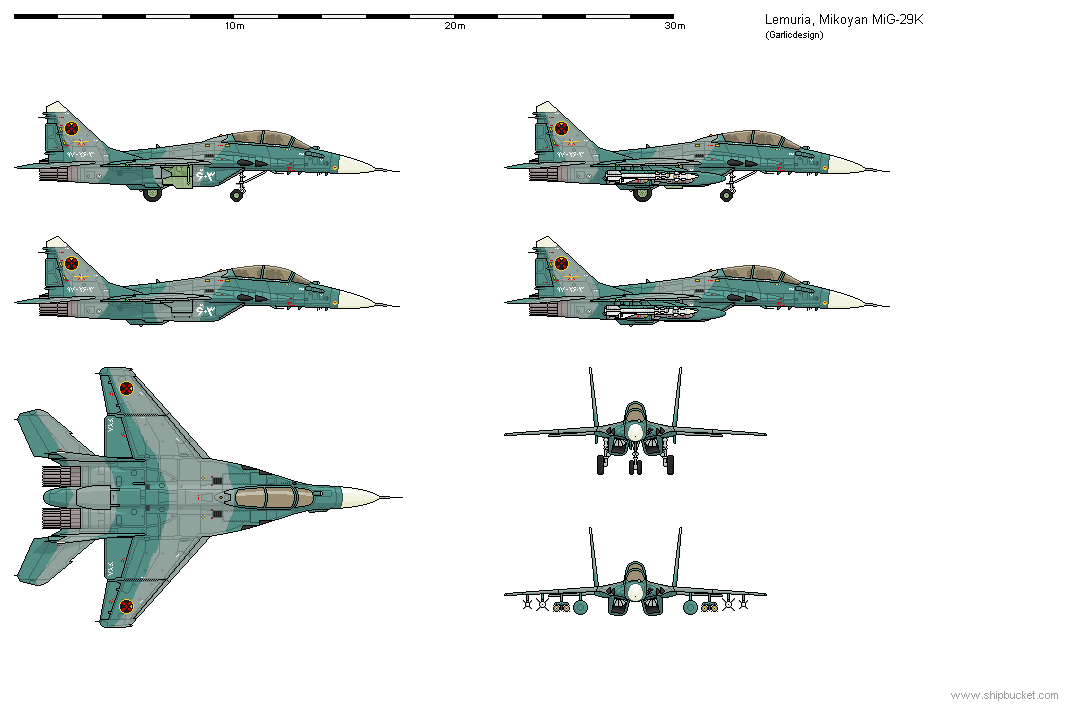

The Tu-30 and its Rasvet radar was plagued by persistent performance and reliability issues throughout its career; its value was more of a symbolic nature, particularly because NATO did not know how bad it really was. In the late 1980s, the Be-36/38 project, which was still considered state of the art, was revived, and the AEW version was given top priority. When Be-38 became available in 1994, the Tu-30 was retired in a hurry. 15 remaining airframes were sold to the Lemurian Navy, along with two Kiev-class carriers and a hundred new MiG-29Ks, in 1998.

The Lemurians had little fun with their Tu-30s, because when they were fully operational in 2000, their neighbours were fully informed about its performance, or rather the lack thereof. Poor relations with anyone capable of supplying a replacement forced the Lemurians to operate the Tu-30 for twenty years; the Be-38 was not cleared for export prior to 2010, and negotiations were terminated in 2013 in favour of purchasing the Chinese KJ-600. This machine became operational in 2015, and Lemuria was the launch export customer, receiving a dozen between 2018 and 2020. The Tu-30 was finally retired late in 2019.

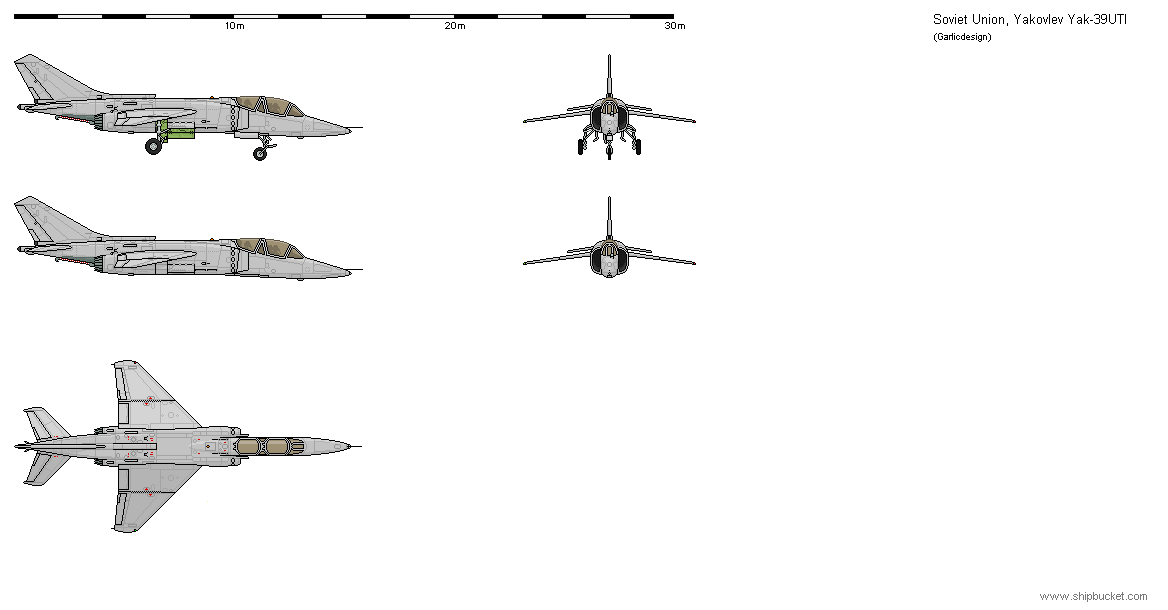

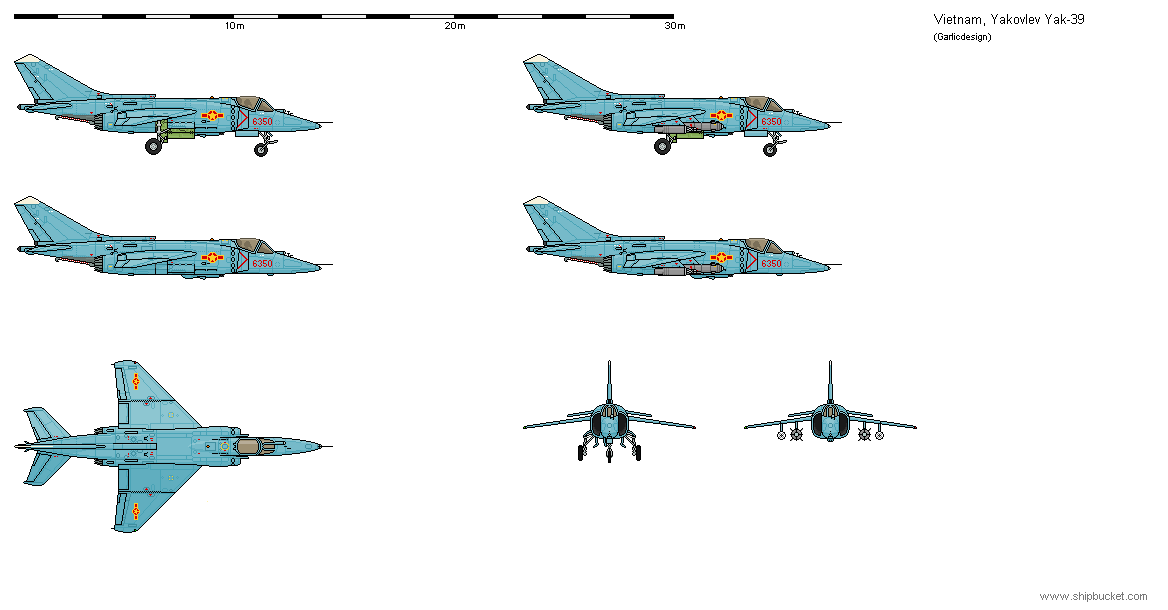

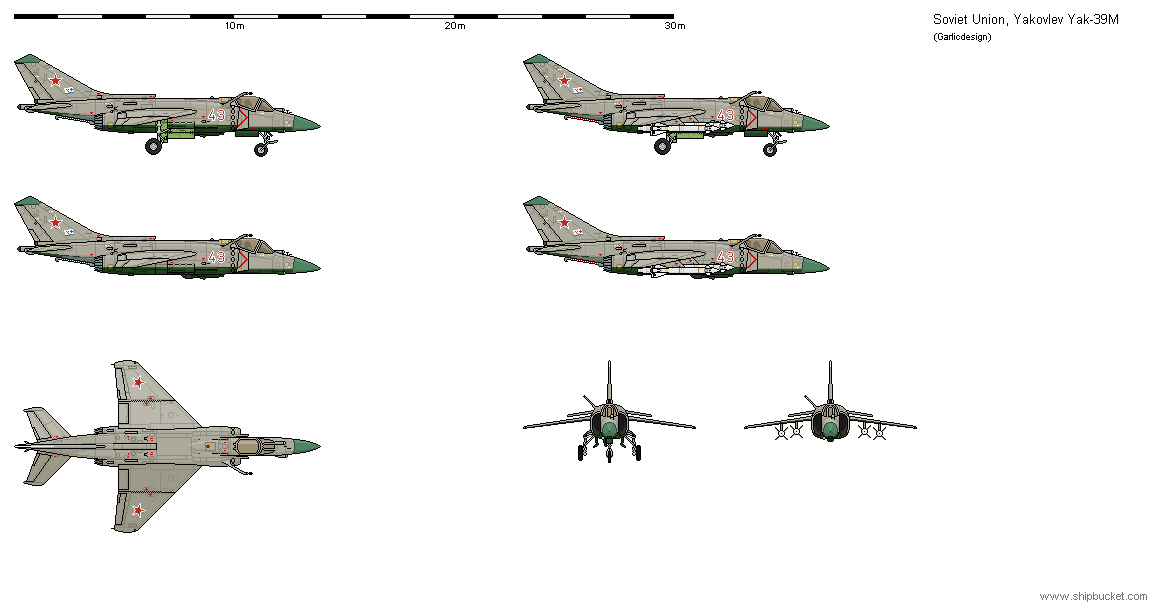

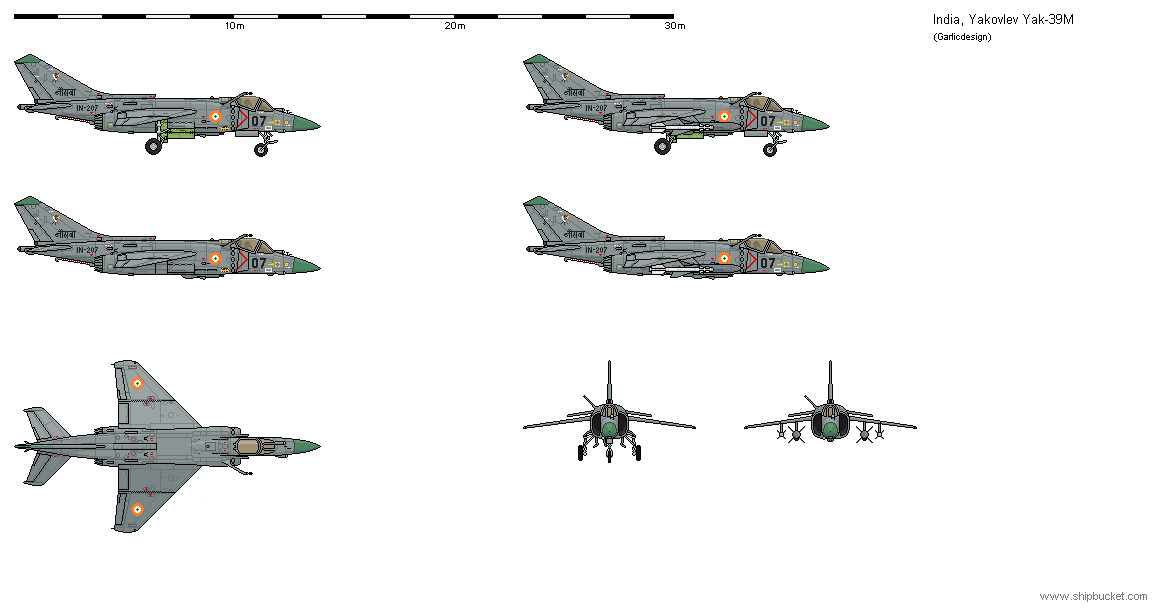

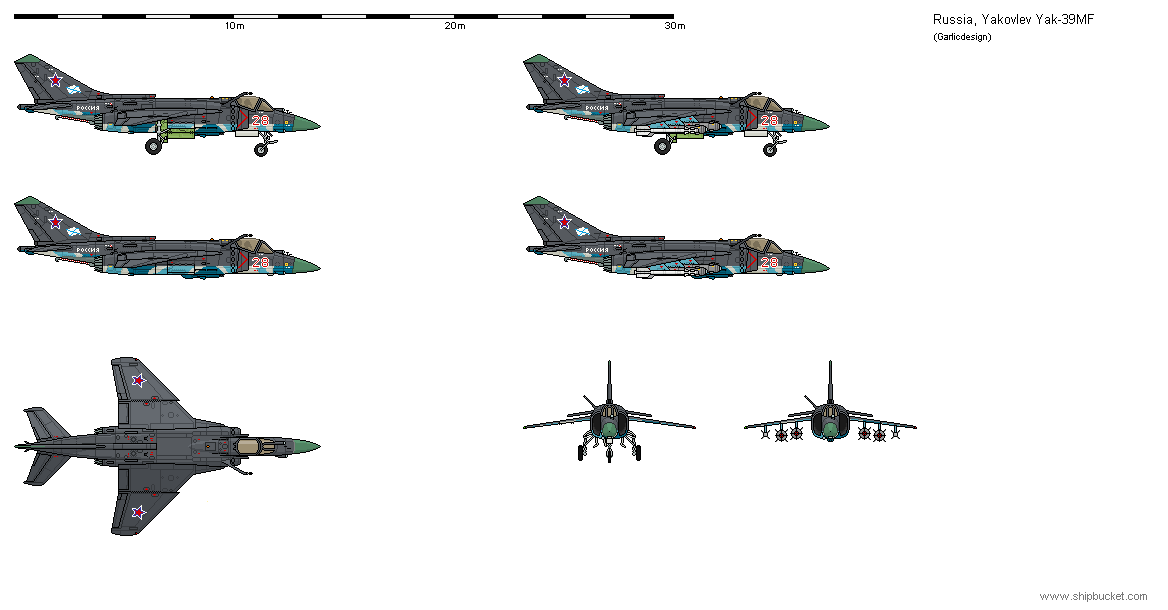

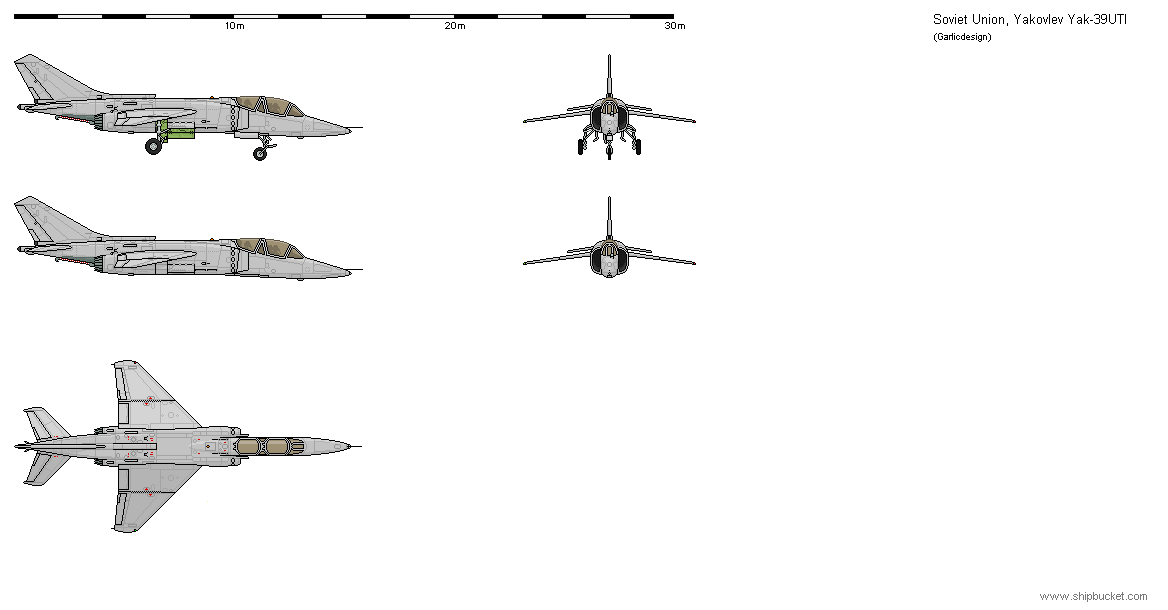

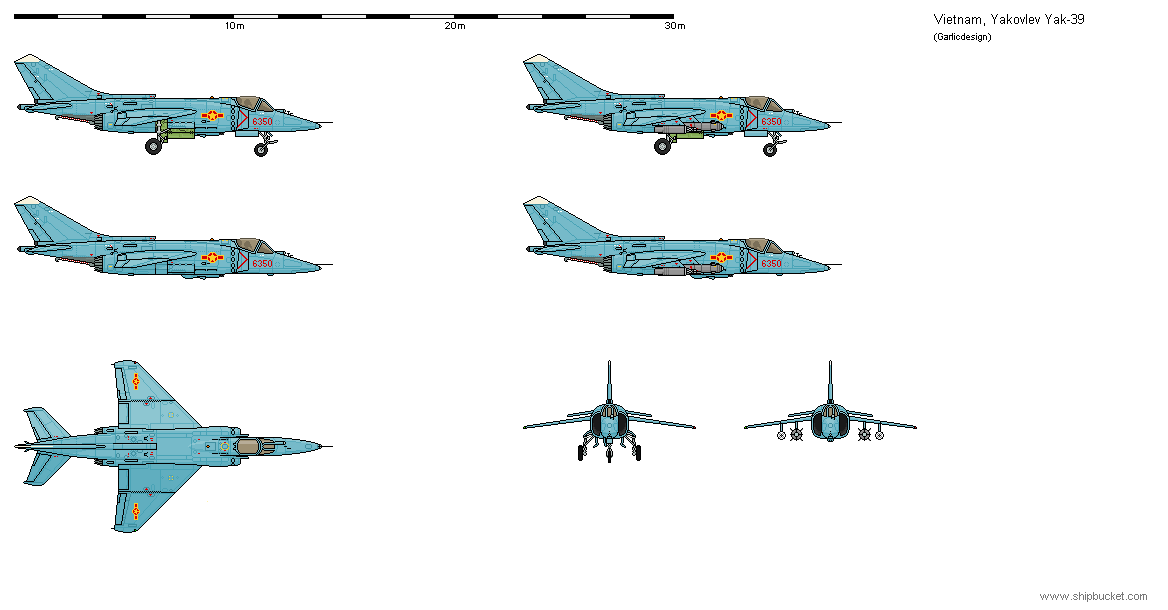

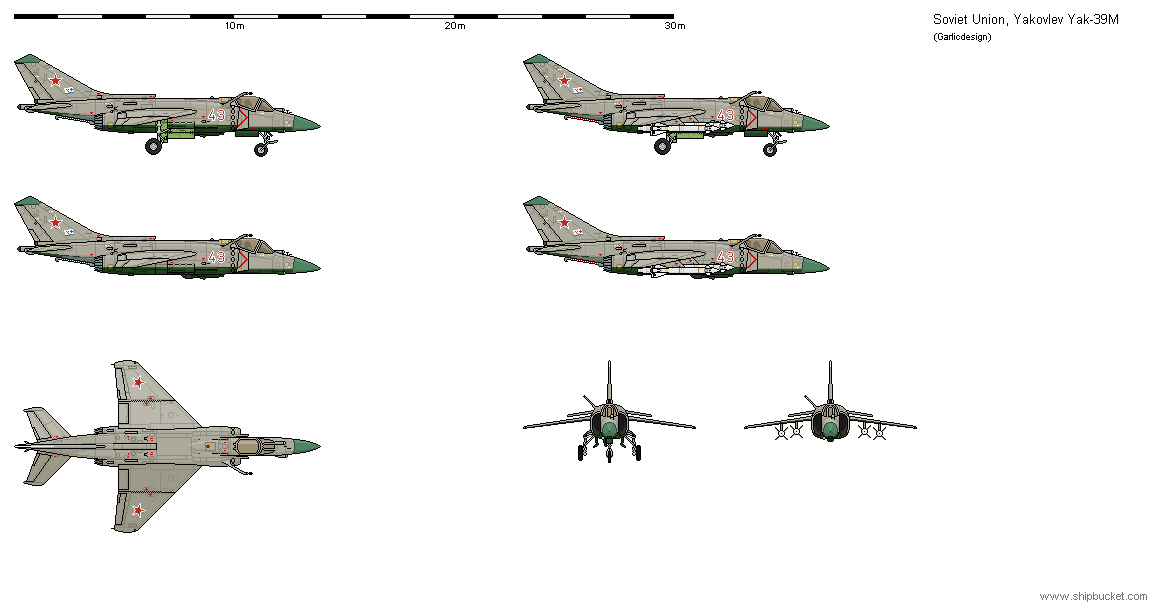

3.2. Yakovlev Yak-39 ‘Fungus/Mushroom’

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Yakovlev built a series of unsuccessful VTOL designs, culminating in the Yak-38 of 1974. Their main problem was that the Navy, for which they were designed, did not want any, because they feared the CTOL carrier programme might be cut short in favour of less capable, but also less costly aviation cruisers embarking a dozen second-rate planes at best. In a rare instance of initiative, Yakovlev tried to salvage the design by converting it to a CTOL trainer aircraft to replace the Yak-31 UTI, with a single-seat light strike derivative for export as an afterthought. Both designs received the OKB designator Yak-120. The plane resembled the VTOL Yak-38, but had a shorter hull (no space for lift engines needed) and wider wings providing good low speed flight characteristics. Power was provided by two Ivchenko AI-25FR turbofans, a reheated version of the standard AI-25 which delivered 18.5 KN dry and had an afterburner for 27 KN wet thrust. At an empty weight of 4.700 kilograms, the Yak-120 had ample internal fuel stowage and four hard points each cleared for 800 kilograms payload; a twin 23mm autocannon was mounted beneath the belly. Flight tests in 1976 proved great agility and excellent low altitude characteristics, with a top speed of 1.200 kph (Mach 0.95); at altitude, the plane was transonic, capable of 1.400 kph (Mach 1.3). It was the first Soviet combat aircraft with fuel-efficient turbofan engines, and with full external payload, a radius of action of 800 km was attained, almost as much as the much larger Yak-34, whose payload was only 20% bigger. The Yak-120 had a navigation radar, FLIR, IRST and a combined internal laser rangefinder/designator; it could employ the full range of Soviet air-to-ground ordnance without having to use external targeting pods.

The trainer version had a longer nose, with the seats in a staggered arrangement to improve view from the aft seat; it was the first Soviet trainer with this feature. It lacked the internal cannon.

Although the AVMF had no real requirement, the Yak-120’s simplicity and compact size – an important factor for carrier aviation – made it an attractive choice. By substituting one Yak-34 squadron per carrier with two squadrons of the new plane, air group size of a Kiev-class ship could be increased to 65, at very little loss in capability per plane. Additionally, the Yak-34 was neither designed for nor very good at low altitude penetration missions; the smaller Yak-120 could fly low-low-low mission profiles and evade much of NATO’s defensive measures, which were tailor-made to counter high-altitude saturation strikes. Based on these considerations, the Yak-120 was commissioned as Yak-39 in 1977, and 150 machines (including 50 trainers) were ordered to supplement the Yak-34 and start replacing the Yak-31 UTI. Deliveries were processed in 1978 and 1979. When NATO became aware of the type, it received the less than flattering reporting name Fungus.

The planes were instantly popular, and a follow-on order of 150 – half of them trainers – was issued in 1979, to be delivered between 1980 and 1982. To remain in theme, the trainer version was assigned the NATO reporting name Mushroom.

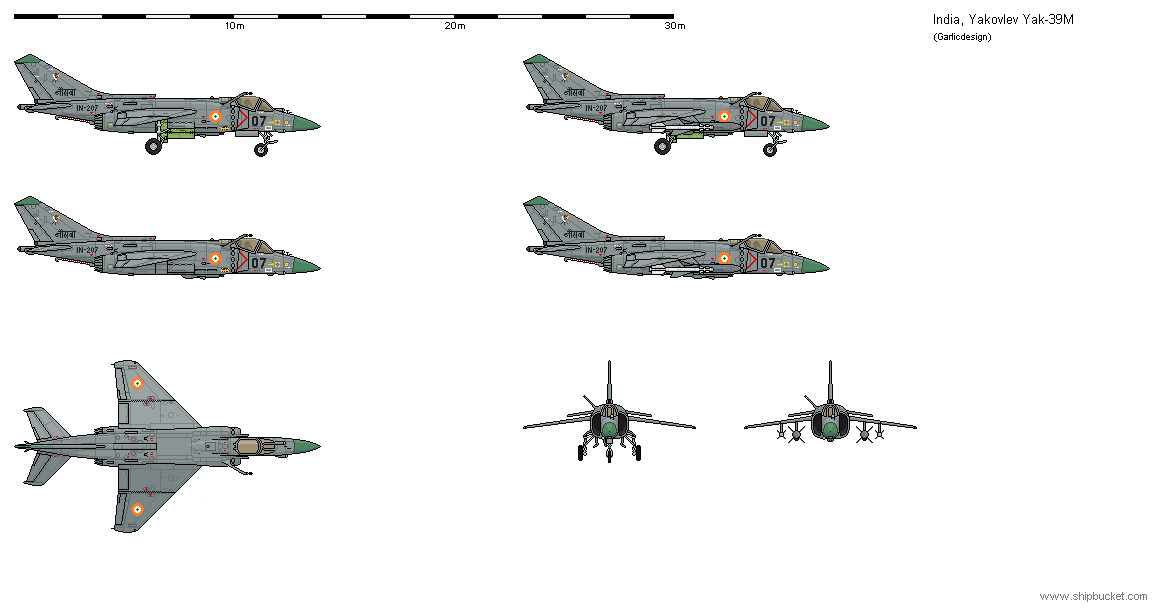

The Soviet Union was no traditional exporter of carrierborne aircraft, but the Yak-39 attracted interest of the Indian Navy, which considered it an ideal choice for their relatively compact carriers. 75 strike-fighters and 15 trainers were ordered in 1980 and delivered in 1982 and 1983; they replaced the hopelessly outdated Sea Hawks still in use with the Indian fleet in the maritime strike role and were adapted to carry a variety of British-sourced ordnance in addition to Soviet supplied Air-to-Air and Air-to-Ground missiles.

Apart from the Indians, the Soviets had no allies or satellites with aircraft carriers; their traditional export customers considered the Yak-39 insufficiently flashy for the air-to-ground role, preferring the Su-20/22 and MiG-23BM. Yak-39’s concealability and ability to fly very slowly at very low altitudes was considered attractive to the Vietnamese, who considered the plane ideal for providing close support in jungle warfare. They ordered 80 machines (including 15 Yak-39UTI) in 1982, which were delivered in 1984/5.

The final export customer was Cuba, whose air force wanted the Yak-39 for the maritime strike role; their 1984 order for 50 machines (including 10 trainers) was processed in 1986.

Meanwhile the Soviets had found that Yak-39’s airframe offered growth potential for installation of a downgraded and –sized variant of the Sapfir radar; an experimental refit was tested in 1985 and considered successful. 90 airframes were fitted with a modified nose with a radar cone, re-locating the laser designator to the starboard side and the IRST on top of the nose. ECM and avionics were also upgraded. The refit project was launched in 1986 and continued through 1988, yielding the new designator Yak-39M. Most other Yak-39s (of the strike version, a total of 175 had been delivered) were phased out by 1990; 25 were delivered to Cuba to bolster that nation’s inventory that year.

India had 50 of its Yak-39s modified to the Yak-39M standard in 1987/8; they also were adapted to fire British Sea Eagle missiles. None of the other export customers modified their Yak-39s in a similar way.

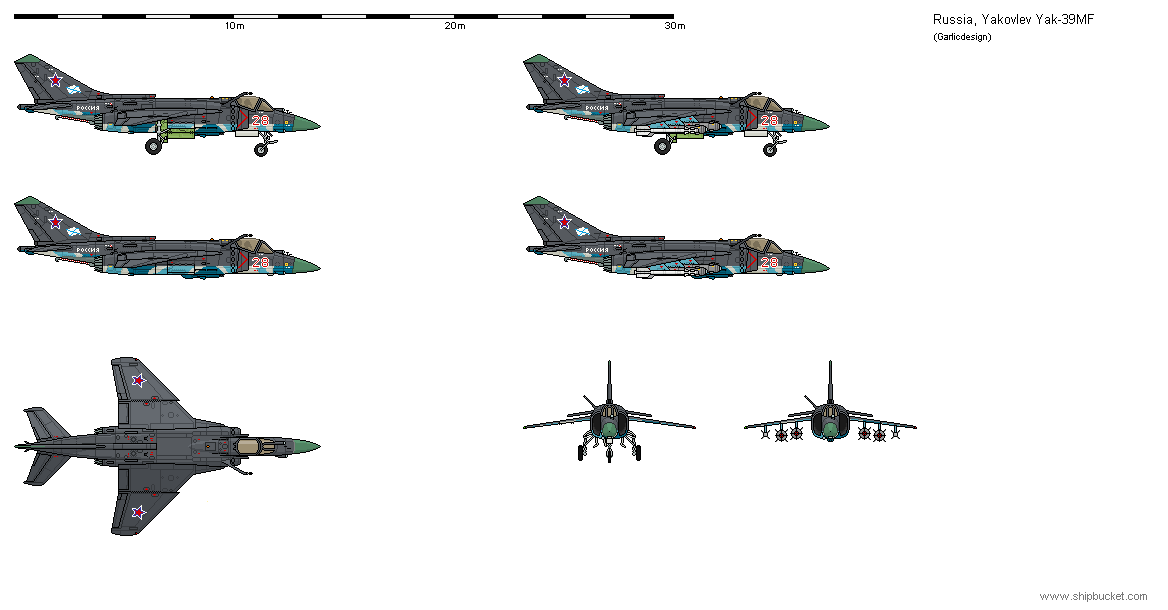

During the late eighties, Yakovlev reworked the basic Yak-39M by replacing the Ivchenko AI-25 with the new Lotarev DV-2R engine developing 24 kN dry and 36 kN at full reheat. The wing was reworked with LERXs and an enlarged outer part; wing fuel capacity was improved by 35%. Speed at optimum altitude increased to 1.700 kph (Mach 1,6) and low-speed characteristics could be further improved. Payload increased to 4.500 kilograms, with two additional hard points under the folding part of the wings. This Yak-39MF version was acquired in 75 copies in 1988/9, supplementing the Yak-39M on the carriers.

With these machines, production was complete at 625 copies, among them 225 trainers. These economic and useful little aircraft had a long service life. The Indians phased them out in 2005 in favour of MiG-29Ks, the Vietnamese in 2015 without replacement, and the Cubans still actively employ the Yak-39 in its most basic variant. The Soviet/Russian Navy retired the Yak-39 in 1990 in favour of the Yak-39MF and the Yak-39M in 2005 without replacement. The Yak-39MF would remain in service till 2015.

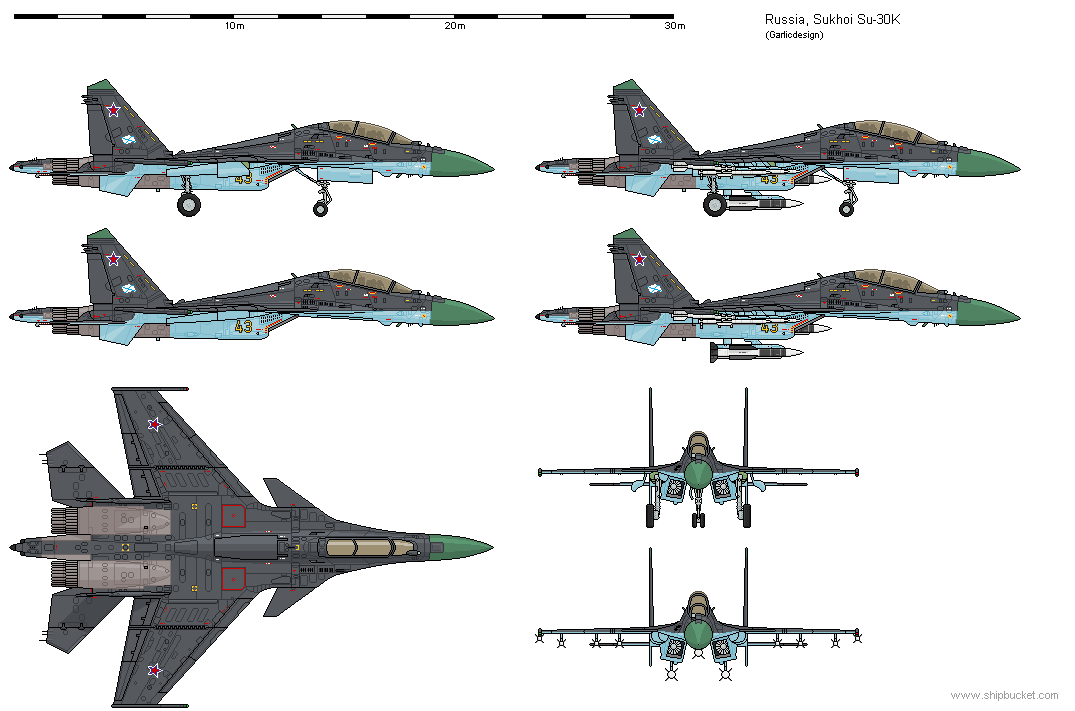

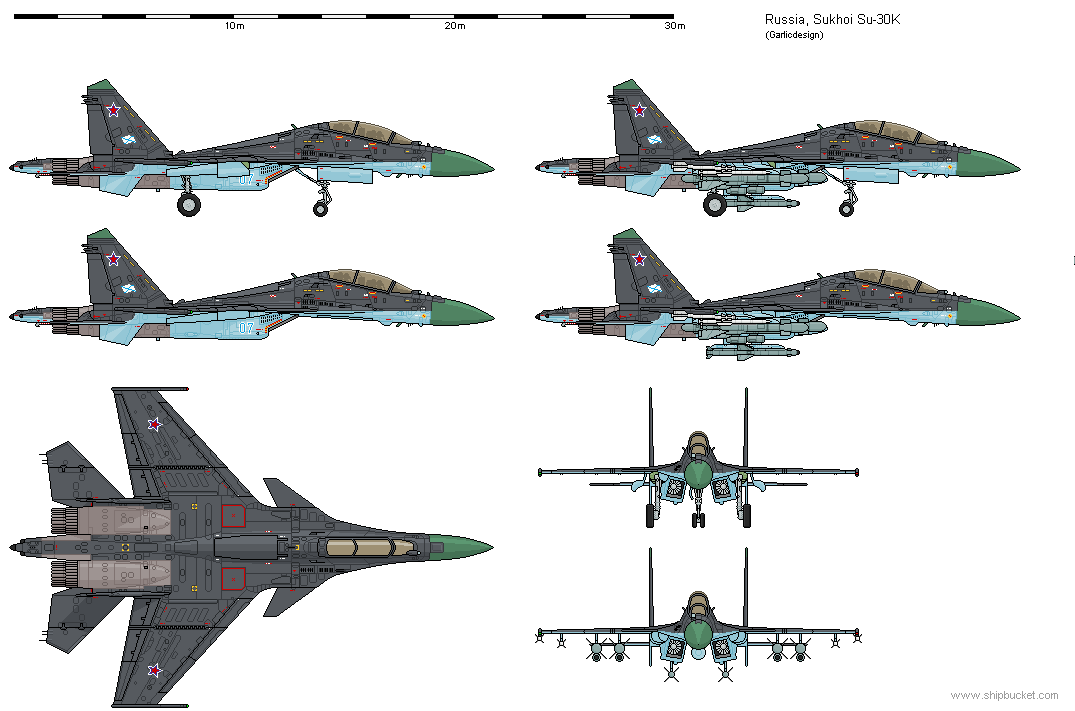

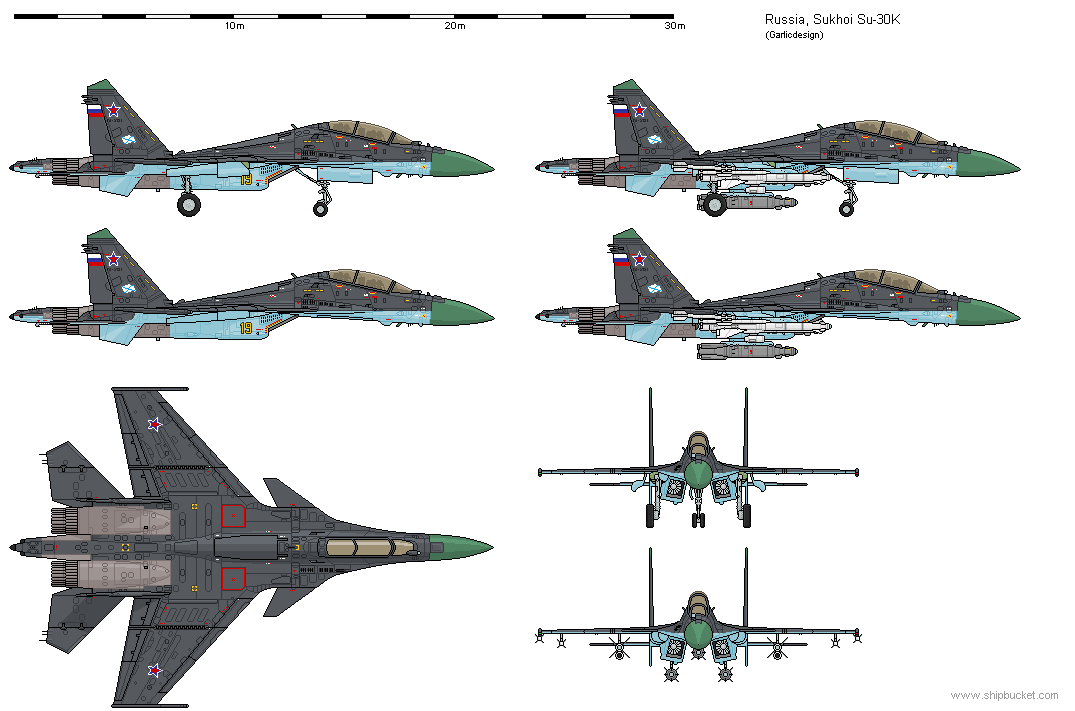

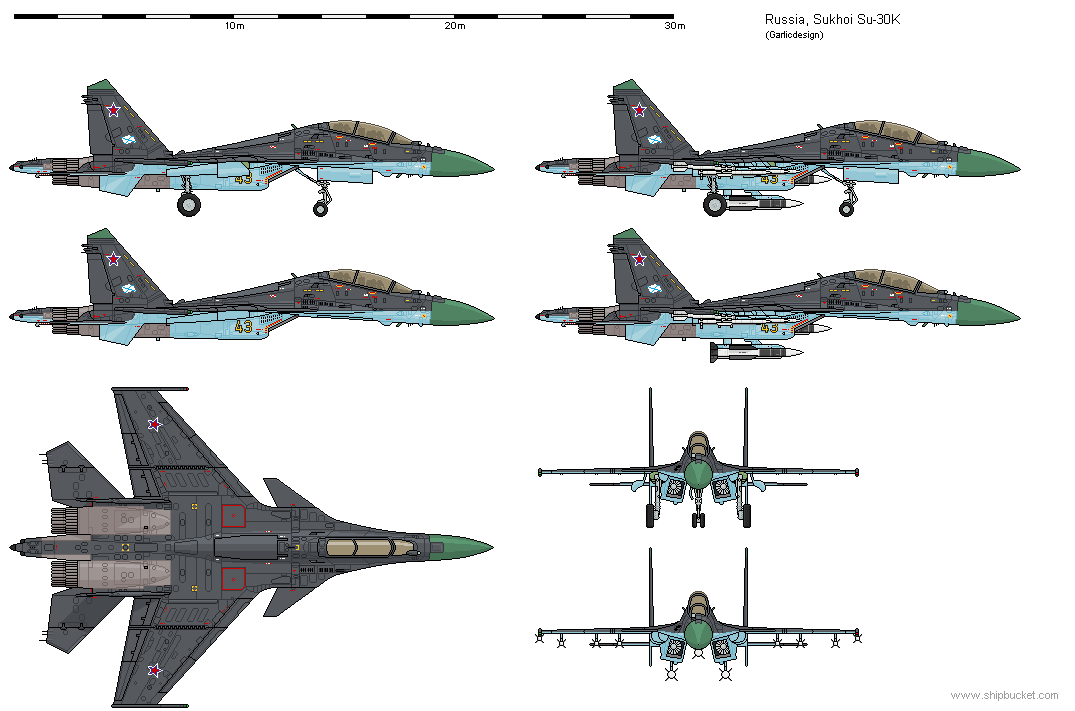

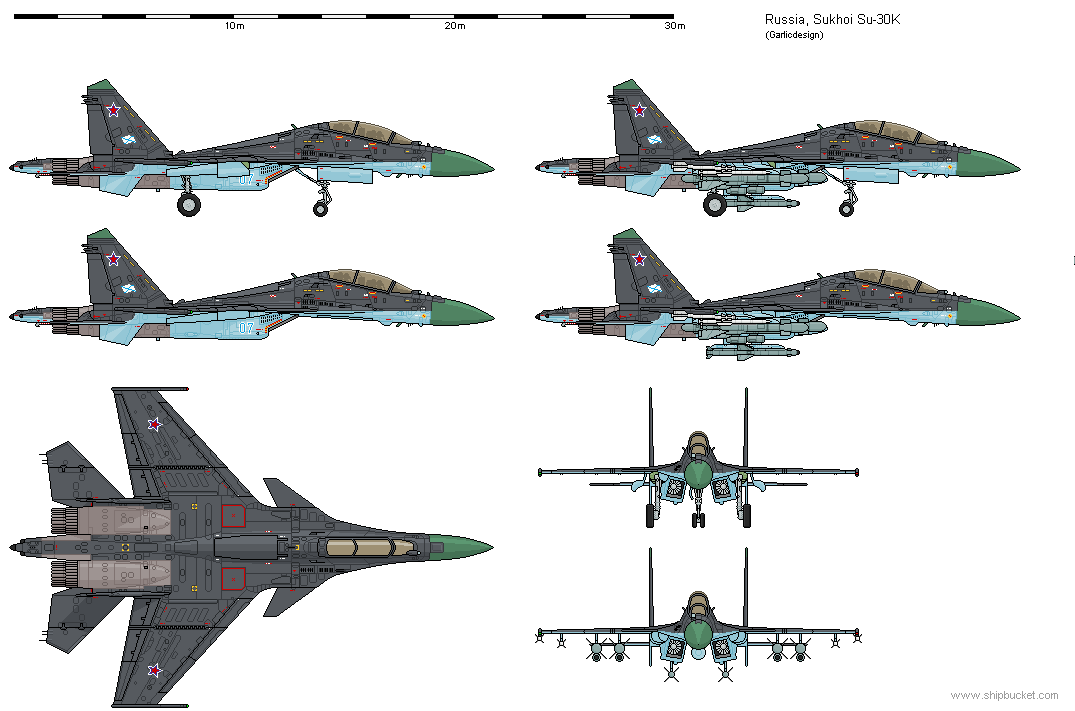

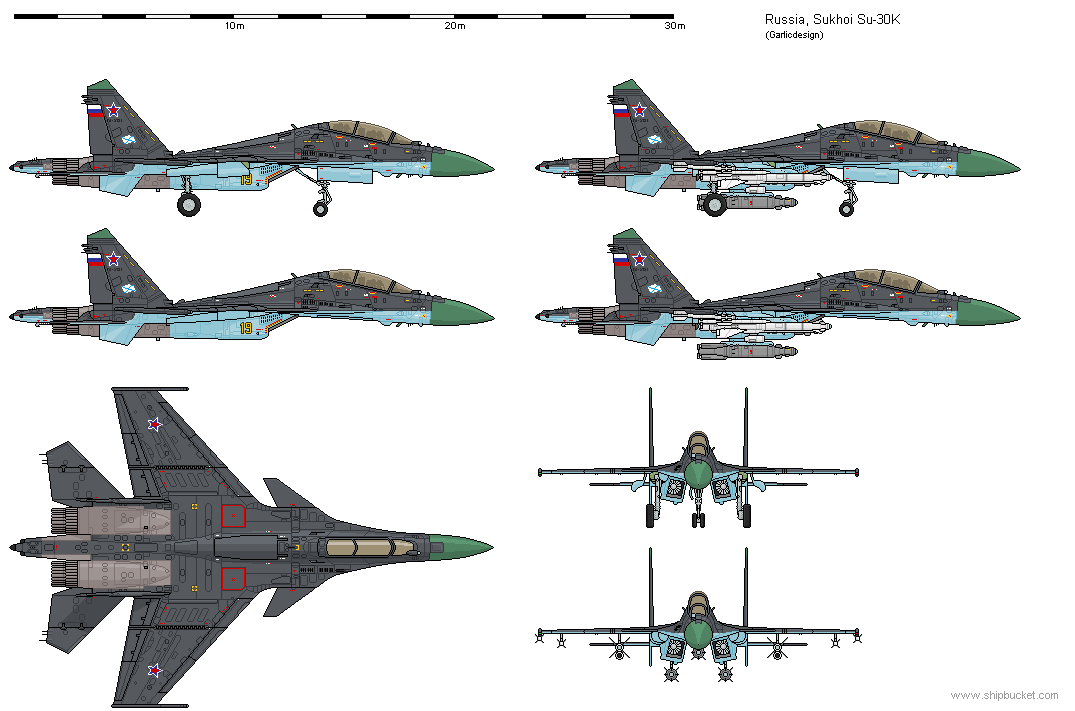

That year, the Yak-39MF in 2015 in favour of the Su-30K.

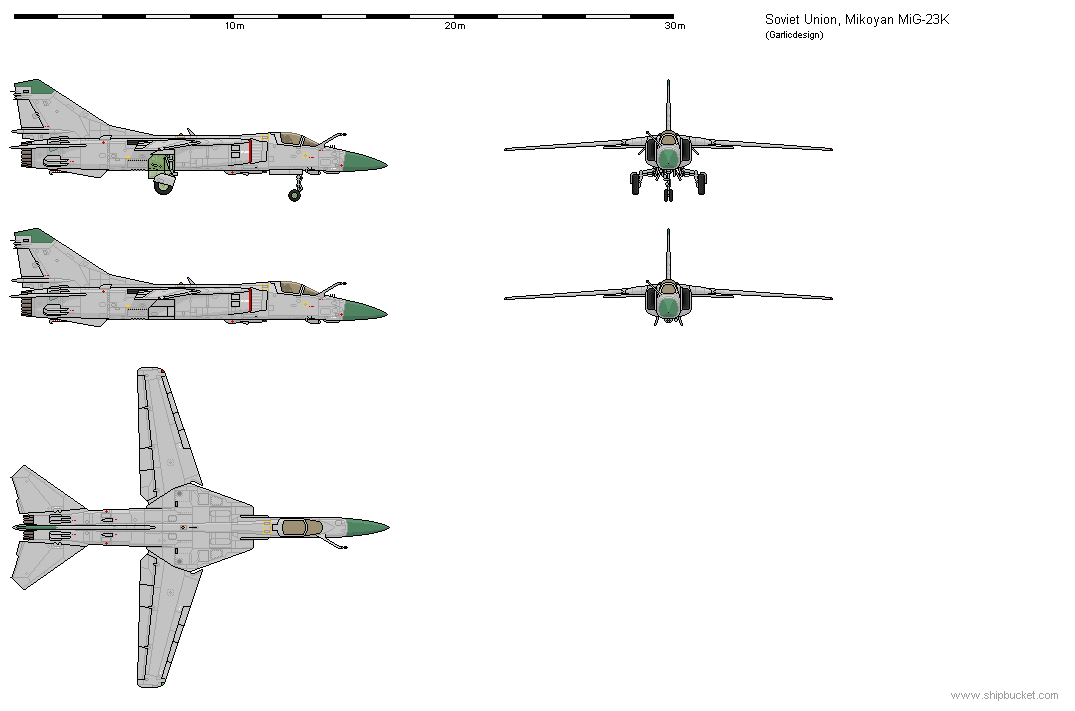

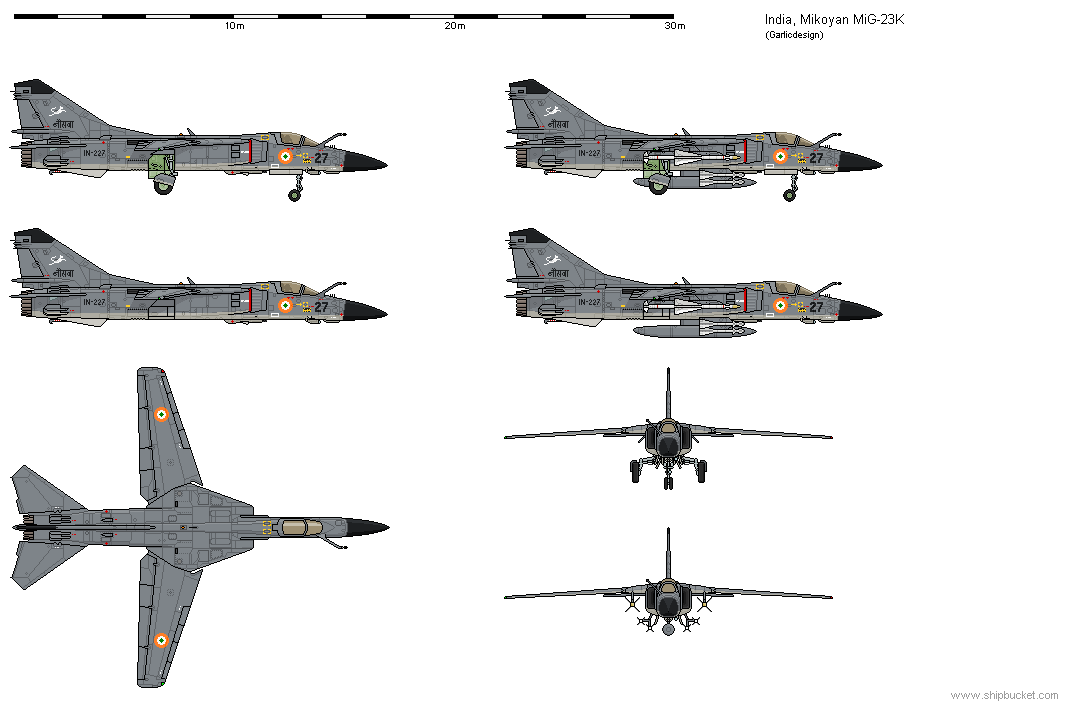

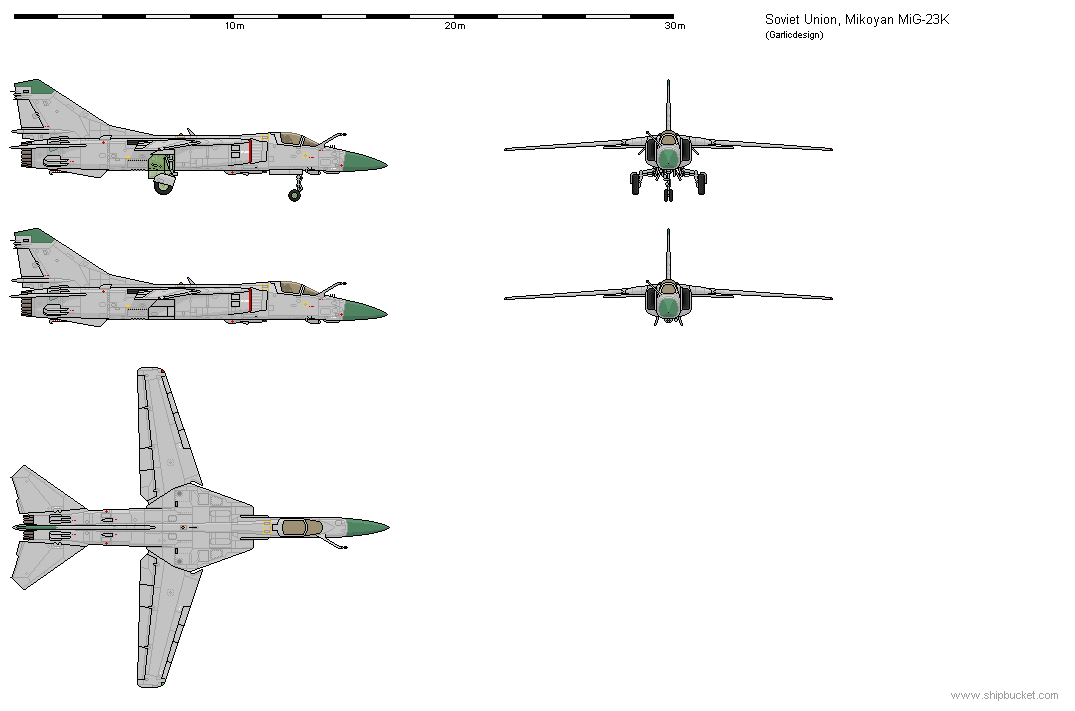

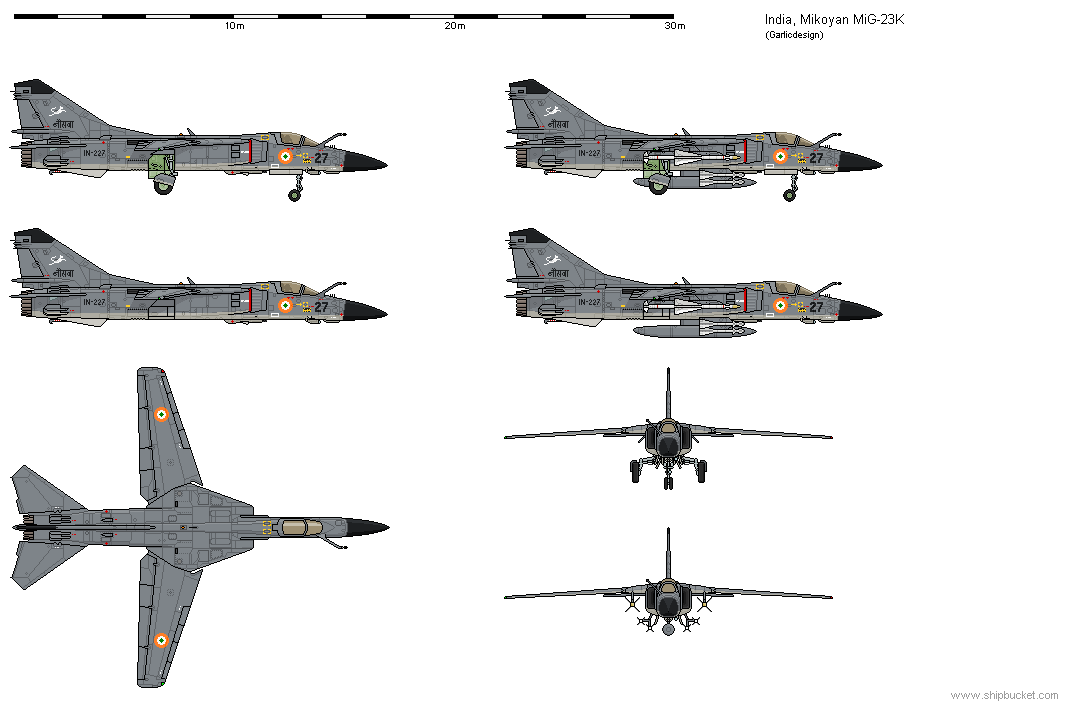

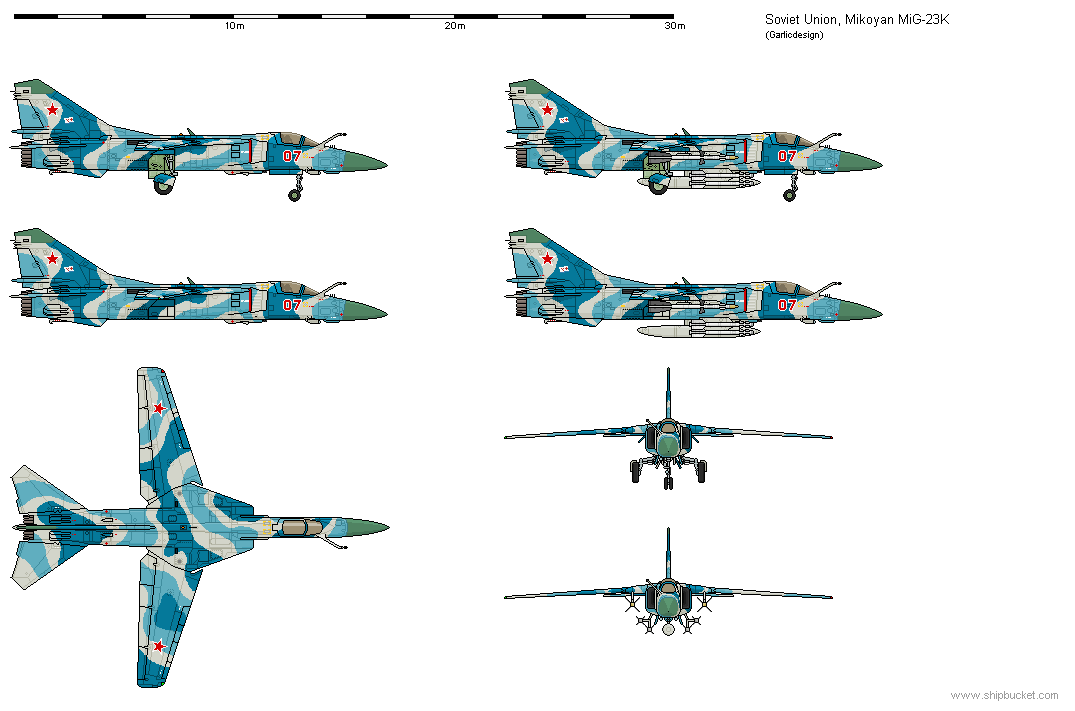

3.3. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23K ‘Flogger-M/N’

The Yak-33 had been built in limited numbers and suffered quite some attrition, mostly by accidents; when the Soviet carrier fleet was greatly expanded in the 1970s, more fighters were needed. This spelt an early demise for the Yak-33, because for standardization’s sake, the replacement had to be a variant of an air force fighter. This decree narrowed the choice pretty much down to the MiG-23; it was the only current Soviet Mach-2 fighter small enough for fitting into a carrier hangar, and the one with the best low-speed performance due to its variable geometry wings. To adapt the type for carrier service, considerable re-design was necessary – so considerable in fact that the resulting plane had only 30% of its parts in common with the land-based MiG-23. It received a completely re-worked bow with a raised cockpit for better visibility, slightly larger wings and a slightly stretched hull with 30% more fuel capacity, a larger horizontal stabilizer, two small, canted ventral fins instead of the single large foldable one, strengthened undercarriage with carrier fittings and arrestor hood, and a fixed aerial refueling probe. The prototype took to the air early in 1975.

As there never had been a competing design, the MiG-23K was commissioned straight from the drawing board. Testing and ironing out teething troubles took till 1978; series production was approved late that year. Deliveries started early in 1979, and the first squadron refitted from Yak-33 to MiG-23K in October. Like its air force pendant, the MiG-23K was not much of a dogfighter, but then neither had been the Yak-33. With its armament of up to four R-23 (AA-7) (or two of them and and four R-60 (AA-8)) missiles and its speed of Mach 2,35 – the strengthened naval version could attain Mach 2,5 in a dive – the MiG-23K was still a formidable enemy if properly employed (something the Syrians spectacularly failed to do with the land based variant in the 1982 Lebanon war). NATO reporting name was Flogger-M (out of sequence, the ‘M’ representing the maritime role).

By 1983, eight squadrons and two OCUs of ten planes each were equipped with a total of 155 MiG-23Ks; production for the AV-MF continued till 1986, by which time 290 machines (including 50 MiG-23KUB trainers) were delivered to equip ten shipborne squadrons (two on each Kiyev-class ship, one each on Moskva and Leningrad), five land-based squadrons and three OCUs. The trainer version was fully combat capable and called Flogger-N by NATO.

Apart from the fleet air defense role, the MiG-23K could be fitted with recce pods for photo reconnaissance.

For the MiG-23K, there was only a single export customer. The Indian Navy needed to re-equip two fighter squadrons of Super Scimitars by 1985 at the latest, and an order for 50 MiG-23Ks (including ten trainers) went out in 1984. They were delivered 1986/7; the last machine was the final MiG-23 ever built. Service on the small Indian carriers was as difficult and accident-prone for the MiG-23K as it had been for the Super Scimitar; nearly half of India’s MiG-23Ks were lost within ten years, prompting a repeat delivery of 20 airframes from Russian stocks in 1998. Nevertheless, they remained in service for twenty years and were replaced with MiG-29K from 2006.

Starting in 1990, the Soviet Mig-23Ks had been upgunned with R-27 (AA-11) and R-73 (AA-11) missiles.

Moskva was retired in 1993 when the new large carrier Vladivostok became available; her MiG-23Ks transferred to Vladivostok, and Leningrad reverted to the training role. Kronshtadt was de-commissioned that same year and scrapped in 1999. MiG-23K was ready to be retired as well; the carrier Ulyanovsk was commissioned in 1996 with an air group of MiG-29Ks and Yak-39s. Kiev and Minsk, freshly refurbished, were transferred to Lemuria in 1998 to obtain urgently needed funds and cut on personnel expenses for carrier crews after the Soviet Union’s breakup in 1996. The never modernized Novorossijsk followed her sisters to Lemuria in 2001 to provide spares. Although the MiG-29K was introduced slowly and in limited numbers (most of the early production was reserved for India and Lemuria, again to gain hard currency), the Russian carrier fleet was down to three operational units in 2000 (Ulyanovsk, Vladivostok and Arkhangelsk (ex-Baku)), there were enough MiG-29s and Yak-39MFs to equip them, and the MiG-23K was made redundant. They were de-commissioned between 1998 and 2002.

To be continued even more

GD

3. The 1970s

After Khrushchev’s removal in 1964, Soviet military doctrine changed back towards a focus on conventional forces, influenced by Admiral Gorshkov and Marshal Grechko. As the 1970s marked the apex of economic development in the Soviet Union, funds were now available for Gorshkov’s grand scheme to turn the Soviet Navy into a blue water force to rival the USN. Of several competing carrier designs ranging in size from 85.000 down to 52.000 tons, the nuclear powered powered 60.000-ton Project 1150 was chosen for construction in 1968. Although the only shipyard capable of building a carrier of such size was Nikolayev and passage of capital ships (battleships and aircraft carriers) through the Dardanelles was prohibited by international treaties, a proposal to mount a battery of twenty-four P-500 (SS-N-12) antiship missiles and call the whole vessel a cruiser was rejected by Gorshkov as a poorly concealed cheat. If you have to cheat, he argued, go big and bold. Better not to impair aircraft carrying facilities by blocking half the available hangar space with useless missiles and call the ship a heavy aviation cruiser (Tyazhelniy Avianesushchiye Kreiser) anyway. The final design utilized an island design similar to the larger Project 1160 and carried heavy defensive weaponry: four twin 76mm guns, eight 30mm CIWS, two twin M-11 (SA-N-3) air defence missile launchers and four twin Osa-M (SA-N-4) point-defense missile launchers. Three catapults were provided, and a practical air group of 40 – 60 machines (depending on size) could be embarked. Four hulls were constructed, one after another, at Nikolayev: Kiev (commissioned 1976), Minsk (commissioned 1979), Novorossijsk (commissioned 1983), and Baku (commissioned 1987). As completed, Minsk had 100mm singles instead of 76mm twins and a modified radar suite, and the last two eschewed the guns altogether. They also had completely re-designed islands and swapped the obsolescent M-11 SAMs with Buk-M (SA-N-7) systems. Old Kraznaya Zvezda was scrapped in 1975. Kronshtadt had been taken in hand to receive an angled deck in 1971 and re-entered service in 1974 as a training carrier.

3.1. Tupolev Tu-24/30 ‘Mace/Mirth’

Despite its obsolescence as a strike aircraft, the Tu-18 was a sound and sturdy design which had already been adapted as a makeshift antisubmarine patrol aircraft. The roomy hull was considered highly suitable for further development to a dedicated ASW platform, and since the ASW role had been added to the portfolio of the Soviet carrier fleet, Tupolev was asked to modify the Tu-91 accordingly. The result was a plane with the OKB designator Tu-145 whose prototype was presented in 1973. The bow-mounted turboprop was replaced with two Ivchenko AI-24s in the wings; at 2.850 shp each, total power was lower than Tu-91’s, as high speed was no longer a requirement. Top speed now was 575 km/h. Fixed gun armament was deleted. The bow was freed for a powerful surface search radar capable of picking up very small targets such as periscopes, or larger targets at very long ranges; without the shaft running straight through the cockpit, a third crewmember could be accommodated on the centerline, serving as a weapons and sensors operator. In the stern, a MAD probe was installed, and additional passive radar, thermal, wake-tracking and infrared sensors were added in the hull sides and on top of the tailfin. A sonobuoy launch battery was installed into the aft hull. Armament comprised depth charges, 400mm aerial torpedoes, single mounted 240mm and 325mm rockets, and Kh-23 (AS-7) missiles. The total package was a fully up-to-date ASW platform.

Series production was approved late in 1974, and the first production aircraft replaced the decrepit Tu-18 in 1976. The first squadron of nine embarked on Kiev in 1977, and the following Kiev-class carriers carried one squadron each from the beginning. More of the class equipped a dozen coastal antisubmarine squadrons, mostly deployed with the Baltic and the Black Sea fleets, but also to expeditionary units protecting Soviet naval bases abroad in Syria and Vietnam. NATO assigned the reporting name ‘Mace’.

All Tu-24s could be fitted with a buddy refueling drum, and were used in this capacity at least as frequently and intensely as in their primary ASW function. Production continued till 1983, and a total of 272 units of the basic ASW variant were built. They delivered sterling service for almost a quarter century. Most received a mid-life upgrade with totally revamped electronics and provisions for Kh-25 (AS-10) missiles.

The airframes were beginning to show signs of age since 1995, and replacement with the Beriev Be-36 – scheduled to begin in 1996 – was delayed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and was not completed before 2010.

By the time the Tu-24 was approaching operational status, acquisition of a carrierborne AEW platform was being given serious consideration. The Soviets at that time already had a rotodome mounted radar named Shmel – installed in the Tu-126 – but that one was large and heavy and could not be adequately miniaturized. On the other hand, a radar system similar to the one installed in the British Walrus (HS P.139B) for the Beriev Be-38 was under development. That two-part radar – code named Rasvet – was available for tests in 1978, when the Be-38 project was frozen when KGB found out the Beriev OKB to be infested with Thiarian spies. The Rasvet radar was the only part of the project not compromised, and it was decided to mount it in a modified Tu-24 as a stopgap measure. It soon became apparent it was not possible to mount it fore and aft in the Tu-24 because of structural limitations of the airframe. It could however be made to work if placed close to the centre of gravity, in a fashion similar to the vintage US EC-121, with one radome on top of the aircraft and the other one below. In this configuration, the first Tu-45 AEW variant took to the air in 1980. It received the service designator Tu-30. Tests showed the Rasvet radar was still far from mature, although the vertical arrangement worked better than the original horizontal one. It took two more years to get the Tu-30 operational, although the Rasvet was still a far cry from the contemporary US APS-125 performance-wise.

From 1983, a batch of 18 machines was delivered; by 1987, all four Russian frontline carriers embarked a flight of three. NATO called the type Mirth. The older Moskva and Leningrad were relegated to second line duties after 1985 and never received AEW platforms.

The Tu-30 and its Rasvet radar was plagued by persistent performance and reliability issues throughout its career; its value was more of a symbolic nature, particularly because NATO did not know how bad it really was. In the late 1980s, the Be-36/38 project, which was still considered state of the art, was revived, and the AEW version was given top priority. When Be-38 became available in 1994, the Tu-30 was retired in a hurry. 15 remaining airframes were sold to the Lemurian Navy, along with two Kiev-class carriers and a hundred new MiG-29Ks, in 1998.

The Lemurians had little fun with their Tu-30s, because when they were fully operational in 2000, their neighbours were fully informed about its performance, or rather the lack thereof. Poor relations with anyone capable of supplying a replacement forced the Lemurians to operate the Tu-30 for twenty years; the Be-38 was not cleared for export prior to 2010, and negotiations were terminated in 2013 in favour of purchasing the Chinese KJ-600. This machine became operational in 2015, and Lemuria was the launch export customer, receiving a dozen between 2018 and 2020. The Tu-30 was finally retired late in 2019.

3.2. Yakovlev Yak-39 ‘Fungus/Mushroom’

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Yakovlev built a series of unsuccessful VTOL designs, culminating in the Yak-38 of 1974. Their main problem was that the Navy, for which they were designed, did not want any, because they feared the CTOL carrier programme might be cut short in favour of less capable, but also less costly aviation cruisers embarking a dozen second-rate planes at best. In a rare instance of initiative, Yakovlev tried to salvage the design by converting it to a CTOL trainer aircraft to replace the Yak-31 UTI, with a single-seat light strike derivative for export as an afterthought. Both designs received the OKB designator Yak-120. The plane resembled the VTOL Yak-38, but had a shorter hull (no space for lift engines needed) and wider wings providing good low speed flight characteristics. Power was provided by two Ivchenko AI-25FR turbofans, a reheated version of the standard AI-25 which delivered 18.5 KN dry and had an afterburner for 27 KN wet thrust. At an empty weight of 4.700 kilograms, the Yak-120 had ample internal fuel stowage and four hard points each cleared for 800 kilograms payload; a twin 23mm autocannon was mounted beneath the belly. Flight tests in 1976 proved great agility and excellent low altitude characteristics, with a top speed of 1.200 kph (Mach 0.95); at altitude, the plane was transonic, capable of 1.400 kph (Mach 1.3). It was the first Soviet combat aircraft with fuel-efficient turbofan engines, and with full external payload, a radius of action of 800 km was attained, almost as much as the much larger Yak-34, whose payload was only 20% bigger. The Yak-120 had a navigation radar, FLIR, IRST and a combined internal laser rangefinder/designator; it could employ the full range of Soviet air-to-ground ordnance without having to use external targeting pods.

The trainer version had a longer nose, with the seats in a staggered arrangement to improve view from the aft seat; it was the first Soviet trainer with this feature. It lacked the internal cannon.

Although the AVMF had no real requirement, the Yak-120’s simplicity and compact size – an important factor for carrier aviation – made it an attractive choice. By substituting one Yak-34 squadron per carrier with two squadrons of the new plane, air group size of a Kiev-class ship could be increased to 65, at very little loss in capability per plane. Additionally, the Yak-34 was neither designed for nor very good at low altitude penetration missions; the smaller Yak-120 could fly low-low-low mission profiles and evade much of NATO’s defensive measures, which were tailor-made to counter high-altitude saturation strikes. Based on these considerations, the Yak-120 was commissioned as Yak-39 in 1977, and 150 machines (including 50 trainers) were ordered to supplement the Yak-34 and start replacing the Yak-31 UTI. Deliveries were processed in 1978 and 1979. When NATO became aware of the type, it received the less than flattering reporting name Fungus.

The planes were instantly popular, and a follow-on order of 150 – half of them trainers – was issued in 1979, to be delivered between 1980 and 1982. To remain in theme, the trainer version was assigned the NATO reporting name Mushroom.

The Soviet Union was no traditional exporter of carrierborne aircraft, but the Yak-39 attracted interest of the Indian Navy, which considered it an ideal choice for their relatively compact carriers. 75 strike-fighters and 15 trainers were ordered in 1980 and delivered in 1982 and 1983; they replaced the hopelessly outdated Sea Hawks still in use with the Indian fleet in the maritime strike role and were adapted to carry a variety of British-sourced ordnance in addition to Soviet supplied Air-to-Air and Air-to-Ground missiles.

Apart from the Indians, the Soviets had no allies or satellites with aircraft carriers; their traditional export customers considered the Yak-39 insufficiently flashy for the air-to-ground role, preferring the Su-20/22 and MiG-23BM. Yak-39’s concealability and ability to fly very slowly at very low altitudes was considered attractive to the Vietnamese, who considered the plane ideal for providing close support in jungle warfare. They ordered 80 machines (including 15 Yak-39UTI) in 1982, which were delivered in 1984/5.

The final export customer was Cuba, whose air force wanted the Yak-39 for the maritime strike role; their 1984 order for 50 machines (including 10 trainers) was processed in 1986.

Meanwhile the Soviets had found that Yak-39’s airframe offered growth potential for installation of a downgraded and –sized variant of the Sapfir radar; an experimental refit was tested in 1985 and considered successful. 90 airframes were fitted with a modified nose with a radar cone, re-locating the laser designator to the starboard side and the IRST on top of the nose. ECM and avionics were also upgraded. The refit project was launched in 1986 and continued through 1988, yielding the new designator Yak-39M. Most other Yak-39s (of the strike version, a total of 175 had been delivered) were phased out by 1990; 25 were delivered to Cuba to bolster that nation’s inventory that year.